Ann ShaferIt was a “I’ve been plucked from the chorus line” moment. Back in 2008, I went on a tastemaker’s tour of Brazil with a small group of curators from various American museums. It was at the invitation of the Brazilian government—they had been running these sorts of trips periodically (our guide told us he had recently hosted a group of Japanese architects). It was meant to expose us to some of their museums, galleries, foundations, and artists in hopes of future collaborations between the two countries. We were escorted on the tour by a government representative, a super nice man named Carlos. We started out in Rio de Janeiro, flew to Salvador, then ended up in São Paolo. It was an amazing trip and we saw great art.

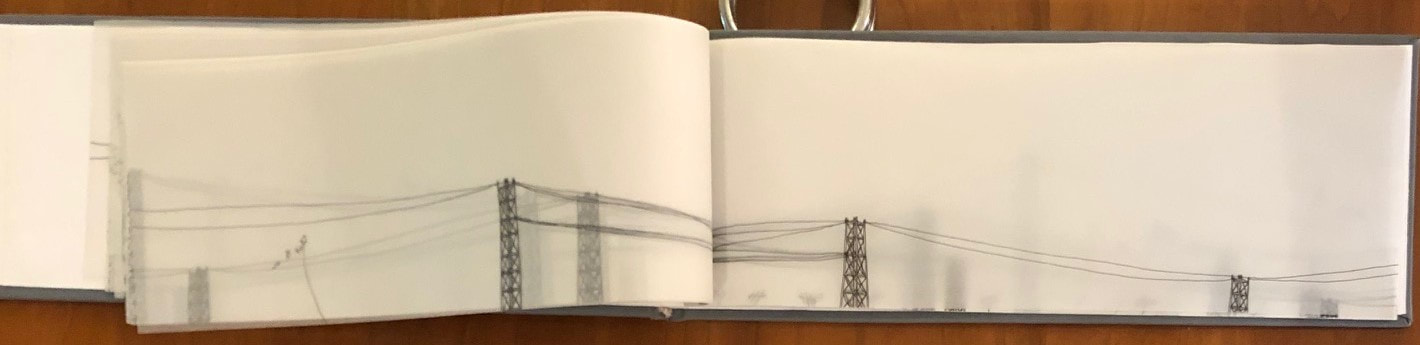

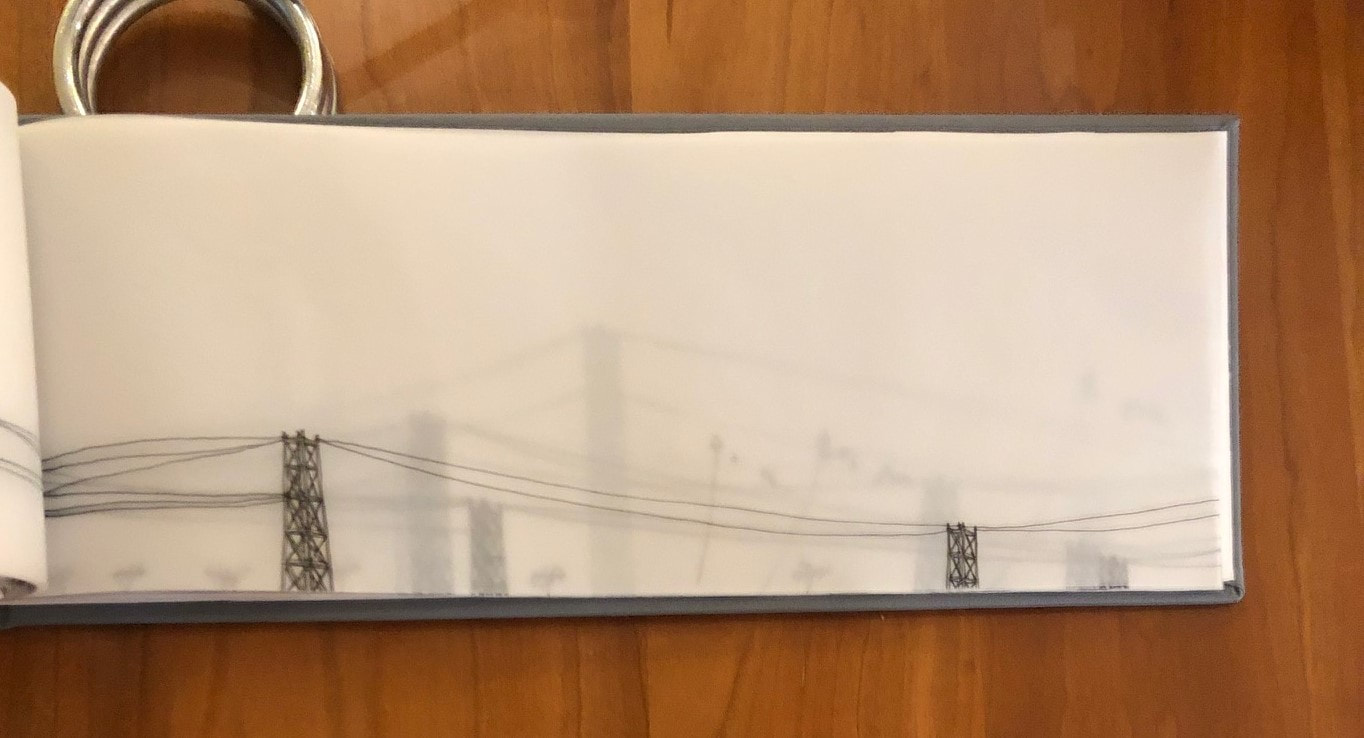

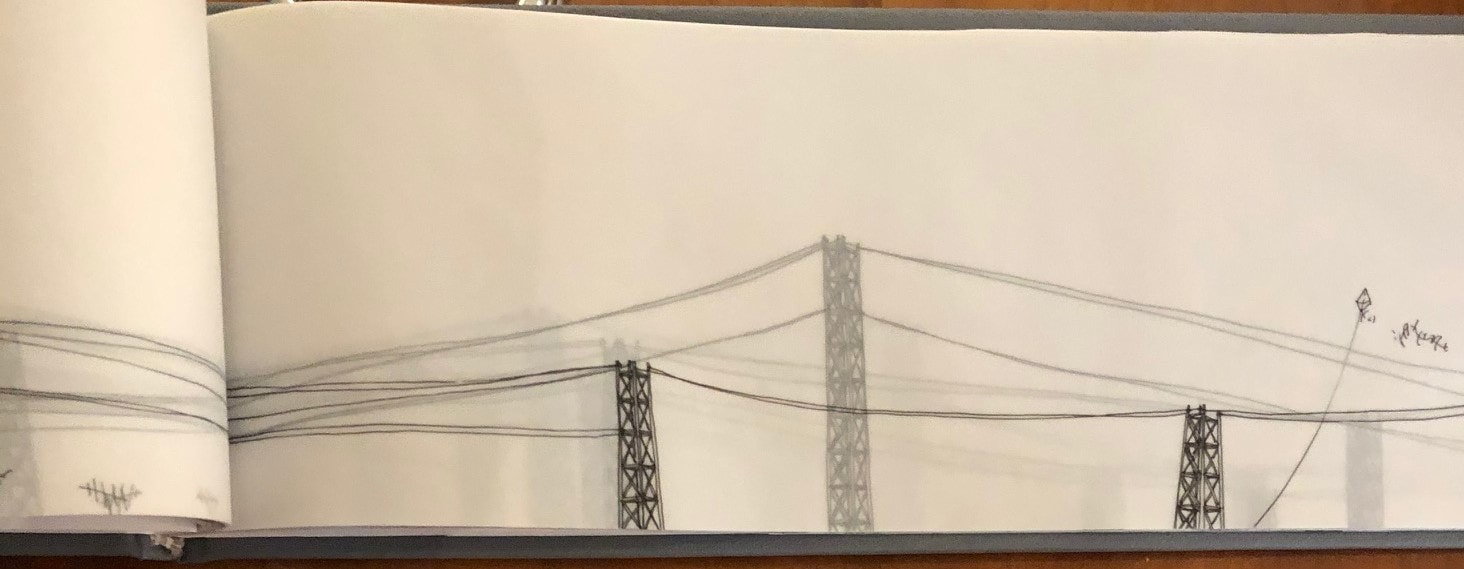

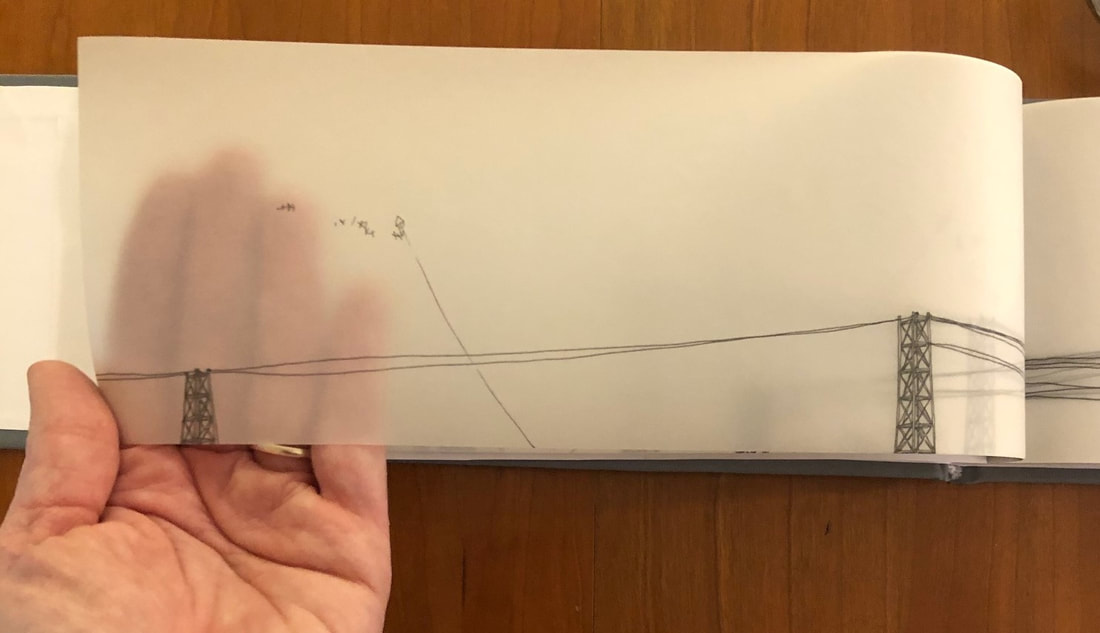

Along the way, I was introduced to a bunch of artists with whom I was unfamiliar. Some of my favorites are: Daniel Senise, Lina Kim, Alejandro Chaskielberg, Marcius Galan, Gerda Steiner & Jörg Lenzlinger, Marcello Grassmann, Oscar Niemeyer, Lygia Clark, Mira Schendel, Carlito Carvalhosa, Christian Cravo, Fayga Ostrower, Tarsila do Amaral, Nicola Costantino, Michael Wesley, Livio Abramo, Ernesto Neto, Lina Bo Bardi. When I returned to the BMA, I gave a presentation on all that we saw, which led to the only connection I was able to make. One of my colleagues, Karen Millbourne, fell in love with the work of Henrique Oliveira and included him in a show at her next museum of employment, the National Museum of African Art. He makes fantastical sculptures out of discarded plywood from urban construction sites (boards used in the fencing that blocks the view from the street) that take over spaces. São Paolo is a gigantic city that spreads out over 587 square miles. When you fly in, you see nothing but city as far as the eye can see. It just goes on and on. When we visited Galerie Vermelho, one of our last stops, I fell in love with an artist’s book by Kátia Fiera. It’s unique (there is only one of them--it is composed of drawings), and small, horizontally shaped and is filled with translucent sheets. Delicate line drawings in black marker of power lines, television antennas, and kites fill the textless pages. That you can see through each page to the subsequent pages, and that the power lines just keep going, beautifully captures the endlessness of the city, as well as its problems with pollution. While I didn’t know anything about Fiera at the time, I couldn’t pass up a perfect memento of a fabulous trip. Kátia Fiera (Brazilian, born 1976) De Passegem, 2007 Artist’s book Private collection Henrique Oliveira (Brazilian, born 1973) Desnatureza, 2011 Found plywood Galerie Vallois installation shot

0 Comments

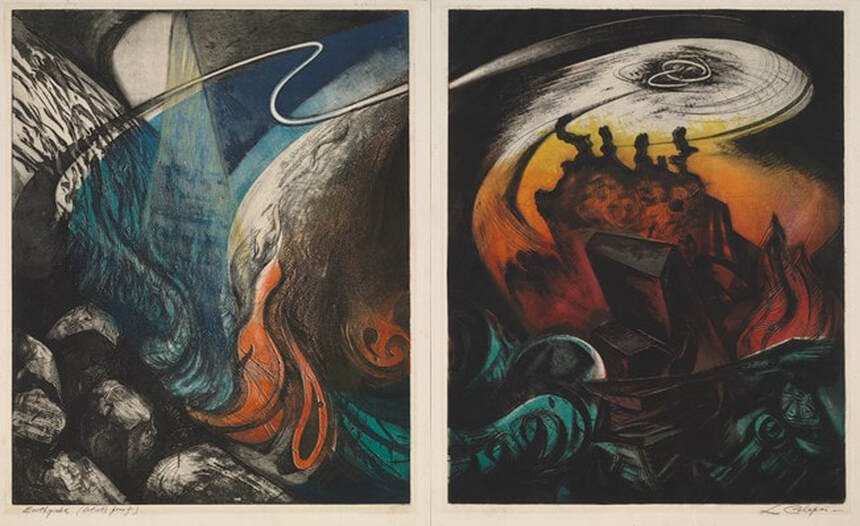

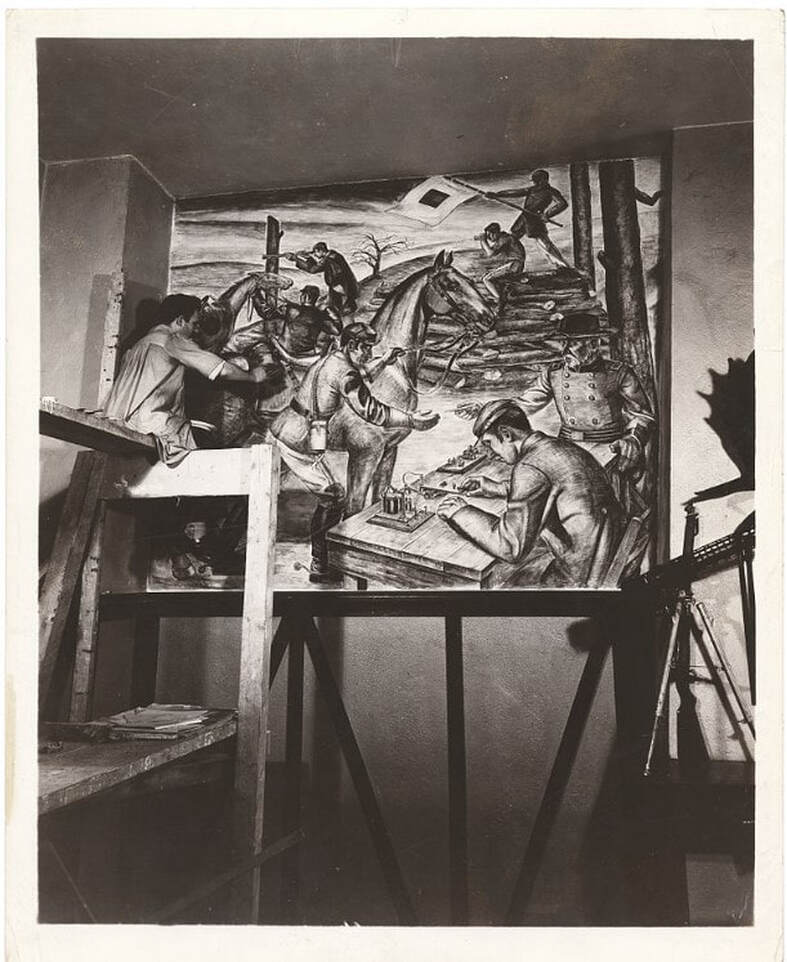

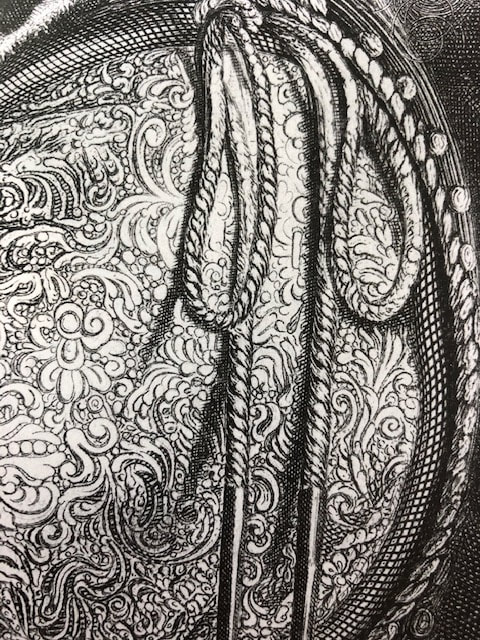

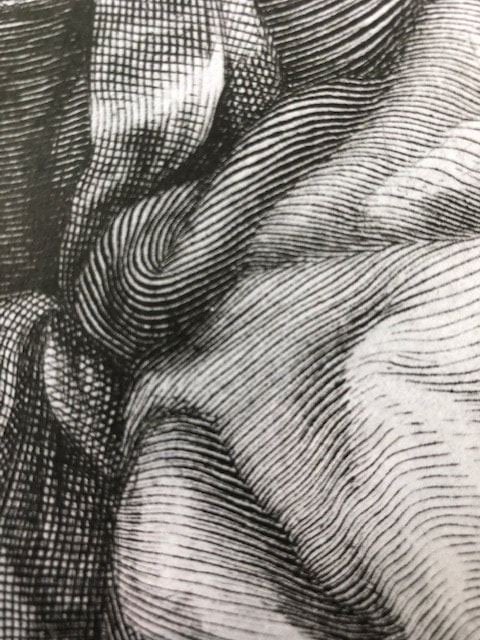

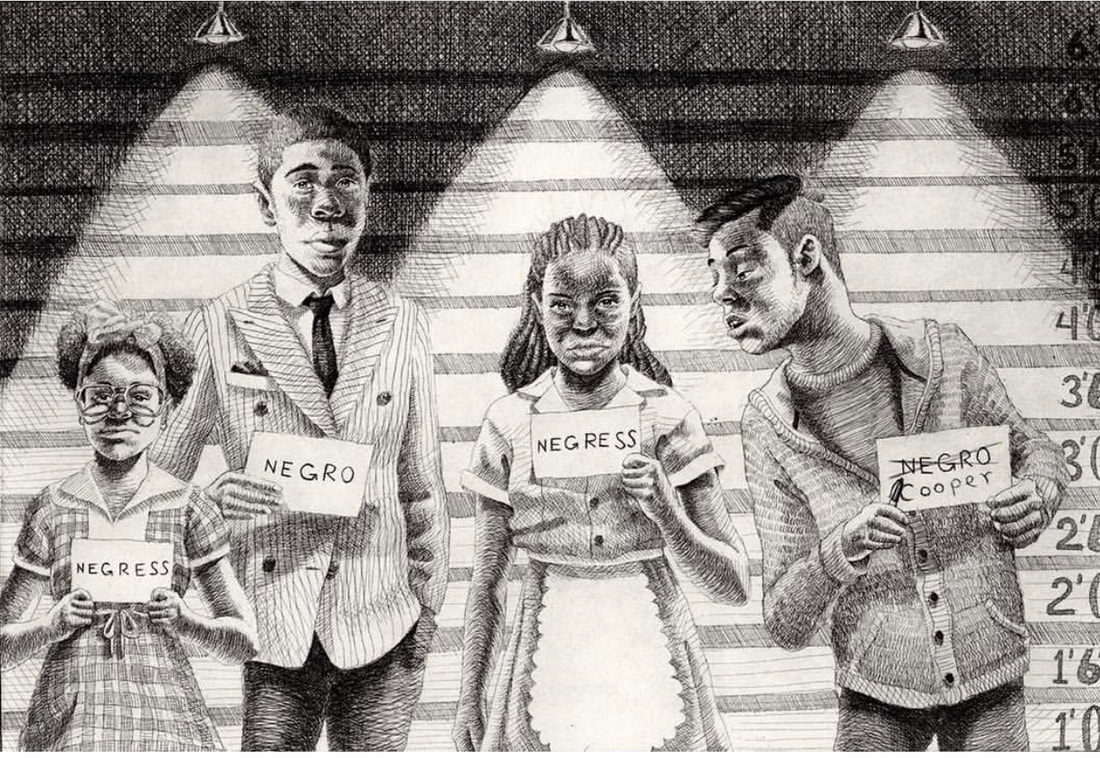

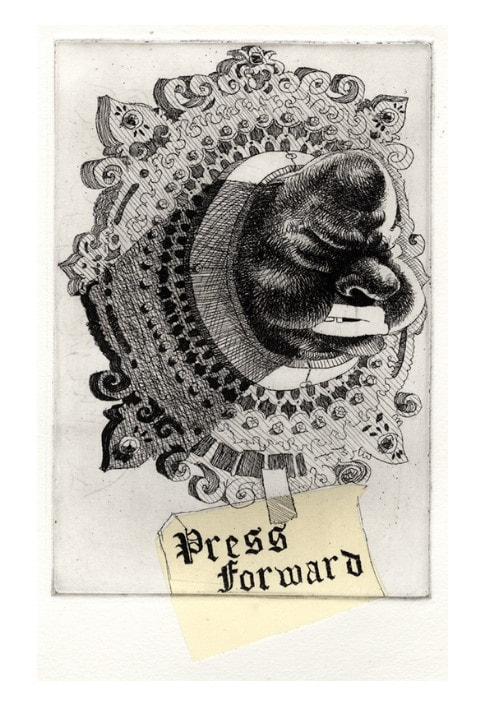

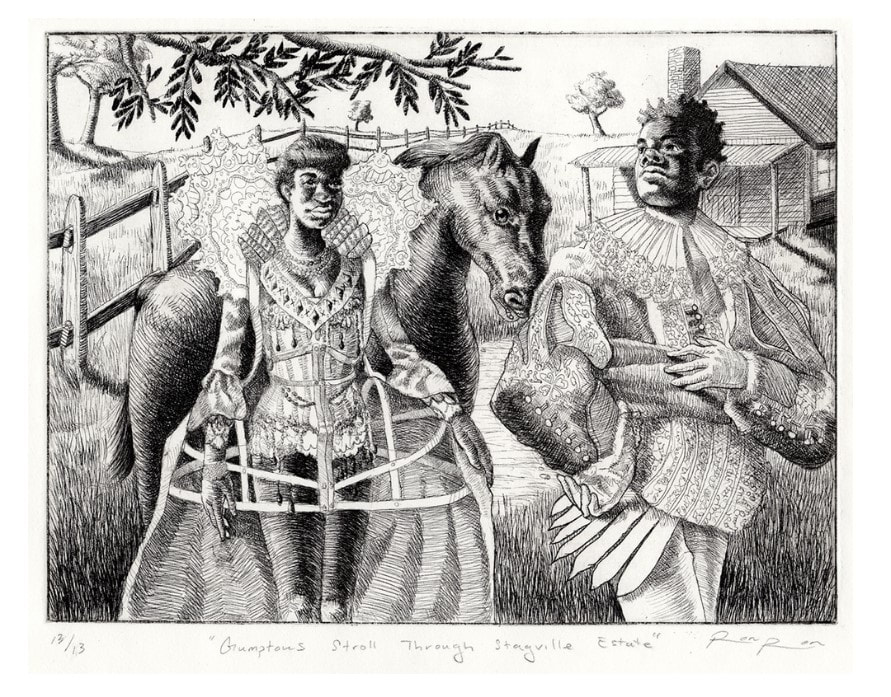

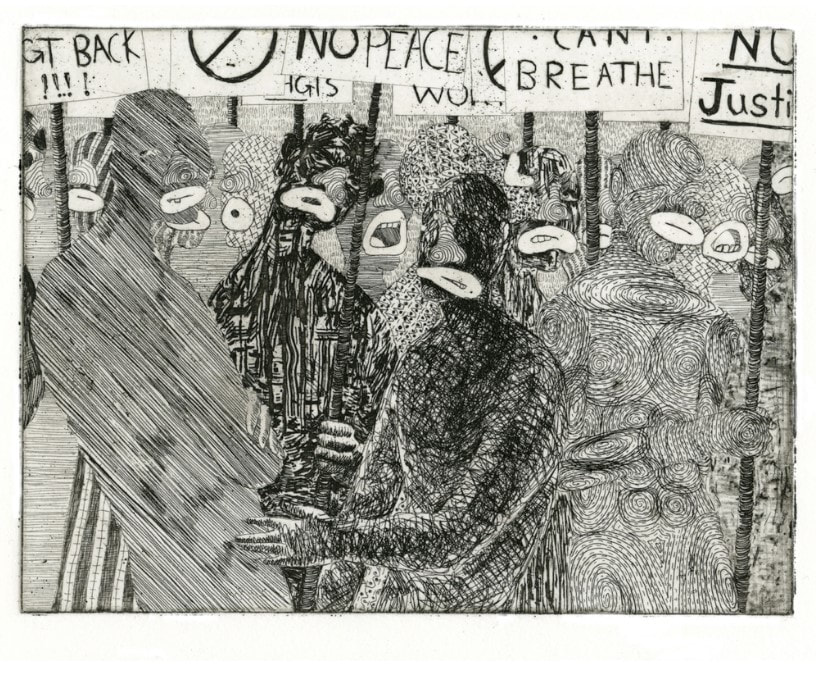

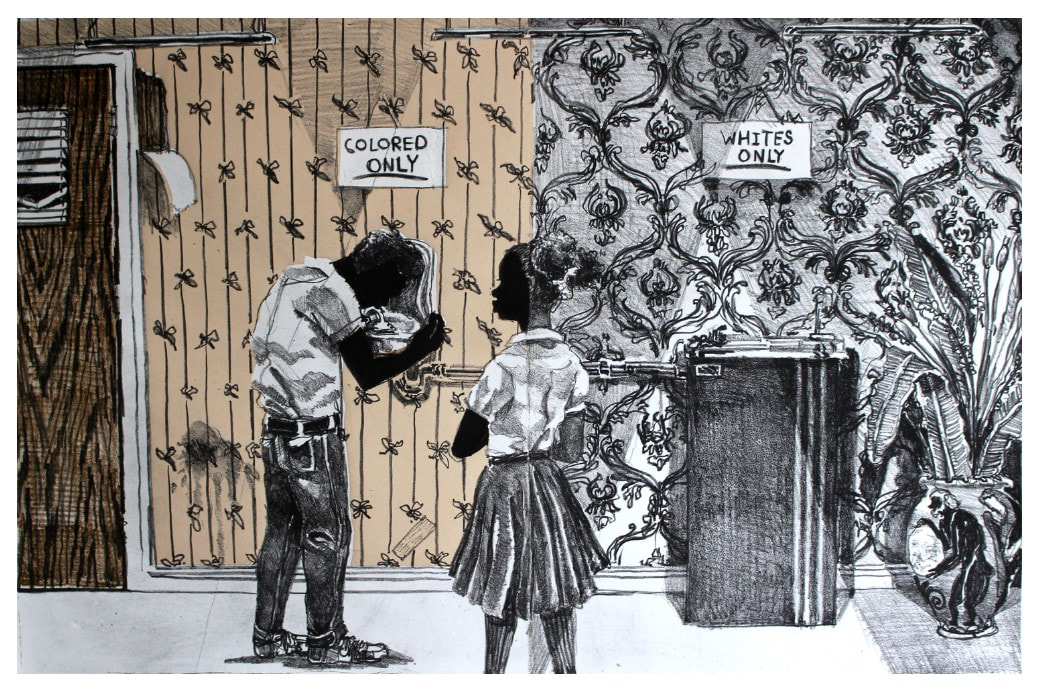

Ann ShaferHere’s a doozy for my simultaneous color printing friends. No surprise, Letterio Calapai worked with our man Hayter at Atelier 17 in New York in the 1940s. While Earthquake is from 1958, it is a glorious summation of techniques he learned among the many inventive artists frequenting Atelier 17. The print is really two prints that form a diptych. I've seen images of the two sides abutting each other, but the BMA would likely present these in a single frame, but with two windows in the mat with a center strip covering the seam. Letterio Calapai followed the path of many other American artists who worked at Hayter’s Atelier 17. After growing up in Boston, he moved to New York in 1928 and supported himself by working in a lithographic shop. He worked for the WPA early on painting a mural in the 101st Signal Battalion at 801 Dean Street in Brooklyn among other projects (see image). By the time Hayter moved Atelier 17 to New York from Paris in 1940 (fleeing German occupation), Calapai was continuing his artistic studies. It wasn’t until 1946 that Calapai worked at Atelier 17; he continued making prints there until 1949. His shift from 1930s realism to 1940s abstraction can be specifically linked to his time there. Like so many other artists who worked at the New York Atelier 17, Calapai went on to found a university printmaking program, in his case, the Graphic Arts Department at the Albright Art School in Buffalo (1949–55). He returned to New York to teach at the New School for Social Research from 1955–65. During his tenure at the New School, he established the Intaglio Workshop for Advanced Printmaking in 1962 (it ran until 1965). In 1965 he moved to Chicago and taught at, and retired from, the University of Illinois at Chicago. So, to the printing. Recently we’ve been pulling apart simultaneous color prints by Hayter. You can assume if Hayter did it, others did too, including Calapai. Earthquake is printed from two plates, which together are some 32 inches wide (big!). Both plates are inked in black (intaglio), where the ink is pushed into the lines and grooves of the plate. Rolled onto the surface (relief) are several colored inks added through screens (similar to a stencil): blue-green gradient, red, and green on the left, and green and red-yellow gradient on the right. The left plate also includes a yellow wood offset rolled through a stencil (similar to Hayter’s Sun Dancer, discussed in another post). For clarity, the description is broken down into bullet points to more easily list each component. Just remember, all of these colored inks are rolled onto each of these plates and are put through the press once. Letterio Calapai (American, 1902–1993) Earthquake, 1958 Diptych of etching, softground etching, open bite etching, and engraving

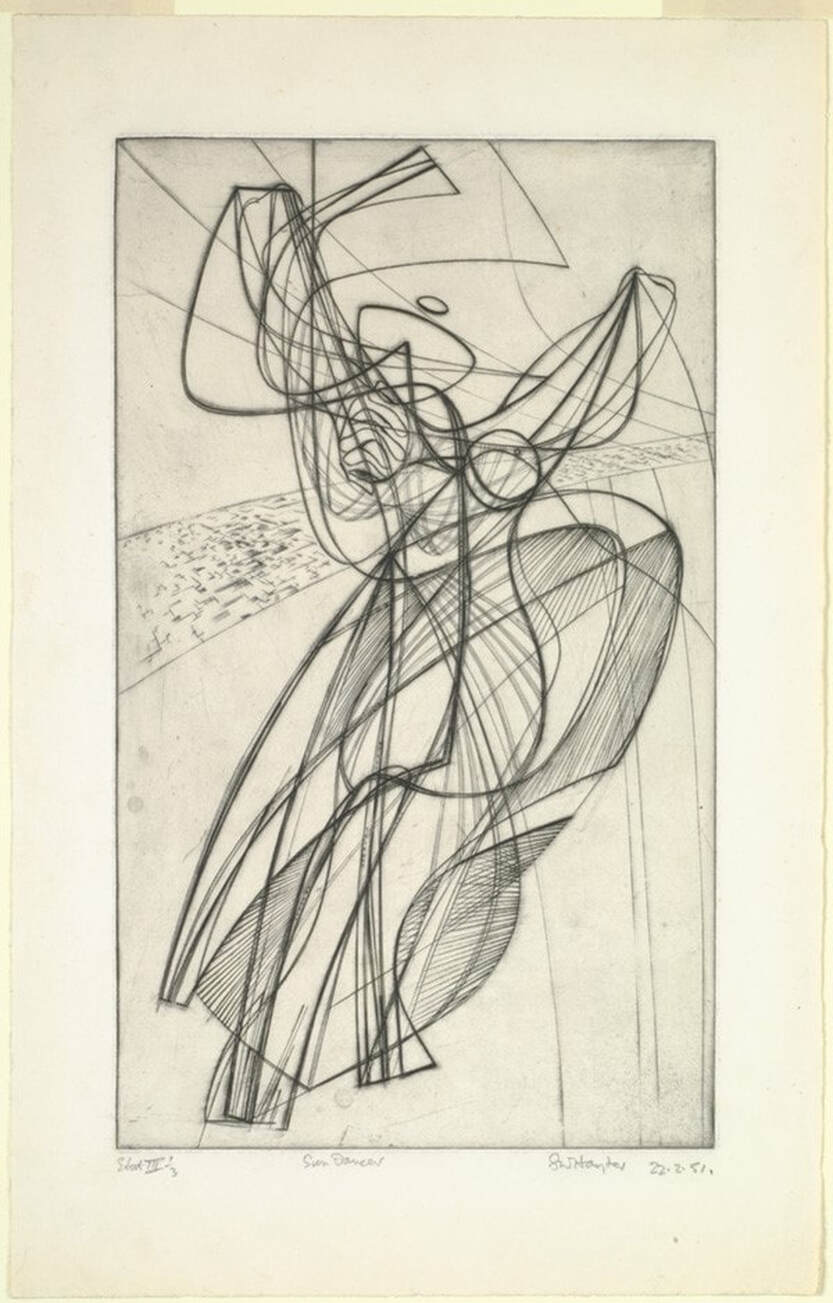

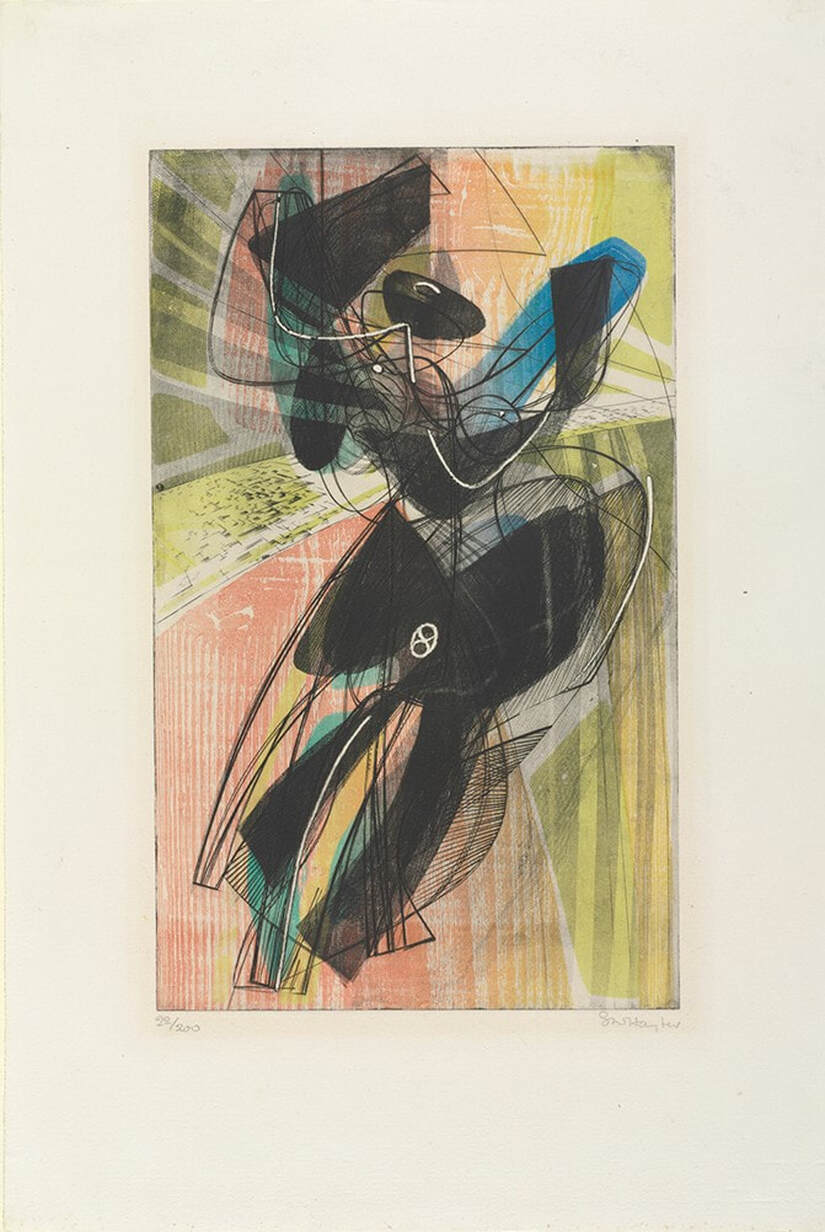

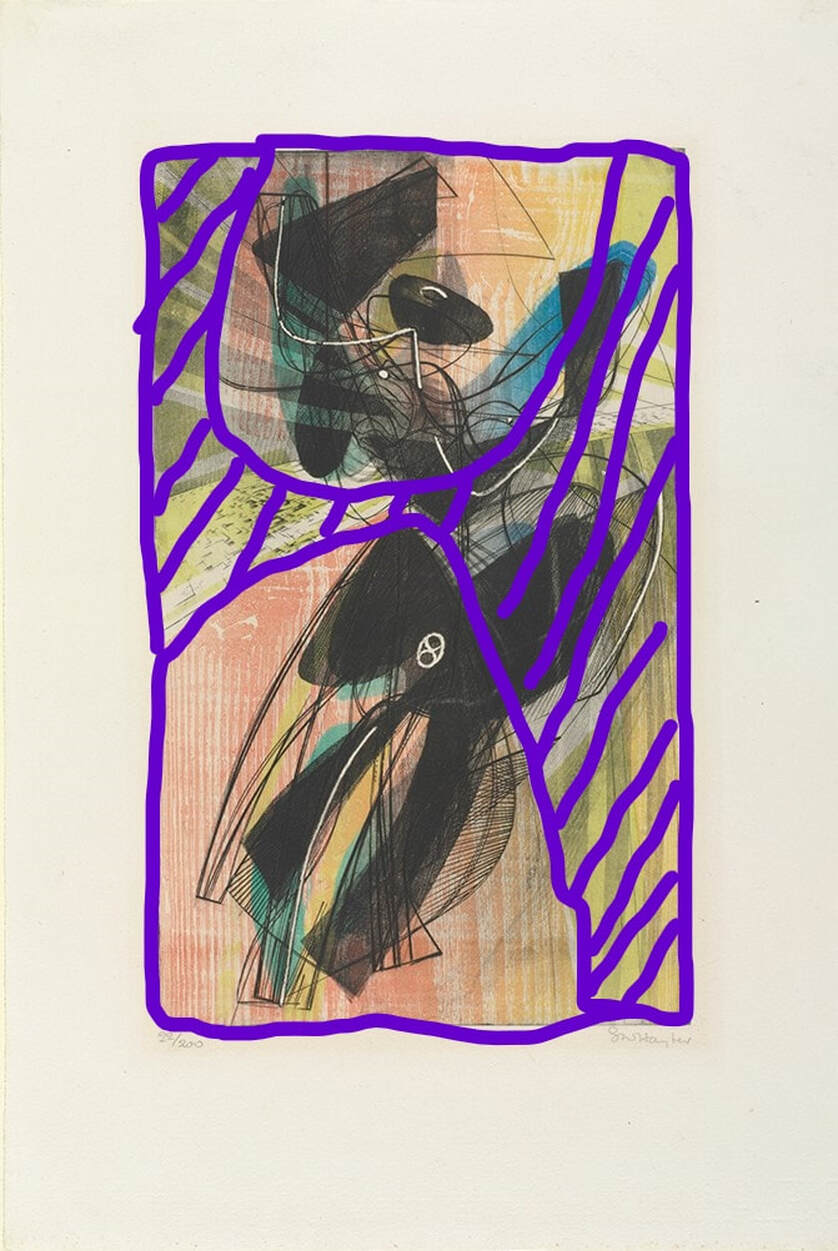

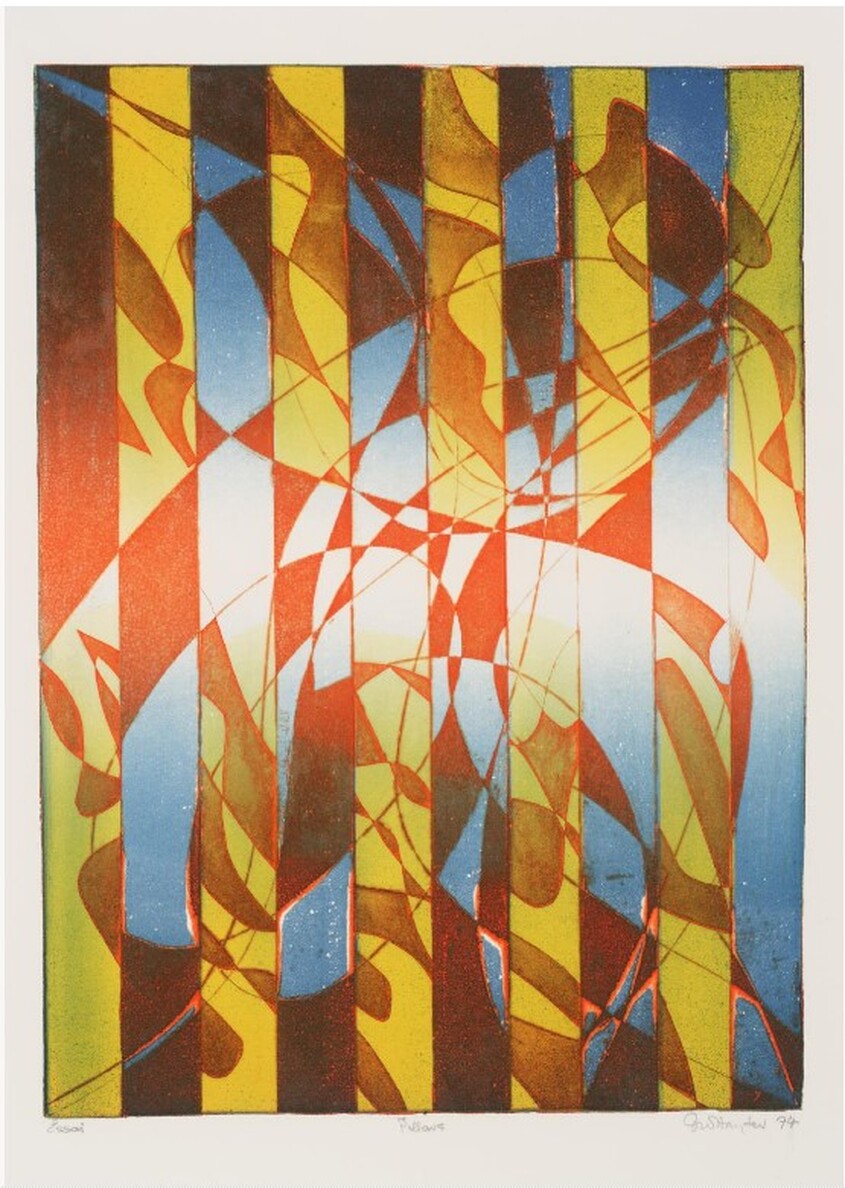

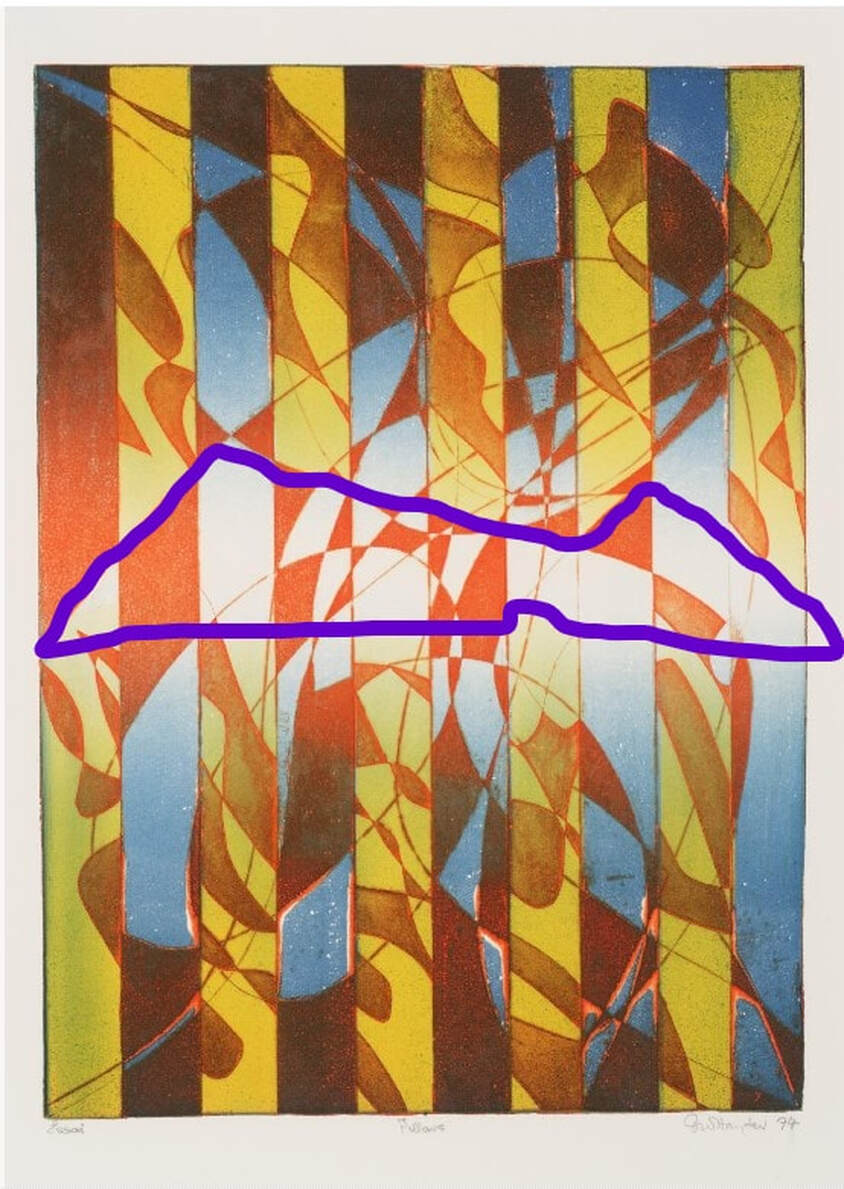

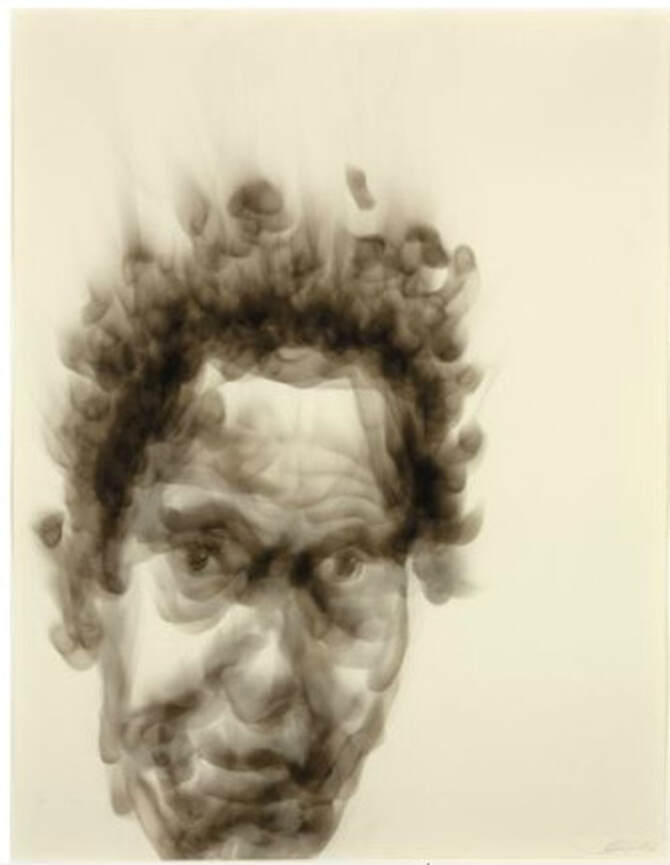

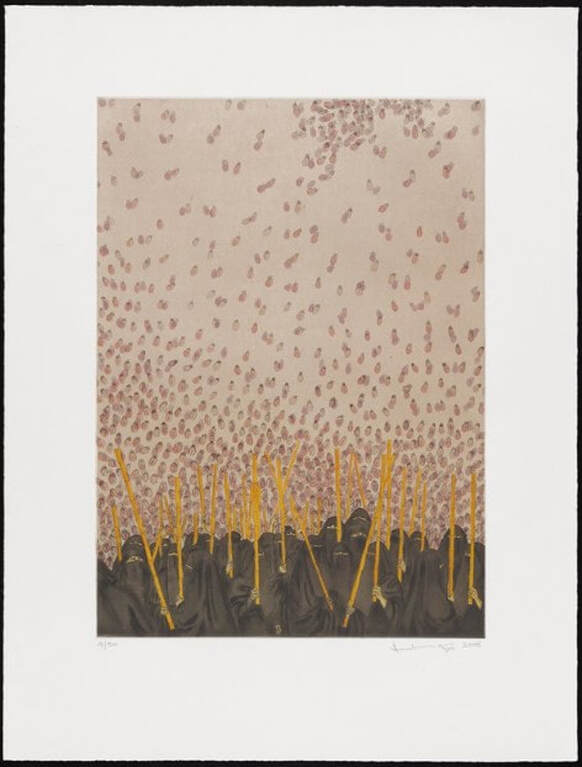

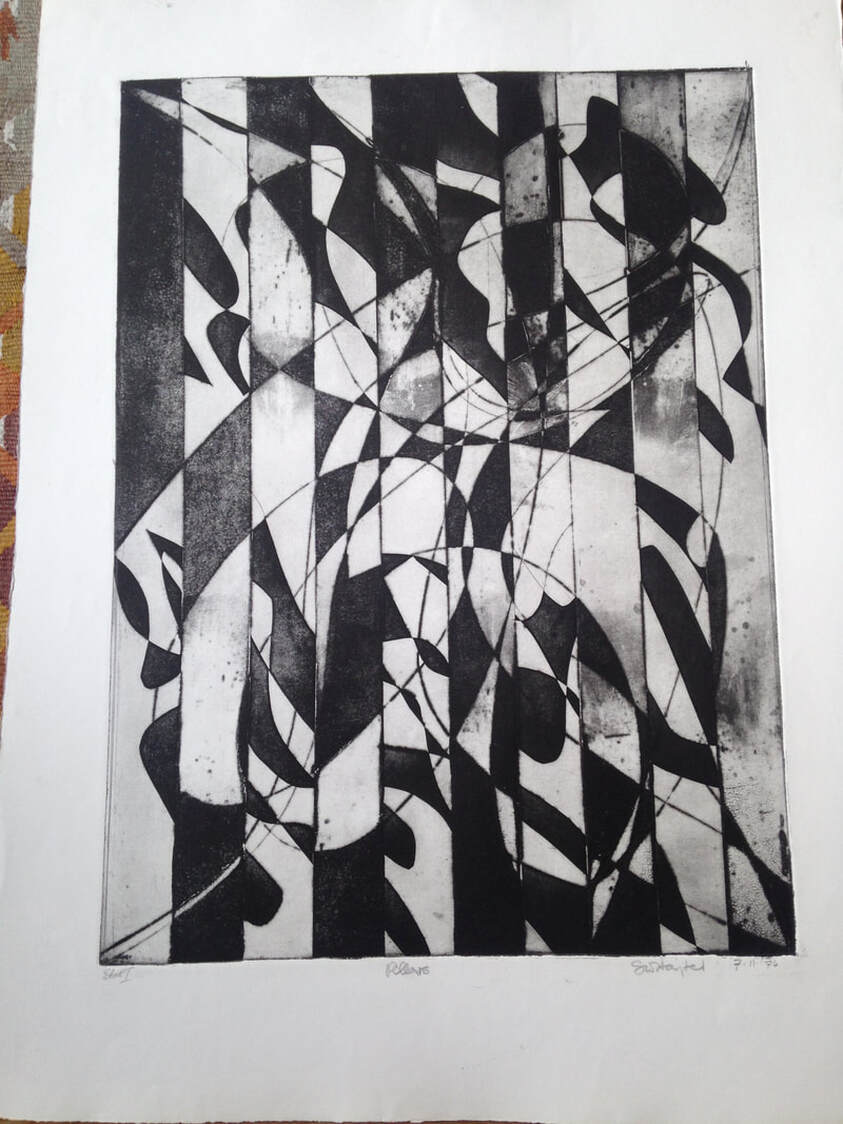

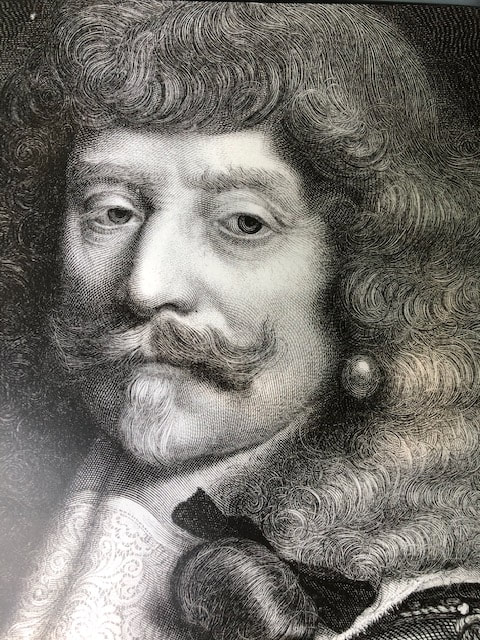

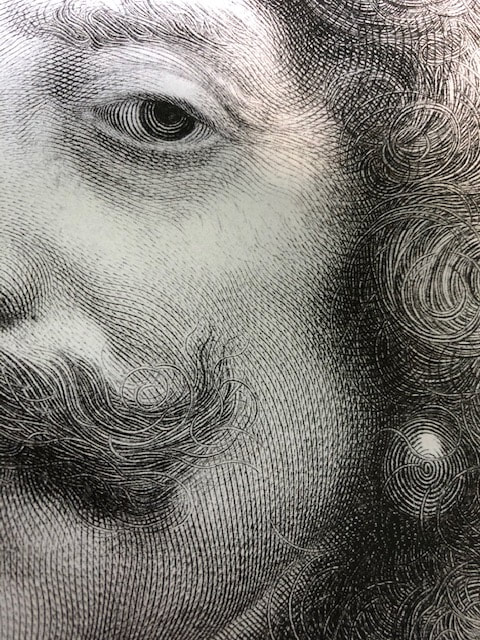

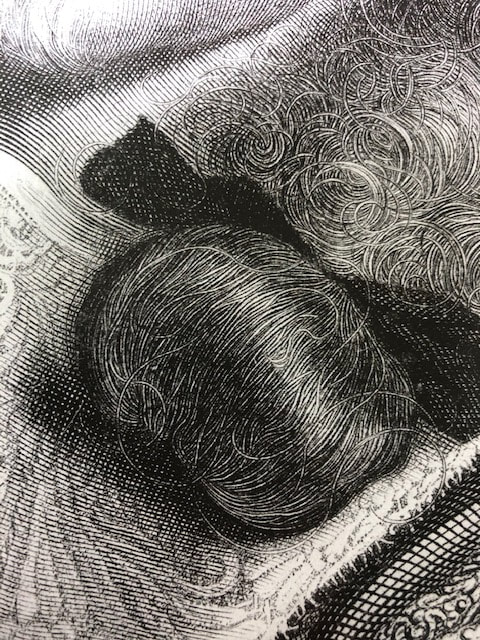

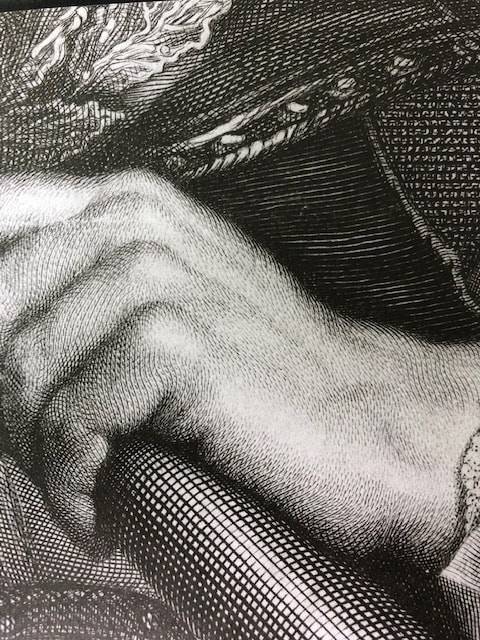

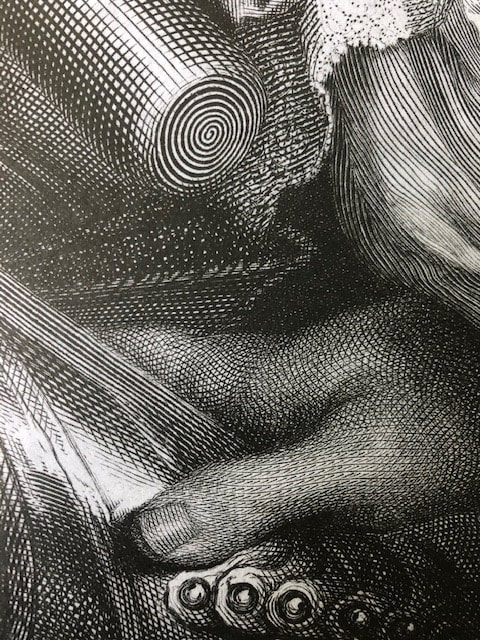

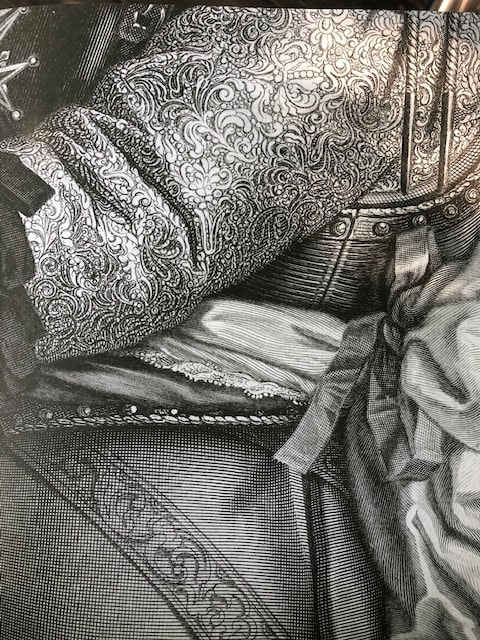

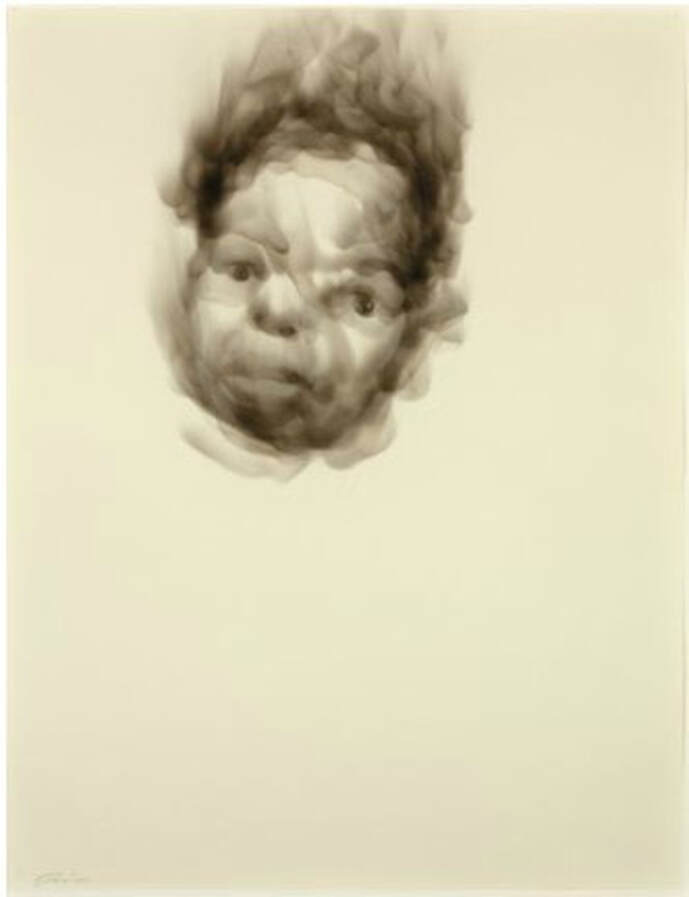

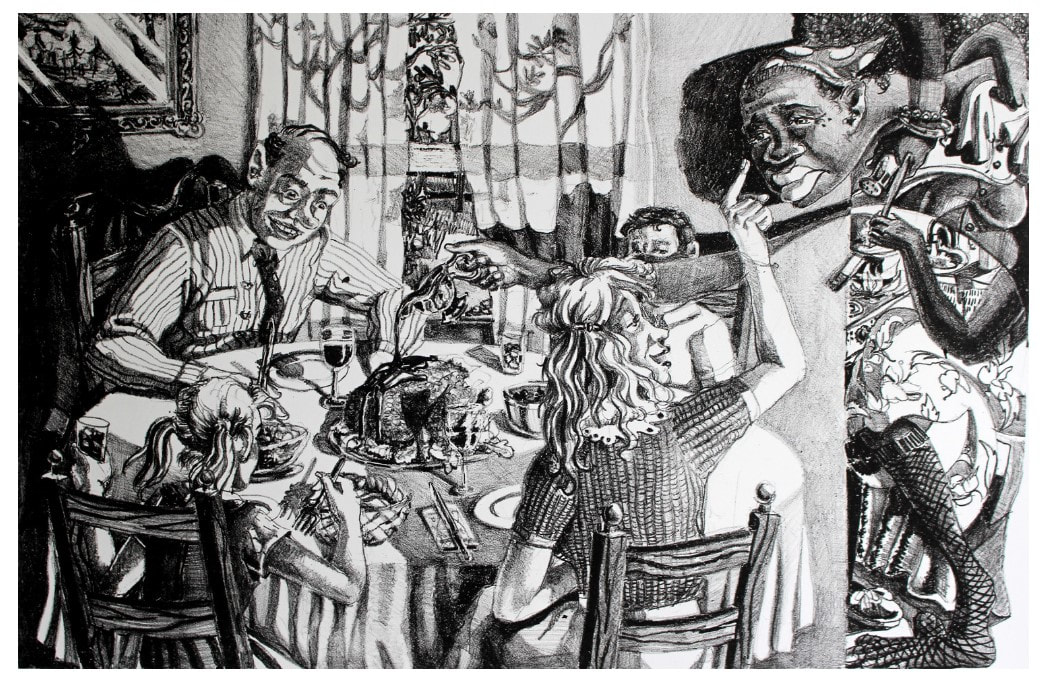

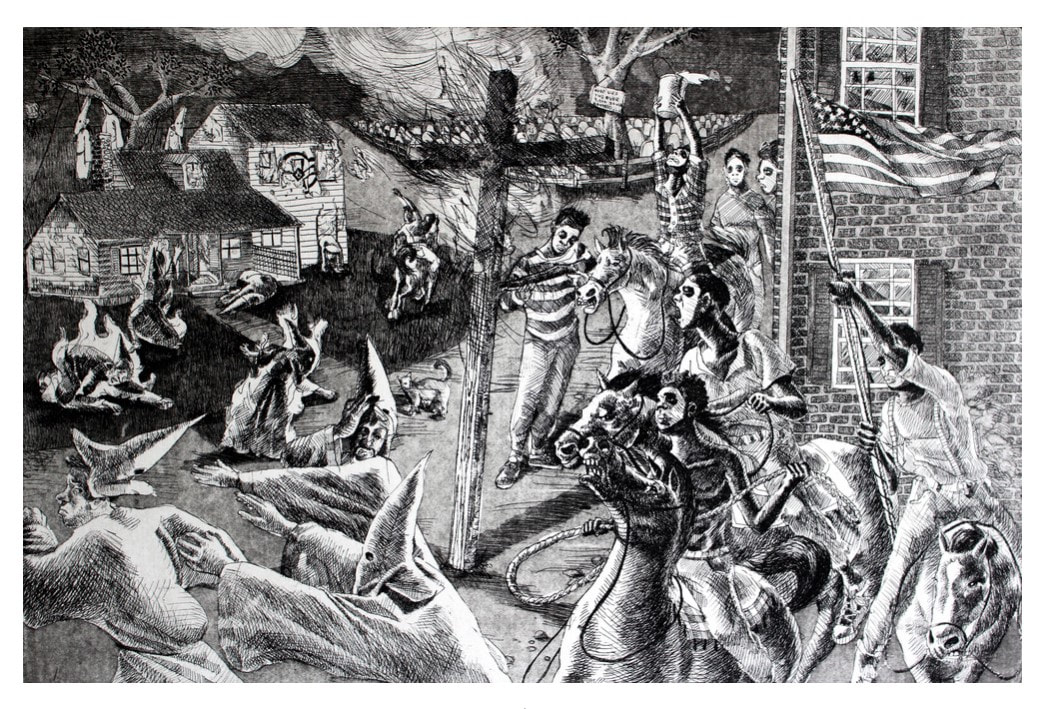

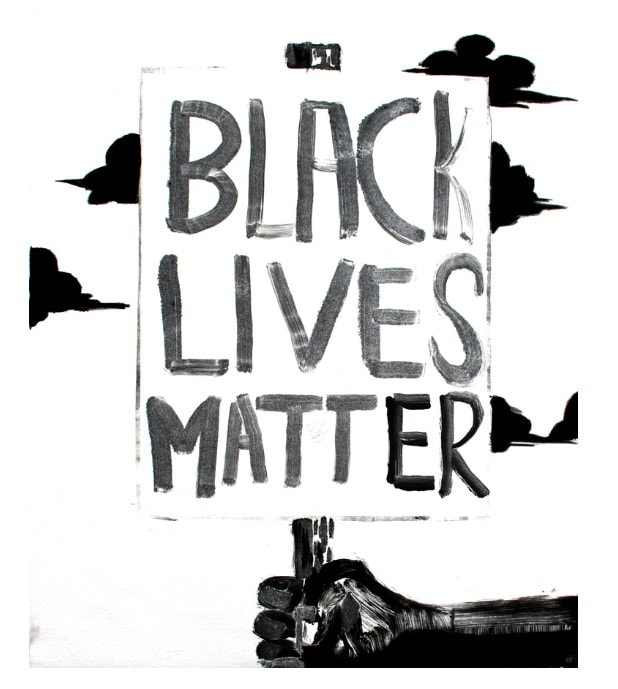

Sheet (right): 562 x 458 mm. (22 1/8 x 18 1/16 in.; plate (right): 504 x 404 mm. (19 13/16 x 15 7/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: The John Dorsey and Robert W. Armacost Acquisitions Endowment, BMA 2014.13a-b  Letterio Calapai (American, 1902–1993), Earthquake, 1958. Diptych of etching, softground etching, open bite etching, and engraving; left plate printed in black (intaglio), blue-green gradient (screen, relief) , red (screen, relief), green (screen, relief), yellow (wood offset, stencil, relief); right plate printed in black (intaglio), green (screen, relief), red-yellow gradient (screen, relief). Sheet (left): 562 x 432 mm. (22 1/8 x 17 in.); plate (left): 505 x 404 mm. (19 7/8 x 15 7/8 in.); sheet (right): 562 x 458 mm. (22 1/8 x 18 1/16 in.); plate (right): 504 x 404 mm. (19 13/16 x 15 7/8 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art: The John Dorsey and Robert W. Armacost Acquisitions Endowment, BMA 2014.13a-b Ann ShaferIn a previous post, we looked at the new system Ben Levy came up with to describe Hayter’s simultaneous color prints. We adopted a two-tiered method: the first line describes what is in the plate (the grooves and textures that carry the image); the subsequent lines describe each layer of inking, which are combined on the single plate and run through the press once. In our discussion we gave a few examples, and one included a wood-offset-stencil-relief roll. Sounds complicated, I know. I’m going to pull it apart for you. Hayter used the wood offset dealio in his 1951 print Danse de soleil (Sun Dancer). Published by Guilde Internationale de la Gravure, there were 200 in the edition (aside from any proofs or early states). Hayter had been experimenting with relief rolling colors of different viscosities onto the plate either through a silkscreen or a stencil for several years—his 1946 print Cinq personnages is considered his most important early use of this new-fangled printing method. By 1951, he’s on a roll (get it?). For Danse du soleil, Hayter used an offset pattern from a plank of wood. To get the texture and pattern of the wood to show up in a gradient of red-orange, he first rolled out the gradient on a glass palette, red on one end and orange on the other. (After a period of rolling, the inks merge in the middle and create a smooth mix of the colors.) Taking the roller with the red-orange ink, Hayter rolled the gradient onto a piece of wood that had just the pattern and texture he wanted. Then he took another, clean roller, one large enough that its circumference was equal to the height of the copper plate carrying the image, and rolled it across the inked-up wood once, picking up the exact image of the wood texture in the red-orange gradient. That roller was rolled across the surface of the already intaglio-inked copper plate once, depositing the image of the red-orange wood on the surface. He did this through a cut paper stencil so that the gradient only appears in certain areas. See the image where I added the purple marks indicating where the stencil allowed the gradient through. He also rolled on a yellow ink through a different stencil, as well as a blue-green gradient through another stencil. Neither of these two stenciled additions used an offset from another texture. Rather, the inks were rolled on a palette and directly rolled onto the plate through stencils. So, our description should now make sense: Engraving, softground etching, and scorper Printed in black (intaglio); red-orange gradient (wood offset, stencil, relief); yellow (stencil, relief); blue-green gradient (stencil, relief) Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988) Danse du soleil (Sun Dancer) [state 1], 1951 Engraving; printed in black (intaglio) Sheet: 503 x 317 mm. (19 13/16 x 12 1/2 in.) Plate: 397 x 233 mm. (15 5/8 x 9 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Paul Mann, Towson, Maryland, BMA 1979.362 Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988) Danse du soleil (Sun Dancer), 1951 Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio); red-orange gradient (wood offset, stencil, relief); yellow (stencil, relief); blue-green gradient (stencil, relief) Sheet: 566 x 379 mm. (22 5/16 x 14 15/16 in.) Plate: 394 x 238 mm. (15 1/2 x 9 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Blanche Adler Memorial Fund, BMA 1953.56  Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988), Danse du soleil (Sun Dancer) [state 1], 1951. Engraving; printed in black (intaglio), sheet: 503 x 317 mm. (19 13/16 x 12 1/2 in.); plate: 397 x 233 mm. (15 5/8 x 9 3/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Paul Mann, Towson, Maryland, BMA 1979.362.  Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988), Danse du soleil (Sun Dancer), 1951. Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio); red-orange gradient (wood offset, stencil, relief); yellow (stencil, relief); blue-green gradient (stencil, relief), sheet: 566 x 379 mm. (22 5/16 x 14 15/16 in.); plate: 394 x 238 mm. (15 1/2 x 9 3/8 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art: Blanche Adler Memorial Fund, BMA 1953.56.  Purple marks where the stencil lets the ink pass through. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988), Danse du soleil (Sun Dancer), 1951. Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio); red-orange gradient (wood offset, stencil); yellow (stencil); blue-green gradient (stencil), sheet: 566 x 379 mm. (22 5/16 x 14 15/16 in.); plate: 394 x 238 mm. (15 1/2 x 9 3/8 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art: Blanche Adler Memorial Fund, BMA 1953.56. Ann ShaferBack in June 2014, Tru Ludwig, Ben Levy, and I spent hours poring over prints by Hayter and associated artists of Atelier 17 with an eye toward technique. We wanted to change the way people describe these simultaneous-color-printed works so that it was clearer to the layperson how it was done. (They are confusing enough without adding fuzzy descriptions.) Ben devised a method for listing the mediums. We would first describe what techniques were used to make the image in the plate. Then we would follow with a description of how the plate was inked. In our Notes to the Reader (for the unpublished catalogue), we wrote about it this way: The most complicated aspect of the checklist is the media information. Conventionally, print media lines in checklists and on labels are concise, which assumes some knowledge on the part of the viewer. These works demand more explanation. To maintain consistency throughout in describing the techniques and media, we have adopted a two-tiered method of describing each print. For each entry in the checklist, readers will find the first line describes what is in the plate (the grooves and textures that carry the image). The subsequent lines describe each layer of inking, which are combined on the single plate and run through the press once. This second line also includes verbiage referring to the method of inking, which is divided into two categories: intaglio and relief. Intaglio inking means the ink is pushed into the grooves on the plate and the surface of the plate is wiped clean. Relief, in these cases, means that ink is applied to the surface using one of several methods: stencil, screen, various rollers. This last point is critical when discussing simultaneous color printing. Whereas traditional color printing requires a separate plate for each color, Atelier 17 artists discovered a method of printing in multiple colors on a single plate. A description of these terms and how they are used within the context of these complicated works is included below. Conventionally, for black-and-white prints, the media lines are pretty simple: Engraving and etching In this catalogue the same type of work is listed as: Engraving and etching Printed in black (intaglio) It gets more complicated when describing the works with multiple colors: Engraving and open bite etching Printed in black (intaglio), red (relief) Or even more complicated: Engraving, softground etching, and scorper Printed in black (intaglio), red-orange gradient (wood offset, stencil, relief), yellow (stencil, relief), and blue-green gradient (stencil, relief) Each layer of ink is described by the color followed by the method in parentheses. When multiple colors are listed in the same inking run, that means they were applied to the plate at the same time by the same means. Multiple colors connected by hyphens followed by the term gradient indicates several colors rolled and blended on a single glass palette (sometimes called a split fountain or rainbow roll). Multiple colors separated by commas followed by the term unblended indicates several colors that are unblended on the palette (think of mottled colors plopped on the palette). So, take Pillars, 1974. The orange ink is wiped in the intaglio manner, meaning into the lines and open-bit areas. This is followed by two rolls of ink across the surface in the relief manner, with varying amounts of oil so they reject each other. With these two gradient rolls, yellow and blue, Hayter (well, actually Hector Saunier printed this edition) also used a stencil to block the center area from the yellow roll and the blue roll (see the image with the purple shape representing the stencil—roughly). They also used gradient rolls for both the yellow and blue. Meaning, two columns of yellow at the outside portion were rolled with no ink in the center so that the yellow fades as it reached the center. The same was done with the blue. While this may sound like a lot of hogwash, I hope it clarifies a bit about the magical work going on at Atelier 17. In the first image, Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig are parsing Pillars, 1974, in June 2014, at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Pillars, 1974 Engraving, softground etching, and open bite etching; printed in orange (intaglio); blue-blue gradient (stencil, relief), and yellow-yellow gradient (stencil, relief) Sheet: 746 x 561 mm. (29 3/8 x 22 1/16 in.) Plate: 584 x 430 mm. (23 x 16 15/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Bequest of Virginia Fox, Palm Beach, Florida, BMA 1988.29 Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Pillars, 1974 Engraving, softground etching, and open bite etching; printed in orange (intaglio); blue-blue gradient (stencil, relief), and yellow-yellow gradient (stencil, relief) Plate: 584 x 430 mm. (23 x 16 15/16 in.) Tate Britain: Purchased 1981, P07471  Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig are parsing Pillars, 1974, in June 2014, at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988), Pillars, 1974. Engraving, softground etching, and open bite etching; printed in orange (intaglio); blue-blue gradient (stencil, relief), and yellow-yellow gradient (stencil, relief). Sheet: 746 x 561 mm. (29 3/8 x 22 1/16 in.); plate: 584 x 430 mm. (23 x 16 15/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art: Bequest of Virginia Fox, Palm Beach, Florida BMA 1988.29.  Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988), Pillars, 1974. Engraving, softground etching, and open bite etching; printed in orange (intaglio); blue-blue gradient (stencil, relief), and yellow-yellow gradient (stencil, relief). Plate: 584 x 430 mm. (23 x 16 15/16 in.). Tate Britain: Purchased 1981, P07471.  Stencil marked in purple. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988), Pillars, 1974. Engraving, softground etching, and open bite etching; printed in orange (intaglio); blue-blue gradient (stencil, relief), and yellow-yellow gradient (stencil, relief). Plate: 584 x 430 mm. (23 x 16 15/16 in.). Tate Britain: Purchased 1981, P07471. Ann ShaferOne of the reasons I love Stanley William Hayter so much is that I adore the quality of line he gets with engraving. In this method the artist uses a burin, a handheld tool with a diamond-shaped tip, to cut into the copper; they push the tool forward to incise a line in the copper into which the ink will lay. It takes a lot of strength and control, but it rewards the hard work. I love the swell and taper, the strength, the crispness. Hayter used engraving in a totally new way beginning in the 1930s. Prior to that the technique was used to reproduce the compositions of other artists. This type of print is known as a reproductive print. By these prints, the artist of the original composition could spread his designs far and wide, and the engraver could make a living. They were created by very talented engravers who devised a series of patterns of marks meant to mimic brushstrokes, fabric, hair, feathers, all the while in black and white. You can imagine that the advent of photography in the late 1830s killed this entire industry and engraving along with it. One hundred years later, Hayter revitalized the technique, but in a wholly new way. Reproductive prints are the bastard stepchild of the already bastard stepchild of prints, making them the bottom of the barrel. They don't get a lot of respect, but there has been a growing interest in them in the last few decades. Maybe they will soon have their day in the spotlight. I used to skim past these kinds of prints when going through solander boxes in the storeroom. They tended to be portrait after portrait of persons I didn't recognize or care about. They seemed trite, fussy, controlled, old fashioned, and are markedly different from the modernist prints of Hayter and the associated artists at Atelier 17. But as happens with prints, the more you slow down your looking, the more you see. As we used to say in the print room: "these reward scrutiny." I had a chance today to paw through Tru Ludwig's copy of Anthony Griffith's monumental book, The Print Before Photography (EDIT: not Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques, as first reported). The book is impressive, and the images are drawn solely from the collection of the British Museum. Its endpapers are a detail of a reproductive engraving by Antoine Masson of a portrait of Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt, by Nicolas Mignard from 1667. In the first few pages are more details plus the entire image. As you look through these details, check out how many different patterns are used and what they describe. This is when reproductive engravings get interesting for me: imagining an artist looking at a painting, or, more likely, a drawing of the painting, and attempting to render the flesh of the sitter's hand with black lines and dashes. Or the curling hair of his mustache. Or the shine of his satin sleeves. The list goes on. It truly boggles the mind. Antoine Masson (French, 1636–1700), after Nicolas Mignard (French, 1606–1668) Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt, 1667 Engraving Plate (trimmed within platemark) 544 x 390 (20 1/2 x 16 in.) British Museum: Bequest of Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode, R,6.209 Ann ShaferIf I am doing my job correctly, I rarely come across someone or something I’ve not seen before that I know is right for the collection immediately. Even better is when the work is a powerful statement protesting the justice system. Being in New York for Print Week means reserving enough time to scoot down to the galleries in Chelsea to see what’s up. We always go to the International Print Center New York to see what magic Judy Hecker has up. Then we wander down the halls at 526 West 26th Street to see Old Master dealer C.G. Boerner’s contemporary offerings as well as the projects on view in David Krut’s gallery. Back in 2010, Ben Levy and I made the rounds and discovered the superb work of South African artist Diane Victor at David Krut’s project space. The longest wall was salon-hung with Victor’s delicate and beautiful smoke drawings of black African men and children in which disembodied heads float on a white ground. You can’t help but be drawn in to investigate them more closely. We came to learn the drawings of adult males reflected men who were in prison awaiting trial, in other words, stuck in limbo. The children depicted were faces of those who were missing (Americans of a certain vintage will remember the missing children notices on our milk cartons). In both cases, they are people lost in the system. Victor draws with smoke emanating from a lit candle. (A short video of this process is here: https://youtu.be/-6E-BilDHkg.) Not only are the wispy marks ephemeral in a symbolic sense—these men and children have disappeared into the system—but also, they are literally ephemeral. The slightest touch to the surface will mar it irreparably. This delicacy reflects the precariousness of the situations these people find themselves in. The drawings are a great example of technique and meaning running in a tight conceptual circle. Even the titles, in which neither the man nor the child are named, adds to the sense of their loss—they are just numbers in the system. Standing in David Krut’s space, several things became clear very quickly. The first being that Diane Victor is a very generous person. The drawings were very reasonable, meaning they were entirely accessible to institutions and young collectors. This indicated, to me anyway, that the artist felt these conversation starters needed to be spread far and wide. Second, as a result, red dots were being placed next to drawings as we stood there. They were selling fast. Now, acquisition choices are not arrived at in a vacuum; I needed the okay to place a drawing on reserve. The problem was the person who needed to see these powerful drawings and agree with me couldn’t come until the following day. I was truly worried they would all be gone. It all worked out in the end—we were able to acquire two drawings—but there were some tense moments there. The website for The Artists’ Press (artprintsa.com) offers this description of the artist: “Diane Victor is somewhat like a spring, tightly coiled, tiny, and capable of great power…. She prefers imagery to words and the strength of her visual eloquence hits one in the gut and takes one's breath away.” The use of the term tightly coiled spring makes me smile because that is exactly how the writer Anaïs Nin described Stanley William Hayter: “a stretched bow or a coiled spring every minute, witty, swift, ebullient, sarcastic.” It seems both these high-energy artists are passionate about their message, craft, and sharing their talent with the world. My kind of artist. Like Hayter, Victor is also a prolific printmaker, working mainly in etching. I truly regret not acquiring several prints for the museum, but alas, it was not meant to be. I am, however, always keeping an eye out for what she does next. Instagram, on which one can follow so many artists and printshops directly, reveals that Victor has been at Island Press, part of the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, working on a gorgeous, large-scale etching called Beware the Lap of Luxury. Island Press posted several images of Victor working on the plate that will thrill fans of printmaking and which I include in this post (thank you, Lisa Bulawsky, Director of Island Press, for the images). It’s a beauty and I can’t wait to see it in person, although when that might be remains a mystery since the fall New York print fairs have been cancelled. So many of us are crushed to not be able to see everyone in person, from galleries and publishers to artists and museum colleagues. It truly is a printmaking Shangri-La, which will be all the more special when it returns. Diane Victor (South African, born 1964) Smoke Screen 7 (Frailty and Failing), 2010 Smoke carbon from candle over graphite Sheet: 660 x 508 mm. (26 x 20 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased in Honor of Rosalind Kronthal's Seventieth Birthday with funds contributed by her Family and Friends, BMA 2011.34 Diane Victor (South African, born 1964) Smoke Screen 9 (Frailty and Failing), 2010 Smoke carbon from candle over graphite Sheet: 660 x 508 mm. (26 x 20 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Dr. Peyton Eggleston, Baltimore, BMA 2011.35  Diane Victor (South African, born 1964), Smoke Screen 7 (Frailty and Failing), 2010, smoke carbon from candle over graphite, 660 x 508 mm. (26 x 20 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased in Honor of Rosalind Kronthal's Seventieth Birthday with funds contributed by her Family and Friends, BMA 2011.34  Diane Victor (South African, born 1964). Beware the Lap of Luxury, 2020. Etching (hardground and softground), drypoint, and aquatint from steel plate on Hannemuhle Copperplate paper. More specifically, line etch with three stopouts, softground with lift transfers, and softground with drawing transfer, drypoint, and three aquatint bites. Sheet: 1016 x 1168 mm. (40 x 46 in.); plate: 914 x 1067 mm. (36 x 42 in.) Edition of 18. Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press.  Diane Victor working on Beware the Lap of Luxury, 2020 at Island Press. Etching (hardground and softground), drypoint, and aquatint from steel plate on Hannemuhle Copperplate paper. More specifically, line etch with three stopouts, softground with lift transfers, and softground with drawing transfer, drypoint, and three aquatint bites. Sheet: 1016 x 1168 mm. (40 x 46 in.); plate: 914 x 1067 mm. (36 x 42 in.). Edition of 18. Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press.  Diane Victor working on Beware the Lap of Luxury, 2020 at Island Press. Etching (hardground and softground), drypoint, and aquatint from steel plate on Hannemuhle Copperplate paper. More specifically, line etch with three stopouts, softground with lift transfers, and softground with drawing transfer, drypoint, and three aquatint bites. Sheet: 1016 x 1168 mm. (40 x 46 in.); plate: 914 x 1067 mm. (36 x 42 in.). Edition of 18. Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press.  Diane Victor and Master Printer Tom Reed working on Beware the Lap of Luxury, 2020 at Island Press. Etching (hardground and softground), drypoint, and aquatint from steel plate on Hannemuhle Copperplate paper. More specifically, line etch with three stopouts, softground with lift transfers, and softground with drawing transfer, drypoint, and three aquatint bites. Sheet: 1016 x 1168 mm. (40 x 46 in.); plate: 914 x 1067 mm. (36 x 42 in.). Edition of 18. Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. Photo courtesy of Island Press. Ann ShaferWhen I’m hunting for new acquisitions, on the macro level I ask myself several questions. How does it fit into the larger collection? Is it continuing an established collecting area, or is it a wholly new avenue? Does it have friends already in the collection, and will they play well together in an interesting exhibition? And, will it be useful with students in the print room? On the micro level, other questions arise. When you find a work that is political in tone, for instance, I always ask myself, is it too specific to a certain moment that will be lost on future viewers, or is the message universal enough to be both specific and universal? Ben Levy and I invited Joseph Carroll to be a vendor at the 2012 Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair, and he brought with him Ambreen Butt's set of five prints, Daughter of the East, 2008. I loved them then and pitched them, but the proceeds from the fair went to other acquisitions. I always regretted it, so when the same set of prints showed up at the 2017 print fair with Wingate Studio, I gave a little jump for joy. (Butt’s prints were printed and published by Wingate’s Peter Pettengill, a lovely person and a great printer, and are among the last things I acquired for the BMA.) The set of five prints are delicate and strong at the same time and reflect Butt’s early training as a miniature painter (she grew up in Pakistan and studied traditional Indian and Persian miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore). In 1993, Butt moved to Boston to get an MFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She now lives in Dallas. Daughter of the East, 2008, consists of five multi-plate etchings, some with chine collé, that are a reaction to the Siege of Lal Masjid, or Red Mosque, in Islamabad, which occurred July 3–11, 2007. During the siege, the Pakistani government raided the Red Mosque complex, whose students (men and women) and mosque leaders challenged the Pakistani government. They practiced radical, conservative religious teachings, and have since been linked to Al Qaeda. When negotiations with the mosque leaders failed, the complex was stormed by the Pakistani Army’s Special Services Group, resulting in 248 people injured, over one hundred dead, and fifty captured. While at least thirty women and children were able to escape unharmed, many were reported to have been used as shields by their male allies. Subsequent reporting indicates that no women were killed, although that has long been part of the narrative. In the end, it doesn’t matter. Butt’s prints put forth the idea of women as fierce and vulnerable at the same time, of strength in numbers, and the power of the individual. In them there is both sorrow and pride, fear and purpose, belief and faith. Behind the figures, Butt takes stylistic elements of traditional Persian miniatures but creates them as aggregations of surprising objects: pistols, headwraps, helmets, ladybugs. In the first print, women, like ladybugs, gain power in numbers, even if only armed with bamboo sticks. In the second print, the figure’s burqa morphs into a dragon, which I choose to read as her power realized. In the third print, the female figure, who is specific and universal at the same time, dissolves into a splattering of ladybugs and flowers. In her ability to be one woman and all women, Butt may be referring to Indic and Buddhist philosophies in which the one and the infinite exist simultaneously. In the fourth print, the figure has dissolved into a thousand ladybugs and has assembled her power in the figure holding the rifle, ready to defend her beliefs. The final print depicts a woman with her face revealed (the artist herself), a solitary figure whose weapon is being destroyed by a woodpecker. In terms of asking those questions about political prints—does it hold up even if you don’t know to which events the prints are referring—I believe these fit the bill. For me, they portray a full range of emotions on what it is to be a woman. Although we each bring our own gifts and individuality, we need each other and are stronger together. That seems like a solid message to send out into the world as this week of protest marches and public fury at the authoritarian steps being taken by those in power comes to an end. May Butt’s images and ideas help sustain us as we stand together for what is right. And may we come out the other end with systemic change at all levels of society. Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969) Printed and published by Wingate Studio Daughter of the East, 2008 Portfolio of five color etchings with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé Sheet (each): 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate (each): 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.1–5  Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969), Plate 1 from Daughter of the East, 2008, color etching with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé, sheet: 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate: 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.1  Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969), Plate 2 from Daughter of the East, 2008, color etching with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé, sheet: 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate: 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.2  Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969), Plate 3 from Daughter of the East, 2008, color etching with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé, sheet: 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate: 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.3  Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969), Plate 4 from Daughter of the East, 2008, color etching with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé, sheet: 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate: 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.4  Ambreen Butt (American, born Pakistan, 1969), Plate 5 from Daughter of the East, 2008, color etching with aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and drypoint on chine collé, sheet: 634 × 481 mm. (24 15/16 × 18 15/16 in.); plate: 455 × 327 mm. (17 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2017 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2017.68.5 Ann ShaferOne of the best things about teaching art students is that they move on and you get to watch as they continue to blossom. I’m not in touch with all of the students who wandered through my print room, but there are a special few with whom I keep in touch and follow on the interwebs. Once such artist is Terron Sorrells, who was in Tru Ludwig’s History of Prints class in 2014, during his junior year at MICA. Tru brought classes to the BMA six times over the semester and we looked at eighty to one hundred prints per visit from Master E.S. to yesterday. (There’s just no substitute for seeing prints in person.) Tru and I taught those classes thirteen times from fall 2005 to spring 2017. During the fall 2014 class, Terron was always as close to the prints as possible with a magnifying glass in hand, clearly soaking in their history, intricacies, and beauty. The final project in History of Prints was the creation of a work using two or three prints the students had seen during the semester as jumping-off points. Sometimes non-printmaking students would produce a project in a different medium but mostly they produced prints. We saw a tapestry, a handful of drawings, a video work using Kathe Kollwitz’s Raped as its influence, and a website playing with the notion of the limited edition (when you set the number in the edition, after viewing the webpage that number of times, it would no longer load). We saw some really great prints and a whole lot of meh prints. I always noted to myself which work was that class’s winner. Terron’s print, Handouts, was the winner in the fall 2014 class. Terron’s prints from his years at MICA seem particularly relevant today as we’ve just come off a weekend full of demonstrations, some peaceful and some violent, protesting the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police. There is a through-line that winds its way from slavery through Reconstruction-era inmate leasing, Jim Crow laws of segregation, racial terror lynchings, mass incarceration, and today’s police killings. The terms may have changed, but the effect remains. Visual acts of protest in prints can be indelible markers of those moments in history, and some can remain eerily relevant even years later. Terron had his first one-person exhibition in 2019 at Strathmore Hall in Bethesda, Maryland, and it was beautiful. It was great to see Terron’s more recent paintings hanging alongside the prints from his school years. Many of the works on view had red dots marking them as sold, and additional impressions of some of the prints were available in Strathmore’s shop, because, ya know, prints are multiples. While many people take issue with that multiplicity, printmakers have long been drawn to making images in numbers that enable images to be spread far and wide. Sometimes prints are made to extend an artist’s fame or a particular composition; sometimes prints are made to make a very pointed statement about society. Prescient political prints have been produced by the likes of Jacques Callot, Francisco de Goya, Edouard Manet, Honoré Daumier, Otto Dix, Pablo Picasso, Leonard Baskin, Sue Coe, Sandow Birk, and countless others. To this list we can add Terron Sorrells. Terron’s prints often turn history on its ear. In Triumph over Kasualties, African Americans wearing whiteface swoop into a Klan rally on horseback upending the narrative. This is the most active act of resistance in this group of prints. The rest highlight somewhat quieter but no less impactful moments. In Colored Only the split frame reveals that life only exists in color on the colored side. In After That, Do This, Then This, Then That, a multi-appendaged domestic worker is keeping the household running as the white woman boops her on the nose. The shadow of her head is reminiscent of a figure in Pablo Picasso's monumental and monumentally important painting, Guernica. In Handouts, Cooper has crossed out the identifying label “negro” to remind viewers that there are individuals behind labels. These prints are pointed, beautifully executed, and quiet, but they pack a wallop. While I really like Terron’s new paintings, I hope that someday he will return to printmaking, for his is a strong voice that is needed now more than ever. Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Handouts, 2014 Etching 279 x 356 mm. (11 x 14 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Gumptious Stroll Through Stagville Estate, 2014 Etching 279 x 330 mm. (11 x 13 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Triumph over Kasualties, 2015 Etching 356 x 508 mm. (14 x 20 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Press Forward, 2015 Etching with chine collé 127 x 178 mm. (5 x 7 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Picket, 2015 Etching with chine collé 279 x 381 mm. (11 X 15 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Colored Only, 2016 Lithograph with chine collé 381 x 533 mm. (15 x 21 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) After That, Do This, Then This, Then That, 2016 Lithograph 381 x 533 mm. (15 x 21 in.) Terron Sorrells (American, born 1994) Black Lives Matter, 2016 Monotype 444 x 508 mm. (17 ½ x 20 in.) |

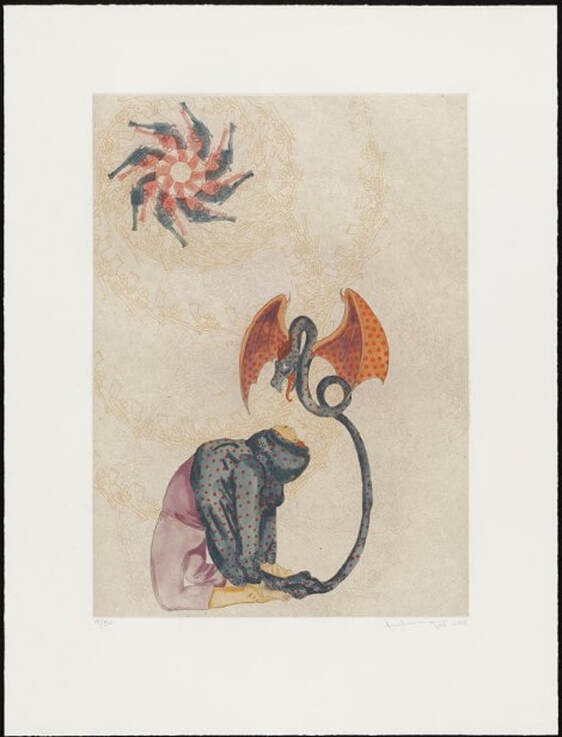

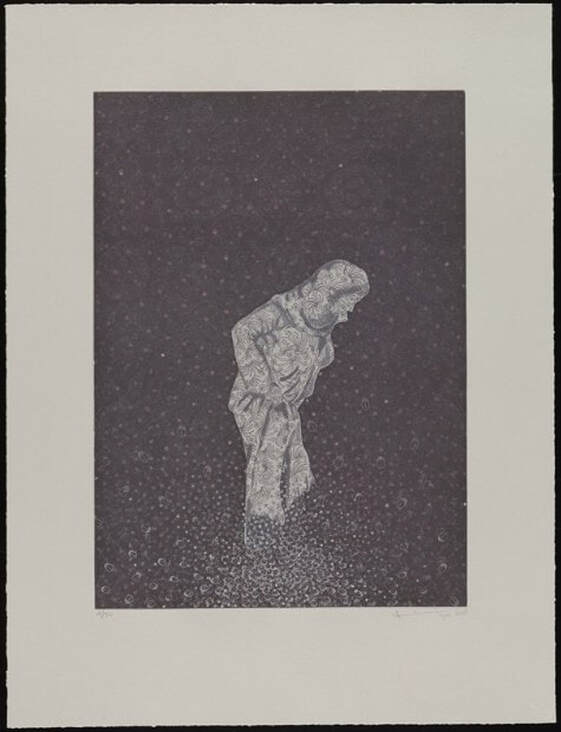

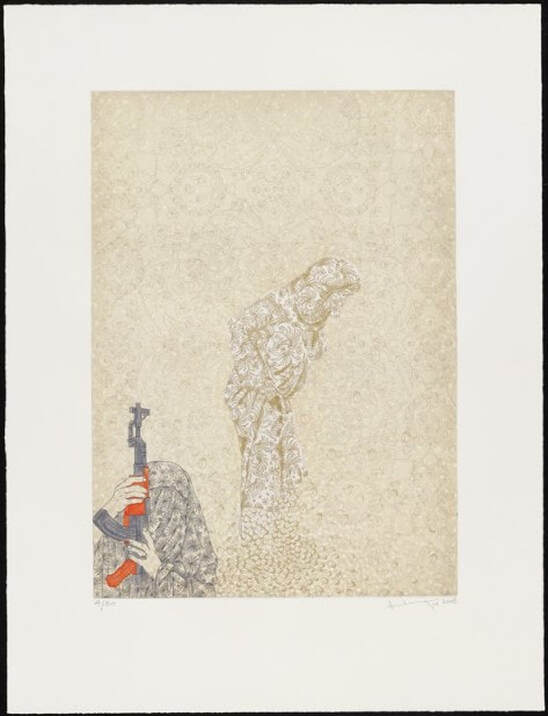

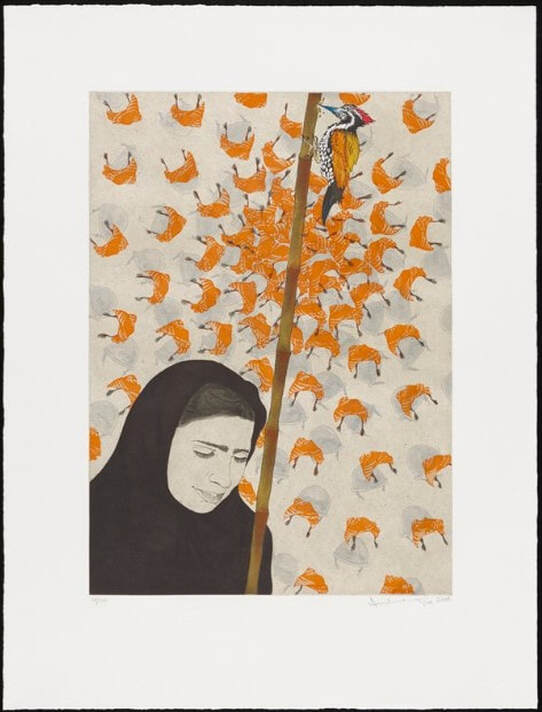

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed