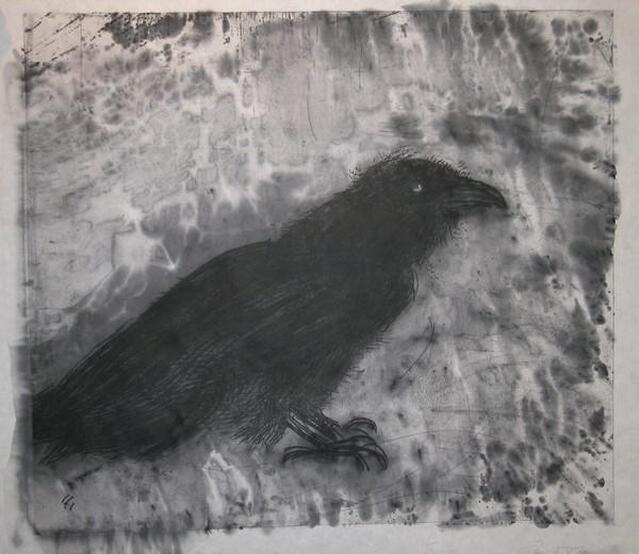

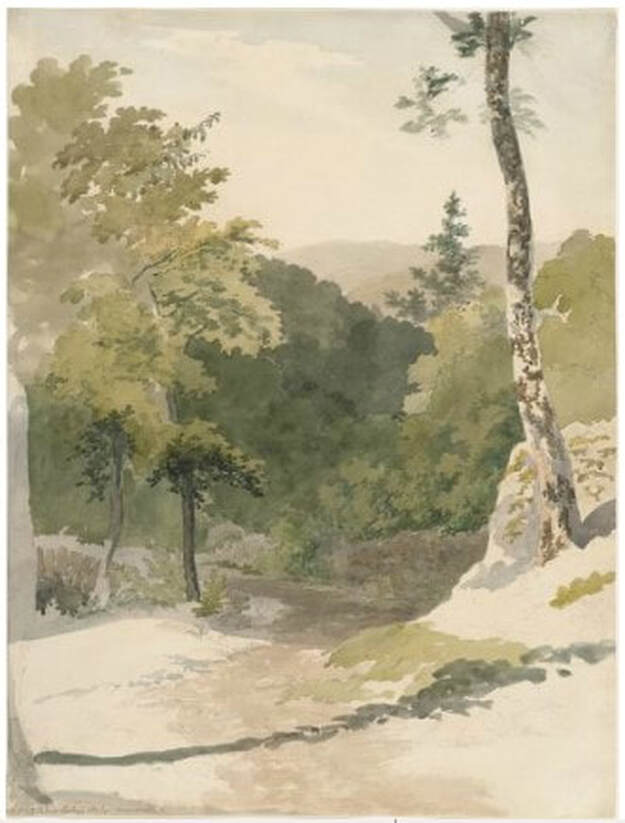

Ann Shafer A year ago, today, a few weeks into the first lock down in March 2020, I found my voice. It had been 2.5 years since I left my position as a museum curator and 2.5 years of mourning said career. I’ve said it before: I never wanted anything else but to be a curator. Certainly it is a career choice that has its flaws, not the least of which is the dismal remuneration. I can’t think of a more highly educated and underpaid group of people than those working in the museum sector. It’s appalling, really. So, after 2.5 years of depression, it took a world-wide pandemic to get me off my ass. The truth is, I was terrified that if I were taken out by Covid-19, which in those early days seemed entirely possible (recognizing my privilege here in my ability to work from home), there were a few things I wanted to have said out loud. I wanted to leave some trace of my legacy in the field, some record that my kids could refer to later and say, hey, my mom did a thing. The plan was to share stories about the many objects I acquired for the museum’s collection, which, by the way, are the things I miss the most. They all feel personal to me: I found them, researched them, prepared a convincing pitch, and got them through the system. I even got some of them hung on the museum’s walls—no easy feat. I miss being able to look at them at will and I miss sharing them with visitors. But, in truth, these posts are sort of equivalent to sharing objects in the studyroom. Nothing will ever replace seeing a work in person, of course, but this is something I can do to share my passions with you. Back in March 2020, I started with a short entry on Jim Dine’s Raven on Lebanese Border, 2000. Second, I dropped way back to 1807 to talk about a British watercolor by Robert Hills. In these first two selections you can sense how all over the place I am. And that is what I love about working with prints, drawings, and photographs. You can be deep in Rembrandt one day, pop up to Elizabeth Catlett the next day, divert to Edouard Manet for a bit, skate by Robert Blackburn, and end up at Ann Hamilton. Perfect for a curious person with a mild case of ADD. I intended to write about every acquisition I made for the museum, one per day, and keep them short and pithy, but I couldn’t keep up that pace. Besides, there are many other objects and topics about which I want to write. Since I started a year ago, I’ve written eighty-plus entries. To tell you the truth, the writing is the easy part. Gathering the images and all the tombstone information takes the most time. But the enterprise gives me great satisfaction. I am always excited to share a cool print or beautiful drawing with people I know will appreciate it. I hope you keep reading, learning, and enjoying these posts.  Jim Dine (American, born 1935). Published by Pace Editions, Inc., New York; printed by Julia D'Amario. Raven on Lebanese Border, 2000. Sheet: 781 × 864 mm. (30 3/4 × 34 in.); plate: 676 × 768 mm. (26 5/8 × 30 1/4 in.). Soft ground etching and woodcut with white paint (hand coloring). Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, BMA 2007.224.

1 Comment

Ann Shafer Let’s talk about monoprints, selective wiping, and variable etching. With printing intaglio plates (intaglio is Italian for incising a design into a plate, usually copper or zinc, and is the umbrella term under which we find engraving, etching, drypoint, etc.), the default is to ink the plate so that the incised lines carry ink that will transfer to damp paper as it is put through a press under immense pressure. If that basic image is wiped tight (meaning virtually no ink left on the surface), you’ll get the image and nothing extra. Not a bad proposition, necessarily. But, over the centuries, artists have experimented with leaving some ink on the surface of the plate to add some tonality and atmosphere. Add even more ink to the surface and something entirely new is created. Read on about a great example of this kind of additive inking.

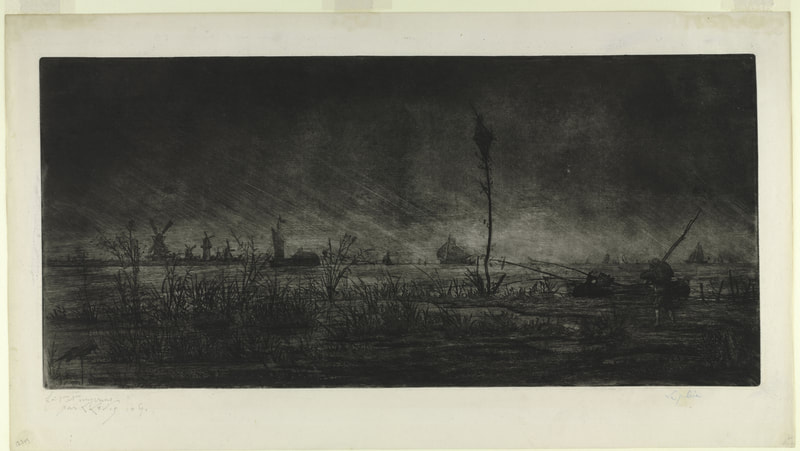

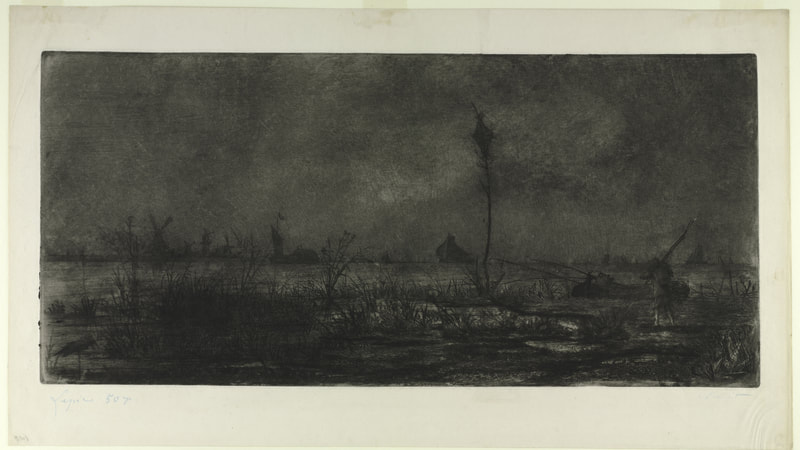

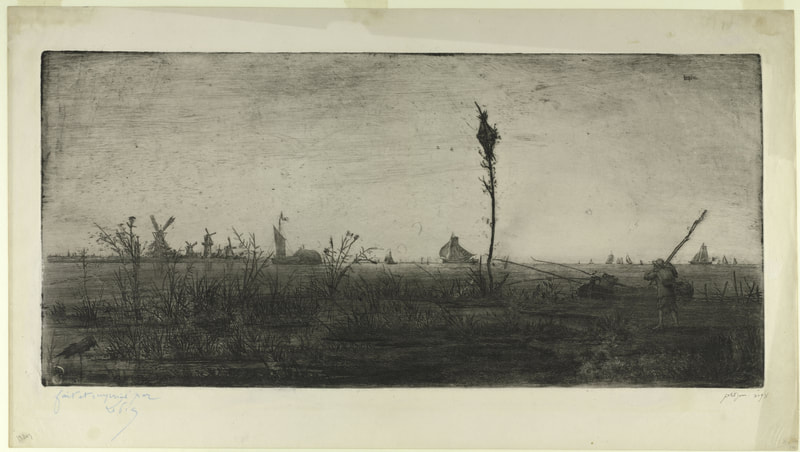

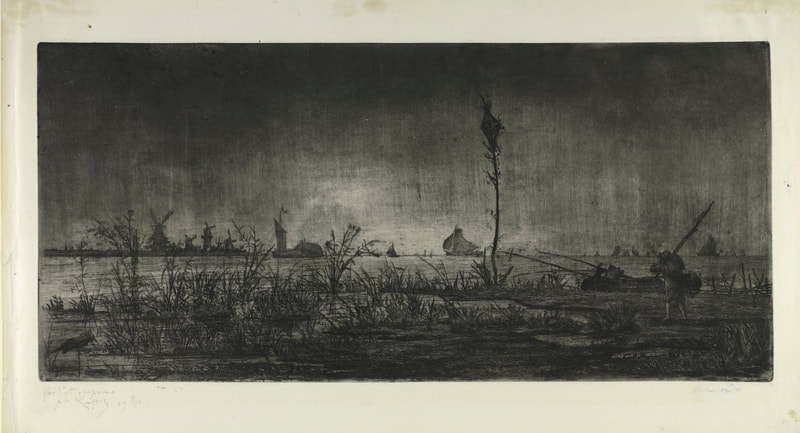

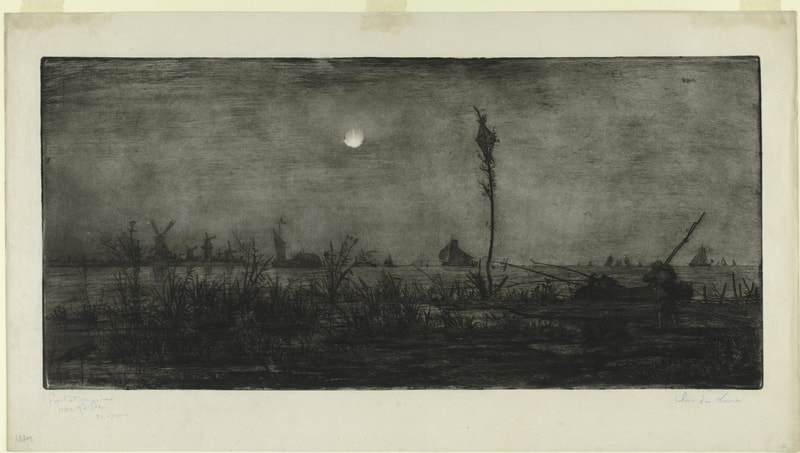

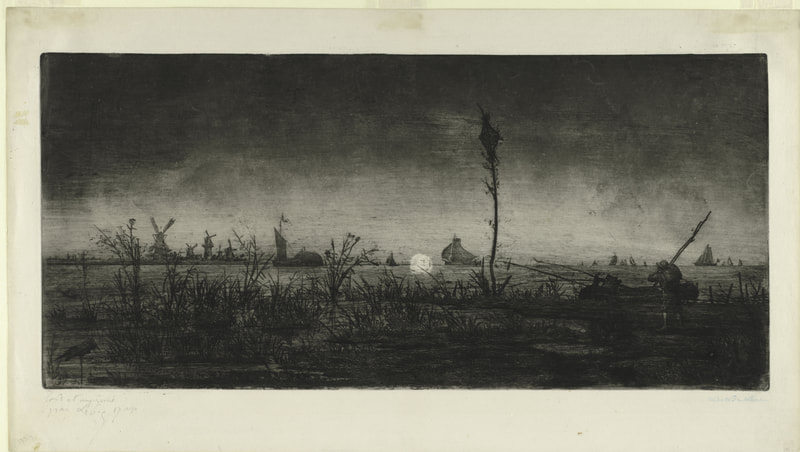

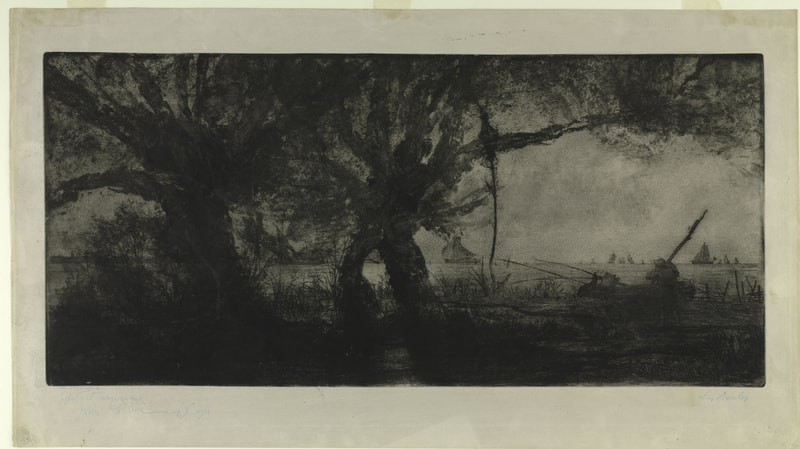

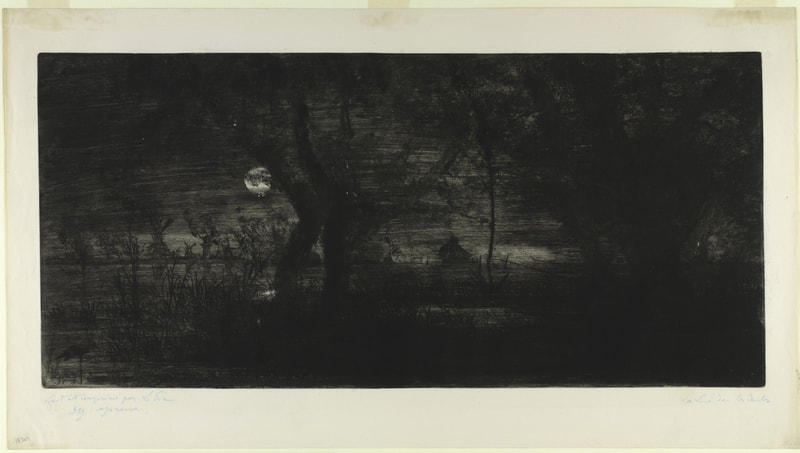

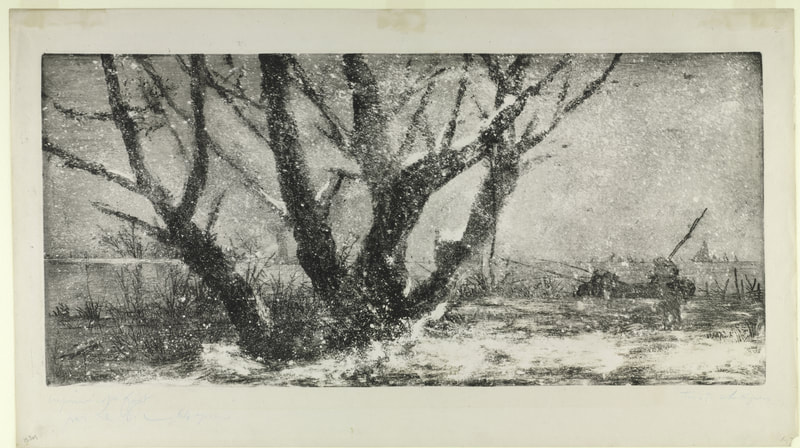

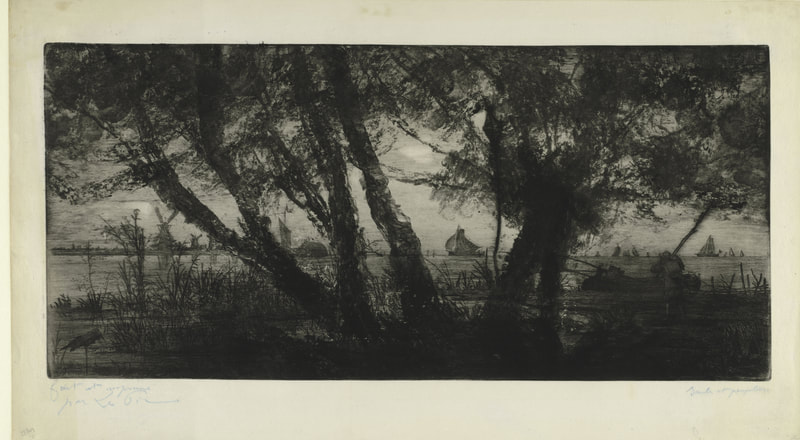

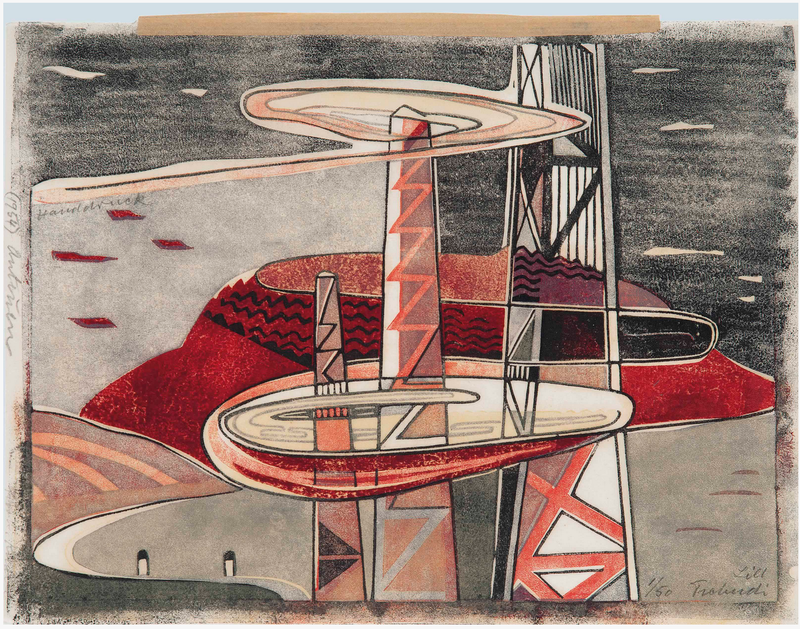

Back in 2011, the museum mounted an exhibition called Print by Print: Series from Dürer to Lichtenstein. It included twenty-nine series of prints—each in its entirety—and looked at seriality and the many reasons artists work this way. You hardly ever get the chance to see complete series of prints framed and on the wall, and the show included series that are heavy hitters in the history of prints. Some of the highlights included Durer’s Apocalypse and Piranesi’s Carceri, Jacques Callot’s Miseries of War, Ed Ruscha’s News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews, and Dues, Sherrie Levine’s Meltdown, and Andrew Raftery’s Real Estate Open House. The exhibition really was a feast for the eyes. But the most remarkable was a group of etchings by Vicomte Ludovic Lepic (French, 1839–1889). I’m gonna guess you’re thinking, who? Lepic was one of the artists who pushed variable wiping to its fullest. These are what we now call monoprints (it’s easy to get confused by the difference between monoprints and monotypes—monoprints start with some image already in the matrix; monotypes are created on a surface that carries no image so each is entirely unique). Twenty impressions of Lepic’s plate were grouped together on the longest wall in the show, each with a different look. They are among the gems of the BMA’s print collection. To be honest, the set of twenty variably wiped etchings doesn’t really qualify as a series. They were not intended to be published as a complete unit. Rather they are a substantial group of prints that are aligned because they use the same matrix in their creation. (Notice my use of the word set to describe them, rather than series. This is bringing out the cataloguer in me.) In fact, I believe Lepic made more versions of this etching, which the BMA does not own. That they don’t strictly fit into the defining principle of the exhibition is not a huge deal, really, especially when they are so instructive, mind-bogglingly beautiful, and can hold any wall anytime anywhere. The etching is a scene on the Scheldt river, which flows northward from France through Belgium and into Holland. First up is an impression wiped tight, meaning no extra ink was left on the surface of the plate. After that follow plates in which ink has been added to the surface to create wholly other compositions: weather effects, different times of day, and the addition of entire trees. They are wonderful examples of how variable wiping can completely alter an image in the best ways. Ludovic Lepic was a French aristocrat who is best known as an etcher and as the subject of several paintings by his good friend, Edgar Degas. Lepic was a painter and sculptor, a costume designer, an amateur archeologist (he founded an archeological museum), a breeder of dogs, an avid sailor, and an equestrian. But for us, his variable etching technique (he called it eau-forte mobile) had a huge impact on modern printmaking. Lepic learned etching from Charles Verlat (1824–1890) and created his first significant etching in 1860. He rapidly became a skilled etcher and in 1862 was invited to join the Société des Aqua-fortistes (The Society of Etchers), formed by art dealer Alfred Cadart (1828-1875) and others to publish original etchings. His etchings were exhibited in annual Salons from 1863 until 1886. Lepic was also involved with the Impressionists. Degas invited him to join with fifteen other artists to form an association to sponsor independent exhibitions, which lead to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. Lepic helped plan this seminal exhibition and showed seven works, watercolors, and etchings. He also showed forty-two works at the 1876 Impressionist exhibition. In the ensuing years he continued to paint, make etchings, create costumes for the Paris opera, and work on his sailboat. He died in 1889. Please meet Ludovic Lepic. Ann Shafer While I object to designating a single month to paying attention to women--why four weeks per year and why is this really necessary--here we are. I recently (not during the designated month--horrors!) wrote about some early female printmakers: Diana Scultori, Elisabetta Sirani, and Geertruydt Roghman. But, if you’ve been following along, you know my heart is in the twentieth century. So, please meet Lill Tschudi (1911–2004), a Swiss artist best known for her multi-color linoleum cuts of 1930s London.

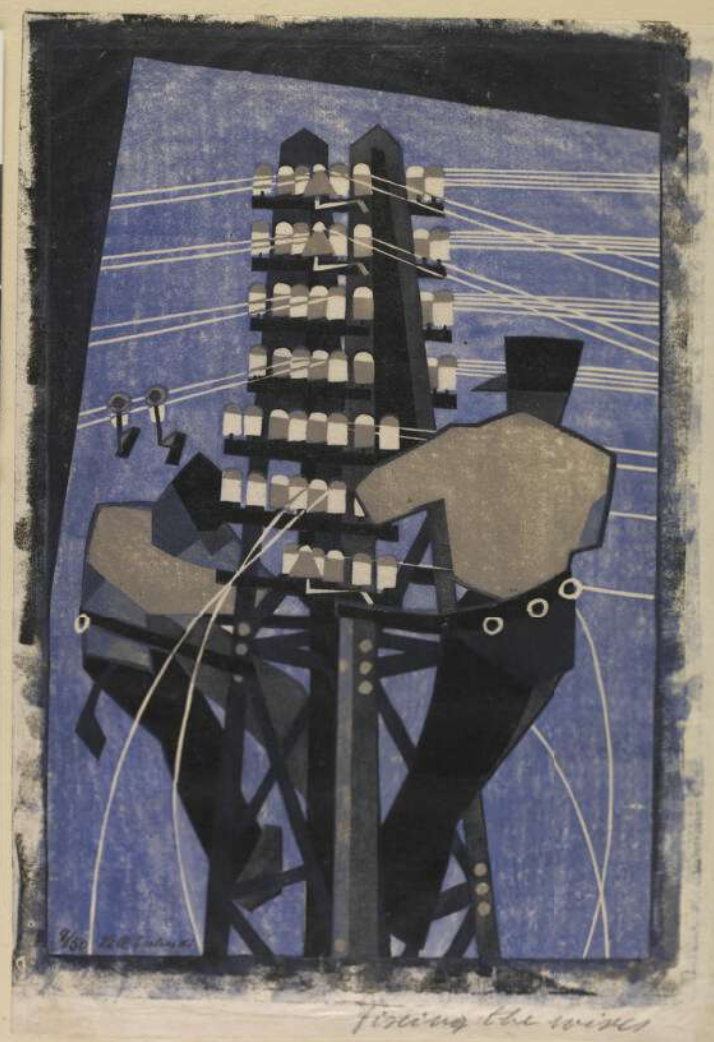

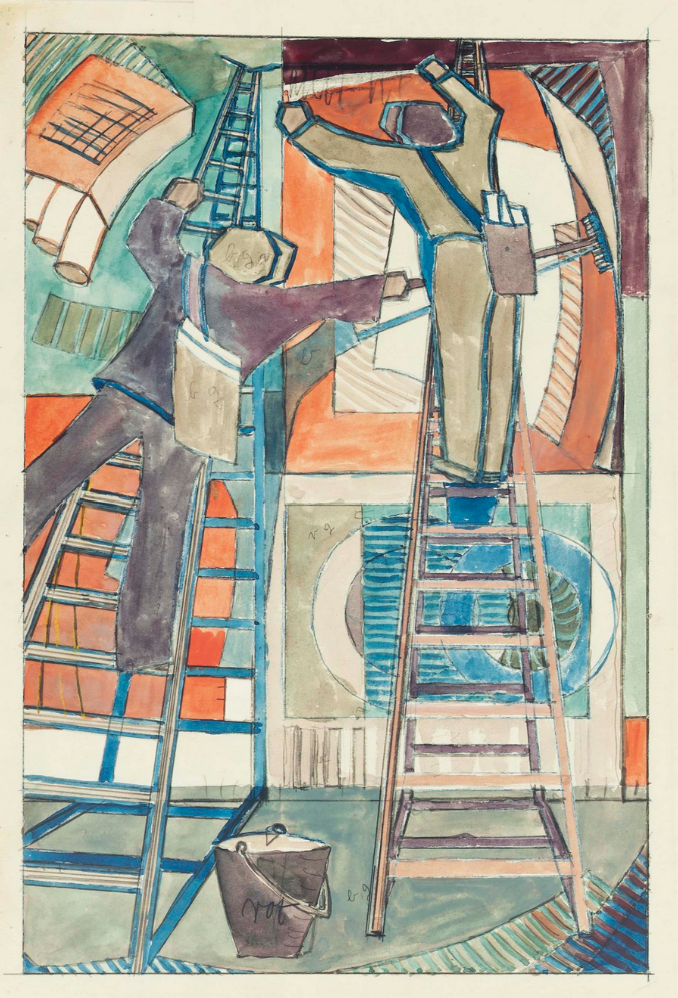

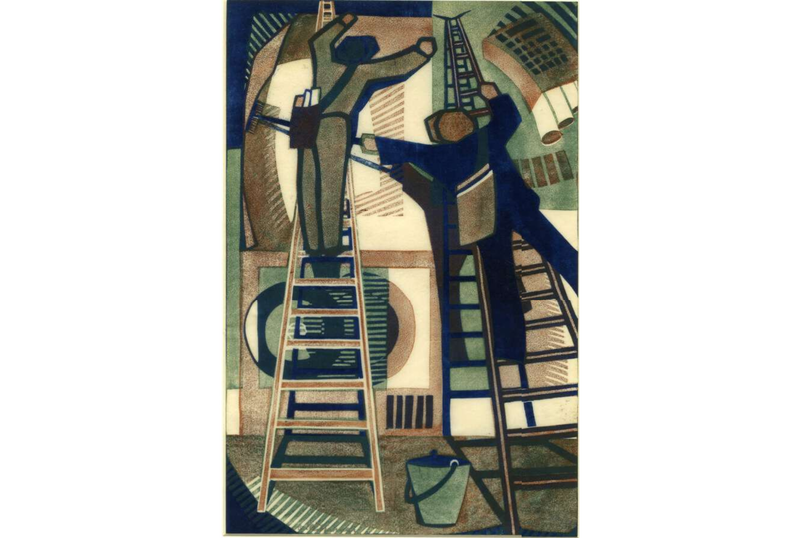

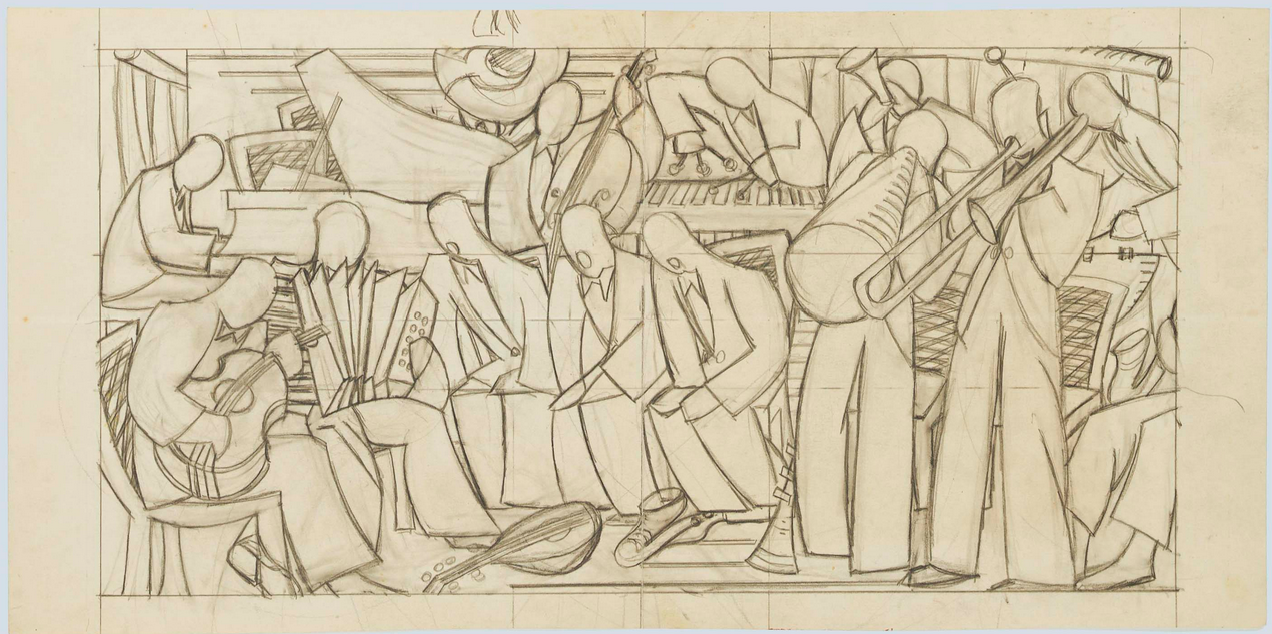

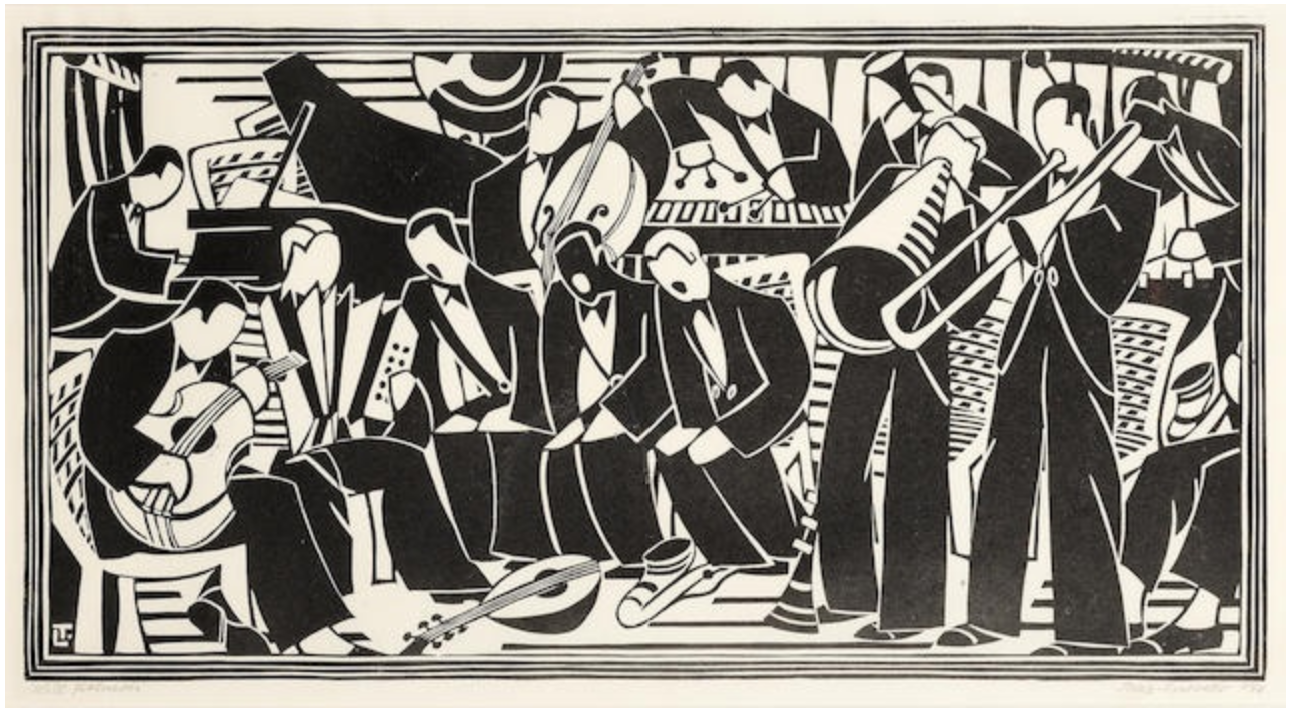

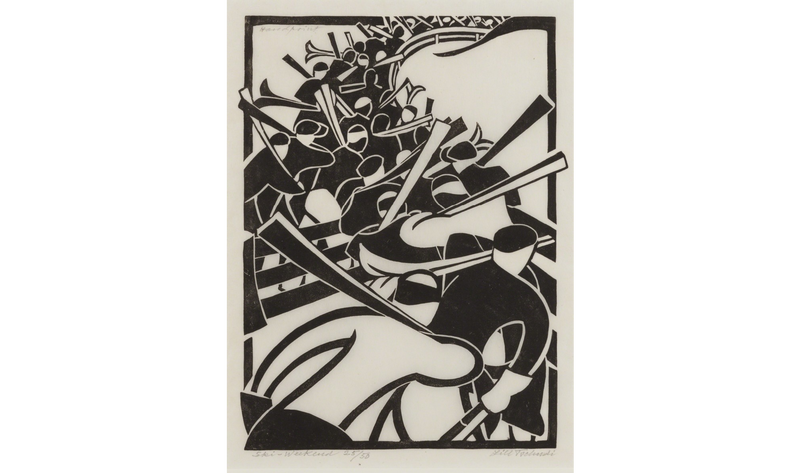

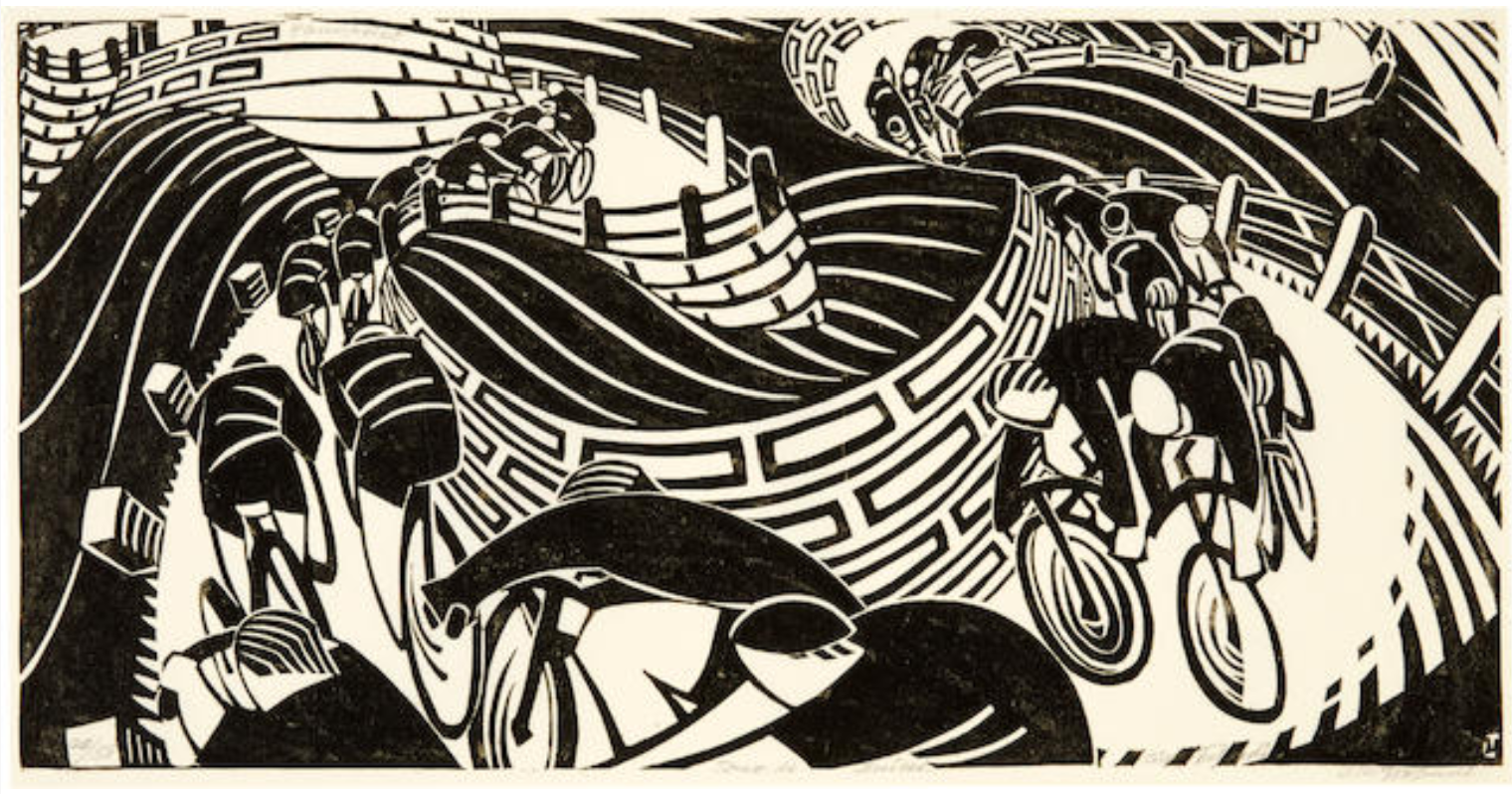

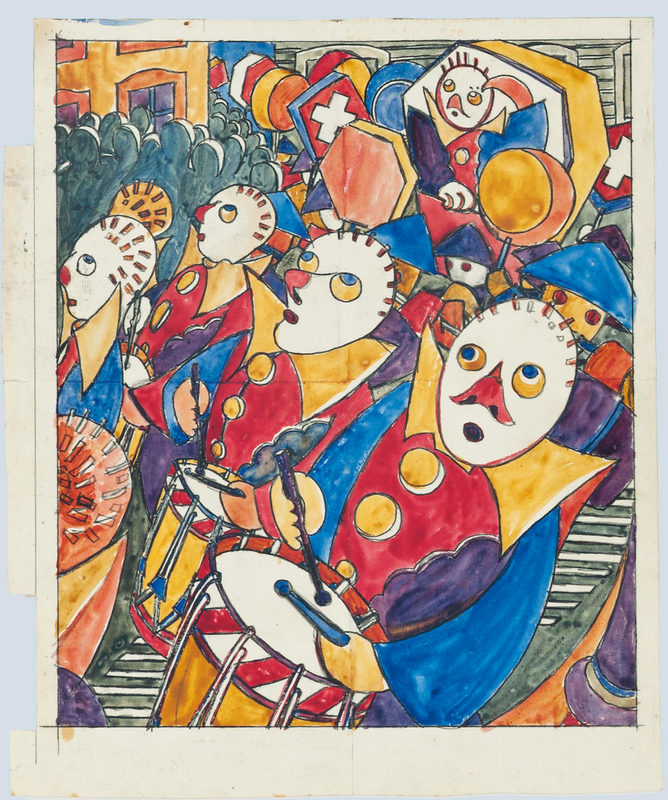

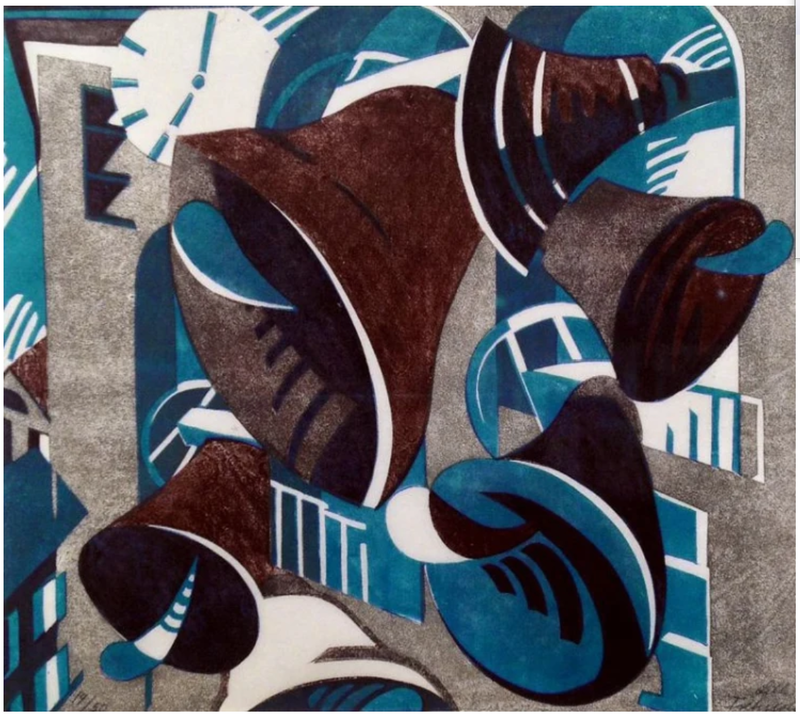

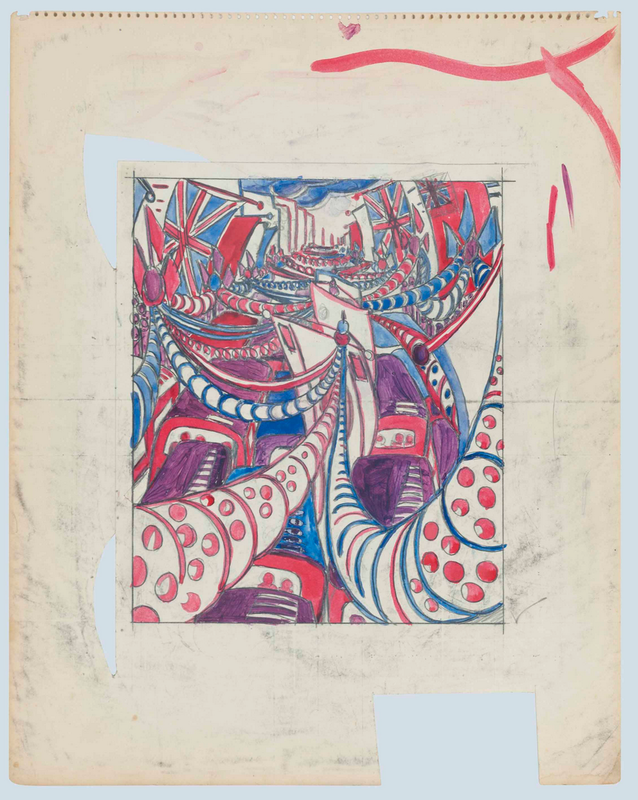

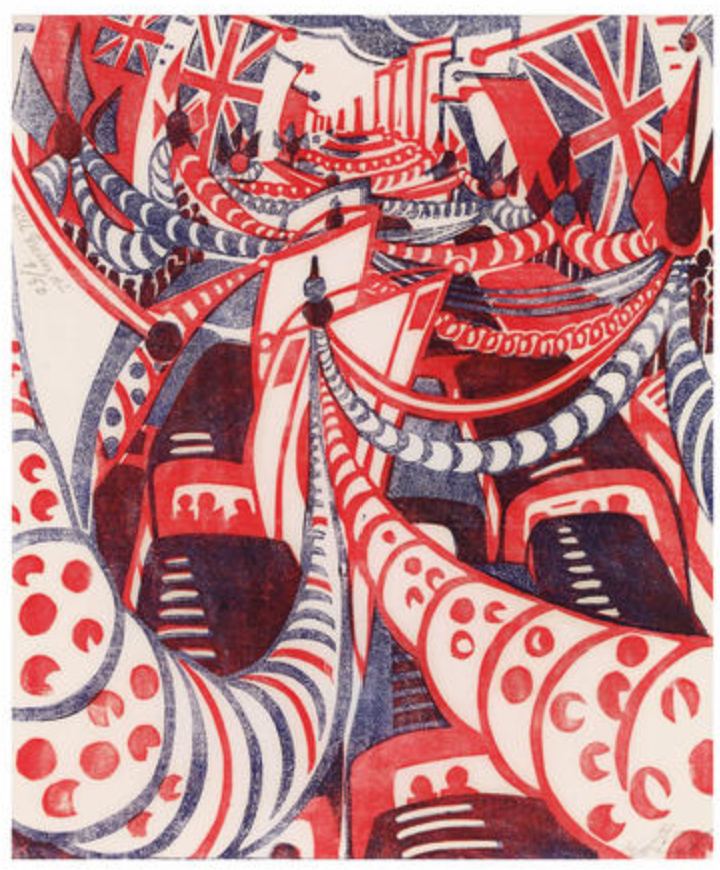

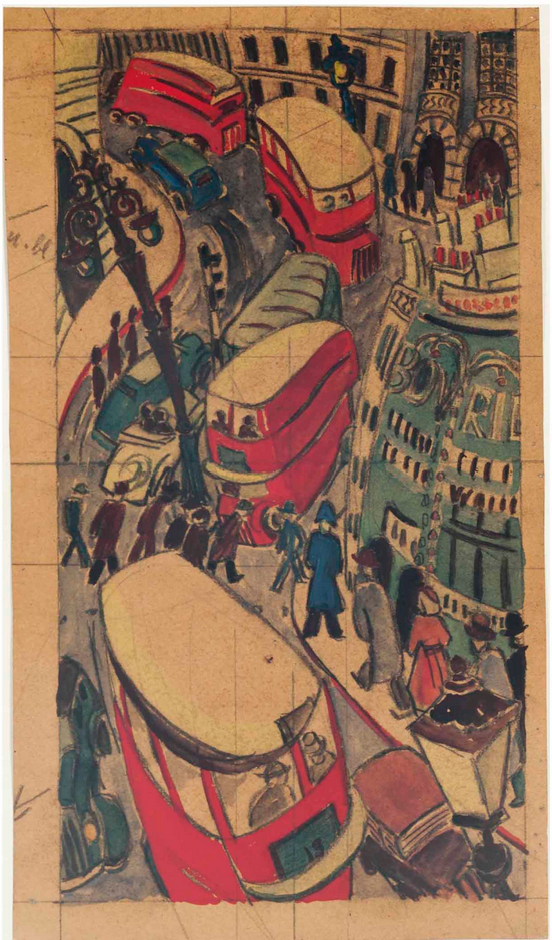

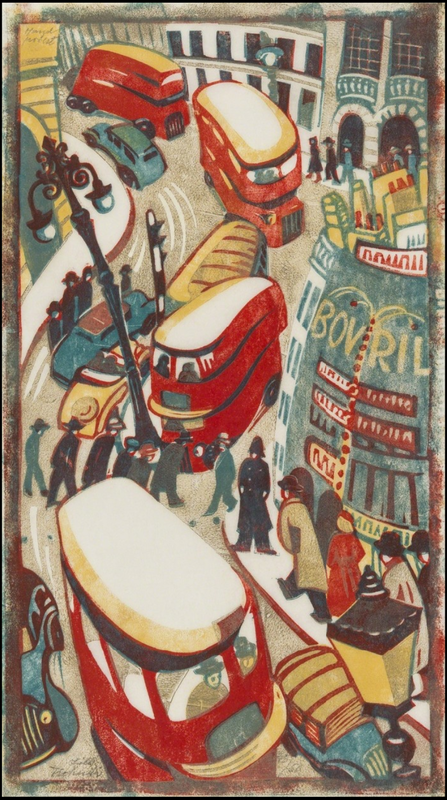

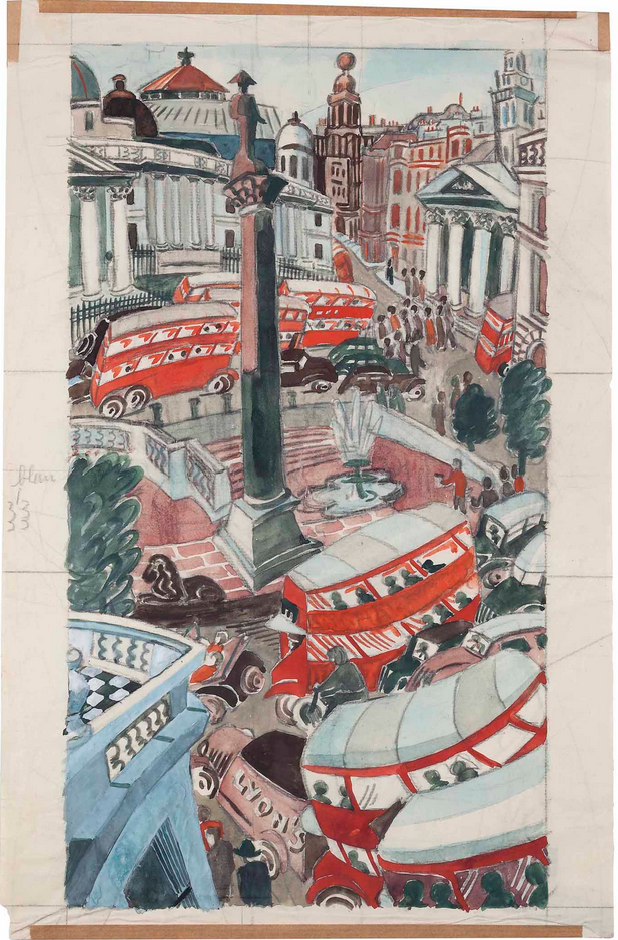

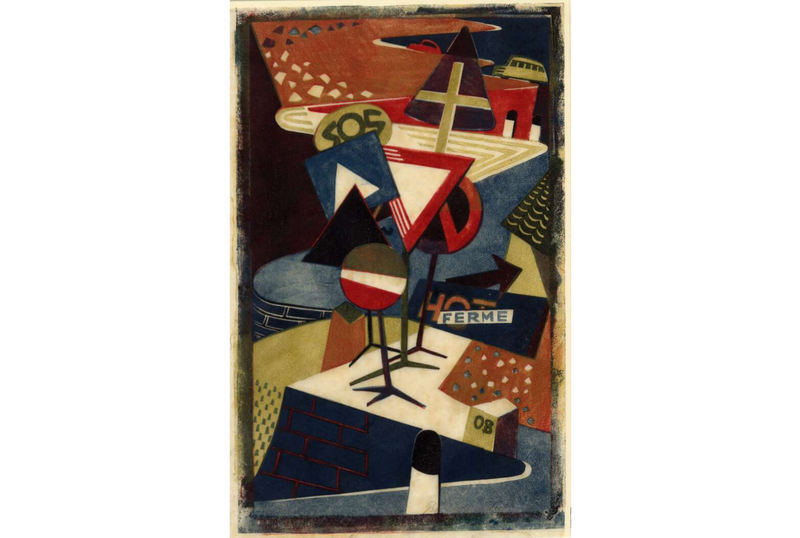

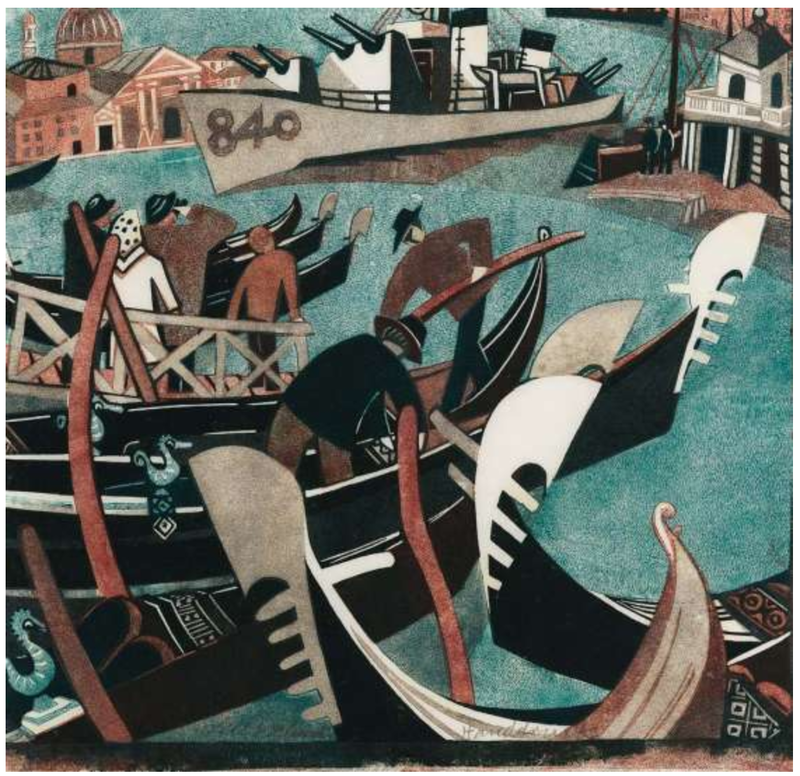

As a teenager Tschudi had already decided she wanted to be a printmaker after seeing an exhibition of prints by Austrian artist Norbertine Bresslern-Roth (she's worth a look). Determined to pursue printmaking, Tschudi spent two years (1929–30) in London beginning at age eighteen, studying with Claude Flight, a key member of the Grosvenor School, a group of printmakers making color linoleum cuts. Other members include Sybil Andrews, Cyril Power, Dorrit Black, and William Greengrass. The artists of the Grosvenor School used multiple blocks of linoleum—one for each color—to create images that celebrate modernity and the machine age in a signature style that exploits rhythmically dynamic patterns. Subjects range from the London underground’s labyrinthine stations and escalators, and horse, car, and bike races, to farmers and other manual laborers, and musicians and other performers. (Linoleum was a fairly new material used in the arts. It had been invented as floor covering in England in 1860 and later was adapted to printmaking.) After two years studying with Flight, Tschudi spent several years in Paris before returning to her native Switzerland. In Paris she studied with cubist artist André Lhote, futurist artist Gino Severini at the Academie Ronson, and Fernand Léger at the Académie Moderne. By 1935 she was back at home in Schwanden, a village in a mountainous region in eastern Switzerland known for its textile industry. In the ensuing years she made more than three hundred linoleum cuts and maintained a business relationship with Flight, who acted as her dealer in England where most of her works sold. So why am I attracted to her prints--well, all of the Grosvenor School, really? I’ve always loved bold graphic images. I love a stripe, a circle, a square, anything geometric; I am much less attracted to paisley or anything fussy. I have often wondered if it goes back to the mid-century modern décor I grew up with in the late sixties and seventies (love me some Marimekko). Cuz, you know, it’s all what you grow up with. I also love it when forms are reduced to their essential elements. And how cool is it that she got motion out of those reductive forms? I just love them. Lucky for us, a large collection of works by Tschudi sold at Christie's in 2012, including a number of preparatory drawings for prints. You'll find some here along with their prints. Ann Shafer The Big Bang. How do you express the formation of the planet and its inhabitants, and what kind of craziness had to come together to create the elements that, put together, make humans capable of thought, creativity, love? It’s really all dumb luck, isn’t it?

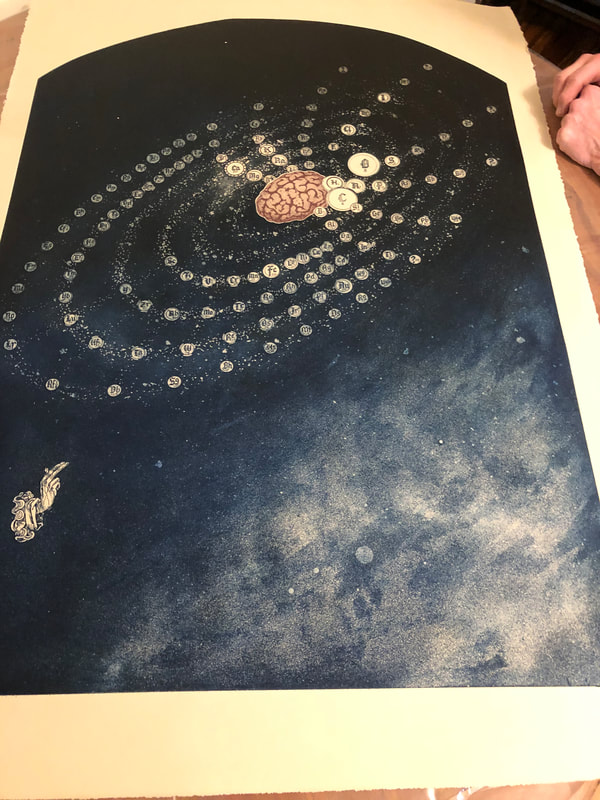

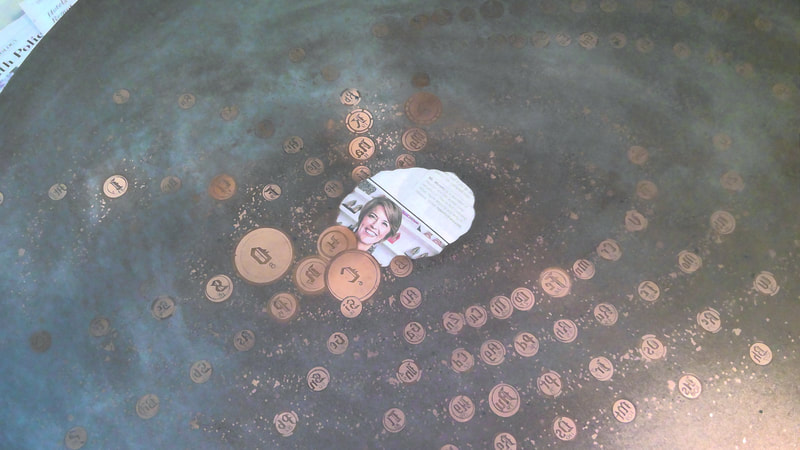

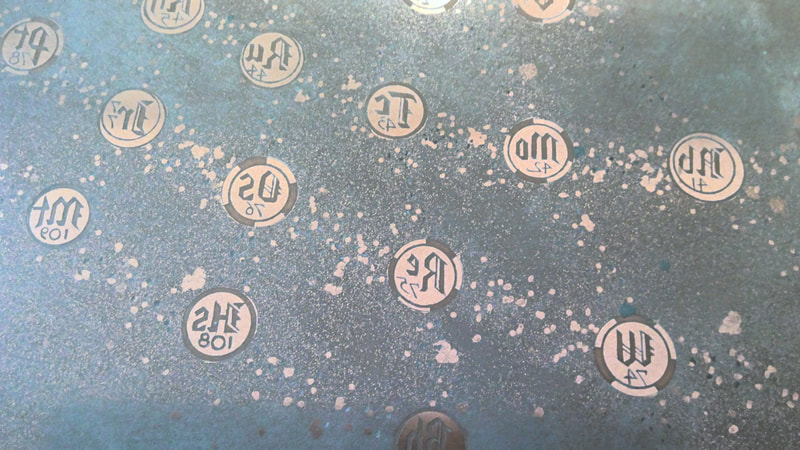

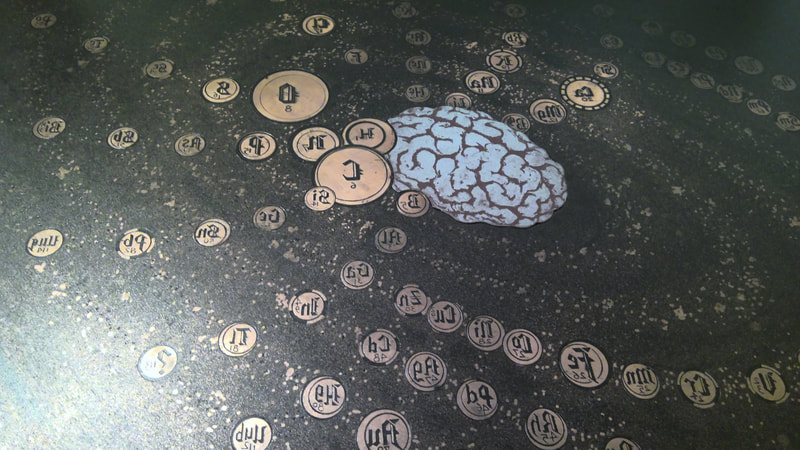

I recently helped Tru Ludwig print a rather large etching tackling this concept, Dumb Luck, 2009. The composition is a ring of periodic table elements swirling around a human brain set against a galaxy of stars. That brain is a zinc plate cut to fit into the center of the copper plate. The image is printed in blue-black (on the copper plate) and deep red (on the zinc plate). Scribing the element symbols took Tru three months to complete. I believe it. They are intricate, delicate discs floating on an aquatinted galaxy of stars and planets. Three bright white, far-off stars are drilled holes in the plate that carry no ink. They are a small yet vital part of the composition. Then there is a set of blessing hands at lower left. So, in addition to pondering the dumb luck that enables our existence, it raises questions about whether a higher power had a hand in our design. I love this print. I’ve always loved looking at pictures of the stars and galaxies and I’ve always been amazed by the Big Bang theory. How could it be that all this was created without some sort of intentionality? I’m not a particularly religious person, but it does make one wonder. That Tru figured out a way to convey this mystery astounds me. You may recall that Tru and I printed another of his prints, Ask Not…, last weekend, during which I was sort of helpful. I think I graduated to really helpful printing Dumb Luck. By the end of the session, I was wiping that little brain without supervision. I was wiping those element discs. I even came up with a method of quickly removing the first layer of ink—I’m pretty proud of that. We fell into the print-shop ballet that will be familiar to anyone who prints. I loved being in the studio and it reignited my long-held desire to open a print shop and publish prints. If only I would win the lottery in order to be able to do so. <sigh> Ann Shafer There’s one part of being a curator that may shock you. There is no requirement that a curator has ever made a work of art in the manner of those objects they study and work with on the job. I mean, they have to know the basics and be able to describe them, but they don’t have to have done it themselves. I’ve watched lots of demos, made a linoleum cut in grade school (still have the scar to prove it), and I’ve been on hand during the printing process, but have always been the extra pair of hands. I’ve never inked, daubed, wiped, and printed a plate. Until recently, that is.

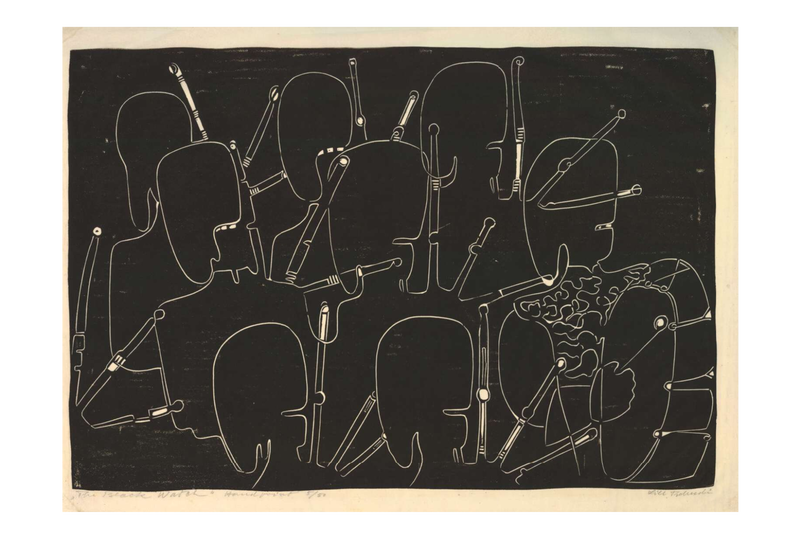

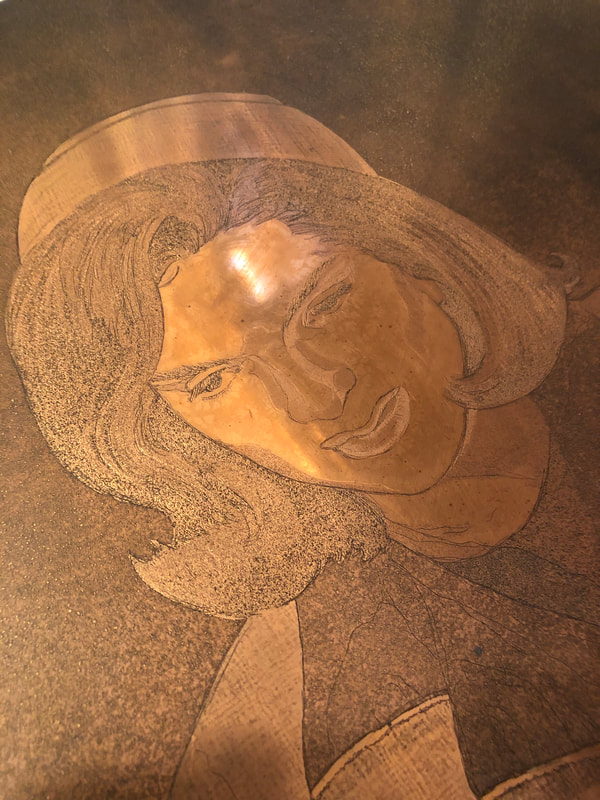

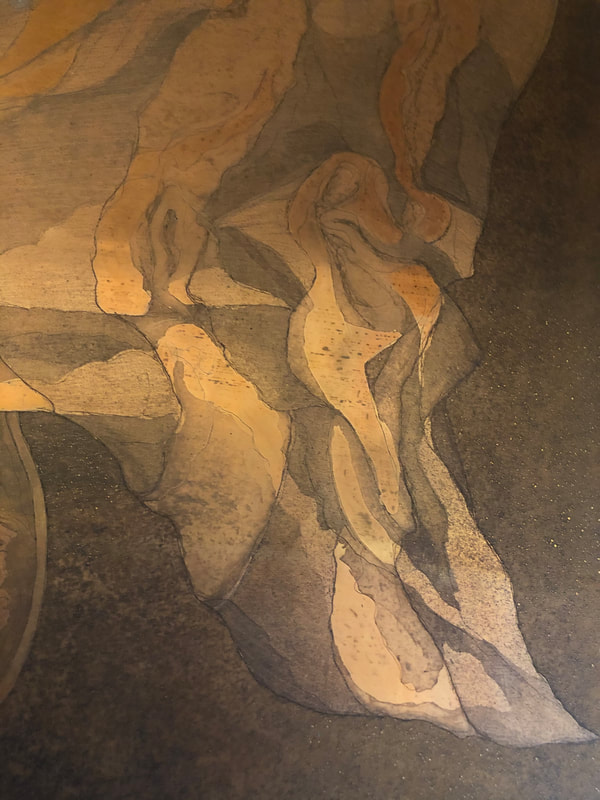

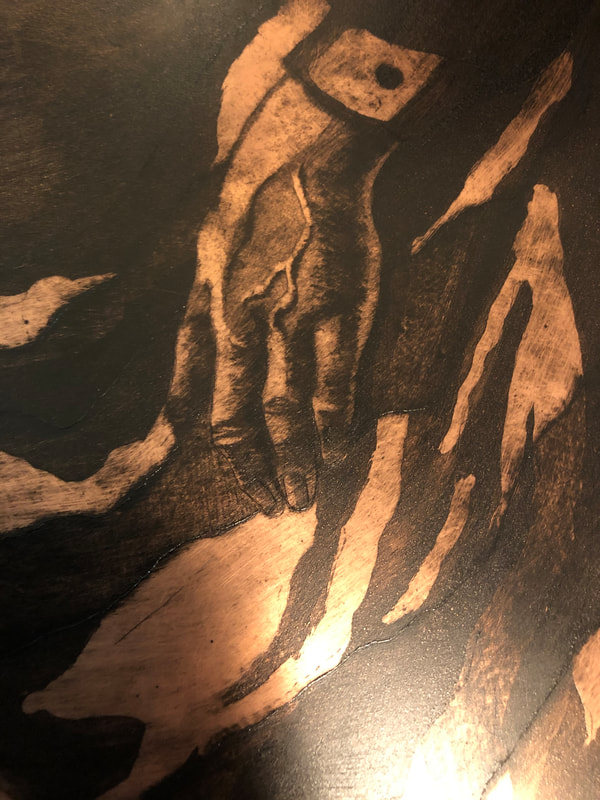

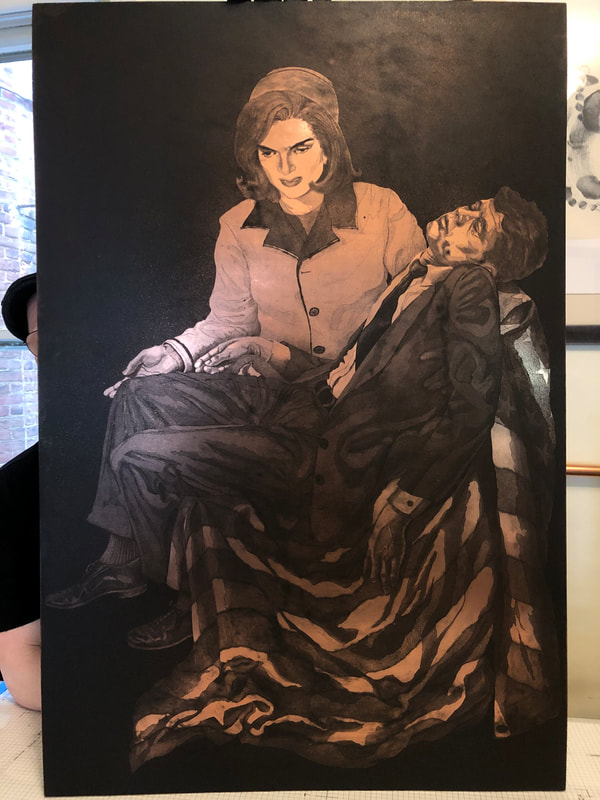

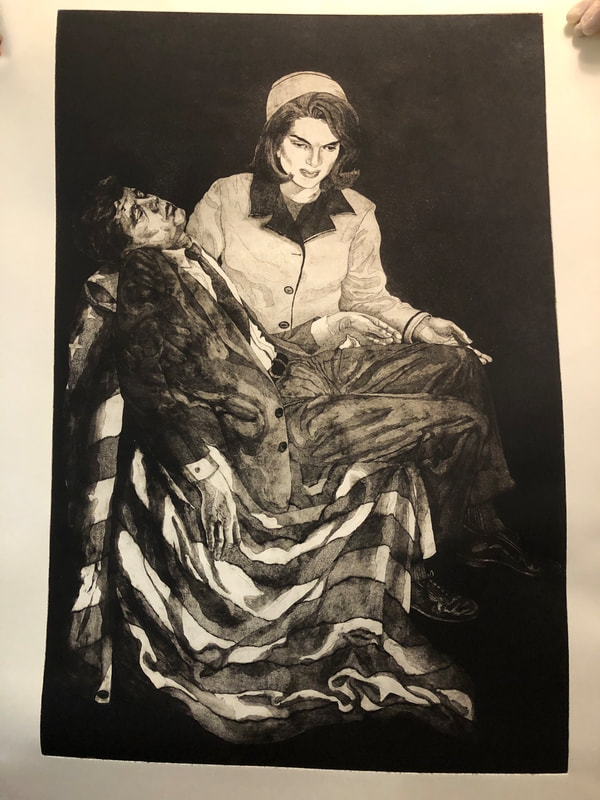

If you’ve been following along, you know that Tru Ludwig and I have been friends and colleagues for a good long time. Tru is the MICA professor with whom I taught history of prints for over a decade. I have also told you that Tru and I have traveled together to take in exhibitions and art fairs: New York, Philadelphia, Washington, London, Paris. We’ve shared a lot of hotel rooms, meals, and more than our share of vodka martinis (dirty and really dirty, respectively). But you probably don’t know that Tru is a kickass printmaker. I’ve always admired his woodcuts—there is one in the Baltimore Museum’s collection and I used it frequently for classes in the studyroom. And I’ve seen just about all of his other works. But one had always eluded me, Ask Not...—I’d only seen it in a pretty bad, discolored reproduction. But I knew it was special and that I would give a lot to have an impression. Lucky for me, the plate for Ask Not..., with Jackie and JFK as Pietà, is in fine shape, even after sitting in storage for twenty plus years. After a bit of Weenol, it was ready for its closeup. We managed to pull three impressions on Saturday. Jeepers, it’s a big plate. I was surprised by the amount of ink needed to cover the plate, both less and more than I thought. I was surprised how long it took to wipe the plate. I was surprised by how many variations of wiping went into the enterprise. And it confirmed for me that wiping and printing are just as critical as the making of the plate. It really was an education. And of course, there’s no better teacher than Tru. So, the print, Ask Not.... It’s a mash up of a critical piece of American history portrayed in the manner of an important Renaissance artwork by none other than Michelangelo (love a nod to art history), and turns the focus to not the main character (JFK), but a supporting one (the first lady). Tru’s etching gives us Jackie Kennedy holding the limp, dead body of President Kennedy on her lap in the same way the Virgin Mary holds the dead Christ in Michelangelo’s glorious marble sculpture. (If you’ve never seen the Pietà in St. Peter’s at the Vatican, don’t miss it if you get to Rome. Seriously.) It’s a simple gesture, but so full of meaning, emotion, power. (Remember, less is sometimes more.) Sometimes an image socks you in the gut. Like the Virgin in the Pietà, the image of Jackie holding JFK reminds us of her grace under extraordinary circumstances. Here she is still wearing the pink suit that had been splattered and soaked with the blood of her husband. It is well known that the first lady kept that suit on throughout the long day following the death of the president. She understood the power of images and was heard to say: “let them see what they've done." JFK is being cradled by an American flag, which seems to puddle along with our hope for the future. Tru’s draftsmanship is spot-on. And there’s something about the action of the corrosive acid used to etch the copper plate that lends itself to the subject. It feels like the copper is fighting to be turned into something, in the same way that we are fighting to be seen and heard and acknowledged. That the country’s sorrow should not be in vain. That at this point in our history, we should take a moment to remember what we have all fought for, and what so many have died for. There’s something at once delicate and harsh about the technique and about the subject. A pure confluence of content and method. It all feels more timely than ever. Ann Shafer I gave a talk to the Lewes (Delaware) Historical Society last week. With the option to talk about anything, I focused on American prints from 1900-1950. Fair warning: it runs nearly an hour. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed