Ann Shafer Let’s talk about monoprints, selective wiping, and variable etching. With printing intaglio plates (intaglio is Italian for incising a design into a plate, usually copper or zinc, and is the umbrella term under which we find engraving, etching, drypoint, etc.), the default is to ink the plate so that the incised lines carry ink that will transfer to damp paper as it is put through a press under immense pressure. If that basic image is wiped tight (meaning virtually no ink left on the surface), you’ll get the image and nothing extra. Not a bad proposition, necessarily. But, over the centuries, artists have experimented with leaving some ink on the surface of the plate to add some tonality and atmosphere. Add even more ink to the surface and something entirely new is created. Read on about a great example of this kind of additive inking.

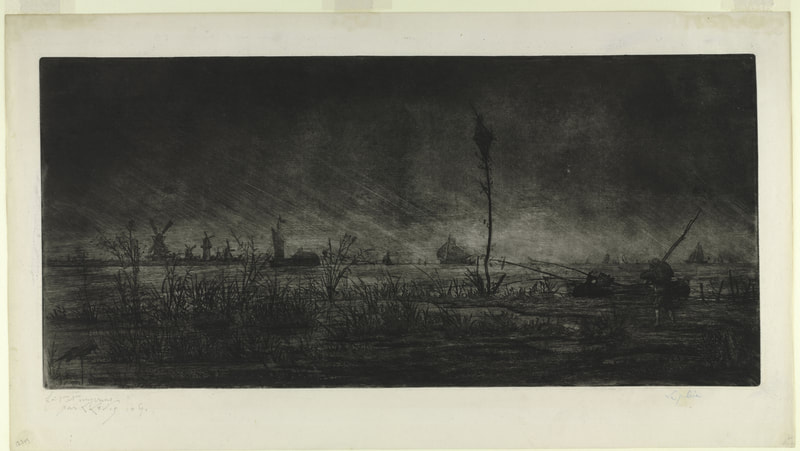

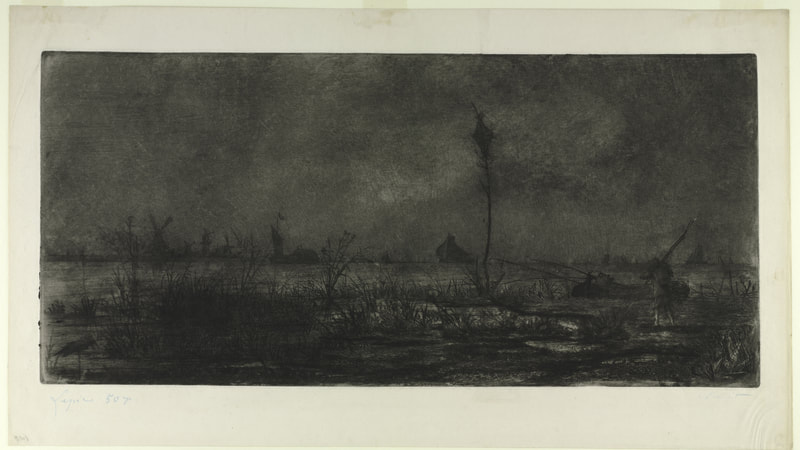

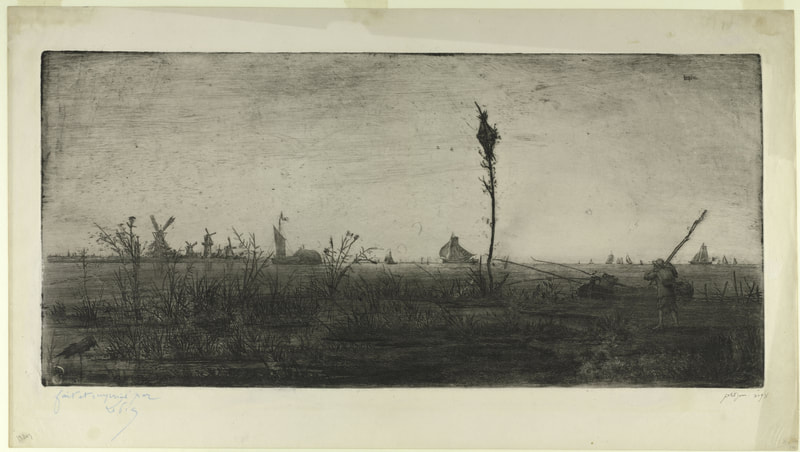

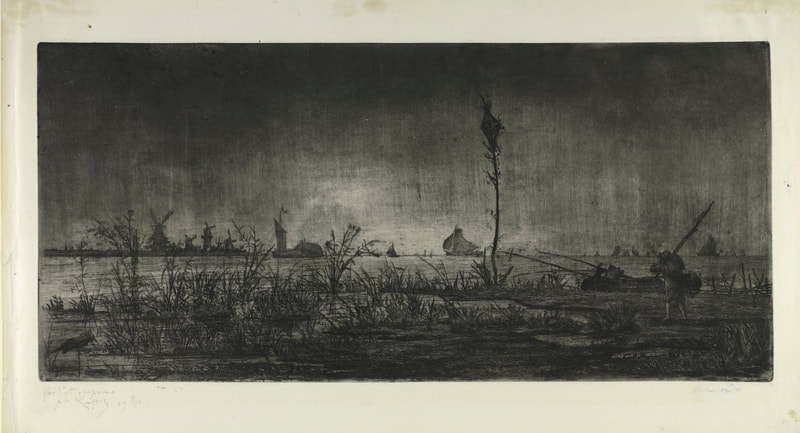

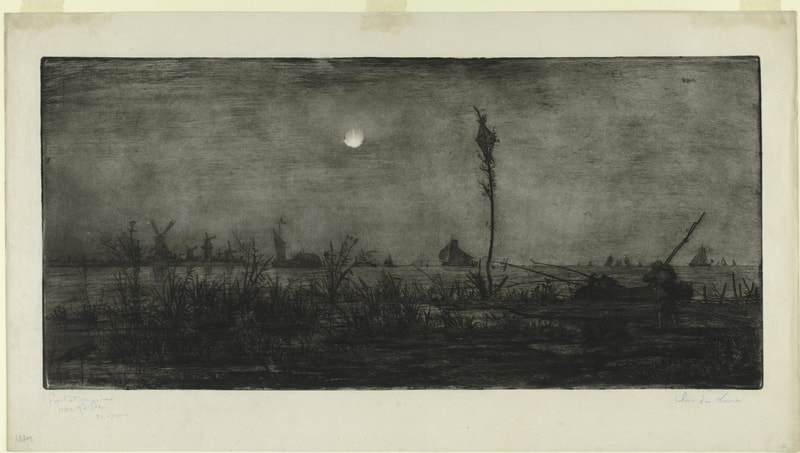

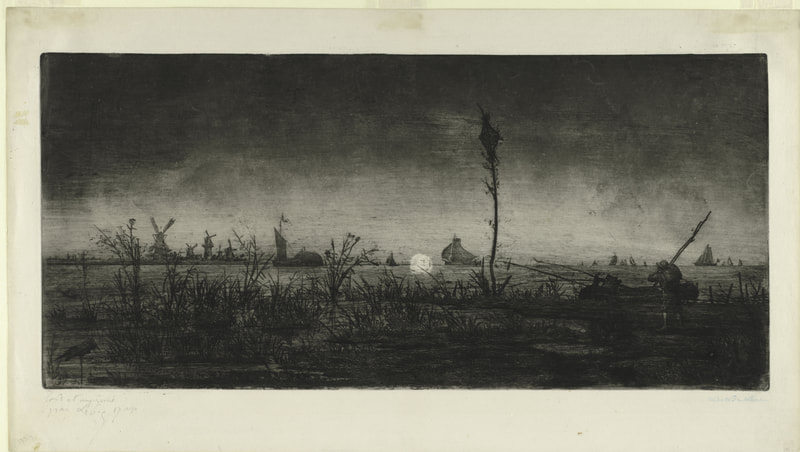

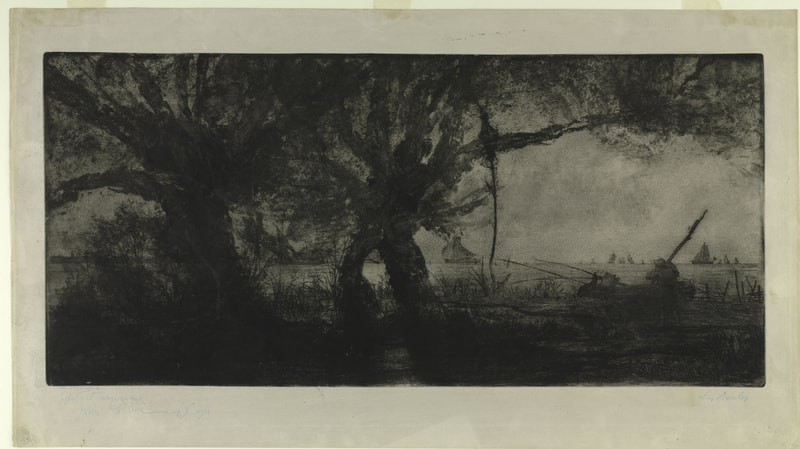

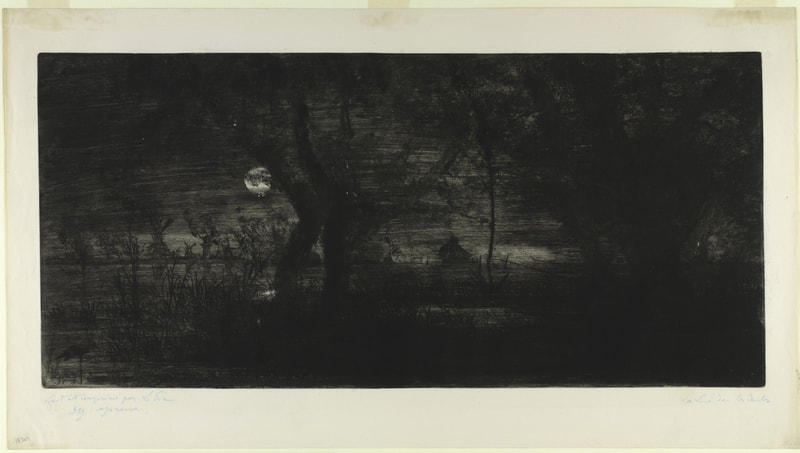

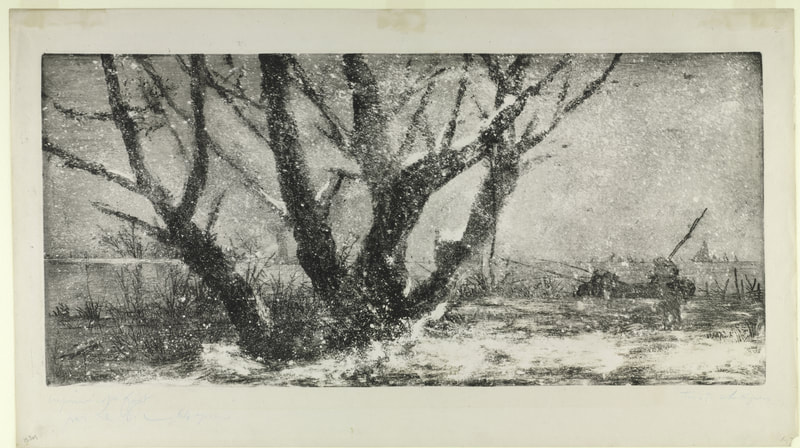

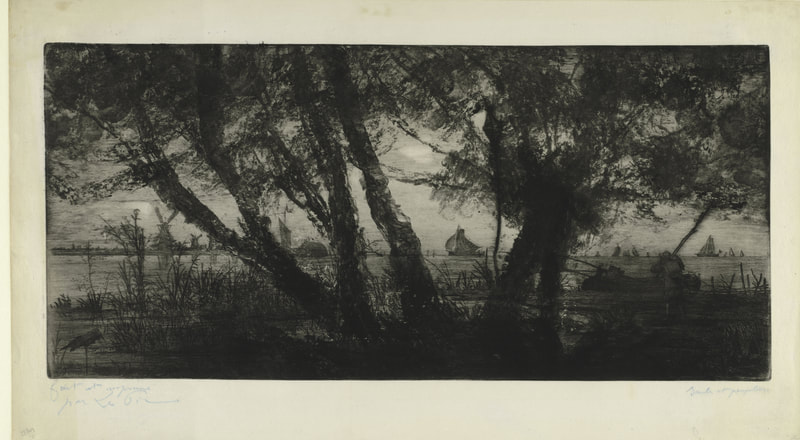

Back in 2011, the museum mounted an exhibition called Print by Print: Series from Dürer to Lichtenstein. It included twenty-nine series of prints—each in its entirety—and looked at seriality and the many reasons artists work this way. You hardly ever get the chance to see complete series of prints framed and on the wall, and the show included series that are heavy hitters in the history of prints. Some of the highlights included Durer’s Apocalypse and Piranesi’s Carceri, Jacques Callot’s Miseries of War, Ed Ruscha’s News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews, and Dues, Sherrie Levine’s Meltdown, and Andrew Raftery’s Real Estate Open House. The exhibition really was a feast for the eyes. But the most remarkable was a group of etchings by Vicomte Ludovic Lepic (French, 1839–1889). I’m gonna guess you’re thinking, who? Lepic was one of the artists who pushed variable wiping to its fullest. These are what we now call monoprints (it’s easy to get confused by the difference between monoprints and monotypes—monoprints start with some image already in the matrix; monotypes are created on a surface that carries no image so each is entirely unique). Twenty impressions of Lepic’s plate were grouped together on the longest wall in the show, each with a different look. They are among the gems of the BMA’s print collection. To be honest, the set of twenty variably wiped etchings doesn’t really qualify as a series. They were not intended to be published as a complete unit. Rather they are a substantial group of prints that are aligned because they use the same matrix in their creation. (Notice my use of the word set to describe them, rather than series. This is bringing out the cataloguer in me.) In fact, I believe Lepic made more versions of this etching, which the BMA does not own. That they don’t strictly fit into the defining principle of the exhibition is not a huge deal, really, especially when they are so instructive, mind-bogglingly beautiful, and can hold any wall anytime anywhere. The etching is a scene on the Scheldt river, which flows northward from France through Belgium and into Holland. First up is an impression wiped tight, meaning no extra ink was left on the surface of the plate. After that follow plates in which ink has been added to the surface to create wholly other compositions: weather effects, different times of day, and the addition of entire trees. They are wonderful examples of how variable wiping can completely alter an image in the best ways. Ludovic Lepic was a French aristocrat who is best known as an etcher and as the subject of several paintings by his good friend, Edgar Degas. Lepic was a painter and sculptor, a costume designer, an amateur archeologist (he founded an archeological museum), a breeder of dogs, an avid sailor, and an equestrian. But for us, his variable etching technique (he called it eau-forte mobile) had a huge impact on modern printmaking. Lepic learned etching from Charles Verlat (1824–1890) and created his first significant etching in 1860. He rapidly became a skilled etcher and in 1862 was invited to join the Société des Aqua-fortistes (The Society of Etchers), formed by art dealer Alfred Cadart (1828-1875) and others to publish original etchings. His etchings were exhibited in annual Salons from 1863 until 1886. Lepic was also involved with the Impressionists. Degas invited him to join with fifteen other artists to form an association to sponsor independent exhibitions, which lead to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. Lepic helped plan this seminal exhibition and showed seven works, watercolors, and etchings. He also showed forty-two works at the 1876 Impressionist exhibition. In the ensuing years he continued to paint, make etchings, create costumes for the Paris opera, and work on his sailboat. He died in 1889. Please meet Ludovic Lepic.

2 Comments

Anita Frichot

9/22/2022 11:10:11 am

Love this article!

Reply

Ann Shafer

9/22/2022 11:30:40 am

Thanks, Anita. The Lepic prints are a wonderment and worth seeking out.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed