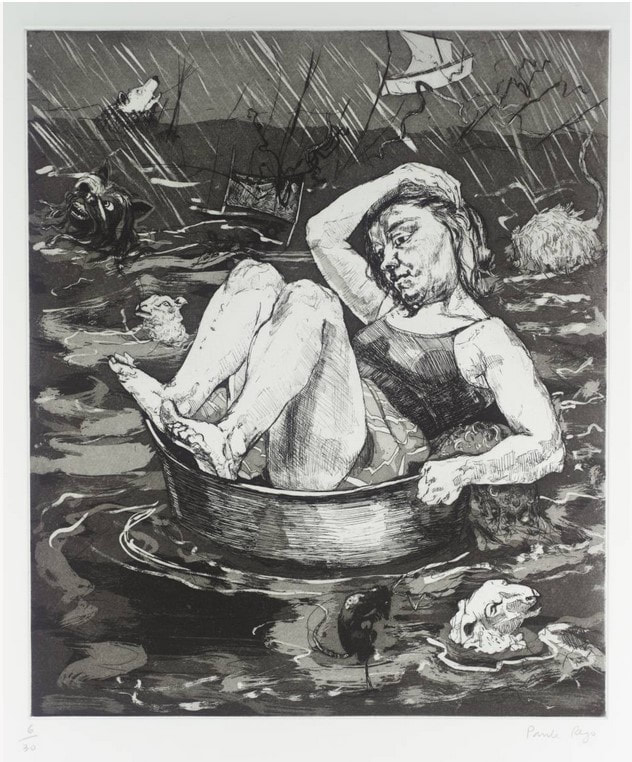

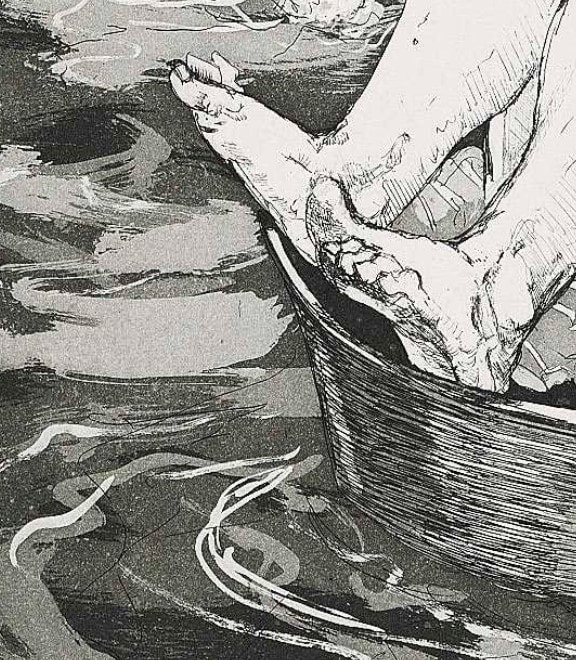

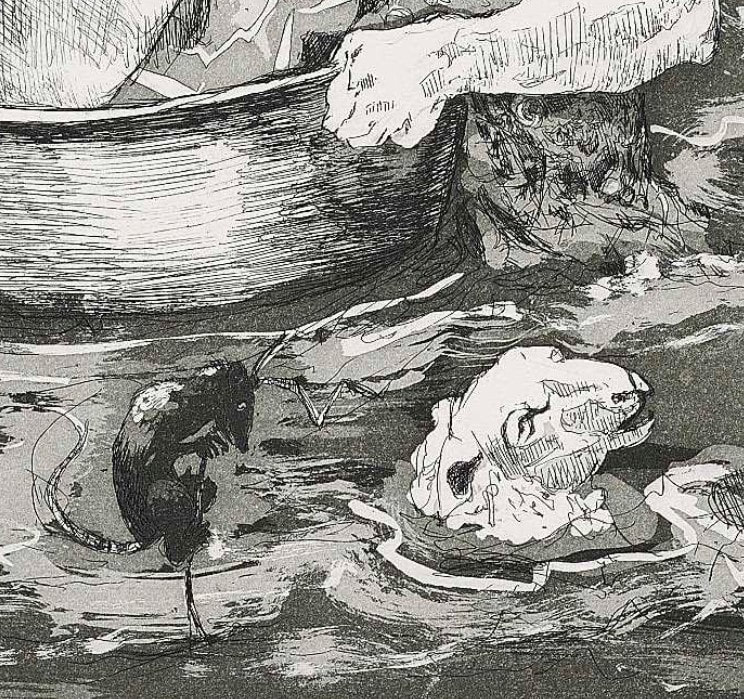

Ann Shafer Here’s one that got away. I always wanted to acquire a print by Paula Rego for the museum’s collection. For some reason I was always drawn to this image from the series The Pendle Witches. Something about the lone figure afloat in an precarious, upturned tub (in my mind it's an umbrella) really spoke to me. Maybe it’s the feeling of being lost in the chaos of the world as it floats by.

This print is from a series that accompany a group of poems by Blake Morrison, which are based on the true story of the Pendle witch trials in England in 1612 (years before the Salem trials). During the trial of multiple alleged witches, the main testimony came from a young girl who was the daughter of one of the accused. There’s more to it, obviously, but the case is held up as an example of the problems that attend depending on one so young, scared, and incapable of understanding the import of their actions. For me, the drifting figure captures the feeling perfectly. I wasn't able to acquire it for the museum, but I still love it. You may be interested in a recent podcast episode from Alan Cristea Gallery featuring Rego and others speaking about her long career and work. An excellent listen. https://cristearoberts.com/podcast/

0 Comments

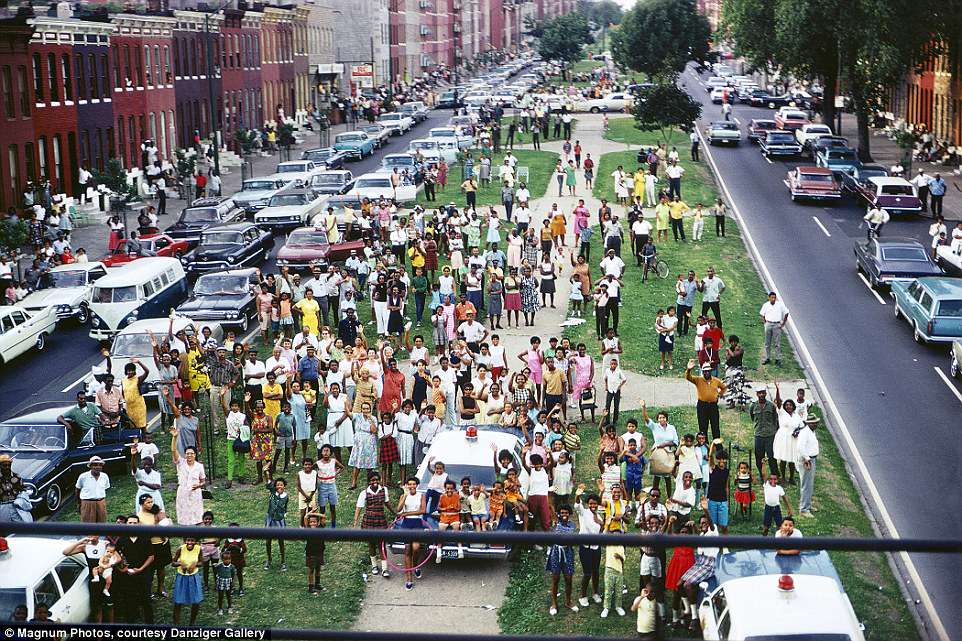

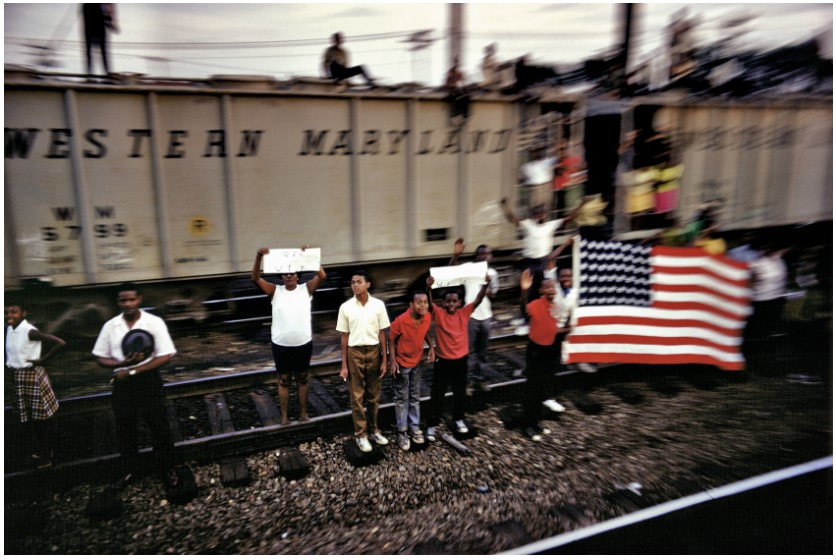

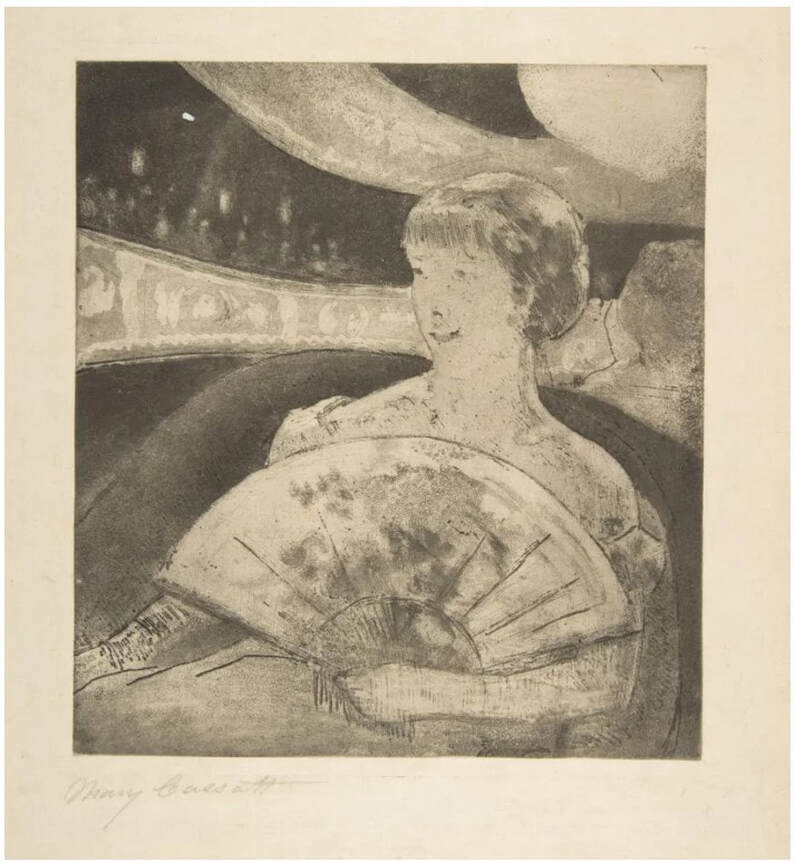

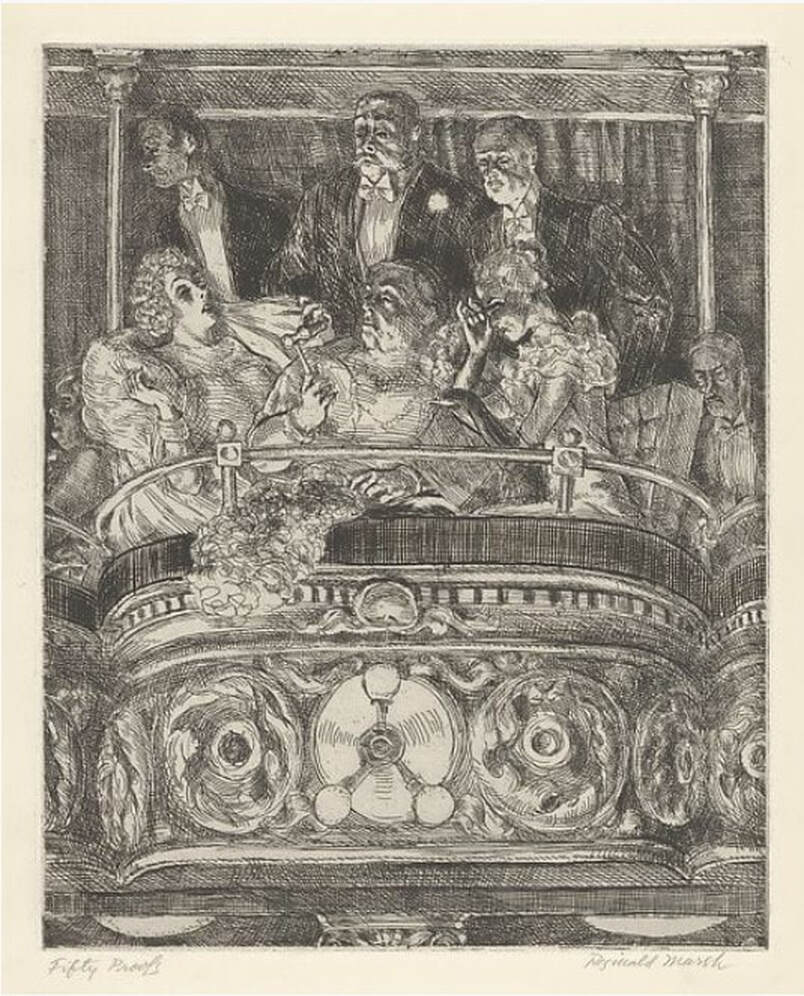

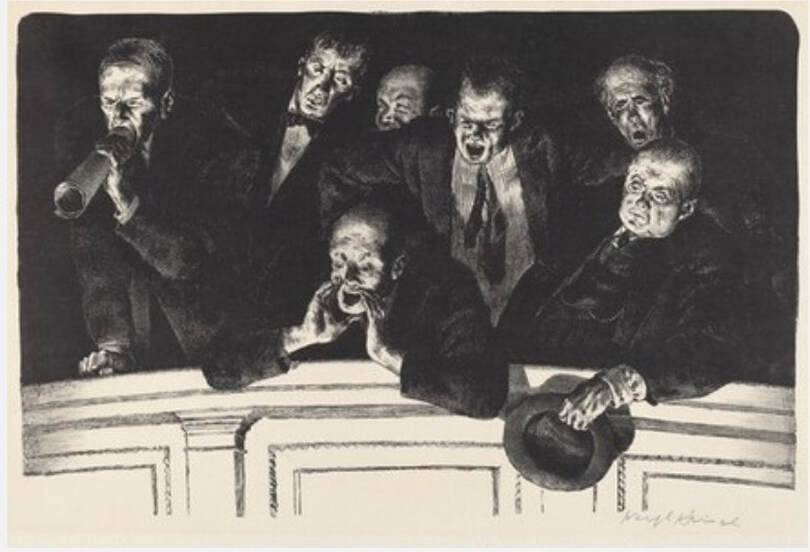

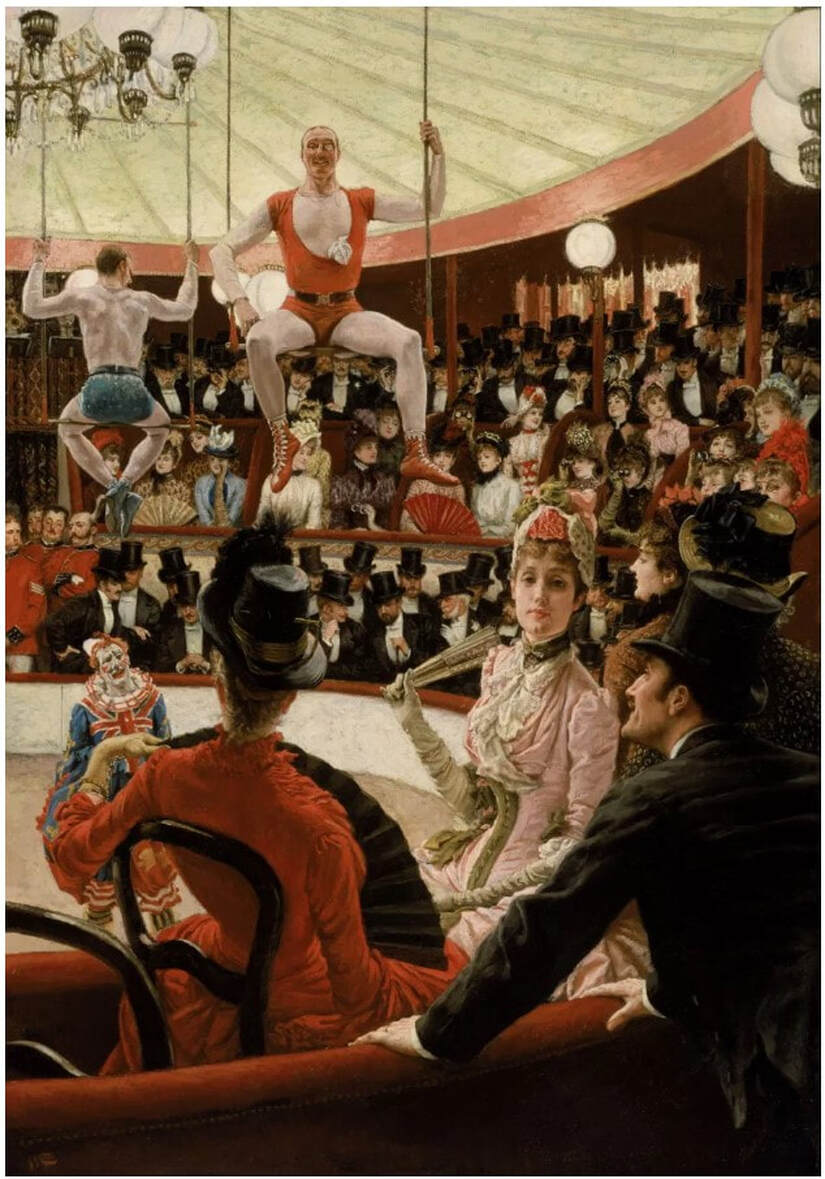

Ann ShaferI always wanted to do an exhibition about the audience. Portraying not the main attraction—the action on stage—but the people who are watching seems ripe for capturing a slice of life. The lookers being looked at flips convention. Voyeurism is a funny thing, alternately creepy and, what’s the opposite of creepy? Oh, pleasant. There are some great prints from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that would fit in this proposed exhibition nicely like Mary Cassatt’s In the Opera Box, 1879, Reginald Marsh’s Box at the Metropolitan, 1934, Joseph Hirsch’s Hecklers, 1943. Of course, there are plenty of paintings portraying audiences, too. My favorite is Tissot’s Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885. Though these images may seem quirky and quaint now, it is possible for an image of this type to cross over into social justice and to capture the zeitgeist. For me, one of the most searing group of images of an audience is Paul Fusco’s series taken in 1968 from the train carrying the body of Robert F. Kennedy from New York to Washington, D.C., for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The photographs capture an emotionally naked populace witnessing the end of optimism in the country. RFK’s assassination followed that of his brother, President Kennedy on November 22, 1963; Malcolm X on February 21, 1965; and Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968. RFK was shot just two months after Dr. King’s death, on June 5, 1968. By then, the country had seen more than its share of sorrow and senseless killing. The photographer, Paul Fusco, died last week, and it reminded me of how powerful the images are still. I marvel at how much emotion is conveyed across decades; they give me chills to this day. It may not surprise you to know that one of the photographs, a shot up North Broadway, just before the train dips underground on its approach into Penn Station in Baltimore, is one that got away. I pitched this photograph some years ago and got enough pushback to return it to the dealer. Part of the issue was that my colleagues weren’t convinced it was Baltimore in the photograph (of course it is), and the other had to do with vintage prints versus later reprints. Many curators seek and prefer to collect vintage prints, meaning the photographs were printed at the time they were shot. The photograph in question was a later printing, and thus was less desirable. I am certain Fusco wasn’t thinking in terms of museum collections in 1968. In fact, as a member of Magnum Photos, an international cooperative agency, he was on assignment for Look magazine, which published two of the photographs in black and white. The series was unknown until Aperture published it in 2008. Hence the later printings. In an earlier post I said I have never forgotten those that got away, and it’s true. To this day, when I see one of these works on the wall in some exhibition, I think “yes, I was right.” A few years after my failed pitch, I saw an exhibition of Fusco’s RFK train pictures at SFMoMA, and there was the North Broadway shot, front and center. Vindication. Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (North Broadway, Baltimore), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Family), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Western Maryland Railroad), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926) In the Opera Box (No. 3), c. 1880 Etching, softground etching, and aquatint Sheet: 357 x 269 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 9/16 in.) Plate: 197 x 178 mm. (7 3/4 x 7 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Imrie de Vegh, 1949, 49.127.1 Reginald Marsh American (1898–1954) Box at the Metropolitan, 1934 Etching and engraving Sheet: 250 x 202 mm. (9 13/16 x 7 15/16 in.) Plate 322 x 252 mm. (12 11/16 x 9 15/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of The Honorable William Benton, 1959, 59.609.15 Joseph Hirsch (American, 1910–1981) The Hecklers, 1943–1944, published 1948 Lithograph Sheet 312 421 mm. (12 5/16 x 16 9/16 in.) Image: 251 x 388 mm. (9 7/8 x 15 ¼ in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2503 James Tissot (1836–1902) Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885 Oil on canvas 147.3 x 101.6 cm. (58 x 40 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 58.45 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed