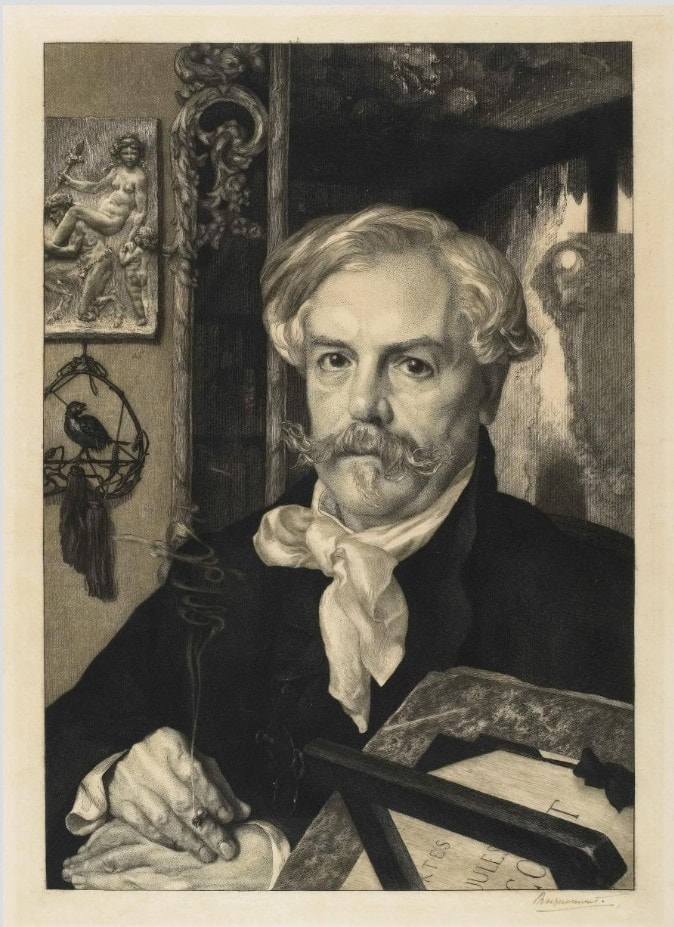

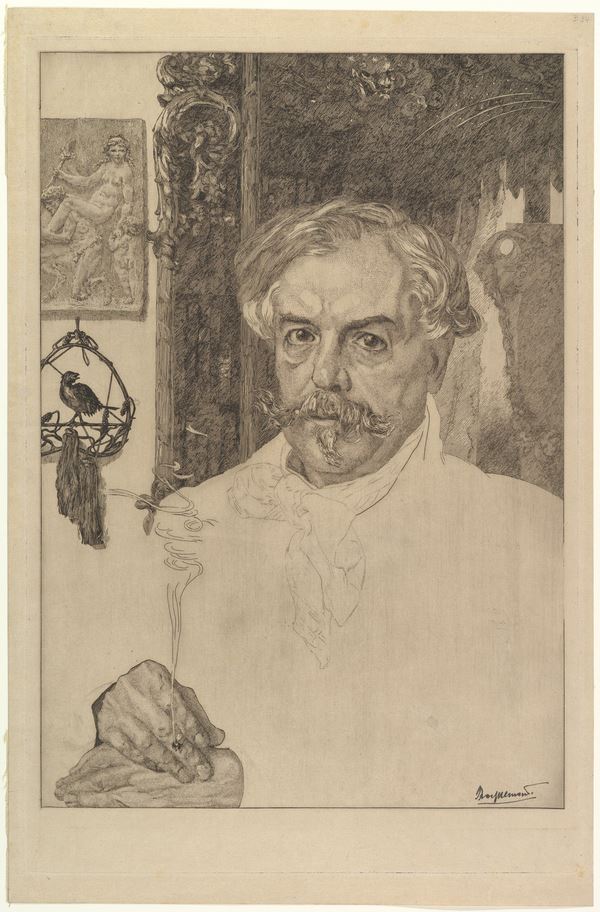

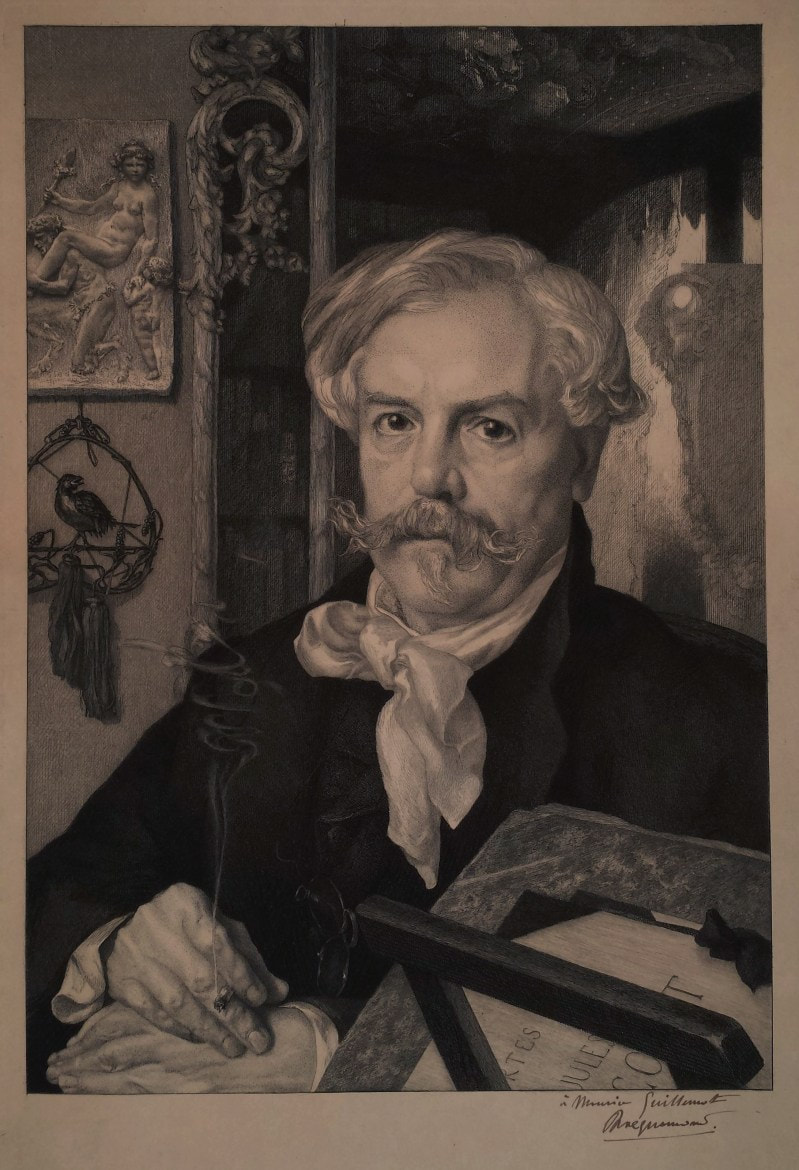

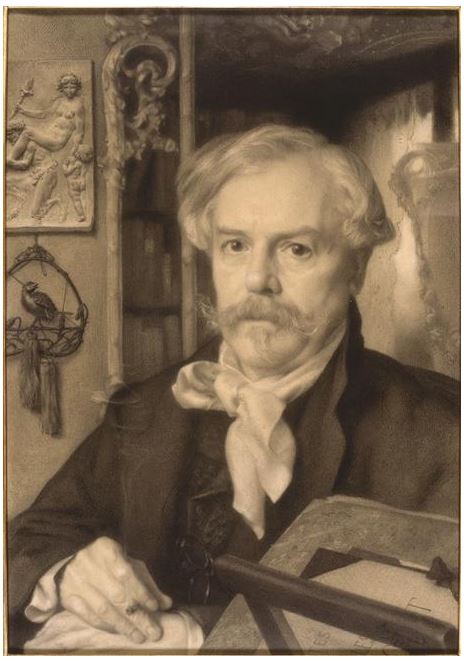

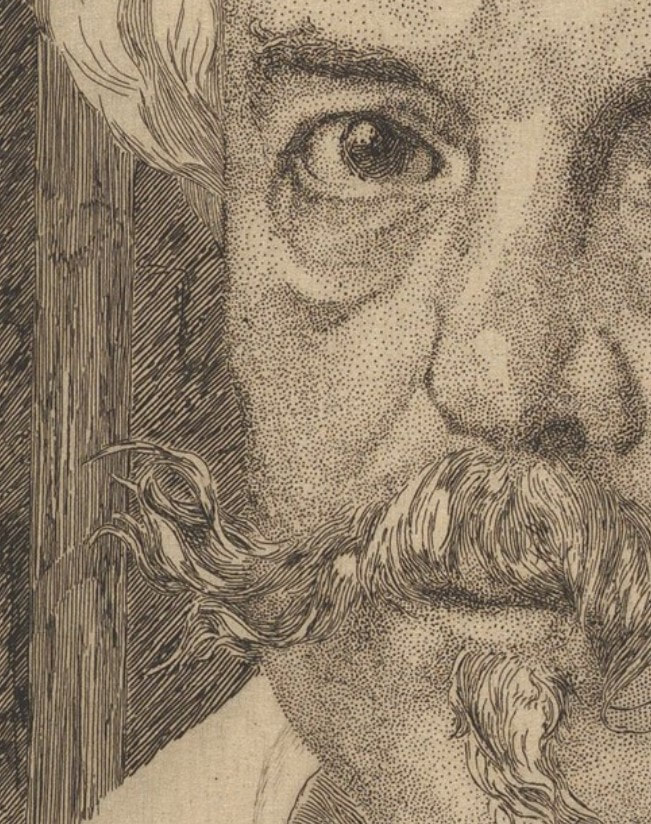

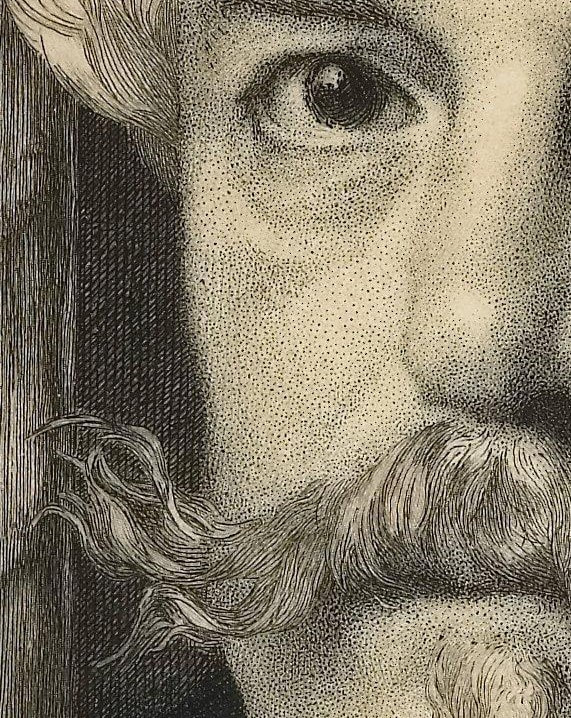

Ann Shafer The museum is fortunate to have two impressions of Félix Bracquemond’s gorgeous portrait of Edmond de Goncourt (one first state and one eighth/final state), and the pair was a permanent fixture on lists for classes studying prints or drawings. Why did I pull the two out constantly? For one thing, it is a kitchen sink etching full of a variety of mark making. Two, having an early state means you can see how and where he started and compare it to the final state. Three, it is a remarkably beautiful and sensitive portrayal of the artist's friend.

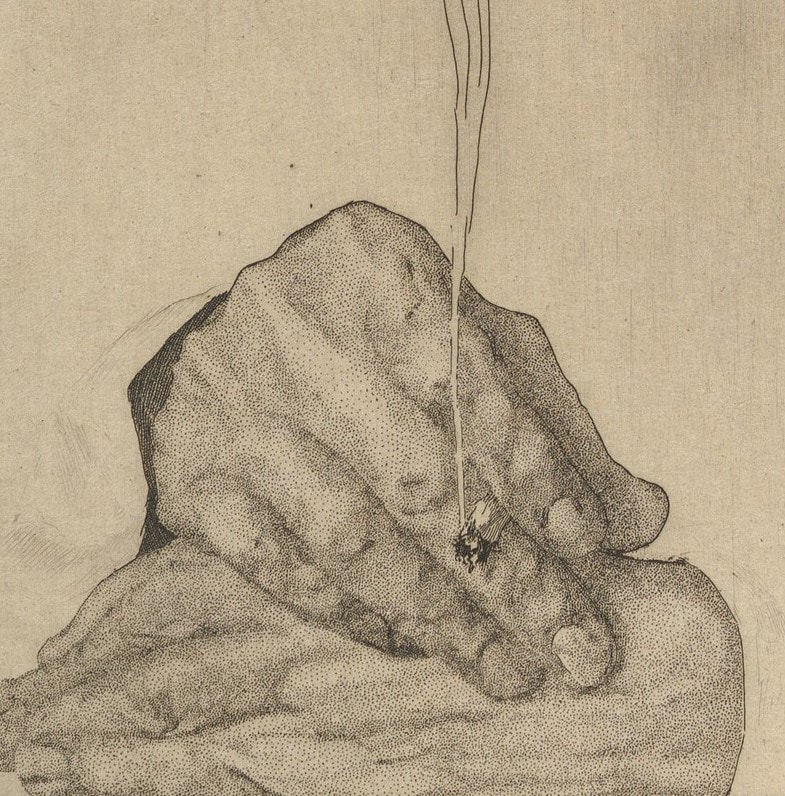

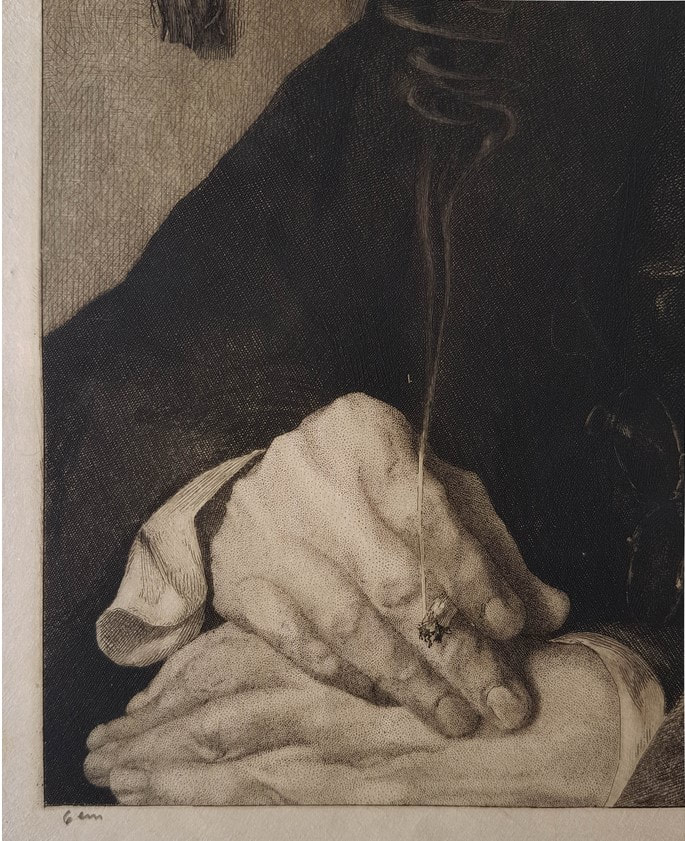

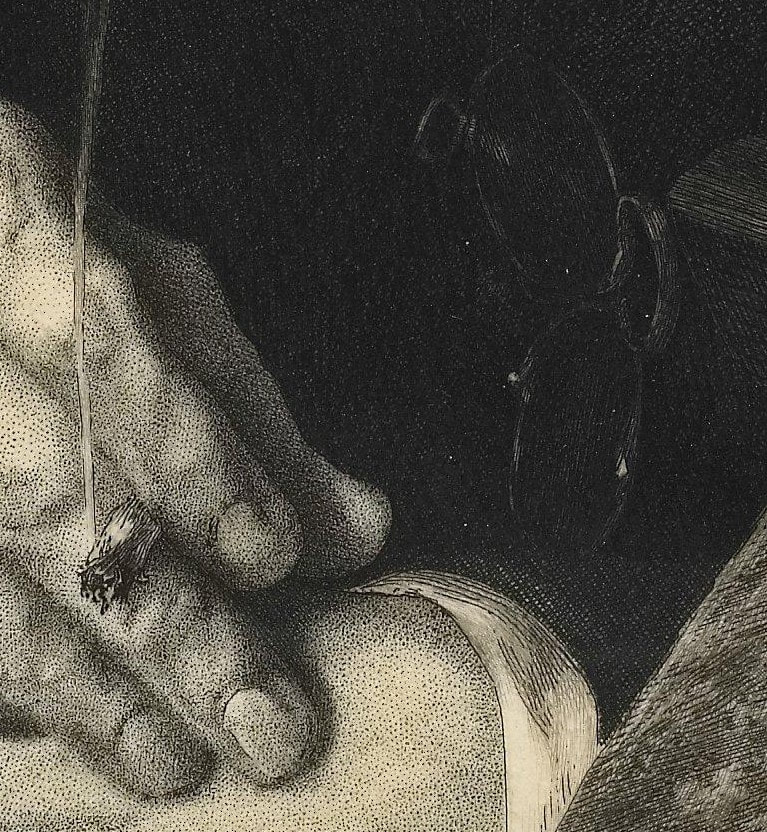

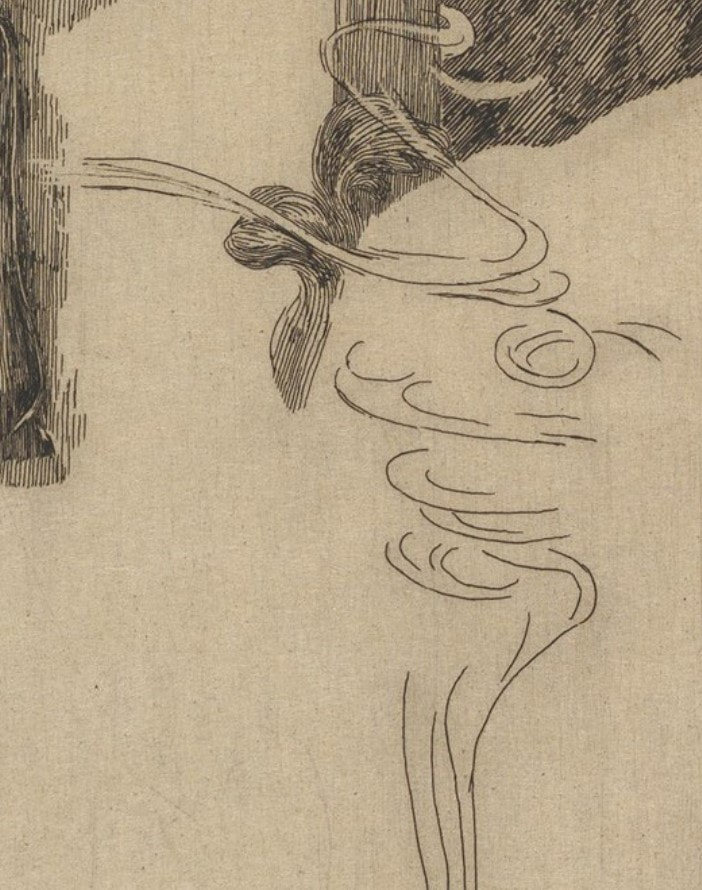

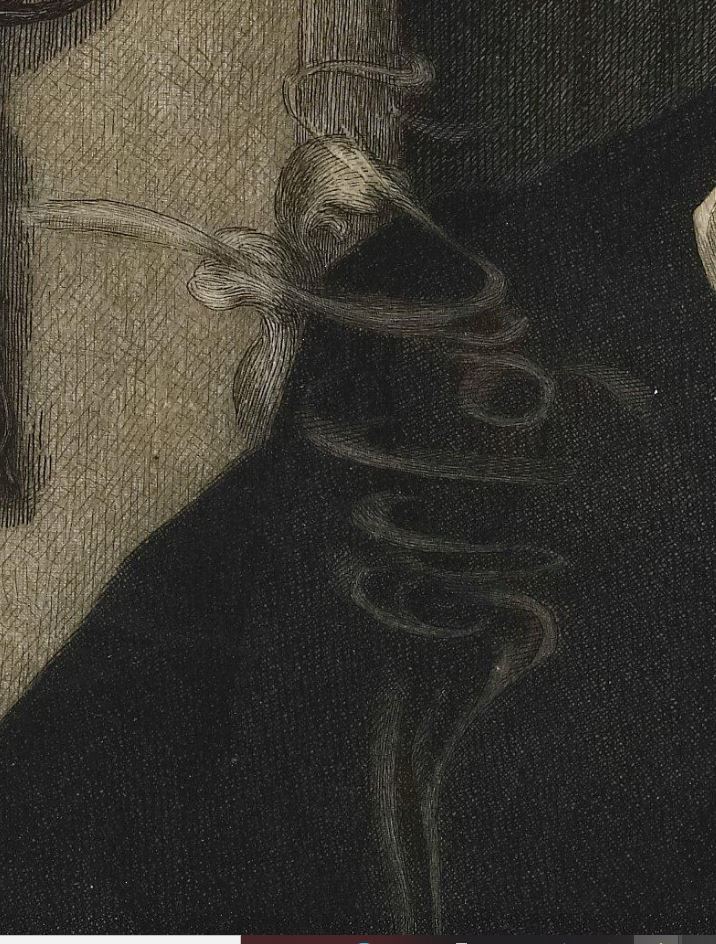

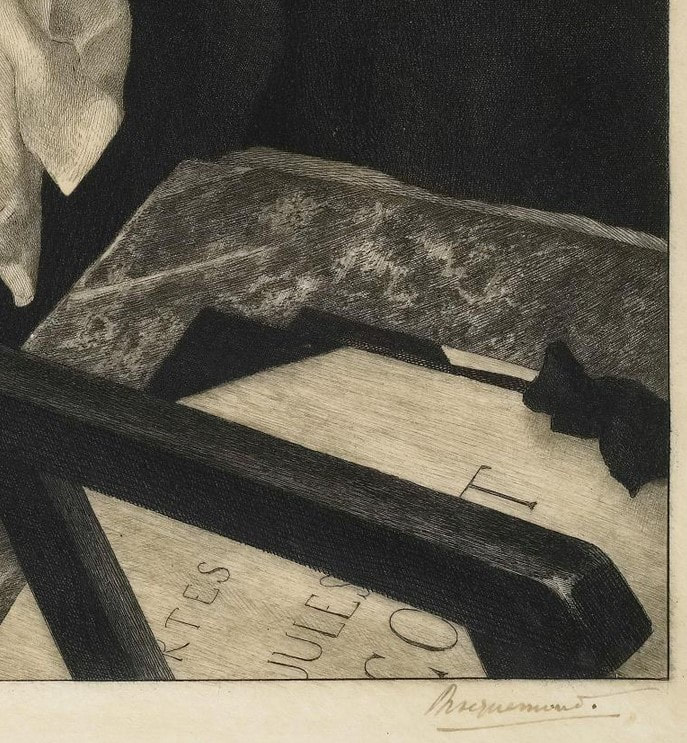

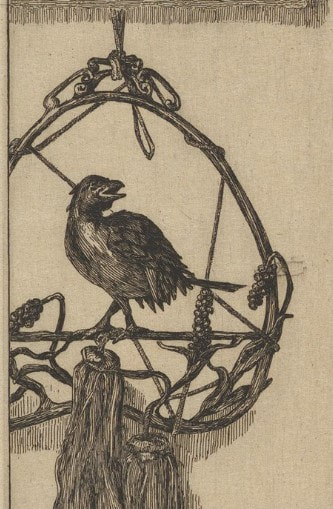

For me, however, the easy sell is the smoke emanating from the cigarette Goncourt holds. I mean, have you ever? In fact it was the smoke in this print that made me start a subject list of all sorts of images. Whenever I was box surfing, I would note works that featured any number of objects or themes: clouds, eyeglasses, monkeys, night scenes, games, sports, city, country, four seasons, seven deadly sins, you get the picture. Trying to draw smoke seems to me to be almost as difficult as portraying water in a vase (see my earlier post about Manet’s Lilacs in a Vase). Bracquemond’s elegant spiral of smoke wafts up from the butt with such elegance. (Please don’t mistake this for an advertisement for smoking—it isn’t.) Bracquemond enjoyed notoriety and success as a printmaker by the time he started work on the etched portrait of Edmond de Goncourt. He had had prints in multiple Salon exhibitions in Paris and his work was included in the first Impressionist show in 1874. He also created designs for dinnerware, was fascinated by Japonisme, and taught etching to many artists including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Théodore Rousseau, Edgar Degas, and Henri Fantin-Latour. Bracquemond was a key figure in the etching revival of the 1850s and 1860s in France. Along with the publisher Alfred Cadart and the printer Auguste Delâtre, he founded La Société des Aquafortistes in 1862. The Société published a monthly portfolio of prints over its five-year existence, including work by the most progressive artists of the time: Edouard Manet, Fantin-Latour, Charles Meryon, James McNeil Whistler, and Bracquemond himself. To say he was in the mix would be an understatement. He made over 900 prints during his lifetime, two favorites of which are worth looking up: Le haut d’un battant de porte (Birds Nailed to a Barn Door), 1852; and The Large Rabbit, 1891. But for me, his Portrait of Edmond de Goncourt, 1881–82, is the pinnacle of his oeuvre. In the portrait, Goncourt is shown surrounded by objects that tell us about him. The most meaningful, perhaps, is the portfolio of prints by his younger brother, Jules de Goncourt, seen at lower right. Jules was an amateur printmaker, but more importantly, together the brothers produced a literary journal that is revered today. It is at once a chronicle of an era, an intimate glimpse into their lives, and the purest expression of a burgeoning modern sensibility preoccupied with sex, art, celebrity, and self-exposure. The Goncourts were known to visit everything from slums and brothels to balls and imperial receptions; they argued about art and politics and were merciless gossips discussing news with and about writers Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, and Emile Zola, as well as artists Edgar Degas, Auguste Rodin, and many others. When Jules (who was ten years younger) suffered a painful and slow death at age thirty-nine from syphilis in 1871, Edmond was at his side. The portfolio in the portrait is a nod to Jules as a beloved brother and close collaborator. Other objects include, at upper left, a relief by the French sculptor Clodion of a frolicking nymph and satyr (mythical woodland creatures) recalling eighteenth-century French art, about which Goncourt was passionate. Below the relief is a bronze ornament with a bird and tassels, which represents Goncourt’s collection of fifteen hundred Japanese objects. On the right is a large vase reflected in a mirror. Apparently, Goncourt’s writing about art often evoked physical sensations such as touch and smell, which Bracquemond suggests with objects, rich fabrics, and that burning cigarette. Bracquemond and Goncourt were friends, which I believe is apparent in the portrait’s attention to detail. It is also one of the largest plates Bracquemond ever worked on, adding to its significance. As an artist paying attention to the new conception of the limited edition, with special proofs, papers, etc., Bracquemond took full advantage. As far as we know, there are probably twenty impressions of state I, six impressions of states II–VII, and 175 impressions of state VIII (twenty-five on vellum and 150 on Japan paper). The images below are of several different impressions of the print, including details of a first state impression from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, a final state impression from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, along with the drawing of the same subject in the collection of the Louvre. Other details come from a variety of collections. Please know these choices are based on the resolution of the online images. (The online images of the Baltimore Museum of Art's impressions are not high enough resolution to reproduce here.) As always, collections are noted in the captions.

1 Comment

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed