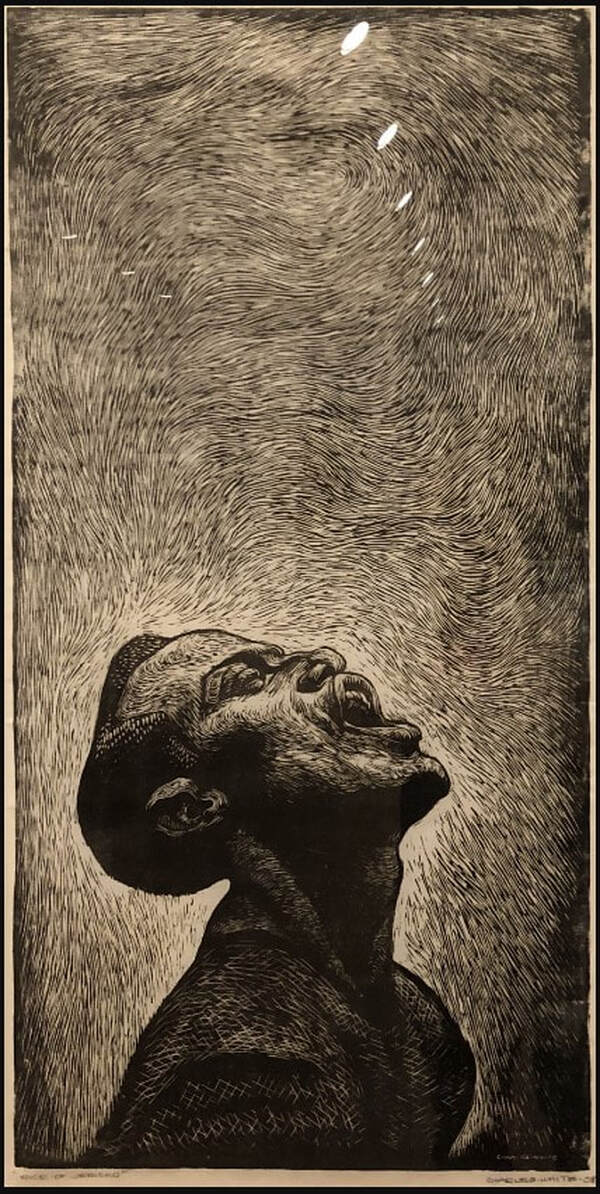

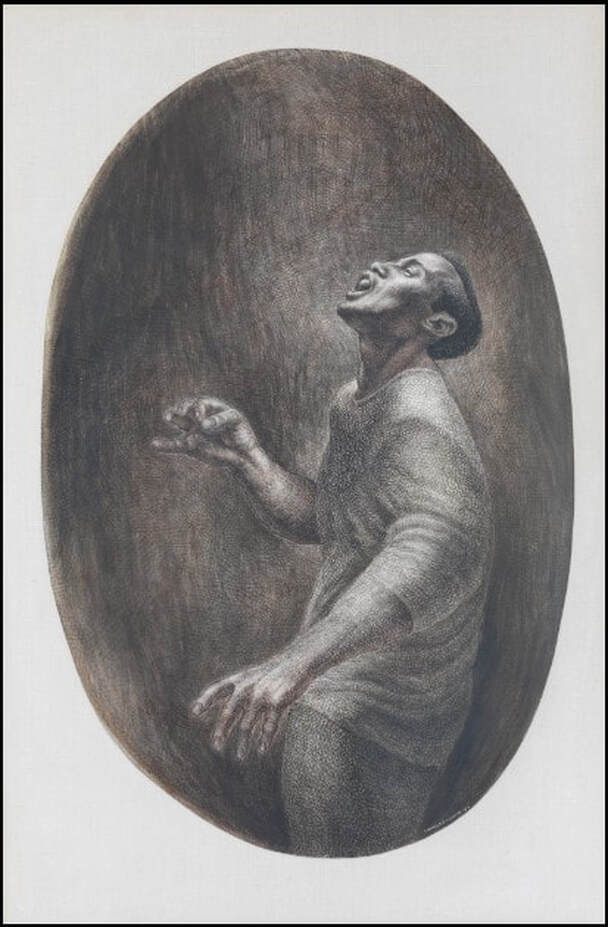

Ann ShaferI wrote recently about jaw-dropping art history moments. For me, there have only been three: Charles Demuth (the church spire behind his house), Edouard Manet (a still life of lilacs in a glass vase), and Velasquez (Las Meninas). Even more rare is getting goosebumps. Today’s post is about possibly my only goosebumpy moment, which has to do with Charles White. White, an African American artist, was the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018–19. Curated by Esther Adler, the show began its run at the Art Institute of Chicago, and finished it at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The BMA has a linoleum cut print by White called Voice of Jericho, 1958. It’s a large print at 39 x 21 inches and shows Harry Belafonte singing. This is a print that I used constantly in the BMA’s studyroom for classes. We would talk about whether the figure was yelling out loud or internally, silently, or if he was singing. And we’d talk and about the portrayal of the sound or silence, which swirls up from the figure to fill more than half the image area. Even if the students were not familiar with Harry Belafonte (he was part of my childhood—one of the first songs I learned on guitar was Jamaica Farewell), the image conveys an immense amount of emotion. And the kids seemed to get it. I made a point of getting to MoMA to see the Charles White exhibition, which was gorgeous. It was during New York Print Week when print curators, dealers, collectors, artists, and publishers descend on the City for four print fairs and a ton of attending programming. As usual, Tru Ludwig was with me. Tru is an artist who also teaches History of Prints at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Voice of Jericho is a staple in that class. I was surprised not to find the BMA print on the walls of the MoMA exhibition—it turned out it had been in Chicago for the first venue, but not included in the second in NY. But the drawing on which it is based was there. (It is owned by Belafonte and his wife.) I had not seen it before and was struck by its gloriousness. But I came away feeling that the print says it better. The drawing includes more of the singer’s figure set on a dark background that lacks the dynamism of the linoleum cut. But in both images Belafonte’s head is cocked back, his mouth open in song, and his neck tensed in the effort. It has always struck me as a posture of potential energy, as if Belafonte is carefully balancing control of performance and his explosive emotions. Here comes the goosebumps part, which were accompanied by welling tears. As part of the MoMA installation, there was a monitor looping video of Harry Belafonte performing the song Bald Headed Woman, which opened his television special, Tonight with Belafonte, in 1959. (It also is on Belafonte’s album Swing Dat Hammer and curiously, was covered by the Kinks and The Who.) A link to the television special is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otw0FtXjOKc&t=507s. It’s the first song Belafonte performs, but doesn’t begin until the 4:40 mark. As Tru and I stood there watching, suddenly the whole thing came together. Belafonte’s performance is mesmerizing and when he reaches for a high note, his head cocks back exactly as White portrayed him in the drawing and print. Goosebumps and tears. Charles White (American, 1918–1979) Voice of Jericho (Folksinger), 1958 Linoleum cut Sheet: 1003 x 540 mm. (39 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.) Image: 917 x 458 mm. (36 1/8 x 18 1/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Friends of Art Fund, 1999.84 Charles White (American, 1918–1979) Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte), 1957 Ink and colored ink with white additions 132 x 865 mm. (52 x 34 in.) Collection Pamela and Harry Belafonte © The Charles White Archives https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otw0FtXjOKc&t=507s

0 Comments

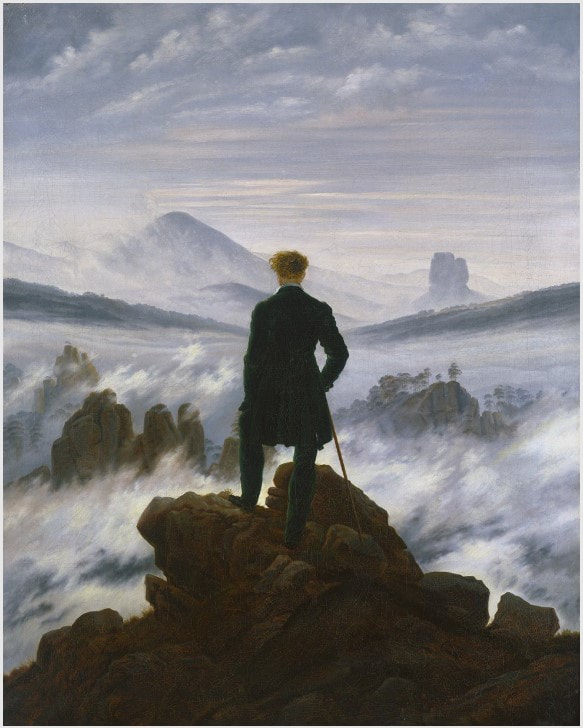

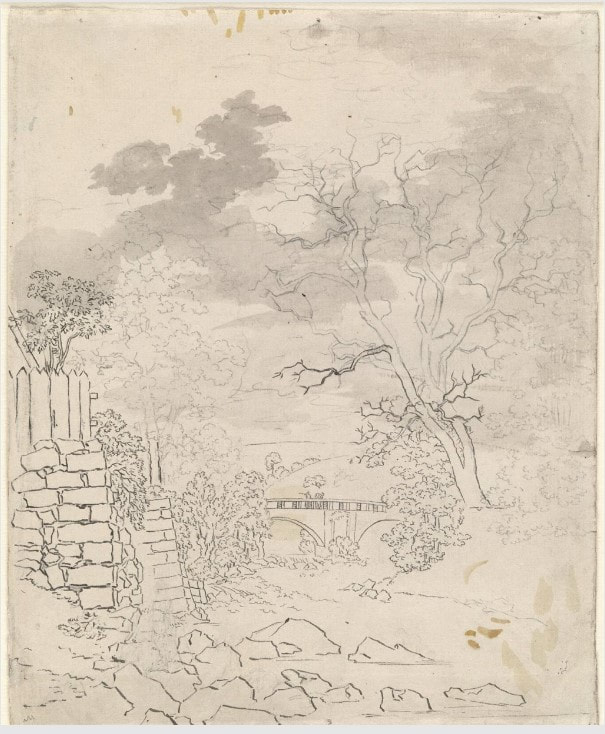

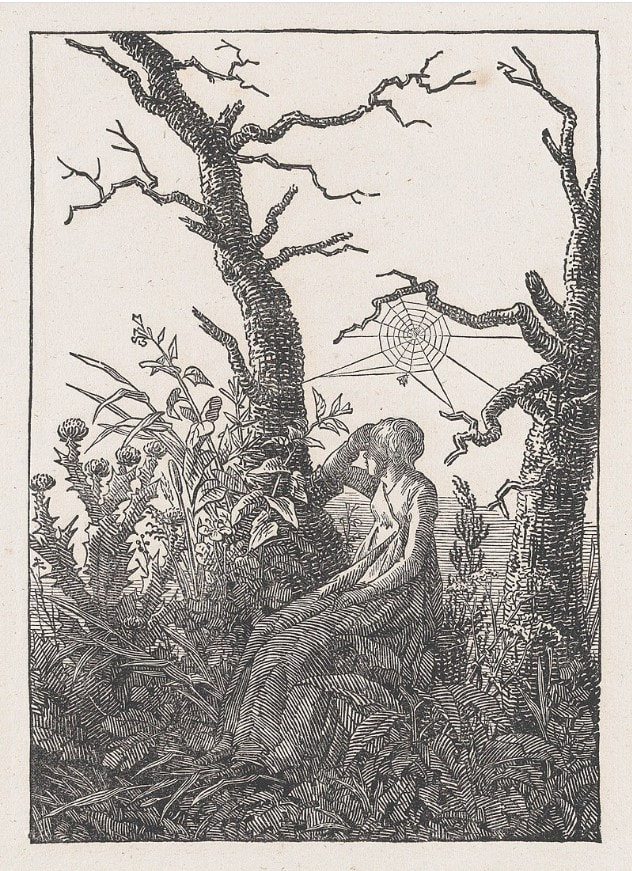

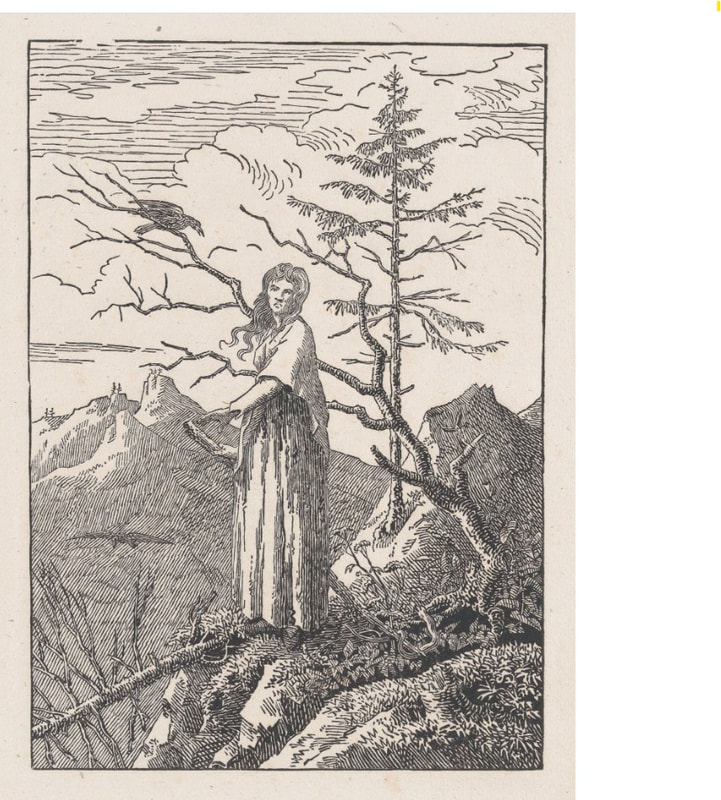

Ann ShaferOn a dreary, rainy Sunday amid a global health and economic crisis, showcasing a melancholic artist seems like just the thing. Caspar David Friedrich, a German artist working at the turn of the nineteenth century, is known for his stark, romantic visions of landscape. In a well-known painting, Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, painted around 1817, he captured the lone figure perched on a rocky outcropping above a vast, open landscape. The composition is constructed of various real elements by Friedrich, but nowhere can one stand on these rocks and see this specific view. But he has constructed the painting beautifully. The figure has his back to us as if he has led us to this spot and we have just arrived. The fog enhances the feeling of solitude. No tree is near him to help ground us and frame the picture. The middle ground mountains roll into the man’s chest bringing us to the heart of the matter (see what I did there?). The final set of mountains intersect with the man’s head, which barely rises above them. This is the sublime at its best. Humans are wired to feel expansive and hopeful at seeing a wide-open prospect such as this. (I’m taking a deep breath as I look at it.) With compositional elements converging in the man’s heart and head, this image speaks directly to the Romantic. For me, there is both a melancholic and hopeful feeling. And maybe that’s Friedrich’s magic: that his paintings can’t help but make us feel something. This painting has stuck with me since Art History 101, although I have never seen it in person. Field trip to Hamburg when this is over and we can travel again? I have always felt German Romanticism had a parallel movement in British landscapes in watercolor and in oil at this same time. I suspect the driving forces between the developments is similar but not identical. (I am no scholar of German Romanticism—please take this with a grain of salt.) But I love Friedrich’s ink wash drawings and watercolors. They are so reminiscent of those by British artists like John Ruskin, but they also can have a starkness and modernity to them that continues to intrigue me. Apparently, Friedrich’s output as an artist was little known during his lifetime and he was “discovered” only at the beginning of the twentieth century. One way an artist might try to enhance his stature was to create and publish prints that could be distributed widely. Friedrich made a pair of prints using his woodworker brother, Christian, as the formschneider (the block cutter). Woman with the Raven on the Abyss and Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, 1803, were entered in an 1804 exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden. I’m not sure about their reception, but it is pretty clear that Christian was not a great woodcutter. When asked by Christian if he would produce further works for transfer to woodcut, the artist declined, writing, "ask another artist." And yet, in Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, I still appreciate the composition: a lone woman sits between two bare trees (blasted tree, anyone?), while above her in the branches is a large spider web. What a creepy, potent, and weird image. It seems like just the kind of quirky print one would find in the Garrett Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art. But alas, it is not in that mammoth collection. For over a decade I kept my eyes open for an impression of the spider’s web print to come on the market (well, I didn’t hunt one down, but it was always in the back of my mind). Feeling certain the museum would never get a hold of a painting or drawing by Friedrich, having one of the prints seemed like a great way to get him into the collection. Plus, the print would have many friends, not the least of which is Dürer’s Melancholia I. Good company, indeed. Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer), c. 1817 Oil on canvas 94.8 cm × 74.8 cm. (37.3 × 29.4 in.) Hamburger Kunsthalle, HK-5161 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) An Owl on a Coffin (Eine Eule auf einem Sarg), 1835–38 Pen and gray ink, brown wash, and graphite 385 x 383 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41119 Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald 1774–1840 Dresden) Gate in the Garden Wall (Pforte in der Gartenmauer), c. 1828 Watercolor over graphite 122 x 185 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41123 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Sea with Rising Sun—Morning of Creation (Meer mit aufgehender Sonne—Schöpfungsmorgen), c. 1826 Brown wash over graphite 187 x 265 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41120 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Bridge over Brook (Bach mit Brücke), c. 1799 Pen and gray ink and gray wash over graphite 270 x 220 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41091 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Hill at Bruchacker near Dresden (Hügel mit Bruchacker bei Dresden), 1824/25 Oil on canvas 22.2 x 30.4 cm Hamburger Kunsthalle, HK-1055 Christian Friedrich (German, 1770–1843) after Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, 1803 Woodcut Image: 170 x 120 mm (6 11/16 x 4 5/8 in.) Sheet: 260 x 193 mm (10 ¼ x 7 5/8 in.) Art Institute of Chicago: Alfred E. Hamill Collection, 1955.1031 Christian Friedrich (German, 1770–1843) after Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Woman with a Raven, 1803 Woodcut Image: 170 x 119 mm. (6 11/16 x 4 11/16 in.) Sheet: 244 x 192 mm. (9 5/8 x 7 9/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund 1927, 27.11.3 Ann ShaferIn 2017, the museum held what is likely to be its last Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair (BCPF). The fair ran at the museum beginning in 1990 (the brainchild of Jay Fisher and Jan Howard), and the proceeds generated enabled the purchase of many prints for the collection. From the final fair, we made a handful of acquisitions, including several that I’ve written about previously. Another of those works is this print by Sascha Braunig executed at Wingate Studio, which is headed by Peter Pettengill. Not only is Peter a consummate printer, but also he and son James and daughter-in-law Alyssa are just about the nicest people you will ever meet. The work they brought to BCPF was always timely, beautifully executed, and exciting. And their sales pitches were also on point. I was honored to include them in the fair over the years.

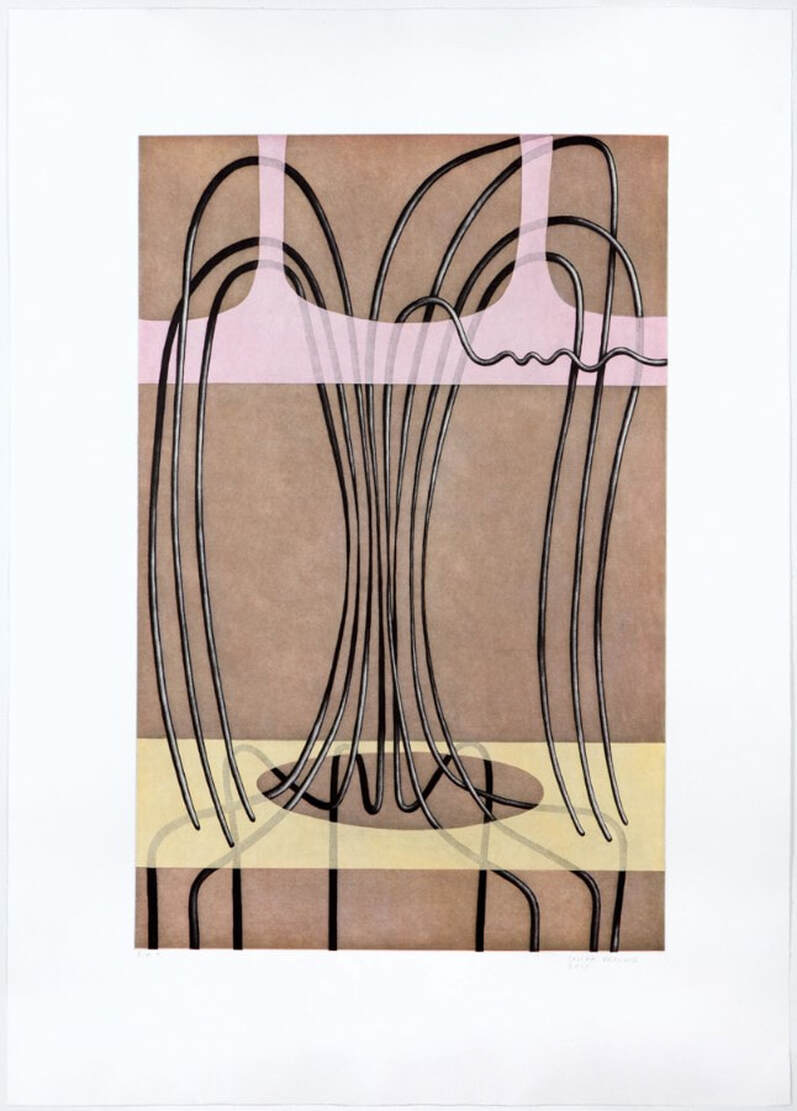

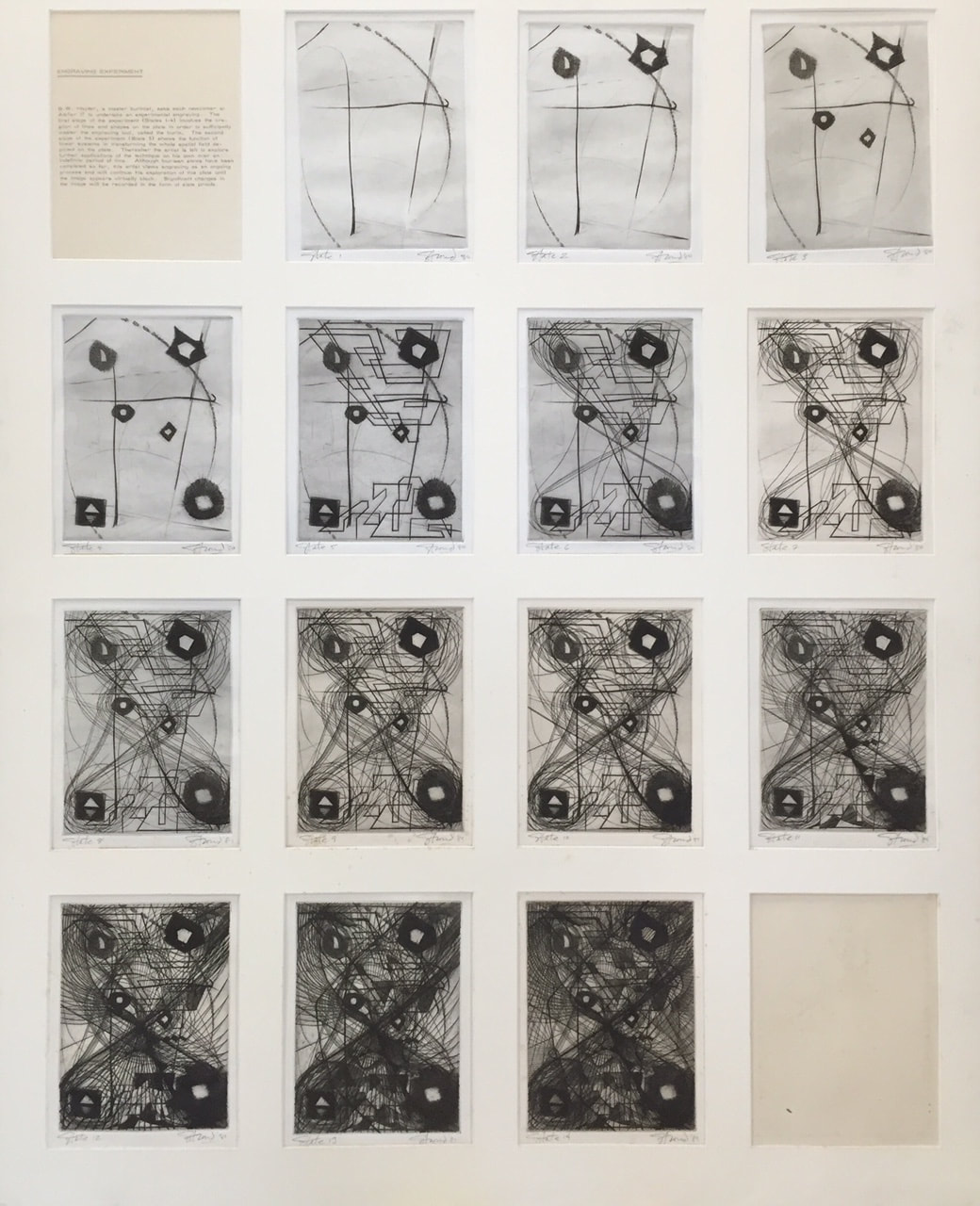

Braunig’s subject is the human body (usually female and usually in paintings and sculpture) portrayed in a reductive but potent manner. In this print, the female figure is formed by metal-looking tubes that mimic a coat rack or corset stays (hence the title). Across the width of the image area is stretched her undergarments, which are delightfully mismatched and totally relatable. But it’s hard to know if the undergarments are effective in any way. They look like they are supporting and shielding the figure but are not really being worn. This confusion fades as one notices that the profile face of the figure is draped over the pink top in a gesture of defeat or resignation. And, just as you begin to make sense of the image, suddenly you notice that the tubes crisscross each other in an impossible way behind her eyes. For me, it comes across as a woman who is dependent on and trying to escape the confines of the stays. The push-pull tension of the piece grows as you spend more and more time engaged with it. In the end, her weariness seems a perfect metaphor for these days of social distancing and this disastrous pandemic. Sascha Braunig (Canadian, born 1983) Printed and published by Wingate Studio Stays, 2016 Four plate aquatint etching with burnishing, soft ground, and sugar lift Sheet: 988 × 711 mm. (38 7/8 × 28 in.) Plate: 733 × 481 mm. (28 7/8 × 18 15/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2017.69 Ann ShaferOur man Hayter was the spiritual epicenter of Atelier 17, which was an important hub for collaboration and experimentation in printmaking. It was his goal that artists would work together toward new discoveries. He downplayed his role as teacher and mentor, although it is clear the workshop’s success owed a tremendous amount to his personal charisma.

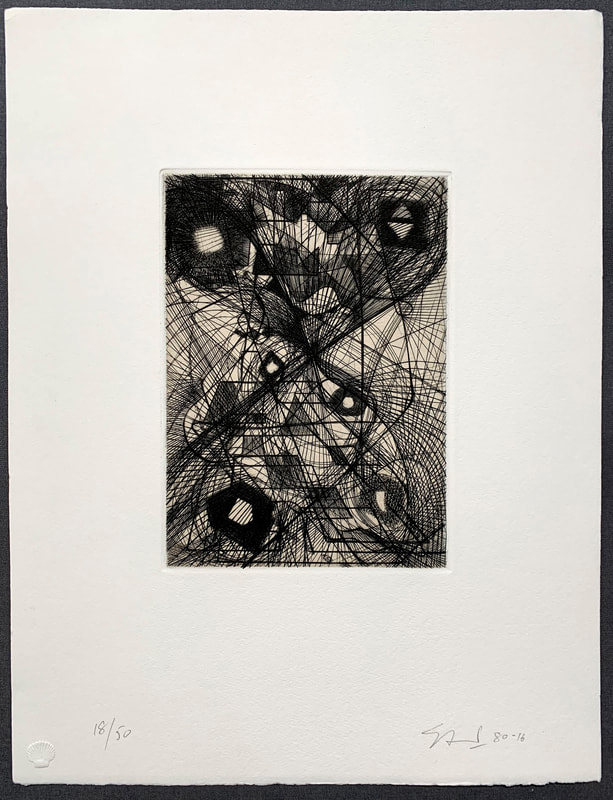

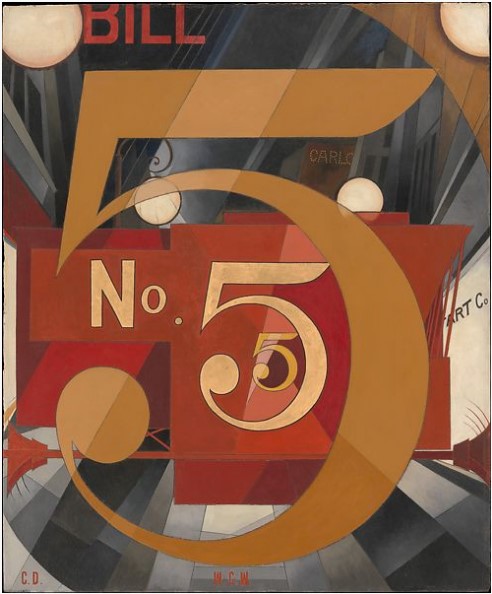

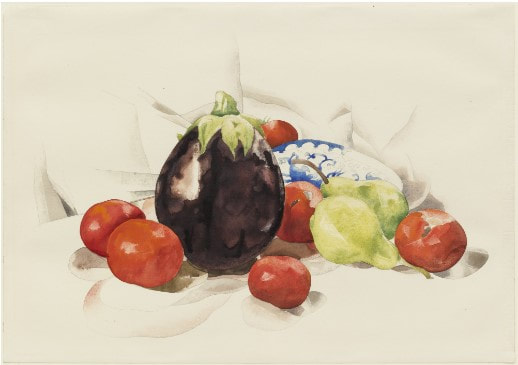

When a new artist arrived at the studio Hayter would put them through their paces before allowing them free access to the equipment. One of the first things was to accomplish a plate of burin studies. Given a copper plate, the nouveau was instructed to make marks without regard to a planned image. This was a chance to become familiar with the technique and process. Hayter encouraged students to free their minds of preconceived imagery and just let the burin go where it might until they had become fully comfortable making marks. Because engraving is a difficult means of making an image—one pushes a diamond-shaped tool through the copper or zinc to create divets that will carry ink—it is important that one is at ease with it prior to investing time and energy in a large print. Hayter, himself, engraved several of these sorts of studies over the course of his career, perhaps in order to go back to basics once in a while. These studies really were supposed to be a freeform exercise tapping into one’s subconscious. He even advocated for creating engraved lines by feel rather than by sight. These ideas can be linked to Hayter’s interest in the surrealist practice of automatic drawing, in which one’s subconscious should be accessed thus producing stronger work. Hayter was active at the Atelier until the end of his life in 1988, meaning scores of artists can claim some time with the master. One such artist is the master printer James Stroud, whose print shop, Center Street Studio, operates outside of Boston. In between his BFA and his MFA, Stroud studied with Hayter at the Atelier in Paris from 1980 to 1981. In the progressive states (he stopped and printed the plate periodically as he added more and more to the composition), the plate is filled with swirling lines that intersect over geometric forms in an orderly yet chaotic way. Stroud reported coming across the plate in his studio in 2014, many years after he engraved it. For fun, he printed a handful of impressions and liked the result. Knowing about the BMA’s planned Hayter exhibition, Stroud not only donated a 2014 impression of the final state, but also the set of earlier states he’d kept all these years. Jim is a superb printer (and artist) and his shop is worth checking out: http://www.centerstreetstudio.com/. James Stroud (American, born 1958) Burin Studies (state 1-14 and final), 1980 Engraving Sheet (each): 250 × 205 mm. (9 13/16 × 8 1/16 in.) Plate (each): 184 × 138 mm. (7 1/4 × 5 7/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of the Artist, 2016.140.1–14 and 2014.100 Ann ShaferI wrote my senior thesis on my second and more abiding love, Charles Demuth (DEE-muth, not deMOOTH). I focused on several groups of his watercolors featuring figures: circus and vaudeville acts, literary illustrations for Henry James and the like, and erotic-ish scenes including sailors dancing, lolling on the beach, jazz clubs, and Turkish baths. I don’t think I have my copy of that paper anymore, which is just as well. Not that the watercolors aren’t great, they are, but that my writing about them was surely riddled with holes. Demuth remains a favorite because not only are the figural watercolors awesome, his still lifes in watercolor are breathtaking and his output in painting is stunning. Two of my favorite paintings are I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928, and My Egypt, 1927, which I saw nearly every day when I worked at the Whitney right out of college.

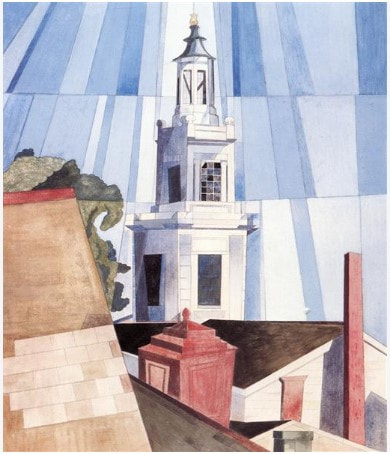

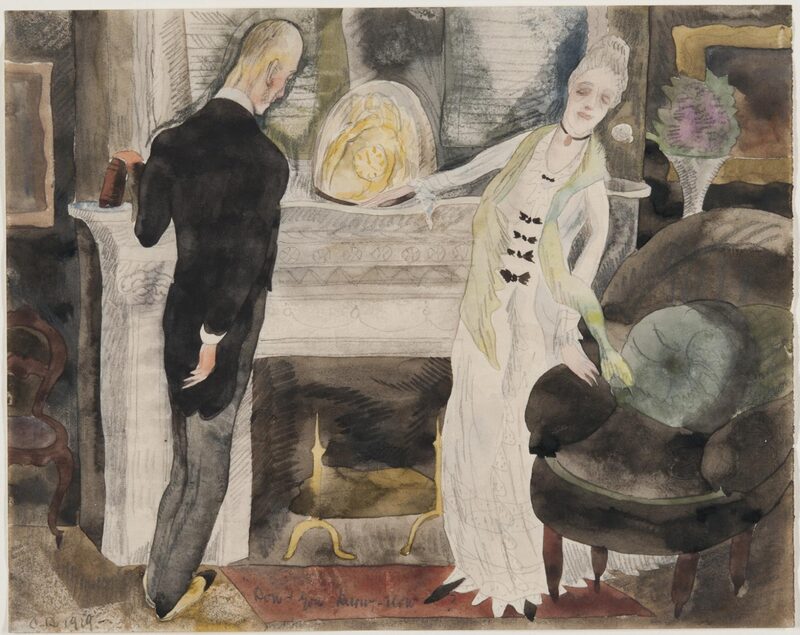

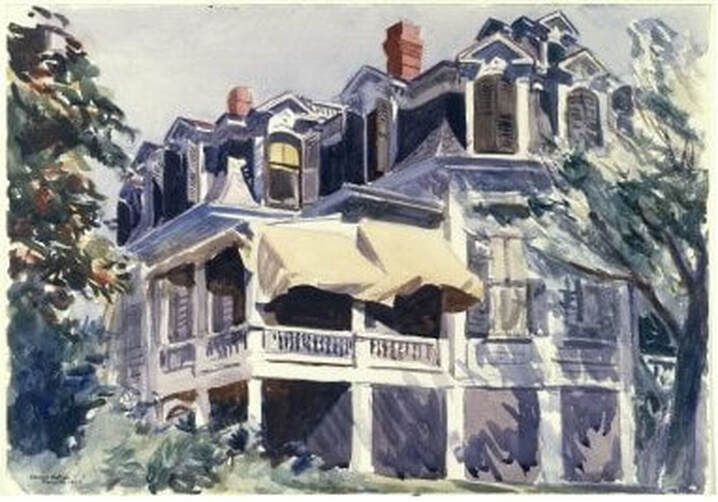

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold is one of Demuth’s eight portraits painted in tribute to various American writers, artists, and performers. None are physical likenesses, but rather they show imagery that evokes the person and their work. This one is a tribute to William Carlos Williams who was a friend, poet, and his physician. (Demuth died at age 51 due to complications from diabetes. He was one of the earliest patients to give himself insulin shots—a brand new treatment.) The title of Demuth’s painting is taken from Williams’ poem that describes the sights and sounds of a firetruck speeding down a New York City Avenue: Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city It always makes me smile when I happen upon I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was more fortunate to be able to look at My Egypt every day for two plus years at the Whitney Museum of American Art (back when it was in the Breuer building at Madison and 75th Street). Its title gives a pretty substantial hint as to what it’s about: our grain elevators, water towers, and factories stand as monuments to America’s achievements in industry in much the same way the pyramids glorify the pharaohs in ancient Egypt. One could also guess that Demuth is likening the dehumanizing of the labor force in big industry of the 1920s to the slaves that built the pyramids. In addition to factories and grain elevators, Demuth painted church spires, which often loom up over the viewer. Sometimes it appears that an artist’s imagination has run away with them, that the scene portrayed couldn’t possibly exist in real life, and I frequently wonder how they conceived of such a view. For instance, Thomas Moran’s paintings of Yellowstone National Park look like confections in yellow and pink, but parts of the park really are those same colors. Demuth’s point of view became very clear to me on a visit to the Demuth Museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The museum includes the family home and the tobacco shop next door, which are in the middle of downtown. I made a pilgrimage there one January only to discover the museum is shuttered in the winter (should have checked the internet). Disappointed but not daunted, I knew there was a garden behind the building where Demuth had spent much of his young life painting the flowers his mother grew due to his frailty (severe diabetes). I made my way down the tiny passthrough between the buildings and emerged into a lovely, small, brick-lined garden. Then I looked up and my jaw dropped. Looming over the garden courtyard is the giant church steeple of Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, which is directly behind the house. It was as if one of his paintings, like The Tower, 1920, came to life, after which his style and acute angles made so much sense. That was one of only three times that my jaw has dropped for art: the first was in a nineteenth-century art class in college when a slide (yes, slide) of a Manet painting of lilacs in a glass vase popped up, the second was while standing in front of Velasquez’s Las Meninas at the Prado. While Demuth’s paintings are amazing, I have, no surprise, a soft spot for his watercolors. The still lifes are worth checking out. He has such a delicate and deft touch, he’s unafraid of leaving white space, and I love his use of salt and small squares of blotter paper to gain that mottled texture and those sharp edges. I could look at the fruit and flower watercolors all day long. The figural watercolors are less easy to love, but they are an interesting facet of his work. The illustrations for various works of literature—he seemed particularly keen on Henry James—weren’t commissioned to illustrate published works, rather, they were personal, just for him. The circus performers and vaudeville acts are quirky and fun. And his scenes of sailors partially nude on the beach or in dance halls, where two men dancing with women gaze longingly at each other, or a self-portrait at the Lafayette bathhouse reveal he was an openly gay man partaking in the burgeoning underground gay subculture in post-World War I New York. These erotic works were not for public consumption, but in subsequent years they have offered inspiration to artists working with similar themes. Only Hayter has eclipsed my deep and abiding love for Demuth. No, actually, I find Demuth’s work more beautiful and personally satisfying. There is just so much more to discover with Hayter. Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928 Oil, graphite, ink, gold leaf on paperboard (Upson board) 35 1/2 x 30 in. (90.2 x 76.2 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949, 49.59.1 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) My Egypt, 1927 Oil, fabricated chalk, and graphite on composition board 35 15/16 x 30 in. (91.3 x 76.2 cm.) Whitney Museum of American Art: Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 31.172 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) The Tower, 1920 Tempera on pasteboard 23 1/4 x 19 1/2 in. (591 x 495 cm.) The Columbus Museum of Art: Gift of Ferdinand Howald, 1931.146 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) The Revelation Comes to May Bartram in Her Dressing Room, 1919 Illustration for the short story "The Beast in the Jungle," by Henry James Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 203 x 257 mm. (8 x 10 1/8 in.) Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Frank and Alice Osborn, 1966, 1966-68-6 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) Eggplant and Tomatoes, 1926 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 358 x 509 mm. (14 1/8 x 20 in.) Museum of Modern Art: The Philip L. Goodwin Collection, 99.1958 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) Dancing Sailors, 1918 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 204 x 257 mm. (8 1/16 x 10 1/8 in.) Cleveland Museum of Art: Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1980.9 Ann ShaferEdward Hopper, the original social distancer. Seems like the perfect time to write about the first artist I studied in depth. Back in college, I was aiming at American paintings, mainly of the first half of the twentieth century. That I ended up a print person surprises me still since I backed into their study unintentionally. I wrote my junior thesis on Edward Hopper and his depiction of women in paintings. (Tip of the hat to my brother Ren MacNary, who helped me type it--on a typewriter.) I think I tried to approach it with a feminist lens but really, I was writing from my gut. I haven’t looked back at it in years; I don’t even know if I still have a copy, which is just as well. New York Movie, 1939, is one of my favorite Hopper paintings featuring a lone figure. I’m fascinated by artists’ depictions of the audience and the loneliness that can be felt in a room full of people. Hopper’s woman is a great example of the theme of alone in a crowd.

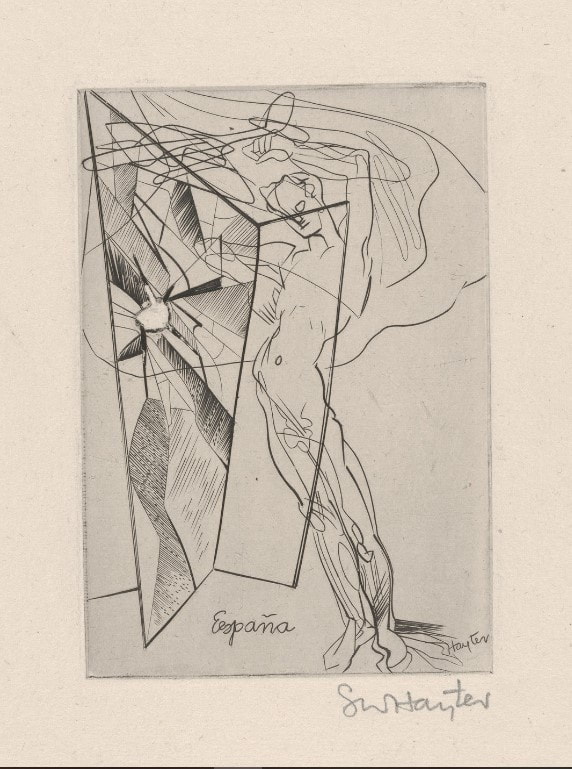

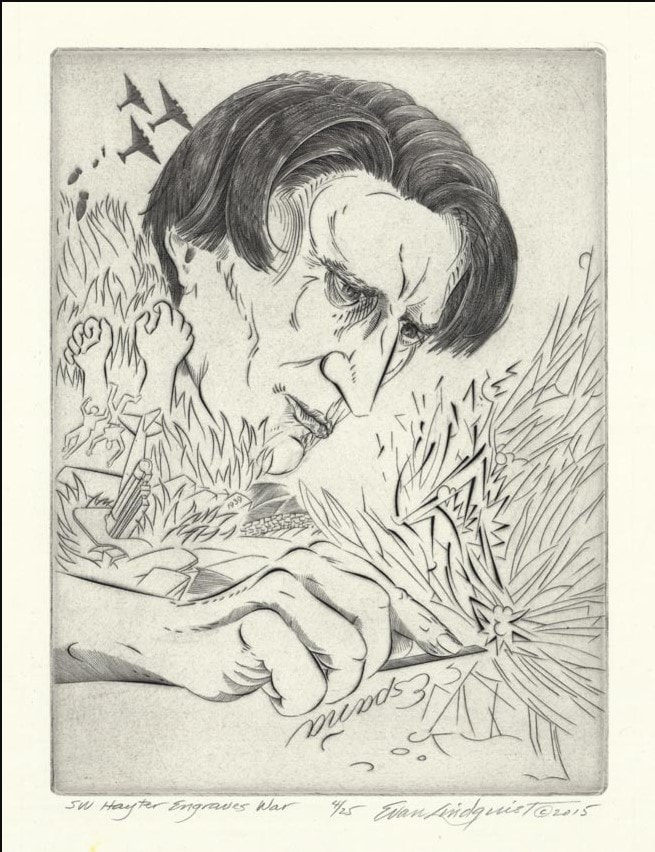

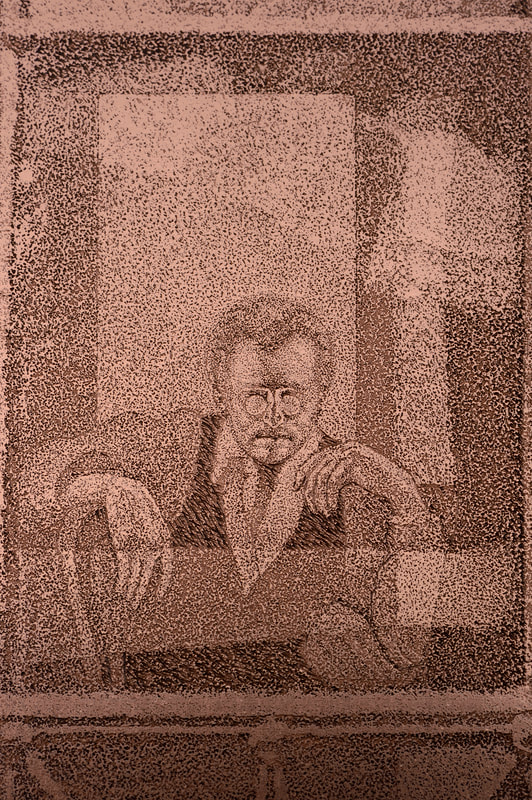

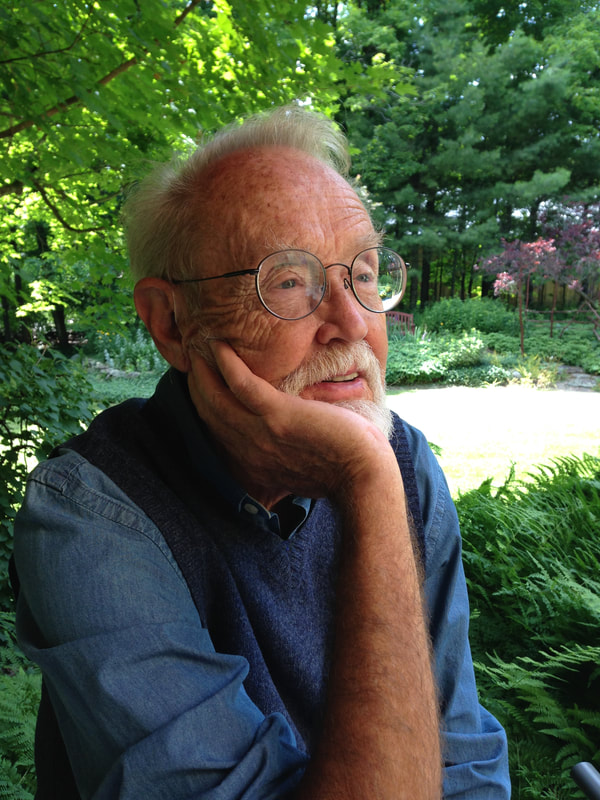

Like so many artists, Hopper also made work in other media as a regular part of his practice. I have a soft spot in my heart for good watercolors (I dabble, and my mother was pretty darn good at them) and Hopper painted some real beauties like The Mansard Roof, 1923. I love that he portrays Victorian domestic architecture (considered out of fashion at the time) rather than the picturesque harbor of the fishing village of Gloucester, Massachusetts, which was the focus of other artists working there in the twenties. Painted on an angle and from below, the house’s billowing yellow awnings dominate. While this is an accurate representation of the house, really it is an exercise in light and shadow. When he painted this house in 1923, Hopper was spending the first of six summers in Gloucester, was trying out watercolor for the first time, and had just met his soon-to-be-wife, Josephine Nivinson. In addition, after not selling any work for the prior ten years, this watercolor was included in an exhibition at, and subsequently purchased for the collection of, the Brooklyn Museum. Not bad for a first stab at the notoriously difficult medium of watercolor. His facility with the brush reminds me of another watercolorist who seemed to be able to whip off a gorgeous work in no time, John Singer Sargent. Because of my own experience and love of watercolors, landing a first job as a curator in a works on paper department represented a shift, but a good one. It wasn’t until much later that I made the final shift to loving prints, which are a tough sell to the public. The barriers to entry are many: the technical information is challenging and complicated, the concept of multiples is confusing, and what does “original” mean anyway. But, once we get people past a certain point, they’re in. Hence my self-identification as a print evangelist. My transition to the dark side was completed under the expert eye of Tru Ludwig. We’ve looked at thousands of prints together and he is my rock. Prior to painting in watercolor in Gloucester, Hopper began making etchings in 1915. He is said to have taught himself, but there is some thought that he learned some of the technical ins and outs from Martin Lewis (more on him in a future post). Of his seventy-some etchings (only 28 were published), my favorite is American Landscape, 1920. Formally, it is such an odd composition with its horizontality and the main subjects—a group of cows trundling over railroad tracks—occupying the lower half of the composition. Only the top of the house rises into the sky. Perhaps we could read into it that Hopper’s prevailing theme of loneliness is personified in the house that is cut off from society by the railroad tracks. Perhaps the cows are the farmer’s only link to the outside world. Who knows? But I do know that to our twenty-first century eyes, the composition looks like a film still: dramatic angle, stark lighting, mundane action portending the future. It all seems apropos in these times of pandemics, quarantines, and social distancing. Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) New York Movie, 1939 Oil on canvas 81.9 x 101.9 cm (32 1/4 x 40 1/8 in.) Museum of Modern Art, 396.1941 Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967) The Mansard Roof, 1923. Watercolor over graphite 352 x 508 mm. (13 7/8 x 20 in.) Brooklyn Museum: Museum Collection Fund, 23.100 Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) American Landscape, 1920 Etching Sheet: 326 x 442 mm. (12 13/16 x 17 3/8 in.) Plate: 185 x 313 mm. (7 5/16 x 12 5/16 in.) National Gallery of Art: Rosenwald Collection, 1949.5.70 Ann ShaferEngraving was Hayter’s first love. He wanted to reintroduce it as a tool for what he called “original expression,” which basically means for one’s own work and not for reproducing another artists’ design. There aren’t many artists utilizing engraving today, but Evan Lindquist is one of them. No surprise he has ties to Hayter through his graduate studies at the University of Iowa, where Mauricio Lasansky had founded the printmaking department in the late 1940s (Lasansky worked with Hayter at the New York Atelier 17 in the early 1940s). In recent years, Lindquist has created a series of elegantly engraved portraits of art history’s well-known engravers like Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer, Hendrik Goltzius, William Blake, Hayter, and others. (See his website here: https://evanlindquist.com/seeprints/gallery2.html.) In his engraving, SW Hayter Engraves War, Lindquist portrays Hayter as an intense, powerful figure out of whose burin (his engraving tool) come motifs referring to the Spanish Civil War.

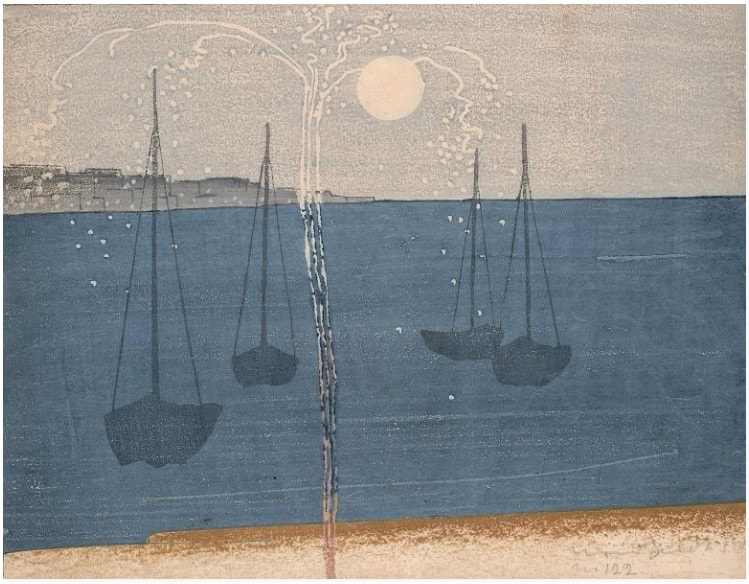

That Lindquist portrays this titan of printmaking creating a print in support of victims of a crazy war, and not as a teacher, is telling. Hayter and a group of artists created two portfolios, Solidarité (1938) and Fraternity (1939), that were fundraisers for the child victims of the Spanish Civil War. Hayter’s plate for Fraternity, which also contains prints by John Buckland Wright, Dalla Husband, Josef Hecht, Wassily Kandinsky, Roderick Mead, Joan Miró, Dolf Reiser, and Luis Vargas, shows a nude male standing in a doorway while an airplane flies overhead. One can’t help but think of Guernica, the small Spanish village that was bombed in April 1937, killing vast numbers of civilian men, women, and children. Occurrences like Guernica motivated many artists to create work in protest, mostly famously Picasso, and Hayter was no different. He was a passionate humanist who used art to express his profound discomfort with the darkness that befell humanity during the first half of the twentieth century. That the symbols and marks of the war are spitting out vigorously from Hayter’s burin in Lindquist’s portrait is a perfect homage. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Untitled, from the portfolio Fraternity, 1936 Engraving Sheet: 211 x 161 mm. (8 5/16 x 6 5/16 in.) Plate: 124 x 73 mm. (4 7/8 x 2 7/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Sidney Hollander, Baltimore, BMA 1996.8.3 Evan Lindquist (American, born 1936) SW Hayter Engraves War, 2015 Engraving Sheet: 388 x 310 mm. (15 1/4 x 12 3/16 in.) Plate: 278 x 207 mm. (10 15/16 x 8 1/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of an Anonymous Donor, BMA 2015.173 Ann ShaferI had the chance occasionally to acquire objects for the BMA’s collection at auction. It was always exciting, particularly when we won. The museum acquired an impression of this print, B.J.O. Nordfeldt’s The Skyrocket in this manner from Swann Auction Galleries in 2012.

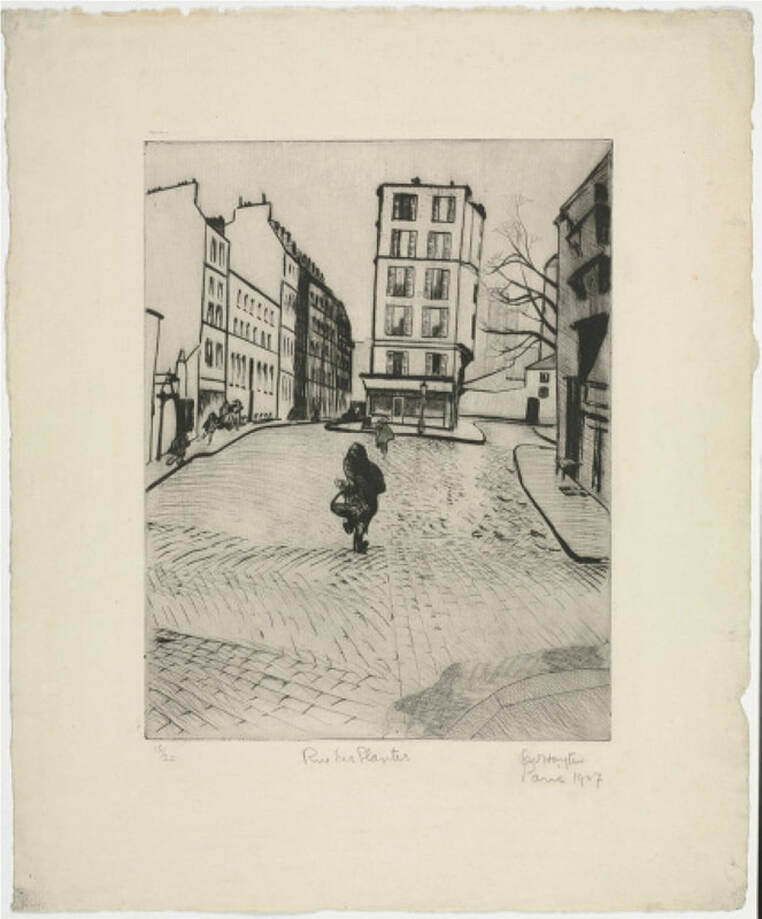

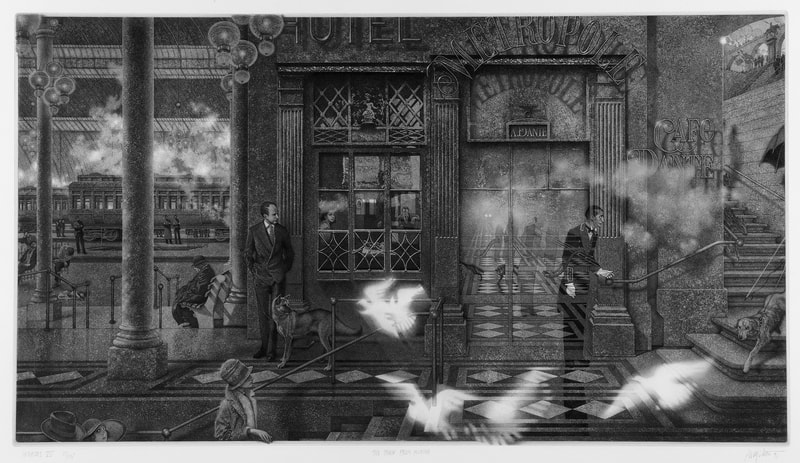

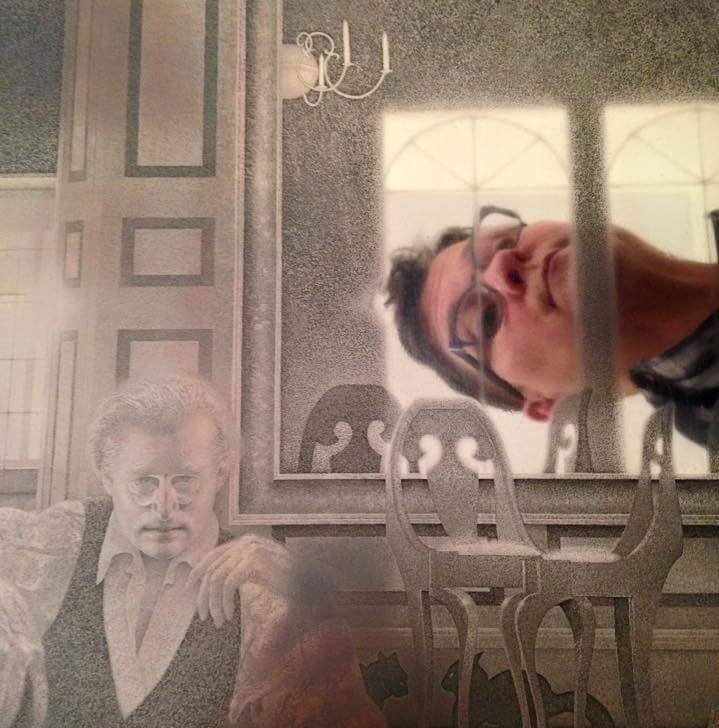

The Skyrocket is my favorite of Nordfeldt’s woodcut compositions, which have a distinctive Japan-esque quality to them. (He also made etchings, which are more reminiscent of Whistler’s Thames series.) Inspired by 19th-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts, Nordfeldt developed a new method of printing color woodblocks. Instead of carving multiple blocks to carry individual colors in the Japanese manner, Nordfeldt carved images onto a single block, and inked each section with a different color. Sometimes, to keep colors separate on the block, small grooves were carved between each segment that create distinctive white lines in printing. This white-line style became a hallmark of his and other artists’ works made in Provincetown in 1916 and onward. That doesn’t appear to be the case here, and it is a decade before those works, but the design sensibility is definitely present. You should know that the image I’m showing here is the impression from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It’s slightly different in its printing, though the colors are similar. For instance, the BMA impression has less of that brown along the bottom. I can’t show the BMA’s impression because it is not included on the online database. Not every object is available on the website and I suspect it will be many years before the online database includes everything. More reasons to make an appointment to see the work in person after the pandemic has eased and museums reopen their doors to the public. B.J.O. Nordfeldt (American, born Sweden, 1878–1955) The Skyrocket, 1906 Color woodcut on Japan paper Image: 220 x 285 mm. (8 ¾ x 11 1/4 inches) Smithsonian American Art Museum: Gift of L. Laszlo Ecker-Racz Ann ShaferI’ve been teaching myself Adobe’s video editing software, Premiere Rush. Today is the debut of my first attempt, a very short video on Stanley William Hayter’s Rue des Plantes, 1926. For our epic research trip to Paris in 2015, Ben Levy, Tru Ludwig, and I had a lot on our to-do list related to the Hayter exhibition. First on the list was to photograph and film the printing of Hayter’s Torso, 1986, at Atelier Contrepoint, which I wrote about in another post. Second was to interview Désirée Hayter on video. Third was to find and photograph as many locations of the Atelier as possible (it moved a bunch of times). And fourth was to find, photograph, and videotape the locations that appear in Hayter’s series Paysages urbains, 1930 (more on that in another post). While doing the last, I added finding the site of Rue des Plantes to the list. Rue des Plantes is a lovely early drypoint by Hayter depicting a simple street scene in the 14th arrondissement. In it a lone figure carrying her daily market purchases walks toward a building that oddly is situated in the middle of a cobblestone street. Finding the site wasn’t too hard, but finally laying our eyes on it sparked our adrenaline. Ben set up the video equipment intent on taking some B-roll for an eventual video for the exhibition website. With the camera rolling, suddenly an older woman carrying her market purchases wandered into the frame. The three of us must have looked like lunatics gesturing to each other madly but silently so as not to be recorded on the tape. It couldn’t have been more perfect. Finally, I’ve pulled a short video together showing this golden moment, which thrills me still. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988) Rue des Plantes, 1926 Drypoint Sheet: 400 x 328 mm. (15 3/4 x 12 15/16 in.) Plate: 267 x 208 mm. (10 1/2 x 8 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Bequest of Ruth Cole Kainen, Chevy Chase, Maryland, BMA 2011.263 Ann ShaferI’m a super fan of intaglio printmaking—intaglio refers to printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink—and I always wanted to do a series of shows on techniques, starting with, of course, intaglio. (Sorry folks, lithography would be last; well, maybe screenprinting.) Stanley William Hayter was a great practitioner of intaglio printmaking, as were all of the artists who worked with him at Atelier 17. Many of them established or ran university printmaking departments, including Gabor Peterdi, who taught at Yale from 1960 to 1986. One of Peterdi’s students was Peter Milton, who must stand as one of the great intaglio printmakers of the latter part of the 20th century.

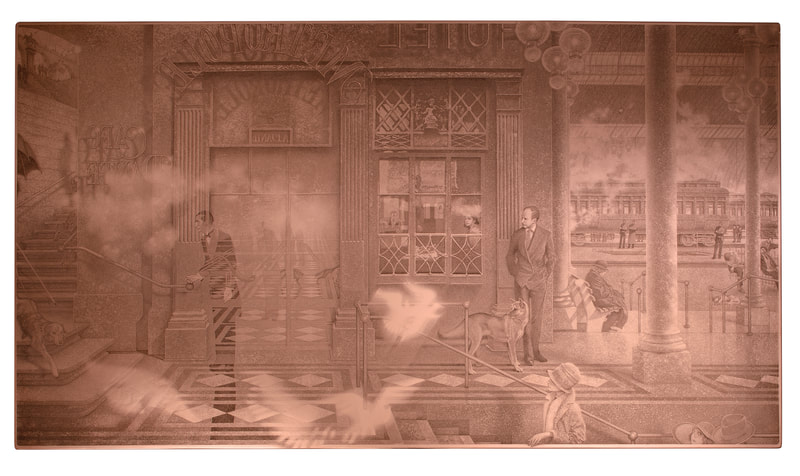

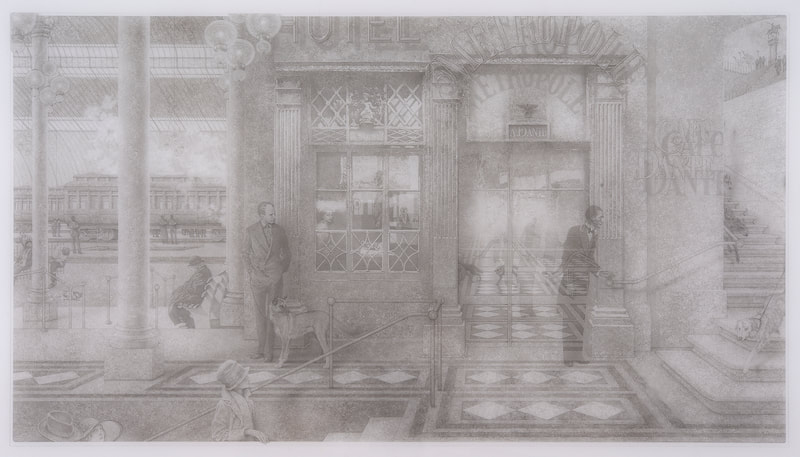

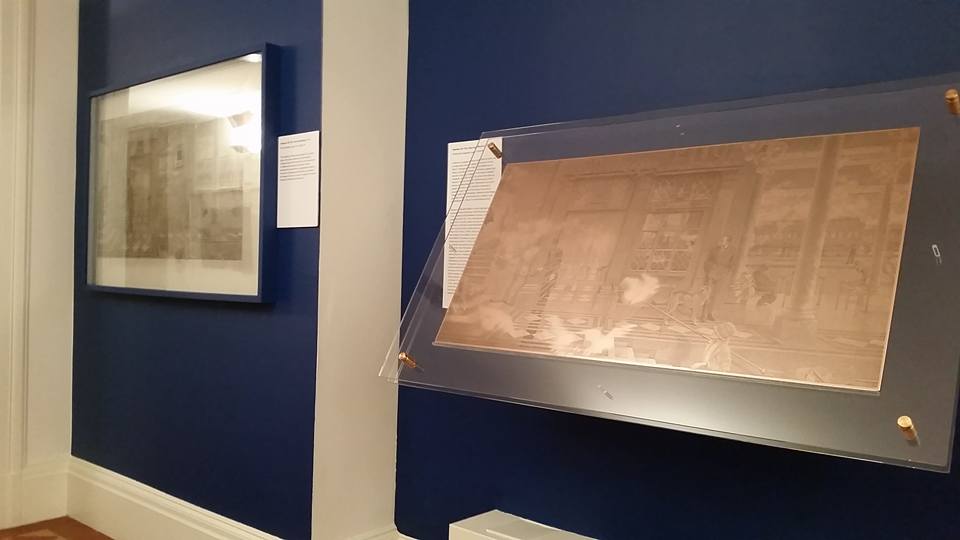

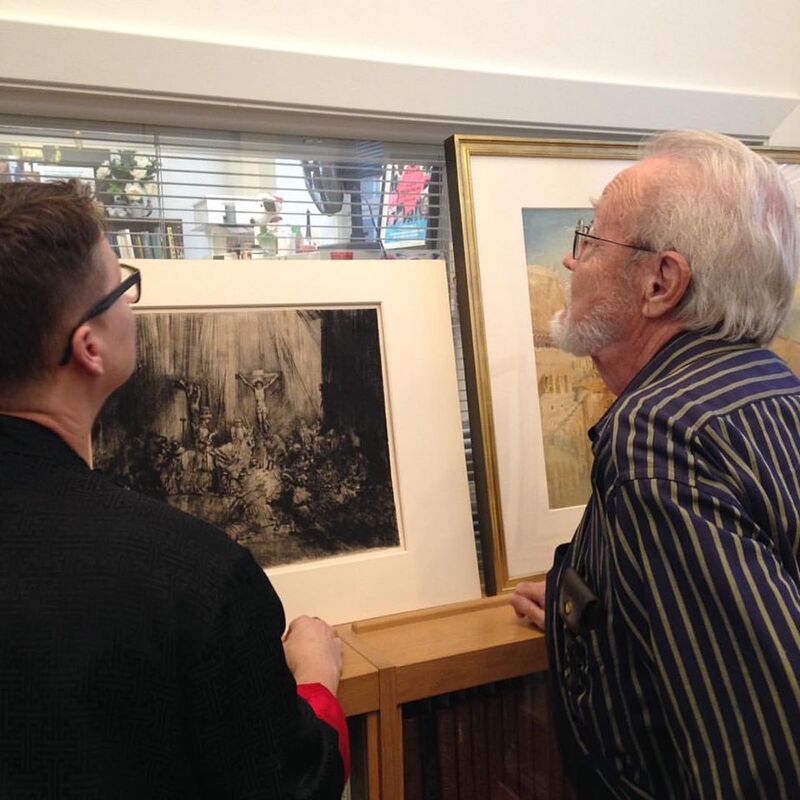

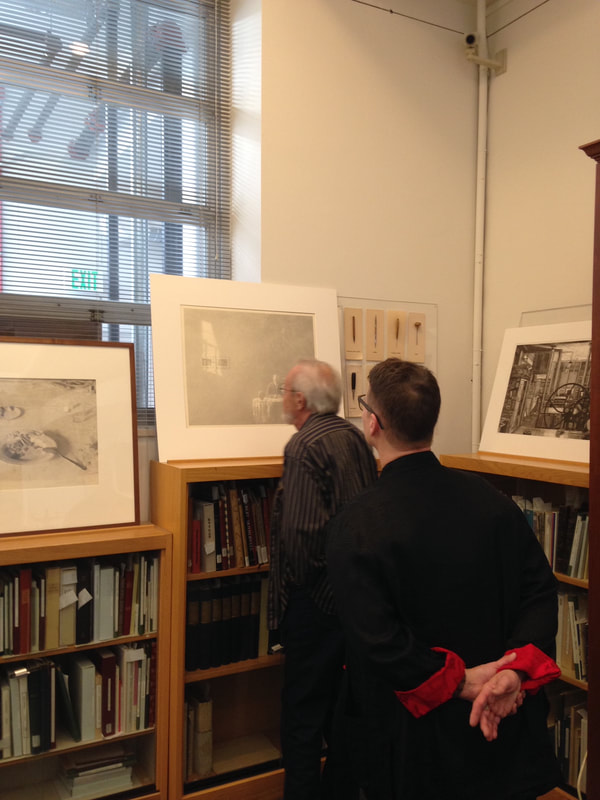

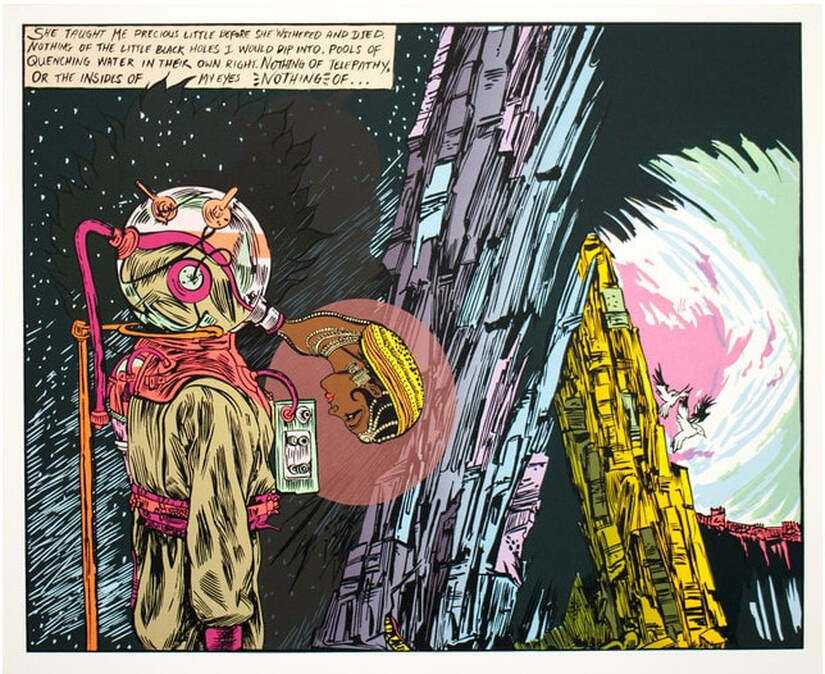

The BMA has a handful of Milton’s prints. One of the most spectacular, Interiors IV: Hotel Paradise Café (1987), is mindblowing for students in MICA professor Tru Ludwig's History of Prints classes. Upon its unveiling one would hear choruses of “wow!” along with mutters of “it’s so not fair.” Its intricacies have both inspired and depressed young printmakers. Tru and I are both fans and when we had the opportunity to hear Milton speak at Jane Haslem’s Washington, D.C., gallery, we jumped at the chance to meet him. After the talk we approached and he and Tru bonded over everything from techniques to history to all the esoteric details that appear in his prints. It was also there that I spied one of his drawings for his series The Aspern Papers, which I eventually acquired for the BMA—more on that in another post. During their conversation, Peter told Tru that he considered the copper plates to be the most beautiful things he makes. The lightbulb went off and the next thing we knew, Tru and I were working together with James Archer Abbott, then director of Evergreen Museum and Library, to curate an exhibition of Milton’s plates, prints, and preparatory drawings. Several trips were made to Milton’s New Hampshire studio and home, where we were welcomed by Peter and his lovely wife, Edith. There we got to interview him, see where the magic happens, and select the plates and other works to be included in the show. To my mind, Milton’s Interiors series is his most important. We included five of the seven plates from that series including The Train from Munich (1995), which focuses on Edith’s 1939 departure from Germany as one of 10,000 children sent on a Kindertransport train taking unaccompanied Jewish children to the United Kingdom for the duration of the war. [Edith and her sister lived with a British family for seven years and she eventually published an excellent memoir about that time called Tiger in the Attic (a NYT review is here: https://bit.ly/MiltonTigerinAttic).] The Train from Munich graces the cover of the catalogue produced for the Evergreen show and it is written about in depth therein. The link to the PDF catalogue is here: https://bit.ly/MiltonCatalogue. Working on the show, I think Tru had the most fun job. He was the muscle responsible for polishing the copper plates. This is no easy task and takes patience and perseverance. In the end, we both agree with Peter. The copper plates are stunningly beautiful and reveal things, objects, and moments that are easily missed in the printed versions. It was an honor to work with this titan of printmaking. And, we owe one last thank you to Jim Abbott for letting us make a dream come true. Ann ShaferWhen the museum acquired Chitra Ganesh’s work, I already had the seed of a show growing in my mind. I had been asked to come up with an exhibition drawn from the collection featuring works by artists of color. This is problematic on many levels. I have always believed that separation is sometimes useful, but that integration must be the goal. In any case, the works available for a show of that sort lacked any thematic cohesion. At the same time, I’d had many MICA students inquire about seeing works from the storeroom that reflected a graffiti or comic book sensibility. The collection did not have much to offer. It took time and several acquisitions to bring together an exhibition that focused on the theme of alternate realities—artists looking at real-world problems through visual fantasies, comics, sci-fi. Ganesh’s gorgeous print fit the bill beautifully and was installed along with prints by Trenton Doyle Hancock, Wangechi Mutu, Toshio Sasaki, Enrique Chagoya, William Villalongo, iona rozeal brown, Raymond Pettibon, and Amy Cutler. On Paper: Alternate Realities was on view September 21, 2014–April 12, 2015. It was the most organically diverse show of my career and remains one about which I feel extremely proud.

I love a print that looks cool and asks more questions than it answers. Chitra Ganesh’s Away from the Watcher is a colorful combination of screenprint and woodcut that features an enigmatic figure at left (in a scuba or space suit—you decide) who seems to be exhaling an Indian goddess figure, while watching a city on a hill possibly being destroyed. Along the top left is a comic-strip-style thought bubble that reads: “She taught me precious little before she withered and died. Nothing of the little black holes I would dip into. Nothing of telepathy, nor the insides of my eyes. Nothing of…” This image raises many questions: Is somebody inside the scuba/space suit—isn’t it propped up? Is the Indian goddess figure being expelled or inhaled? Are we underwater or in outer space? What do the small winged creatures signify? What calamity has befallen the city at right? The somber melancholy of the text seems at odds with the dynamic depiction of the planet’s fissures, as well as the brilliant color and energetic comic-book style of representation. These alternate moods and narratives clash and connect in a newly constructed vision of the future. Chitra Ganesh (American, born 1975) Printed and published by Durham Press Away from the Watcher, 2014 From the series Architects of the Future Woodblock and screenprint 629 × 797 mm. (24 3/4 × 31 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of an Anonymous Donor, BMA 2014.29 Ann ShaferIf ever I turned my attention to making art instead of writing about it, I would pull out my watercolors and brushes and head outdoors. It’s hard to imagine a world when that wasn’t possible—but it wasn’t so long ago that the first paints in tubes became commercially available. The first premixed watercolors were introduced to the market in England in the 1760s, but it wasn’t until the 1840s that those little tubes we know today were invented.

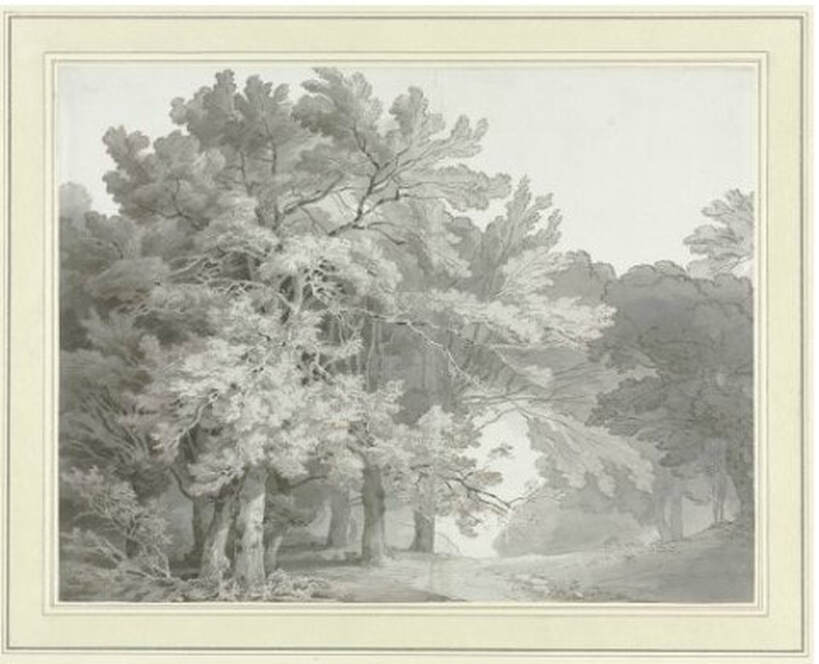

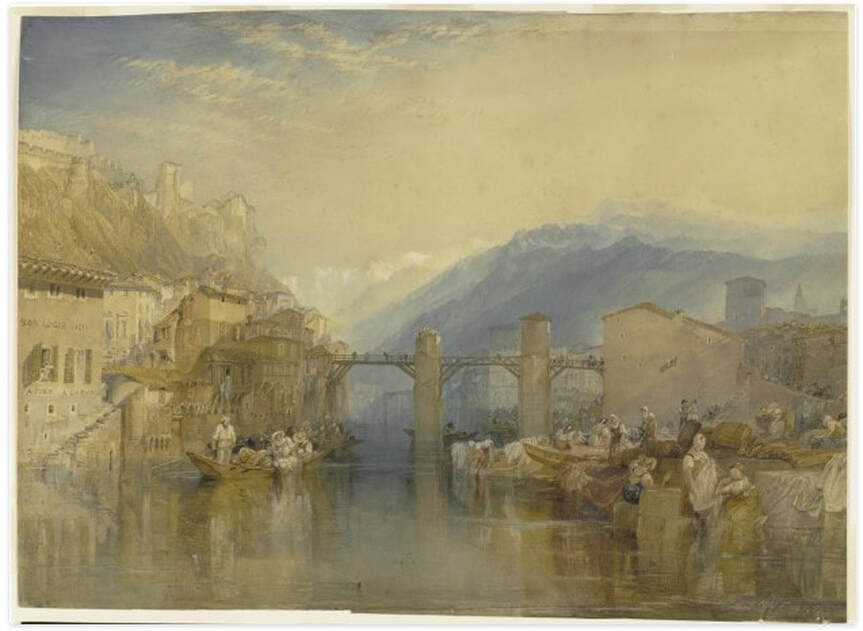

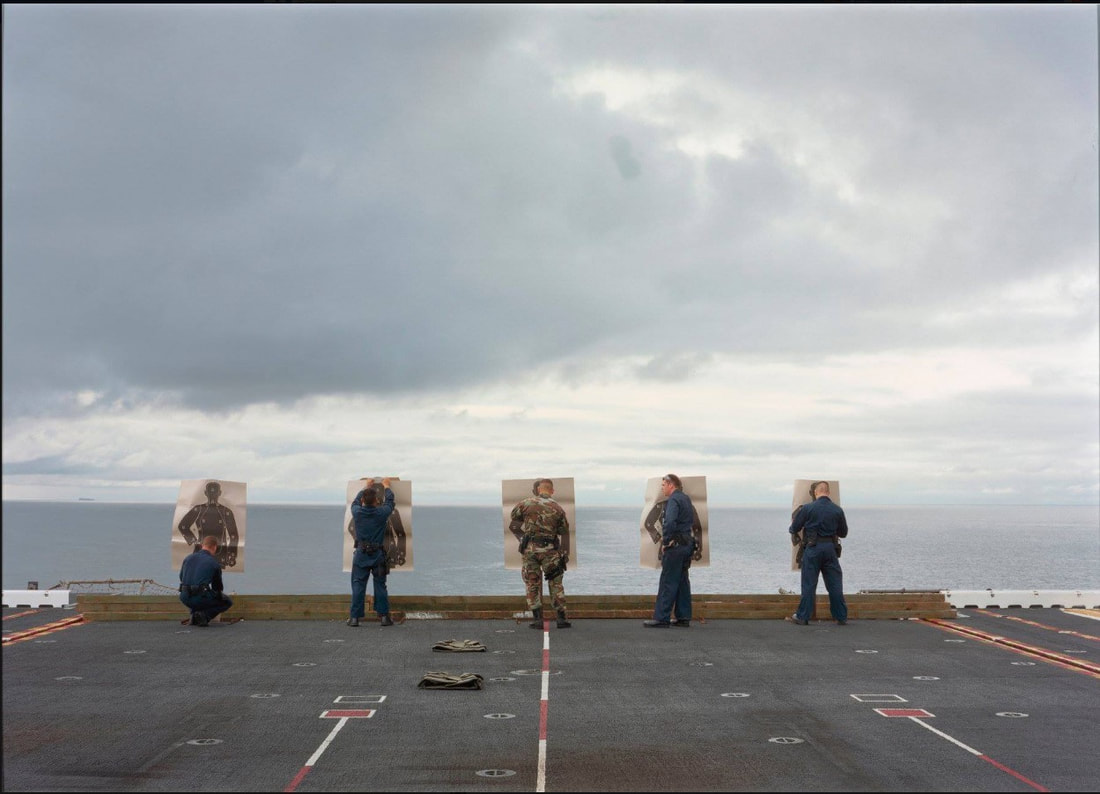

The proliferation of watercolor landscapes in England in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was due in no small part to the introduction of those premixed watercolor paints. Artists began to experiment with the medium and test the boundaries of what could be accomplished. Soon these works found their way into the annual exhibitions of the English Royal Academy, but they were so marginalized that a group of artists split from the Academy in 1804 to establish the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. The goal of this new Society was to place watercolors on an equal footing with oil paintings, and artists responded by creating large-scale, highly finished watercolors displayed in elaborate gold frames. The Baltimore Museum of Art is fortunate to have an example of one of these presentation watercolors by Britain’s favorite son, Joseph Mallord William Turner. In contrast to the highly finished exhibition watercolors, many artists created more intimate works in the same medium. Artists went outdoors with sketchbooks and paints to test their skills at portraying the landscape. One such work from a sketchbook (notice the crease down the center) is a favorite acquisition. The artist is John White Abbott, a country surgeon and apothecary from Exeter, who as an amateur artist painted for his own enjoyment (the term amateur indicates only that the artist did not earn money making art, but is no indication of a lack of talent). After inheriting an estate from his uncle, he was able to devote himself full time to painting. Abbott probably drew A Path through the Woods first in graphite pencil on the spot, and then returned to his studio to finish the work with gray washes and pen and brown ink. I continue to be amazed at the quality of light through the dappled foliage painted with just gray and brown. In fact, the execution is so masterful that I see this monochromatic scene in full color. In addition, the peacefulness of the scene always transports me to somewhere else. For me, this work is a figurative and literal breath of fresh air. John White Abbott (English, 1763‑1851) A Path through the Woods, c. 1785‑1795. Pen and brown and gray ink with brush and gray ink over graphite Sheet: 256 x 335 mm. (10 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Rhoda Oakley, Baltimore, BMA 2008.9 Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, 1775‑1851) Grenoble Bridge, c. 1824. Transparent and opaque watercolor with scraping over traces of graphite Sheet: 530 x 718 mm. (20 7/8 x 28 1/4 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased with exchange funds from Nelson and Juanita Greif Gutman Collection, BMA 1968.28 Ann ShaferFile this one under it's not always about prints and printmaking. In the fall/winter of 2013-14, the BMA showed the work of photographer An-My Lê (pronounced Ann-Mee Lay). It was an honor to work with her and, as often happens, the museum acquired one of the photographs from the show. When it came time to select objects to talk about on video for the BMA Voices initiative, this one was a no-brainer. It's got it all. Here's the link to the short video we made: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fuT0JHVXmE. In the brochure for the exhibition, I concluded in this manner: In their quiet, unassuming way, Lê's sublime landscapes remind us that war is complex and contradictory. Alongside the brutality of combat, there is also the thrill of danger and adventure. Where there is enormous loss, there is also honor. Where there is heated protest, there is also heartfelt patriotism. By calling attention to the global reach of the U.S. military, Lê's photographs point out how martial power is balanced by humanitarian assistance and support of scientific research. Any discussion of the military will be polarizing, but Lê is able to find equilibrium between opposing points of view. While her photographs appeal to conservatives who see her work as pro-military, they also speak to liberals who read her work as anti-war. In drawing back the curtain to reveal the inner workings of the military as a giant facet of the global economy, Lê's photographs encourage us to think about its many complexities. An-My Lê (American, born Vietnam, 1960) Target Practice, USS Peleliu, 2005 Inkjet print, pigment-based Sheet: 1016 x 1435 mm. (40 x 56 1/2 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2014.5 Ann ShaferFile this post under nothing lasts forever, even on the interwebs. For the BMA's 100th birthday, staff produced 100 blog entries on favorite collection objects. Some were videotaped pieces featuring curators, conservators, and other staff speaking on camera; other entries were written posts. I went to look for my written pieces on artbma.org and couldn't find them anywhere (thankfully, the videos are still on YouTube). Thanks to Laura Albans, I have recovered the text for my entry on Dürer's Knight Death and the Devil, portions of which I share here.

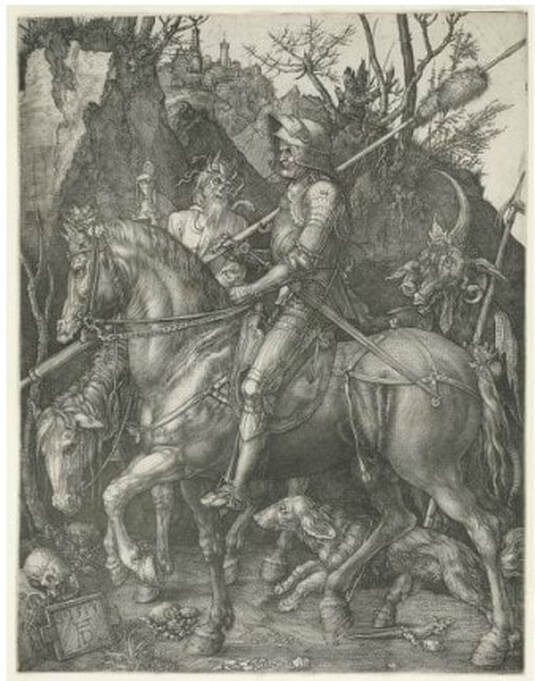

The best part of working in a large collection of prints, drawings, and photographs is the range of material. I used to always say that you could come up with almost any theme and find an entire exhibition on it drawn out of the solander boxes. Since my interests tend toward the 20th and 21st centuries, it may surprise some of you, then, that Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil is one of my favorite prints of all time. Not only is it a glorious example of engraving, but also it carries a universal message to stand by the courage of your convictions. Albrecht Dürer was a German printmaker, draftsman, painter, observer of nature, and humanist. In 1513 and 1514 he created a trio of engravings that have come to be called his master prints. In addition to Knight, Death and the Devil, the trio includes St. Jerome in His Study and Melencolia I. Most scholars agree that the former represents the active life, while the two others represent the intellectual life and the contemplative life respectively. While the three prints together are spectacular, I’m most drawn to Knight, Death and the Devil. The image is a visual feast. It features a righteous German knight resplendent in armor, a horse straight out of Renaissance Italy, a wonderful and faithful companion Fido the dog, and gnarly creatures representing Death and the Devil, all set in a naturalistic landscape. Contemporaries of Dürer would have understood the symbolism of every aspect of this print. But our own unfamiliarity with those symbols doesn’t lessen the impact of the work. Clearly this stalwart fellow is making his way through the forest of temptation and vanitas. He is able to keep to his path, ignoring all that is going on around him and stands by the courage of his convictions. Even if we strip the image of its religious associations of pre-reformation Catholicism, the message of perseverance is clear. Stick to your guns, well, lance, and you can get through anything with grace and dignity. A message as important today as ever. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528) Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513 Engraving Sheet (trimmed within platemark): 244 x 187 mm. (9 5/8 x 7 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Alfred R. and Henry G. Riggs, in Memory of General Lawrason Riggs, BMA 1943.32.188 This image is less than stellar, serving as an excellent reminder that it's always better to see works like this in person. Ann ShaferSometimes you get lucky and come across an artist by chance whose work you love. Even better is when you become friends. I made a studio visit to an artist who happened to be married to Susan Harbage Page. Because their studios were adjacent, I was able to see both in one visit. Susan's work runs the gamut: photography, drawing, performance, fibers, writing. One project has always risen to the top for me. The Border Project is a long running exploration of immigration issues focused on the border at the Rio Grande river in Brownsville, Texas. (An exhibition catalogue about the project is available here: https://susanharbagepagedotcom.files.wordpress.com/…/1_bord….)

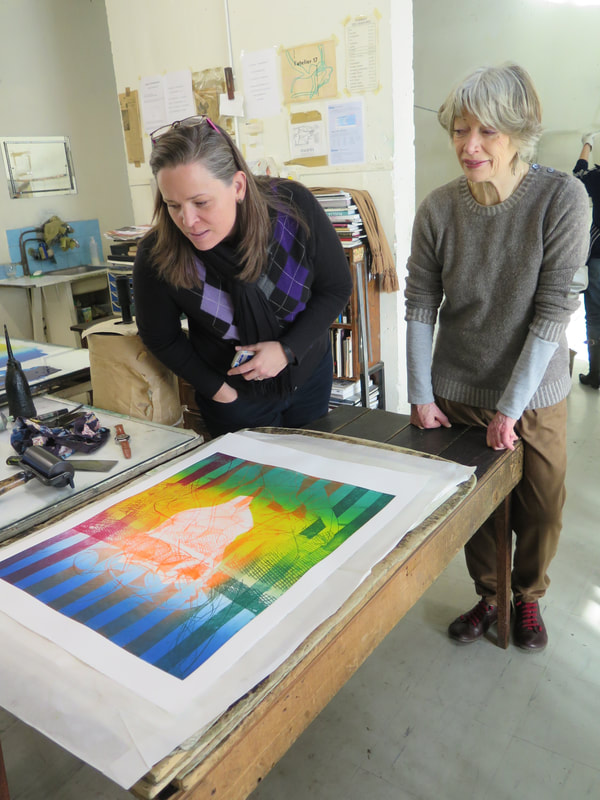

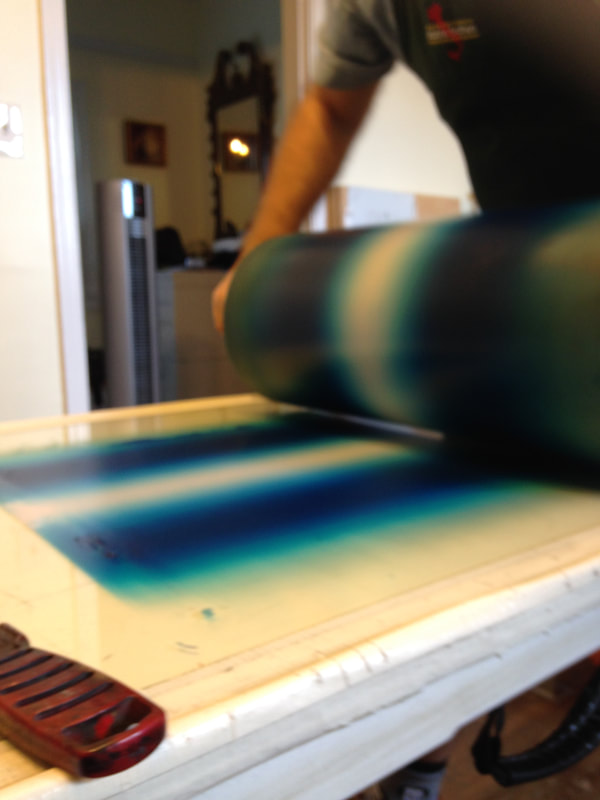

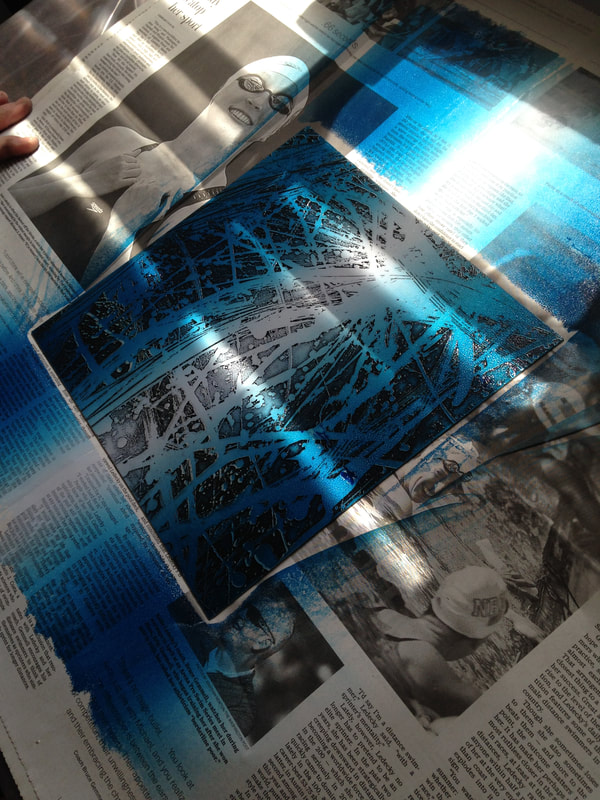

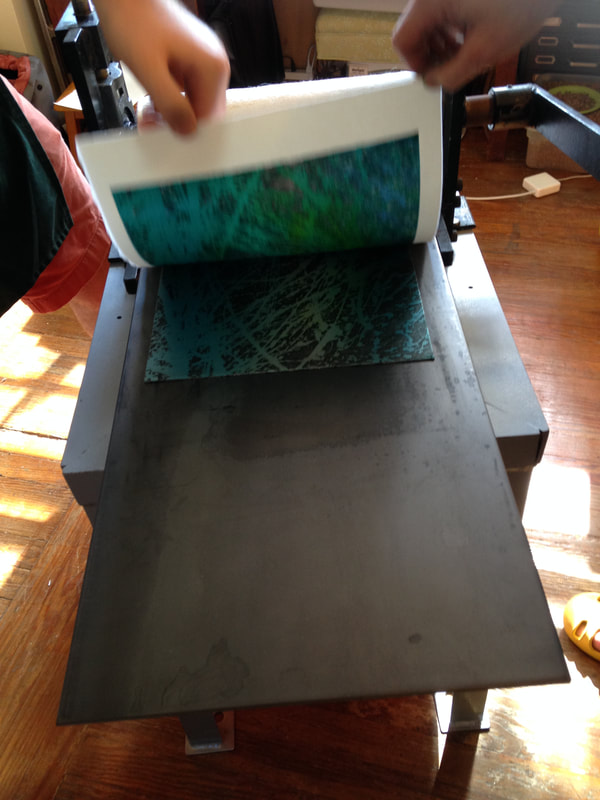

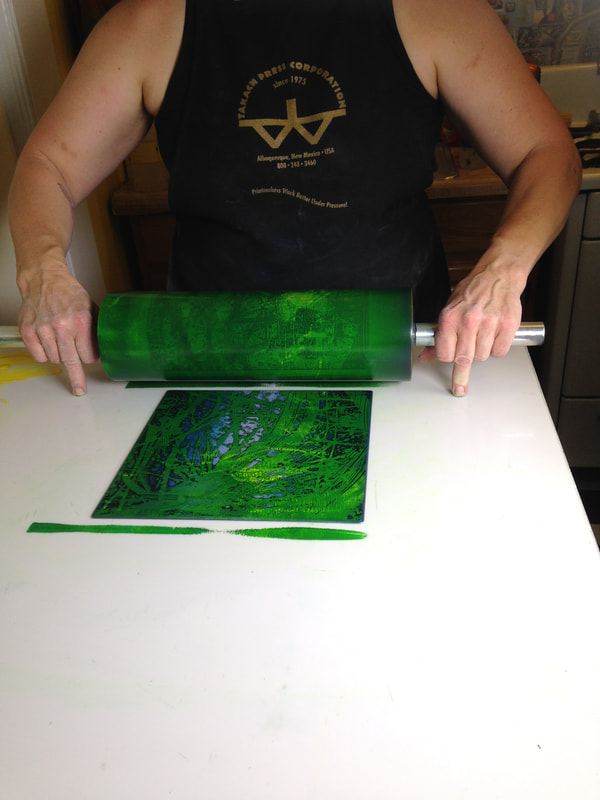

Long before children were being separated from their parents, Susan spent a lot of time photographing objects in situ and then collecting them. The objects left behind by migrants--bras, wallets, identification cards, shirts, toothbrushes--are catalogued and photographed in an anti-archive. The large-scale, color photographs of objects in the landscape hold power for me. Yet, sometimes no object is needed as evidence of a human presence. In Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, a human-sized divot in the dry, tall grasses has been recently used as a resting or hiding place after crossing the border from Mexico. Easy to miss, once we understand how these crossings occur, we will recognize signs like this one forever. This now-empty nest is simple, stark, potent, and full of untold stories both of hope for a better life and fear of capture. Susan Harbage Page (American, born 1959) Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, 2011, printed 2012 Inkjet print, pigment–based Sheet: 1067 × 1553 mm. (42 × 61 1/8 in.) Image: 965 × 1448 mm. (38 × 57 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of the Artist, BMA 2012.156 Ann ShaferYou might be surprised to learn that Hayter's workshop is still operating in Paris at 10, rue Didot. After his death in 1988, the workshop changed its name to Atelier Contrepoint and is run by Hector Saunier, who printed many of Hayter’s late compositions. I was fortunate to be able to visit the Atelier twice, in 2014 and 2015. The first time was to meet Hector and see what the operation looked like. The second time Hayter's widow, Désirée, agreed to bring over one of his plates so Hector could ink and print it for us (there is no one better suited for this particular task). The plan was to create an online feature for the exhibition’s web site, which never happened because the show was cancelled. As usual, Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig were with me, and between the three of us, we shot a lot of video and photographed Hector and Shu-lin Chen printing Hayter’s Torso, 1986.

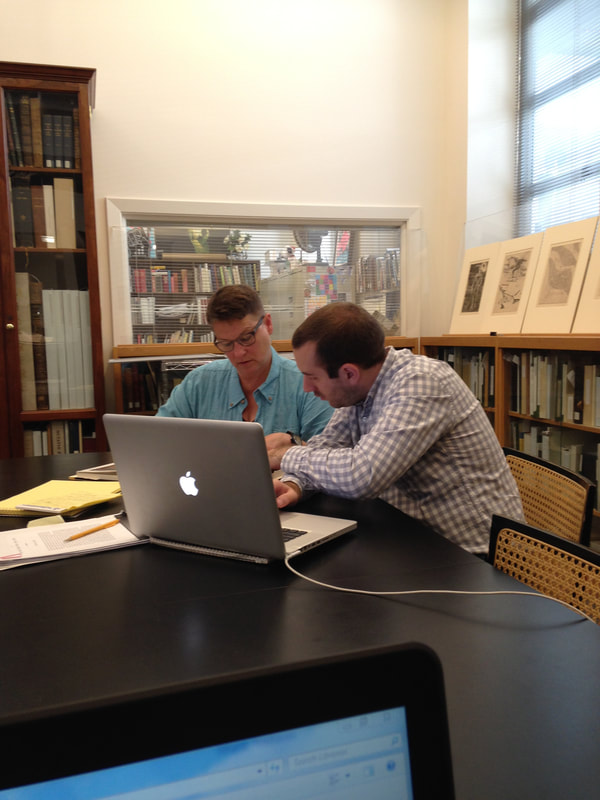

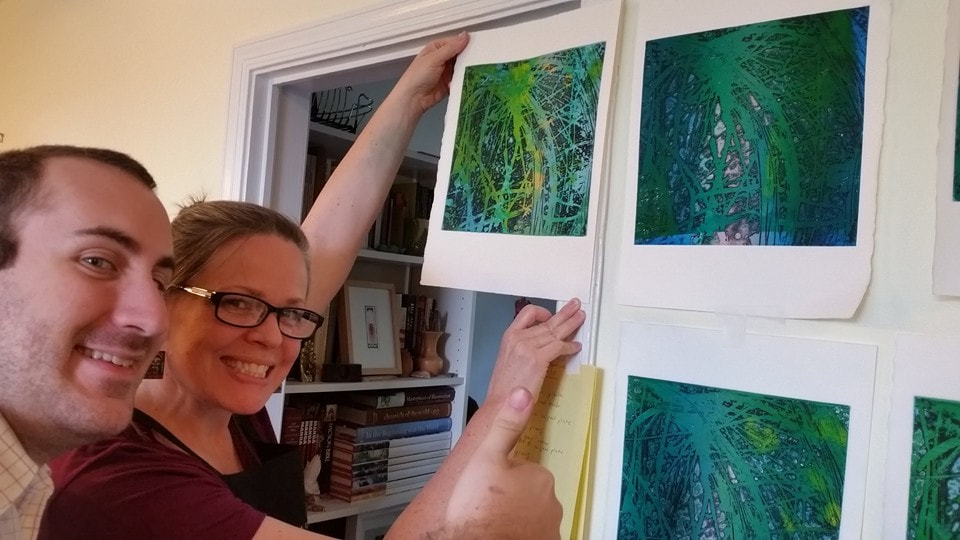

Désirée couldn’t find the plate she was originally thinking of, so she randomly selected Torso, which turned out to be serendipitous because Torso conceptually circles back around to the fist clenching the void discussed in an earlier post. In Torso, Hayter used stripes with inverted color variants, inking the central intaglio composition in green, red, and fluorescent orange, and with a horizontally rolled gradient of blue/yellow/green. The shape of the torso is defined by a mask that was laid down on the inked plate, blocking the rollers from depositing the blue, yellow, and green ink on the paper, producing an area of white across the center. The positive shape of the torso, described by an absence, echoes the conundrum of the untitled plate six from The Apocalypse, in which the negative space of a clenched fist is described by a positive volume. In this late print, the cognitive inquiries and accumulated techniques of four decades have come together. With the copper plate under her arm, we met Désirée on the appointed day at Atelier Contrepoint. After consulting the catalogue raisonné, they got right to work. Shu-lin set about inking the plate (intaglio) in red, fluorescent orange, and dark green in vertical stripes. Hector prepared the rainbow roll of blue, yellow, and green on a glass palette. The mask was still wrapped with the plate, so it was used as well. When Shu-lin was satisfied with her wiping job, the plate was ready for the mask’s placement and the rainbow roll. Hector completed his part and the plate was placed on the bed of the press that had been used for thousands of prints by hundreds of artists over the majority of the twentieth century. After a few unsatisfactory pulls, they printed four impressions, one of which eventually entered the Baltimore Museum of Art’s collection. I remain amazed that I got to experience the printing of one of Hayter’s plates and so appreciative of Désirée, Hector, and Shu-lin’s generosity that day. Even better, Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig were with me to witness the magic. Ann ShaferIn my previous post I talked about Stanley William Hayter's 1959 open bite etching Cascade and promised to dig into its making. It takes many images to describe the process of simultaneous color printing, so I created a PDF slide deck to illustrate how Ben Levy, Tru Ludwig, and I made a group of test prints to figure it all out. You can find the PDF here:

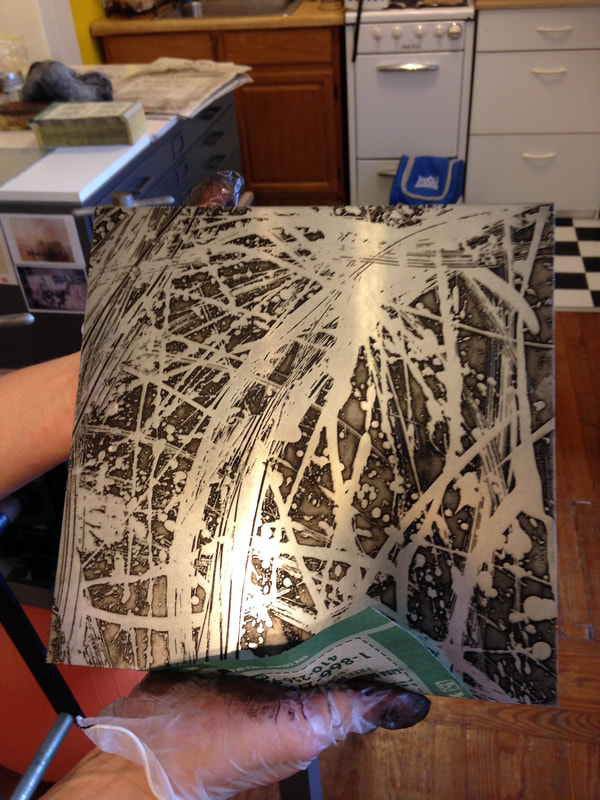

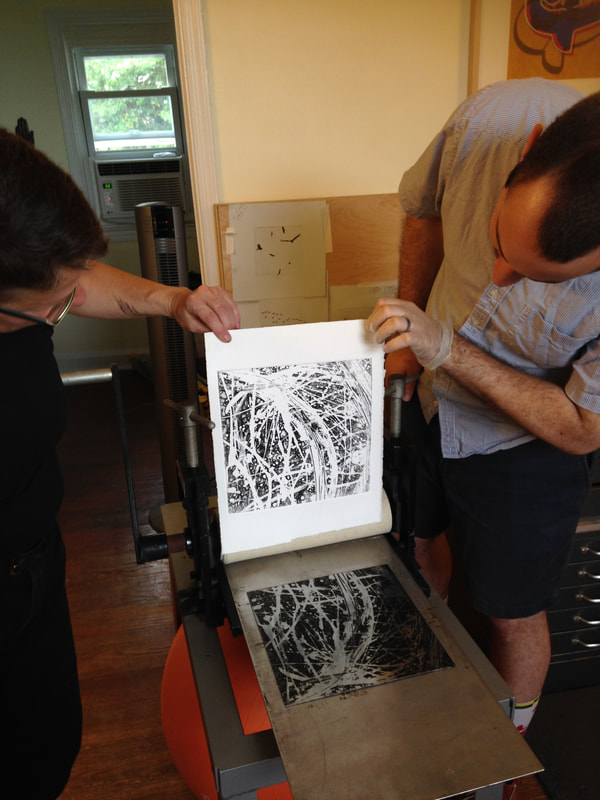

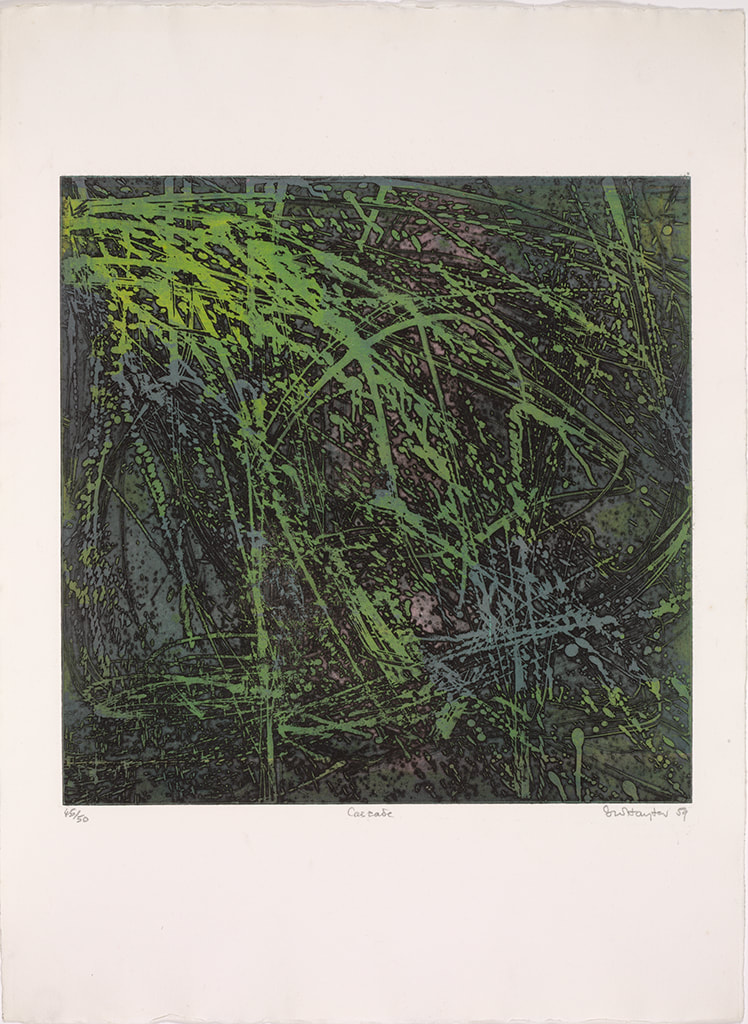

Ann ShaferCascade, 1959, by Stanley William Hayter, is the print I planned to use of the cover of the catalogue. One, because it's gorgeous. Two, because by 1959, Hayter is 58 and had been at it for more than thirty years and Cascade sums up so much of Hayter's thinking. During that time, he's helped Spanish refugees during the Spanish Civil War by hiding them in the studio; he's dropped everything and fled Paris as it went to war with Germany in 1939; he's created something really special in NY during the war and following (he's in NY from 1940-1950); he's watching his 16-year-old son die in 1946; he's helped hundreds of artists find their voices and discover new ways of creating intaglio prints; he, like so many other artists, has grappled with the horrors revealed by the Holocaust and bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and he's been able to return to France and purchase a vacation home in the south of France. But Hayter was also a man who never stopped thinking, working, creating, loving, living. Three, it's a great place to start talking about one of the Atelier's most important discoveries, that of simultaneous color printing (sometimes called viscosity printing, although Hayter didn't like that term since all inks have a viscosity of some sort).

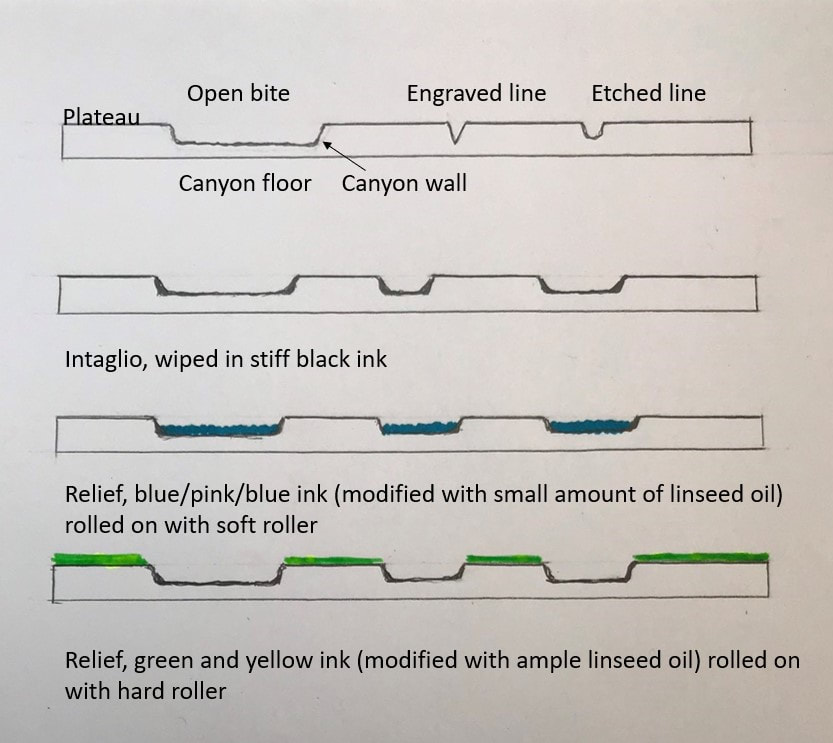

Cascade, 1959, is a colorful print with an all-over composition that appears completely abstract; seemingly random drips and gestures cover the plate. Hayter, however, never accepted pure abstraction as a meaningful subject—even when his subjects defy conventional representation, his titles anchor them in the world of places and things. Cascade is one of many works inspired by the appearance of rushing water in a river near his home in the south of France. The direct autographic drawing that had been essential to Hayter’s work since he began engraving has disappeared, replaced by a variety of devices that could be set in motion by his hand, but whose outcomes were far more open to chance: leaking cans of liquid ground suspended as pendulums, and marker pens that could dribble and spray showers of thin resist. These systems recorded, rather than depicted, the behavior of liquids in motion. Cascade is an indexical print (see prior post about Trisha Brown). Despite all of the scholarly reasons we can cite for Hayter's switch from engraving lines to depict images to indexical splashes of liquid, I've always wondered if his hands were just tired and he was dealing with an onset of arthritis. I have absolutely no proof of this--it's just a thought. What's so intriguing to me about the print is figuring out how in the world a bunch of open-bit swooshes and gestures are inked to produce the colorful image. First, we need to understand that to produce a color print, normally one would create separate copper plates for each color and they would be printed in successive layers on the paper in multiple passes through the press. Instead, Hayter layered the different colors on the same, single plate, and ran it through the press once. The trick is to vary the amount of oil in each color so that they don't run together as they are applied. (This idea was developed at the Atelier by Krishna Reddy and Kaiko Moti--an example of the collaborative nature of the workshop.) Along with the print itself, I'm including an image of the zinc plate (also in Baltimore's collection, a gift from Mrs. Hayter, BMA 2014.40), and an image that shows the cross section of the plate in the order it is inked. I hope this will make some sense; we'll dig in more tomorrow. First, the plate is wiped intaglio in black so that the ink clings to the canyon walls; second, a soft roller carrying the rainbow roll of blue/pink/blue deposits color in the canyons; third, a hard roller deposits an unblended green and yellow across the plateau. This will all be made clearer tomorrow when I share the test plates we created for the exhibition to show each step in this inking process. Because these test plates are the first and only etchings I've ever made, you can imagine I had help. I am deeply, supremely indebted to Tru Ludwig and Ben Levy, who made it all happen. Tomorrow you'll see us in action. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Cascade, 1959 Open bite etching; printed in black (intaglio), blue-pink-blue gradient (relief), yellow, green, and blue, unblended (relief) Sheet: 794 x 584 mm. (31 1/4 x 23 in.) Plate: 489 x 489 mm. (19 1/4 x 19 1/4 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, BMA 2008.112 Ann ShaferIn the previous post I shared a video about Stanley William Hayter (known as Bill to his friends), an artist that has interested me for many years. I also shared a link to a PDF catalogue for an exhibition that took place last year in São Paolo, Brazil. I was lucky enough to participate in a conference there in conjunction with that exhibition, Atelier 17 and Modern Printmaking in the Americas. I’m sharing a summary of the conference I wrote for another publication that I hope you find interesting. And, if you or any of your students need a dissertation topic, read through to the end. The conference was held at the Museu de Arte Contemporãnea, which is part of the University of São Paolo and is known as MAC USP. Both the exhibition and conference focused on printmaking and artistic exchange between the United States and South American countries in the mid-twentieth century. The exhibition, catalogue, and conference were born out of the research of USP graduate student Carolina Rossetti de Toledo, who, under the supervision of professor and chief curator Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, focused on several gifts to São Paolo’s new Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in the 1950s of prints from Nelson Rockefeller, Henry Ford, and Lessing Rosenwald (the majority of MAM’s permanent collection was transferred to MAC USP upon its founding in 1963). Nelson Rockefeller made two gifts, one in 1946 of paintings and sculpture and another in 1951 of twenty-five modern prints, to assist in the establishment of a museum of modern art in São Paolo. (He also donated a group of paintings to a museum in Rio de Janeiro in 1952.) Rockefeller’s interest in Brazil began when he travelled there as the director of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, the purpose of which was to strengthen relations with Latin America during World War II, both politically and culturally. The initial selection of prints for the Rockefeller donation was made by MoMA curator William Lieberman, who chose prints that represented cutting-edge modernism. The majority reflect American printmaking of the time, meaning works by artists associated with Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. Why Rockefeller focused on MAM in São Paolo specifically remains unclear. Whatever the real reason, it was noted as a “gesture of goodwill.” A selection of prints from the 1951 gift were exhibited that year in São Paolo but have rarely been shown in the intervening years. Following Rockefeller’s gesture, Henry Ford donated one print in 1953, and Lessing Rosenwald made a gift of nine modern prints in 1956, which were meant to augment the collection in the area of international modernism. The connection between the three donors and what motivated the Ford and Rosenwald gifts is unclear. But among the prints in these later gifts were yet more examples of international modernism in the form of works by artists associated with Atelier 17. For Brazilian artists, there were three possible points of contact with Atelier 17. The first was through trips abroad. The second was through the publication and circulation of books by Hayter and his associates. The third was through exhibitions such as MoMA’s 1944 Atelier 17 exhibition, which traveled not only around the United States but also throughout Latin America, and through the exhibitions of works by Atelier 17 artists in the São Paolo Biennials and other venues. Hayter had an exhibition in Rio de Janeiro in 1957, which also traveled to Buenos Aires, and his work was included in the British pavilion in the 1959 São Paolo Biennial (MAM purchased several prints from this show). Interestingly, Atelier 17 artist Minna Citron had an extensive one-person show at MAM in São Paolo in 1952, which was by far the biggest exposure of an Atelier 17 artist in Brazil up to that point. Citron was fairly proficient in Portuguese (and many other languages), which may account for how she secured and coordinated this show. Several of the prints in the Rockefeller gift to MAM had been shown in other impressions in the 1944 MoMA exhibition and yet other prints in the gift were seen in Una Johnson’s seminal National Print Annual exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum. In other words, the gift was of cutting-edge contemporary prints. There are still gaps in the story, however. In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, Rossetti de Toledo notes, rightly, that the connections between modern American and European printmaking and its Latin American counterparts are not well understood or properly documented. The Rockefeller gift is one piece of the puzzle. Rossetti de Toledo’s research into the Rockefeller gift developed into the MAC USP exhibition and bilingual catalogue, both majorly supported by the Terra Foundation. In addition to prints from MAC USP’s collection, the exhibition featured loans from the Terra Foundation’s extensive collection of American prints and works from the Brooklyn Museum and Art Institute of Chicago. The conference began with introductory remarks from Magalhães and Terra Foundation curator Peter John (PJ) Brownlee. Rossetti de Toledo spoke about her research on the Rockefeller gift. I introduced Hayter and the Atelier 17, setting the stage for the discussion. Other speakers included Luiz Claudio Mubarac, who gave an overview of Brazilian printmaking in the twentieth century; Silvia Dolinko, who gave an overview of printmaking in her home country of Argentina; Heloisa Espada, who focused on Brazilian artist Geraldo de Barros (he worked at Atelier 17 in Paris in 1951); and Priscila Sacchettin, who spoke about Livio Abramo (he worked at Atelier 17 in 1951–52 and his work appears in Hayter’s book, About Prints). Christina Weyl closed out the conference with her talk on women at Atelier 17, which was an excellent preview of her important, recently published book. Over the course of two days, it became clear that South American printmaking runs in sometimes intersecting but separate tracks from European and American art. While artists cross pollinated through travel, books, and exhibitions, for those of us who study prints, there’s a whole other world of printmakers to be discovered in South America. It is also clear that research on these printmakers is wide open. Brazil lacks the central repository of artists’ papers and archives like our Archives of American Art. Many of the artists’ families remain in possession of the works and papers of their creative relatives. These artists’ estates have not been formalized or catalogued, nor are they easily accessible. Hardly any estates’ papers have found their way into libraries or universities, meaning there is a lot of room for intrepid scholars to uncover the careers of any number of artists. How’s your Portuguese? Need a dissertation topic? As I noted yesterday, the exhibition catalogue was printed in a small run but a pdf of the book is available here: bit.ly/Atelier17MACUSP. I also include a list of Brazilian and Argentine artists who were mentioned repeatedly. Brazilian artist-printmakers of note: Edith Behring (1916–1996) Maria Bonomi (born 1935, she was married to Abramo) Ibêre Carmargo (1941–1994) Oswaldo Goeldi (1895–1961) Marcelo Grassmann (1925–2013) Evandro Carlos Jardim (born 1935) Renina Katz (born 1925) Anna Letycia (born 1929) Maria Martins (1894–1993) Fayga Ostrower (1920–2001) Carlos Oswald (1882–1971) Mário Pedrosa (1900–1981) Gilvan Samico (1928–2013) Lasar Segall (1891–1957) Regina Silveira (born 1939) Argentine artists-printmakers: Hilda Ainscough (born 1900) Mauricio Lasansky (1914–2012) Julio LeParc (born 1928) Fernando López Anaya (1903–1987) Ana Maria Moncalvo (1921–2009) At the exhibition reception: (L-R) Taylor Poulin, Elizabeth Glassman, Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, Peter (PJ) Brownlee, Christina Weyl, Amy Zinck, and Ann Shafer. Photo by MAC USP staff.

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed