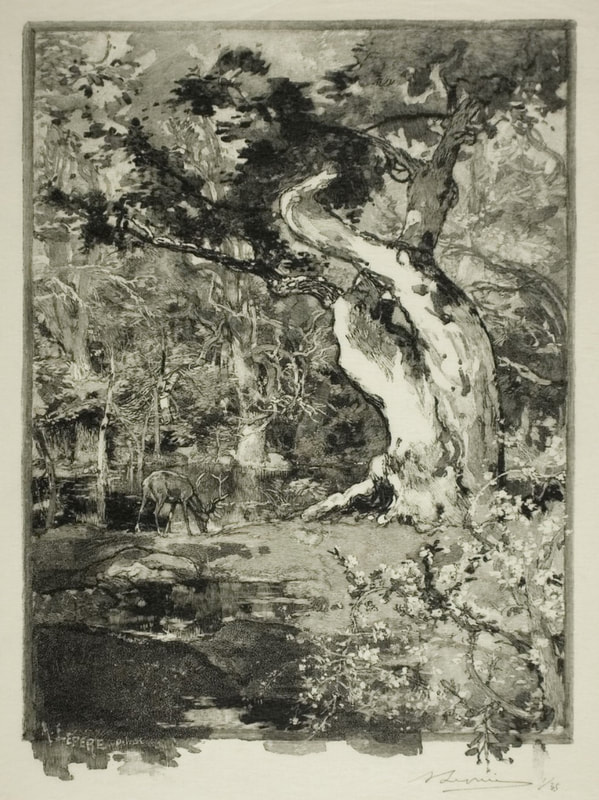

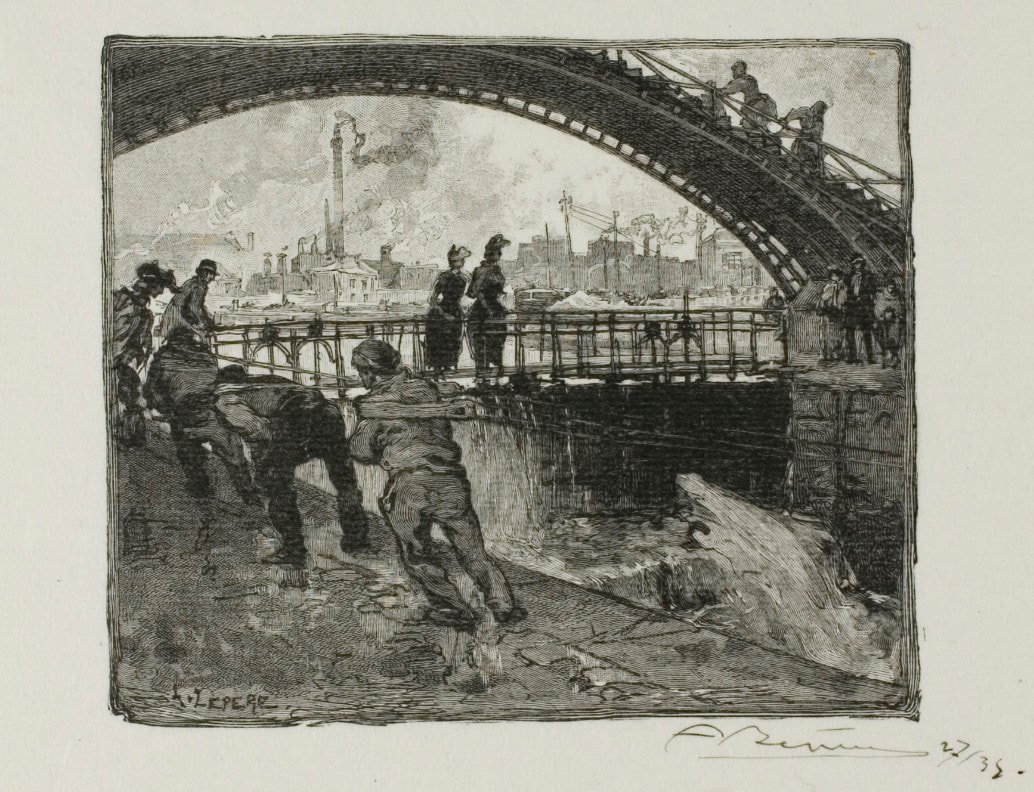

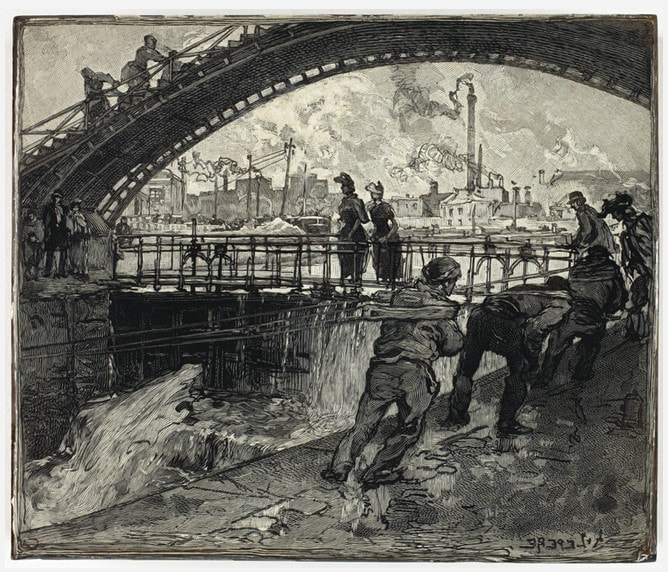

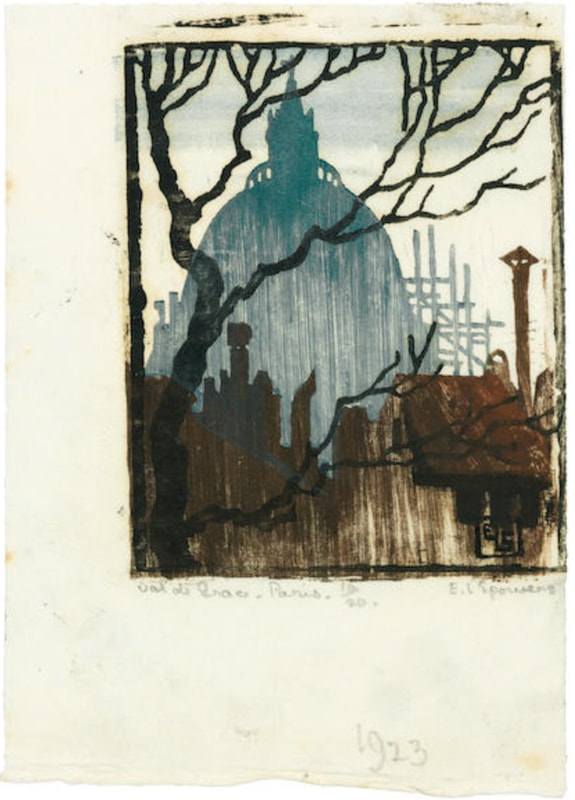

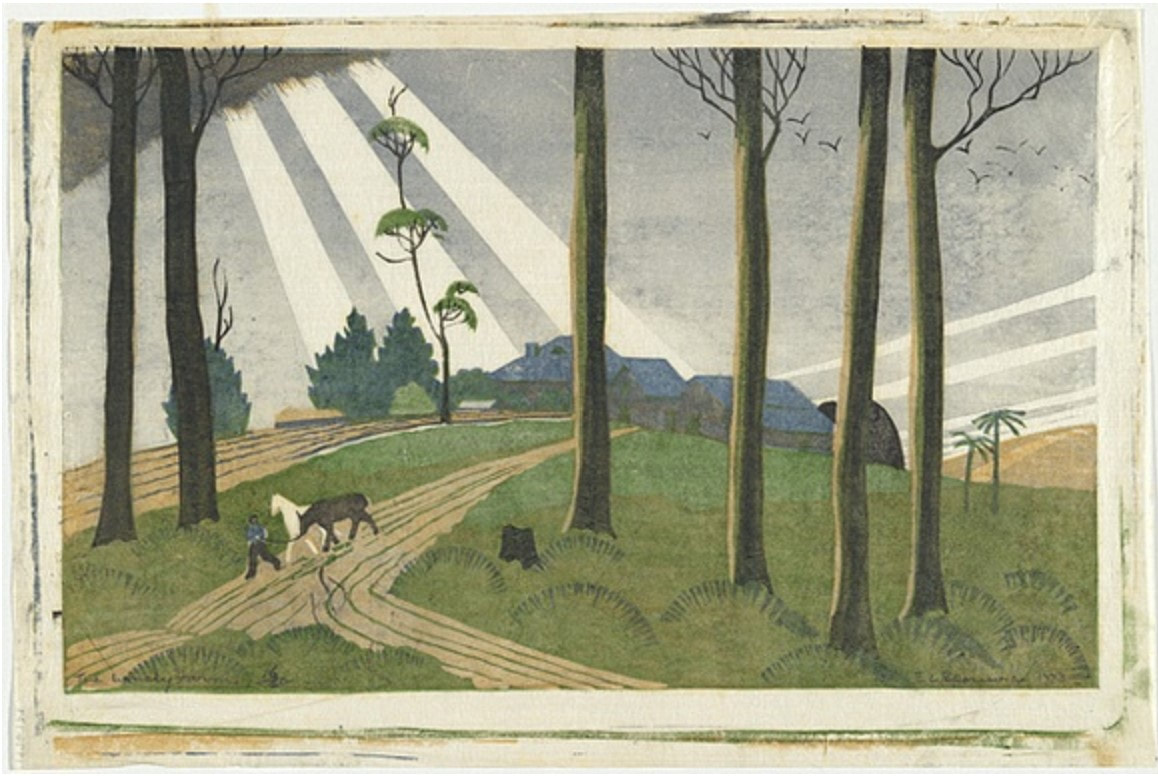

Ann Shafer We’ve looked at many fin-de-siècle artists who made their livings making commercial work for magazines and journals and some who made a living selling fine art prints. But how many artists have we looked at who considered themselves painters who begrudgingly made prints to support themselves? Auguste Lepère was all three.

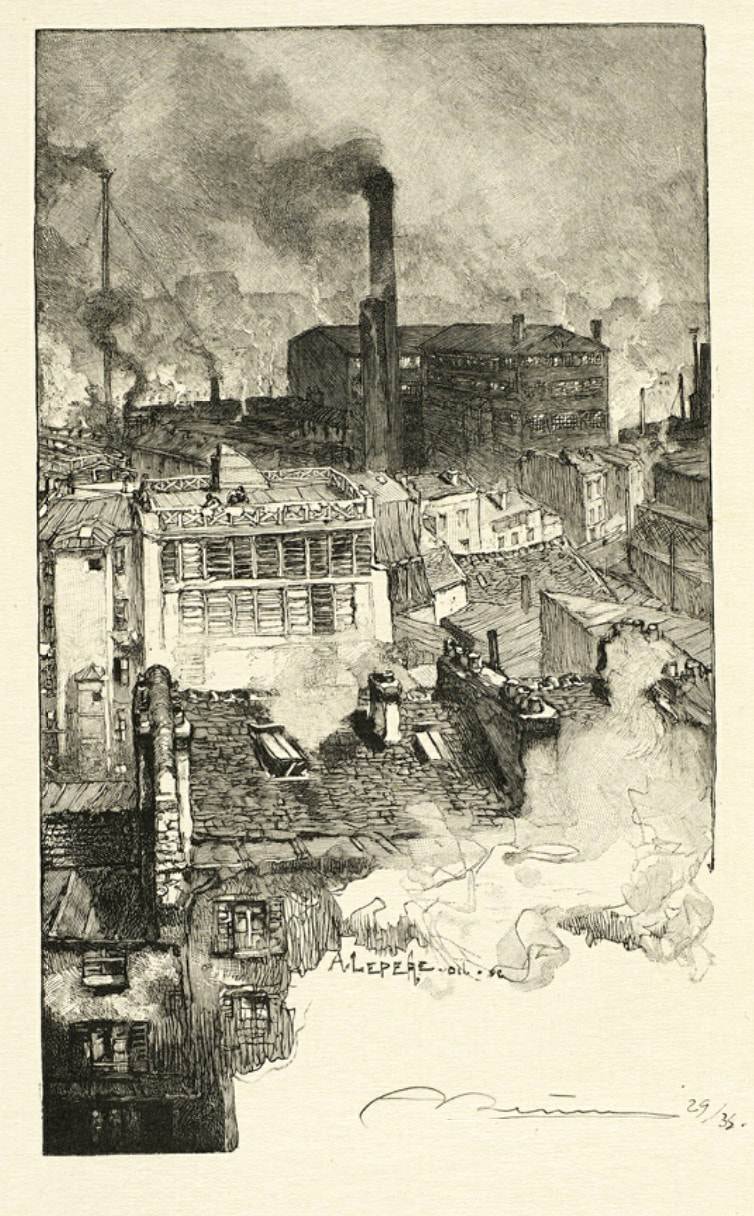

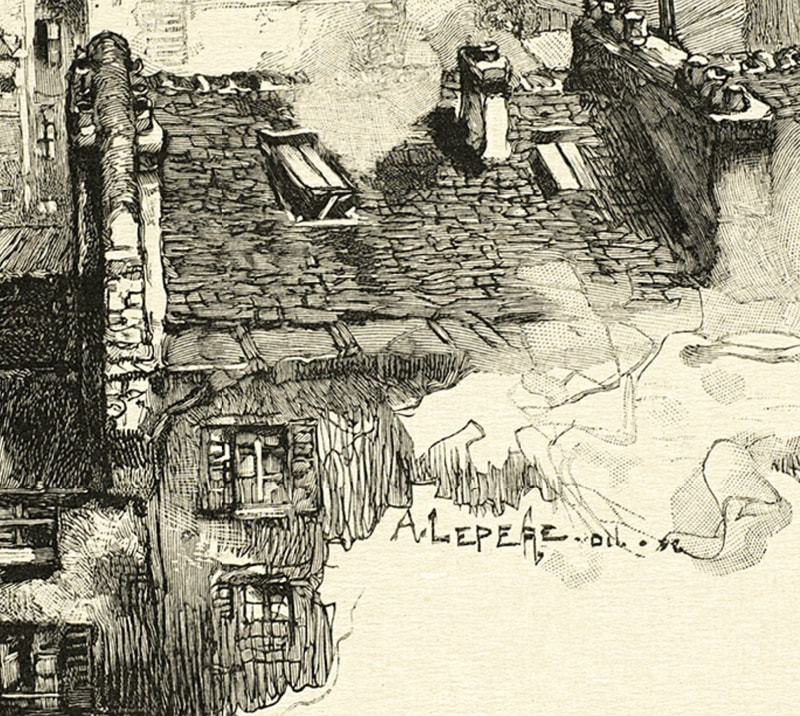

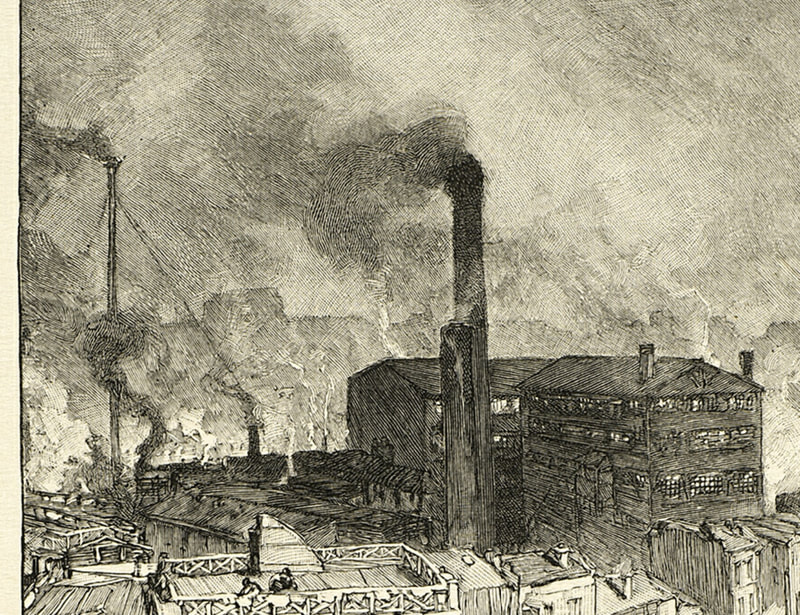

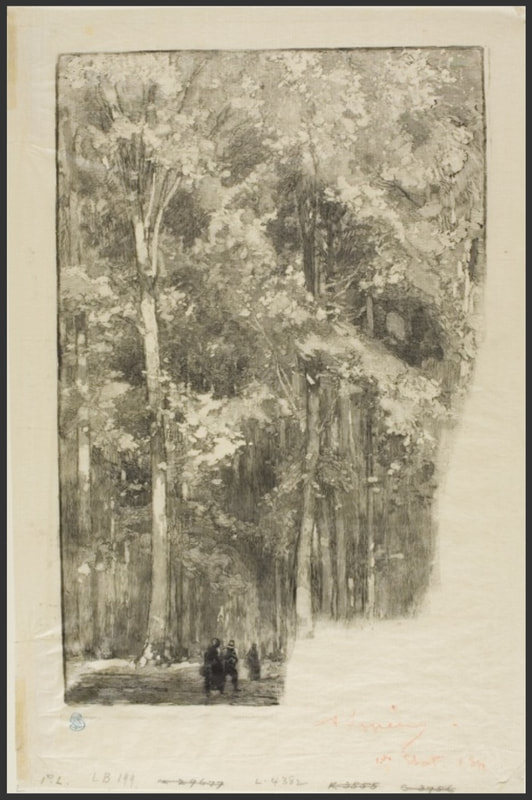

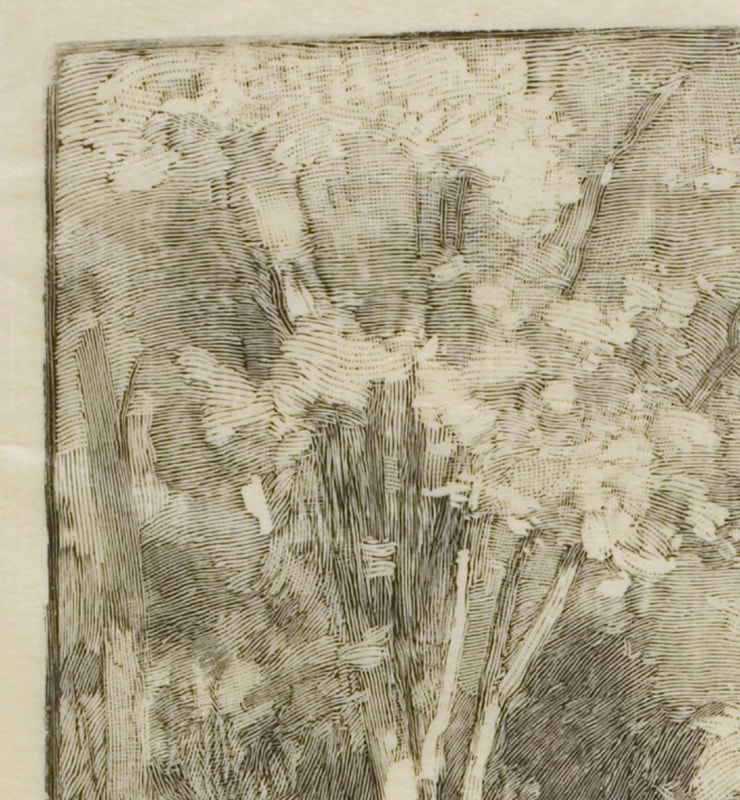

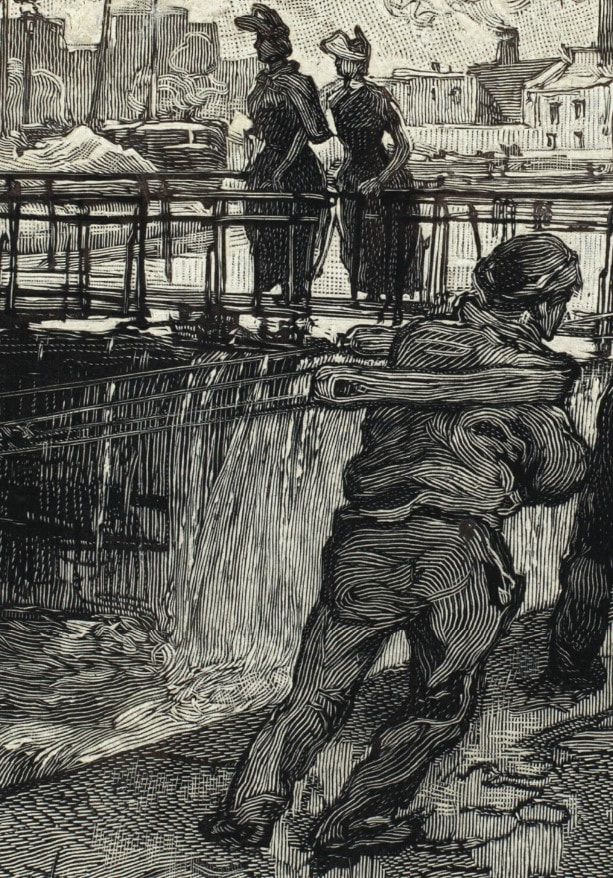

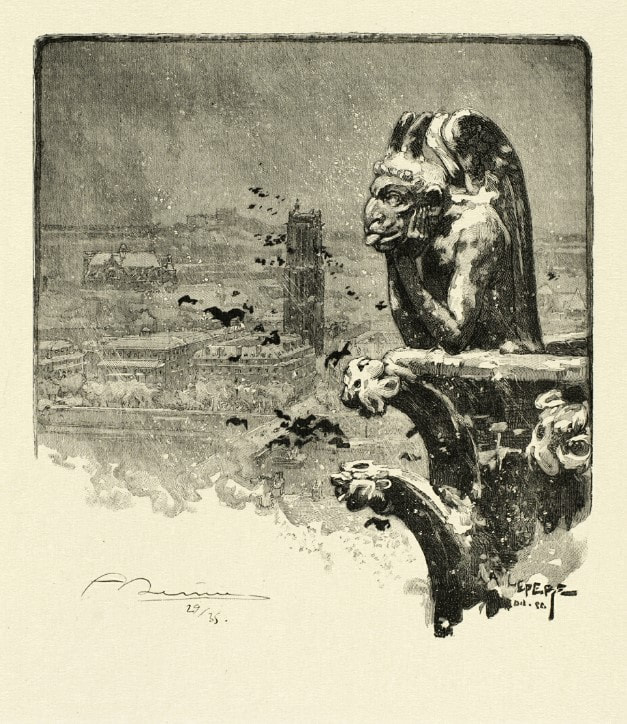

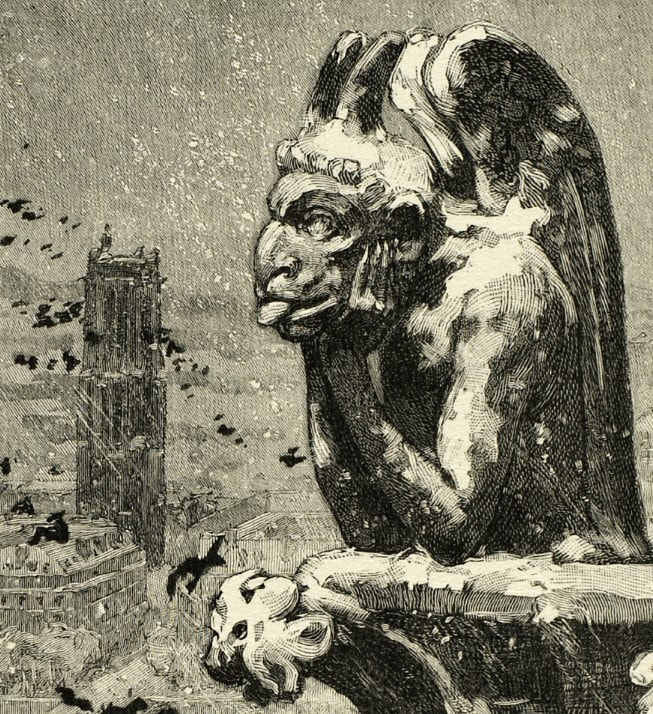

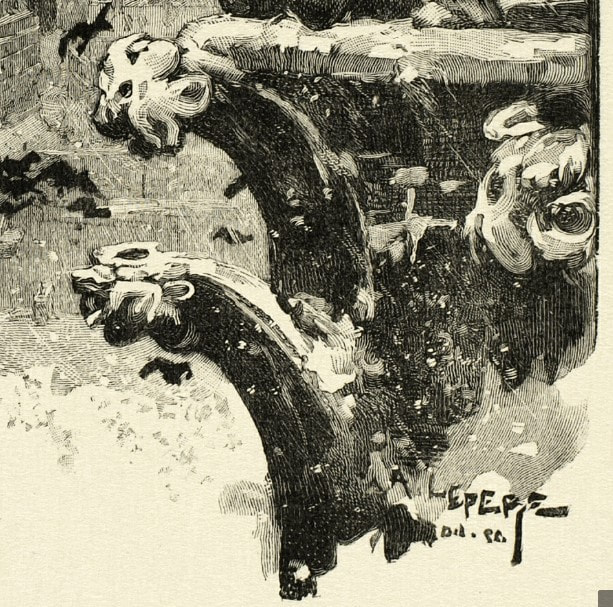

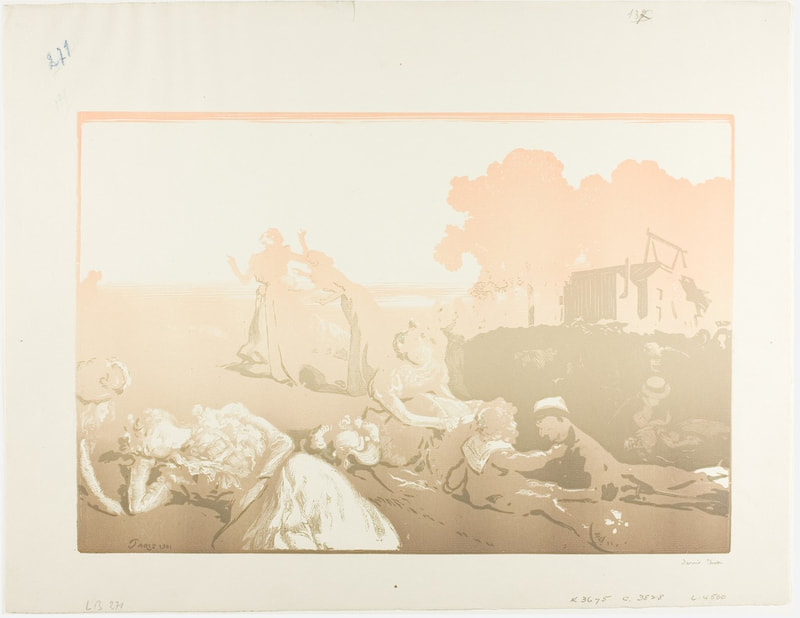

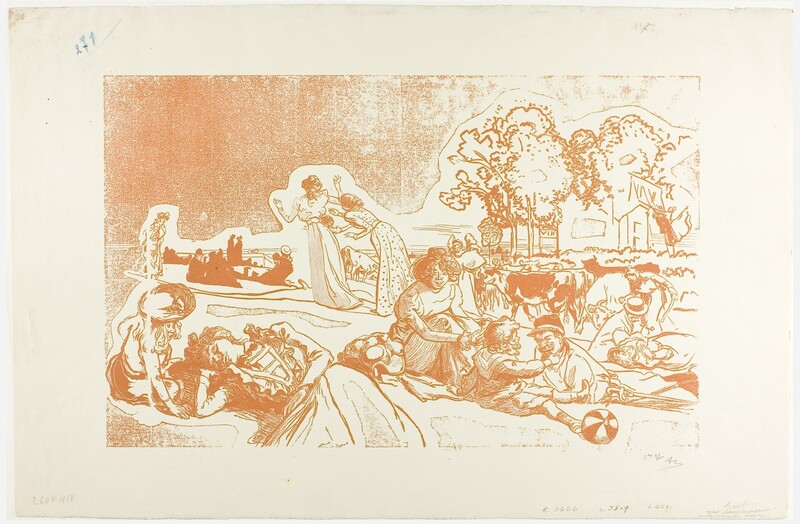

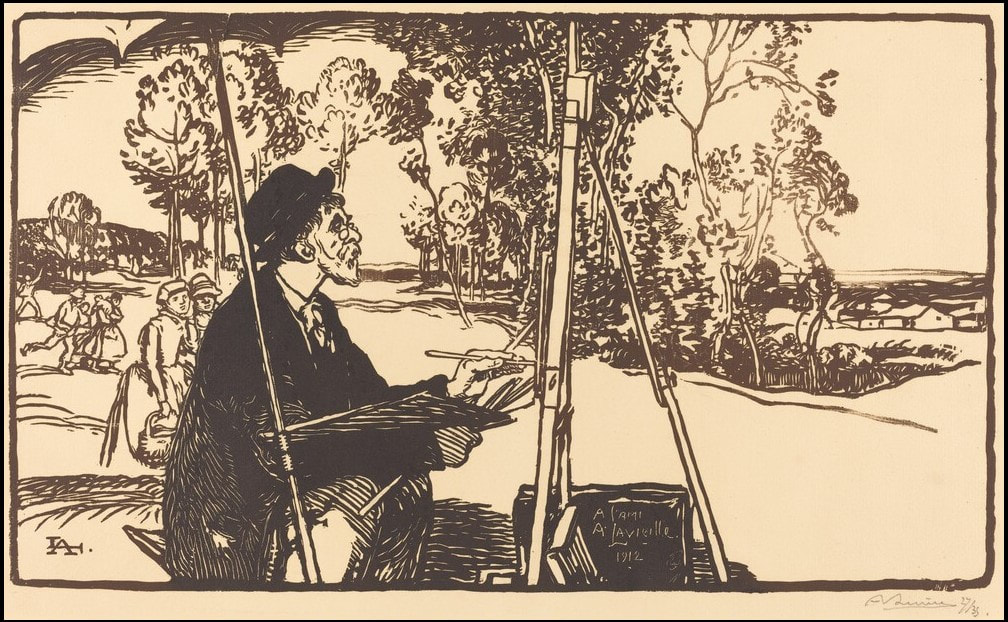

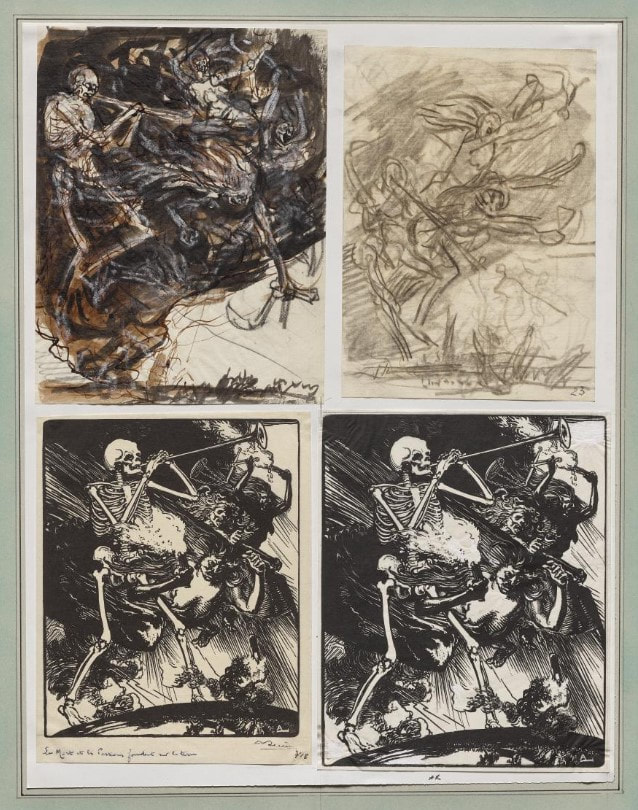

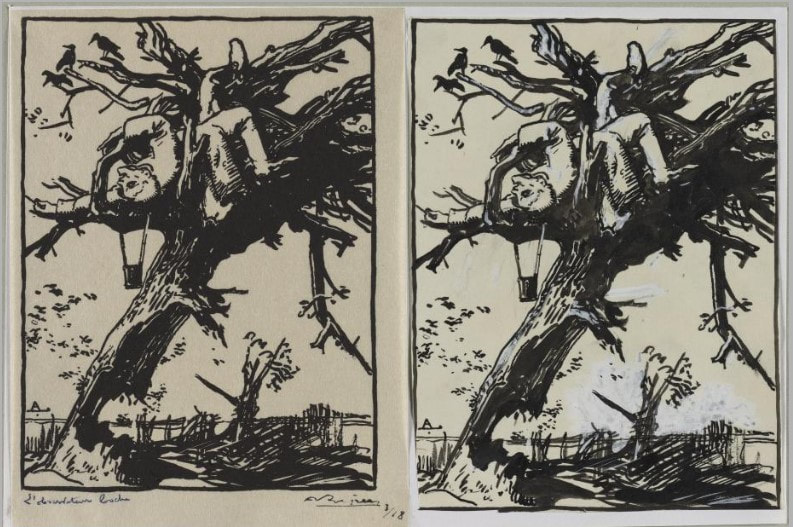

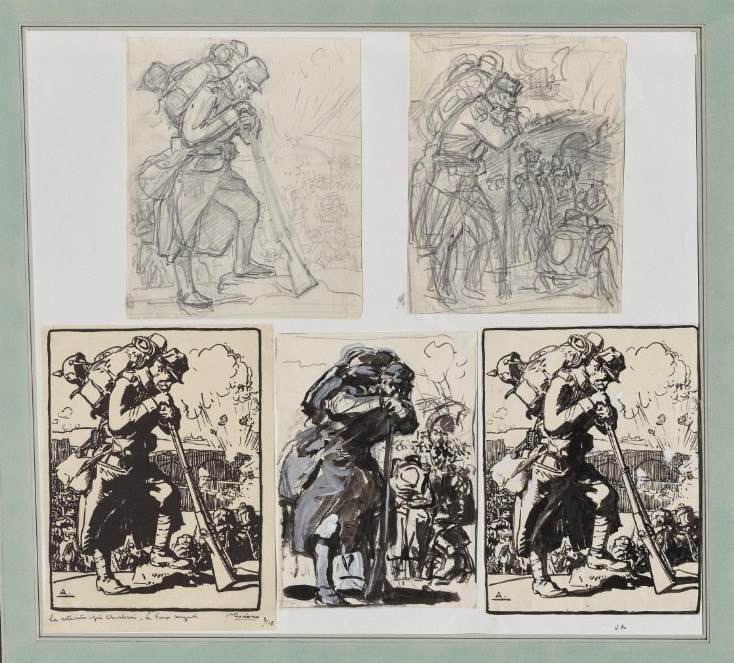

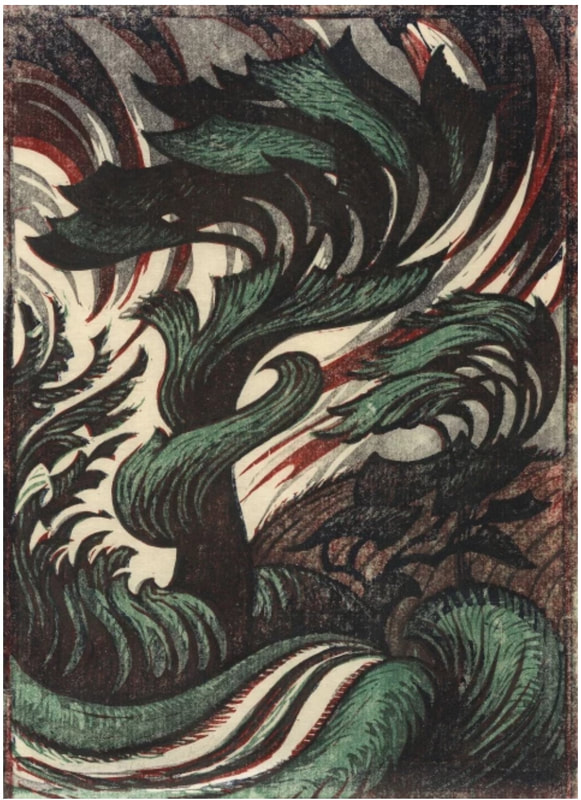

A contemporary critic wrote of his frustration: “To the world, and especially the foreign world, the name of Lepère is chiefly familiar from his engravings and notably his woodcuts. The artist himself, however, considered these merely as auxiliary to his oils. ‘I am, above all, a painter’, he would say remindfully if a suggestion were made to attribute preeminence to his plates and blocks. For originally he had taken up engraving as a breadwinning makeshift, and it was much against his wish that the popularity they won robbed him of the time he would for choice have spent at the easel.” Well, you can’t control what the viewer thinks or likes, can you? Lucky for us, Lepère was an amazing printmaker. He did it all: wood engraving, woodcut, etching, lithograph. Mostly the subjects are everyday life in and around Paris. They range from laundresses and dock workers to a new middle class enjoying a day off in the park. Today, as we are just emerging from a year in lockdown, these Parisian scenes are a balm to my soul. I can’t wait to get on a plane and go enjoy a croissant with my cafe au lait. I happen to love Lepère’s wood engravings, especially those printed on an almost translucent Japanese tissue paper. So delicate. They always stunned students in the study room. I’d hand them a loop and tell them to look at, say, the smoke emanating from a smokestack and their jaws would drop. I included details here, grabbed as best as I could from the web. Take a look at some of them. And there’s a wood block, too. Amazing mark making. Don't miss the Cleveland Museum's sets of studies and the final woodcut toward the end. These all date to 1914 and appropriately reflect the turmoil of World War I. Bucolic escapes are no more. Lepère died toward the end of the war.

0 Comments

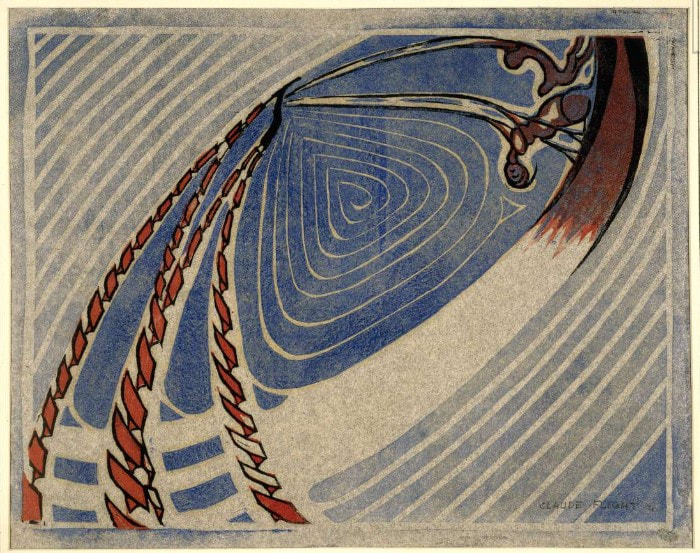

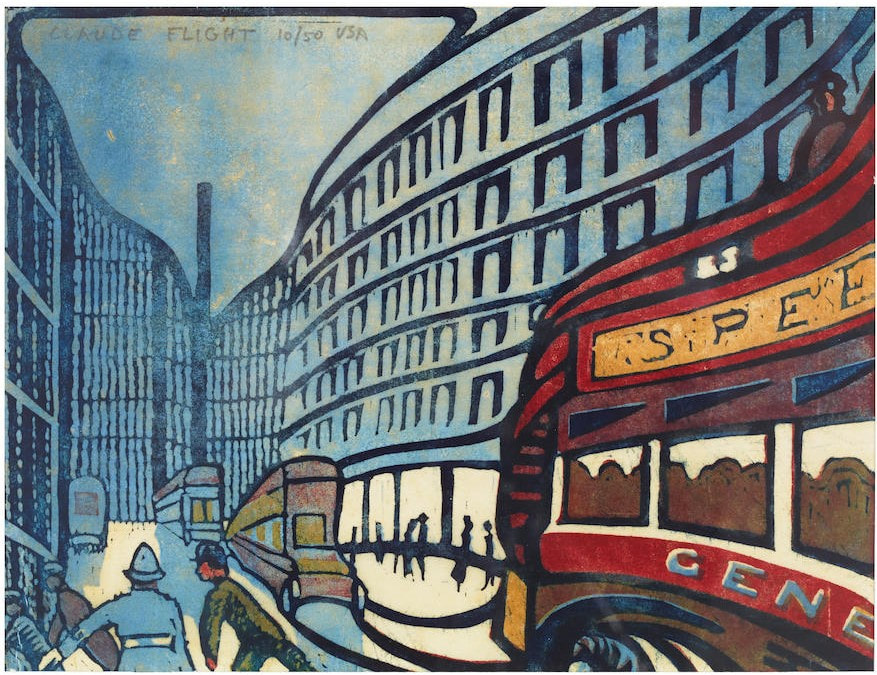

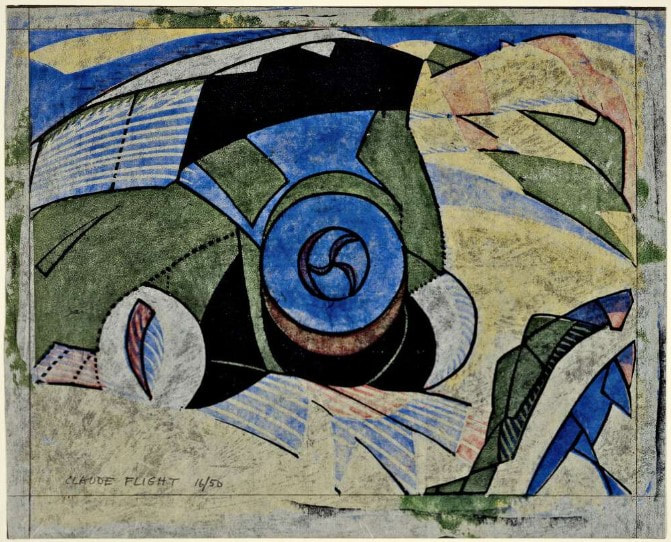

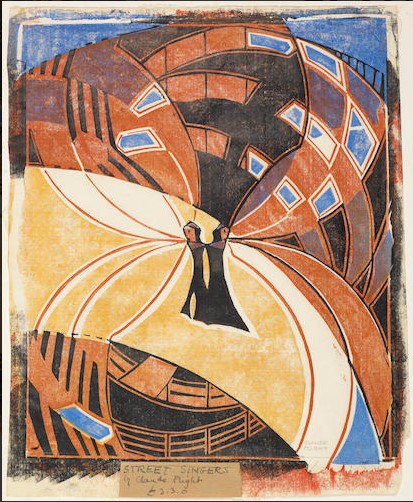

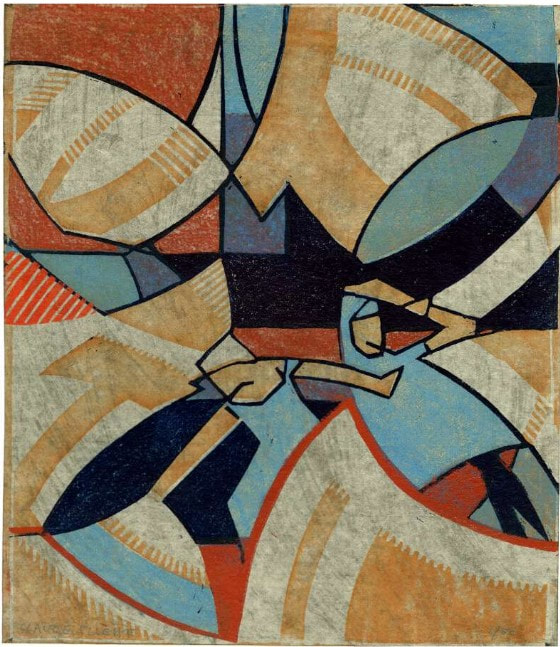

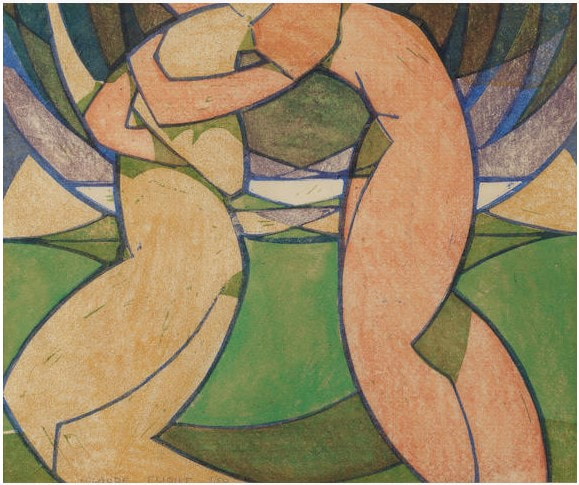

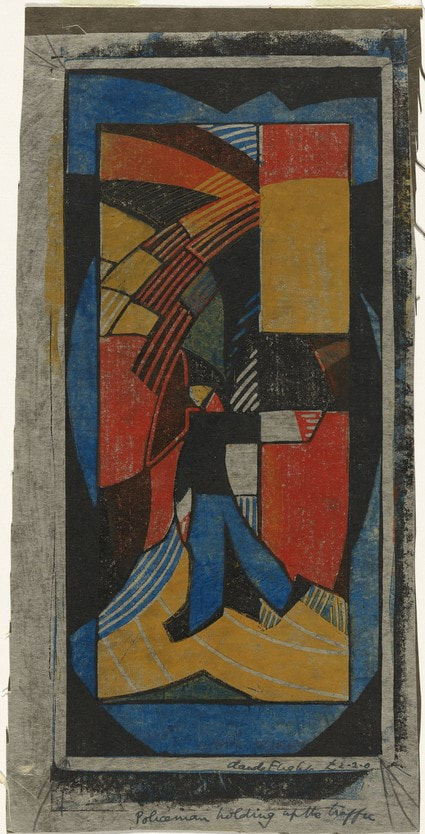

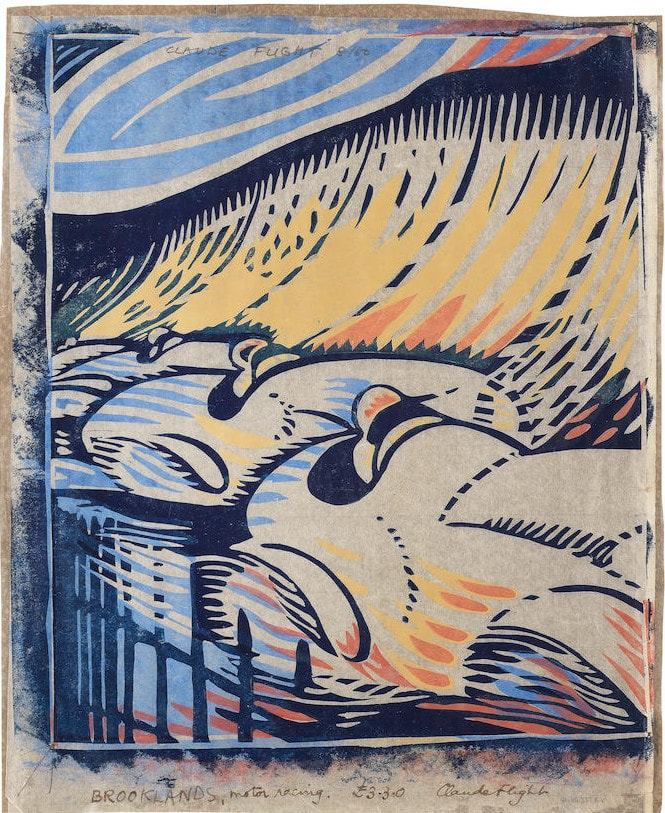

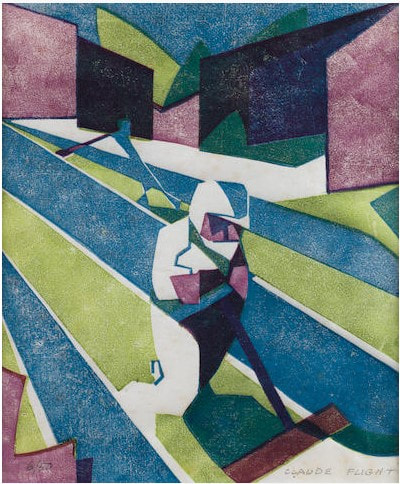

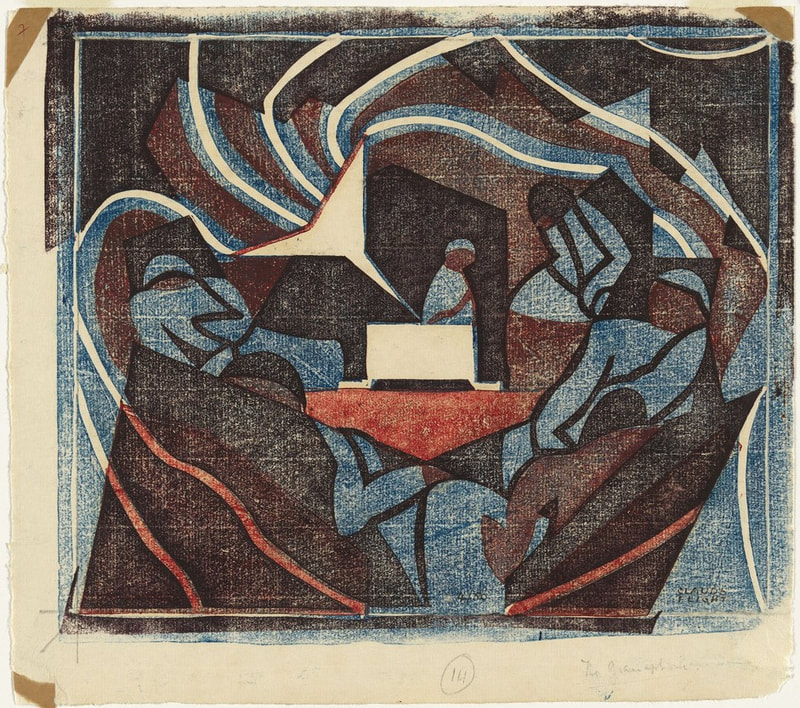

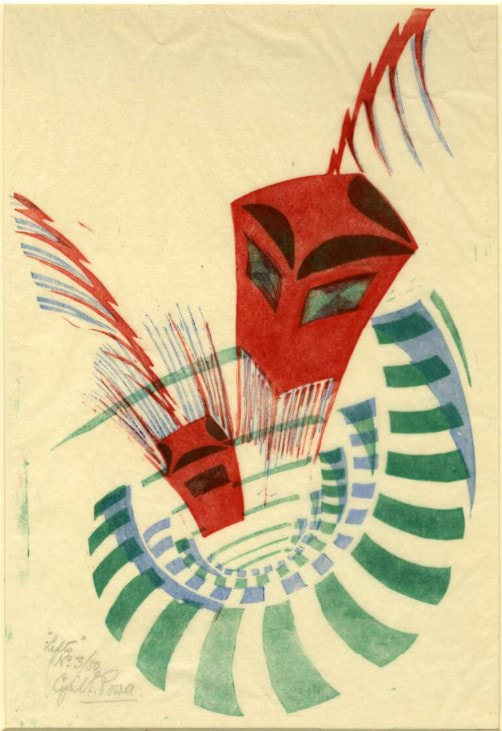

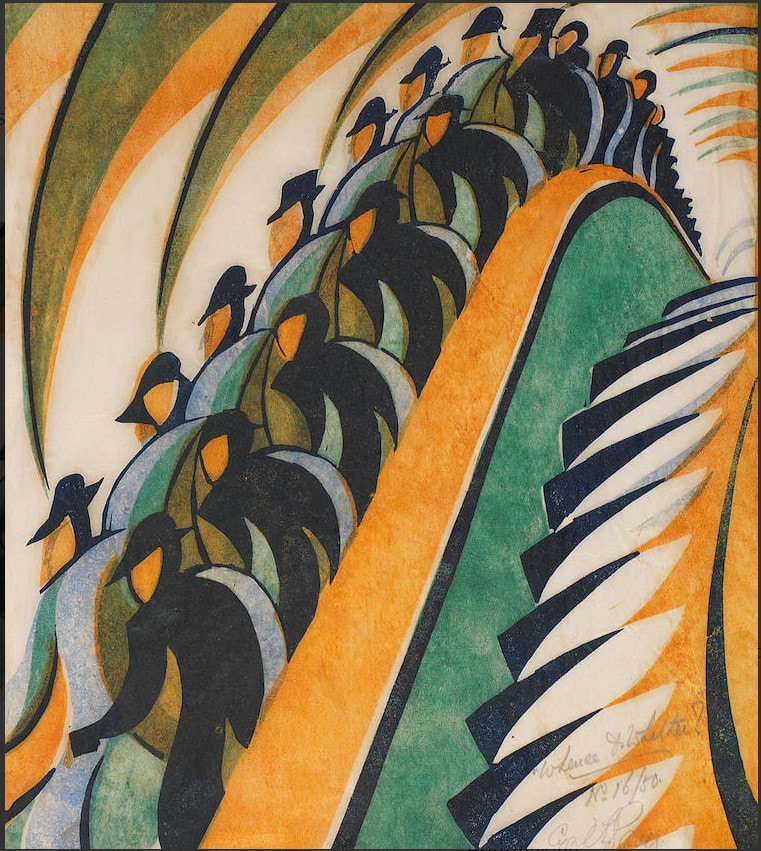

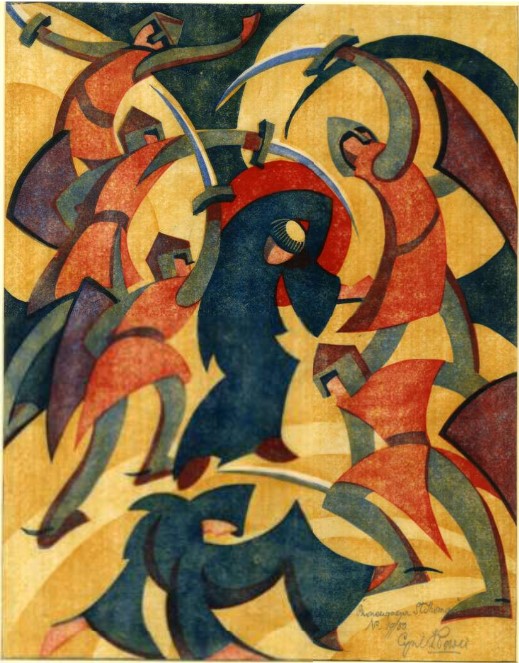

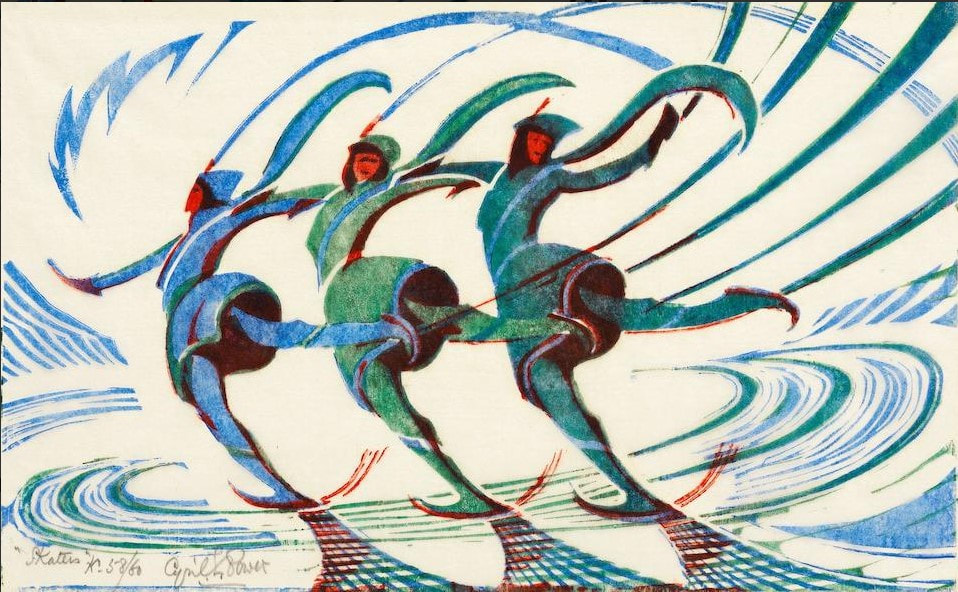

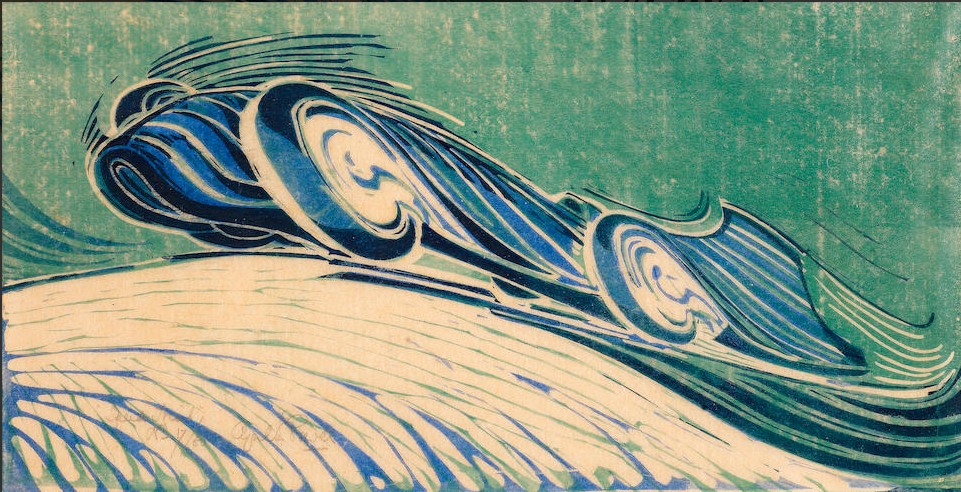

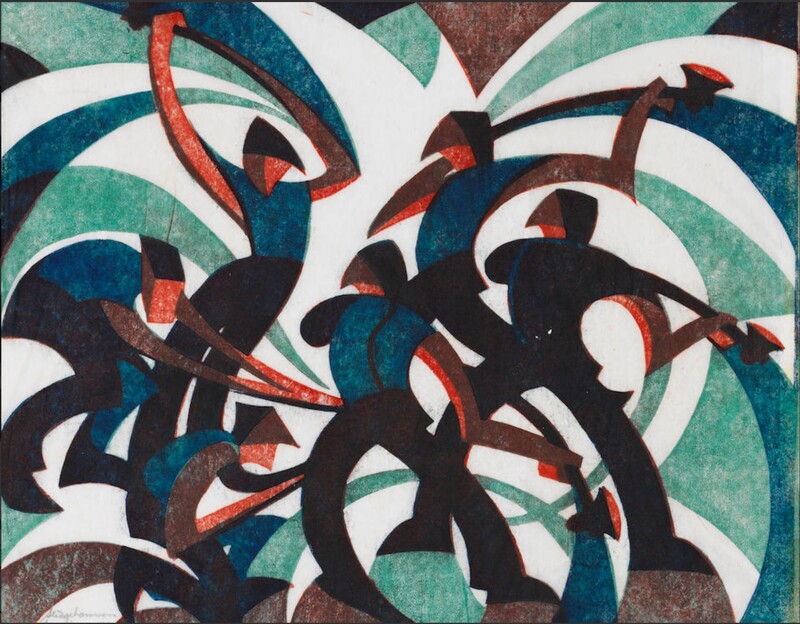

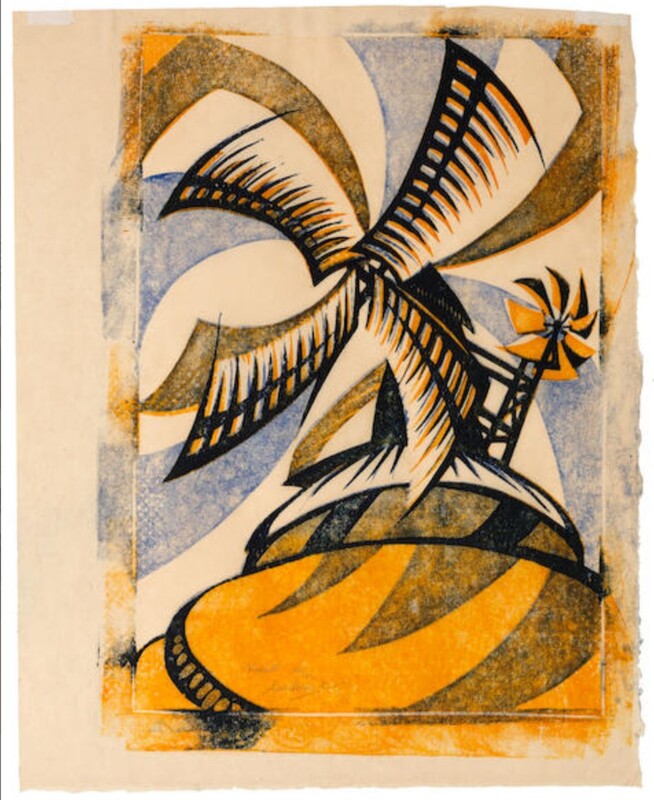

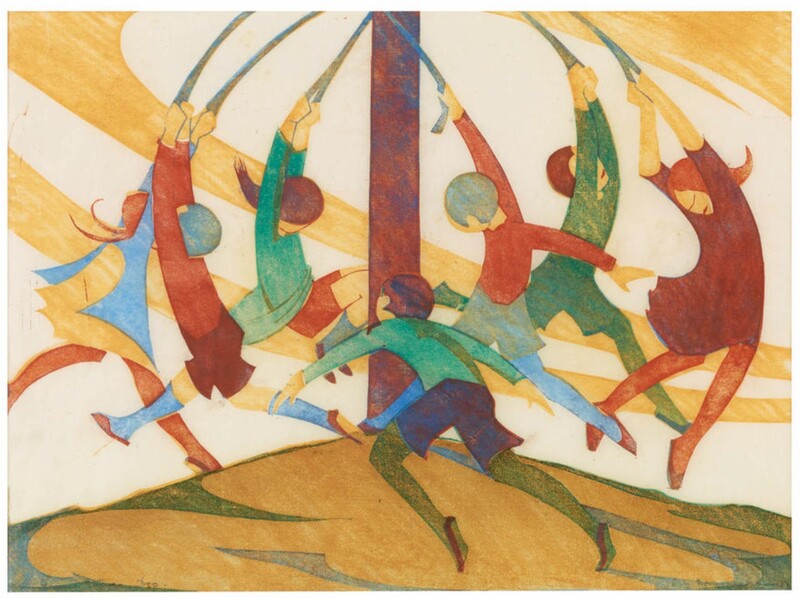

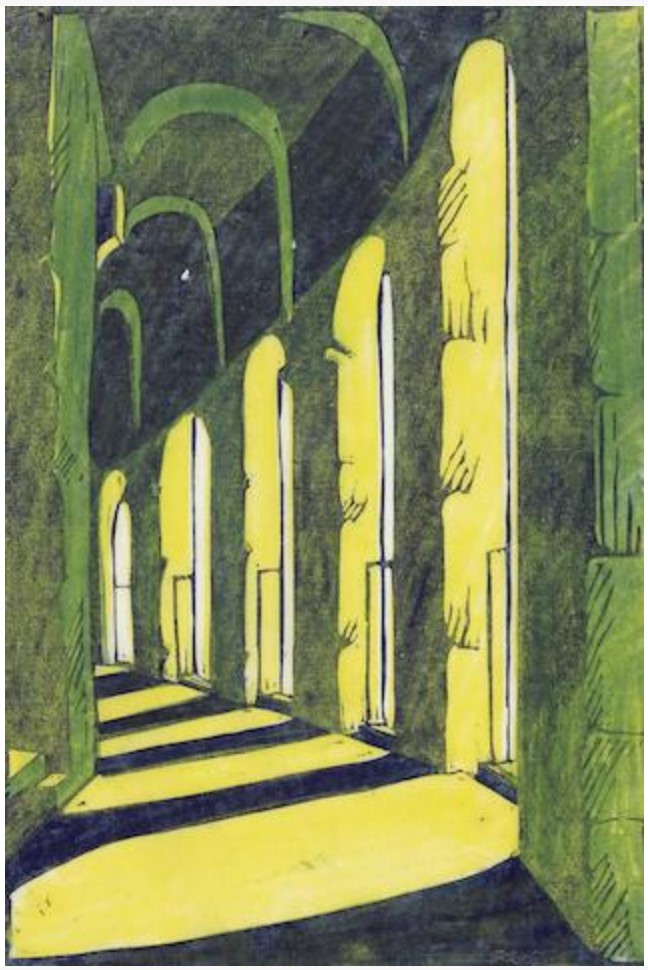

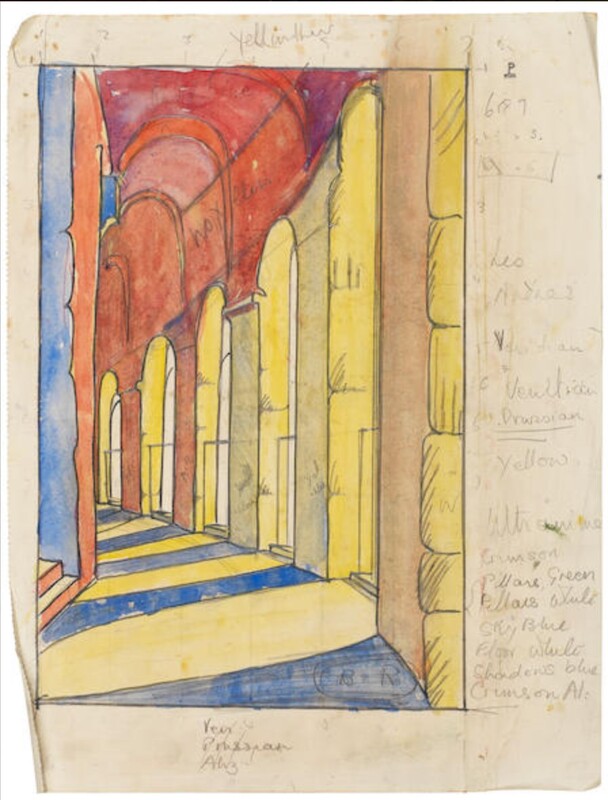

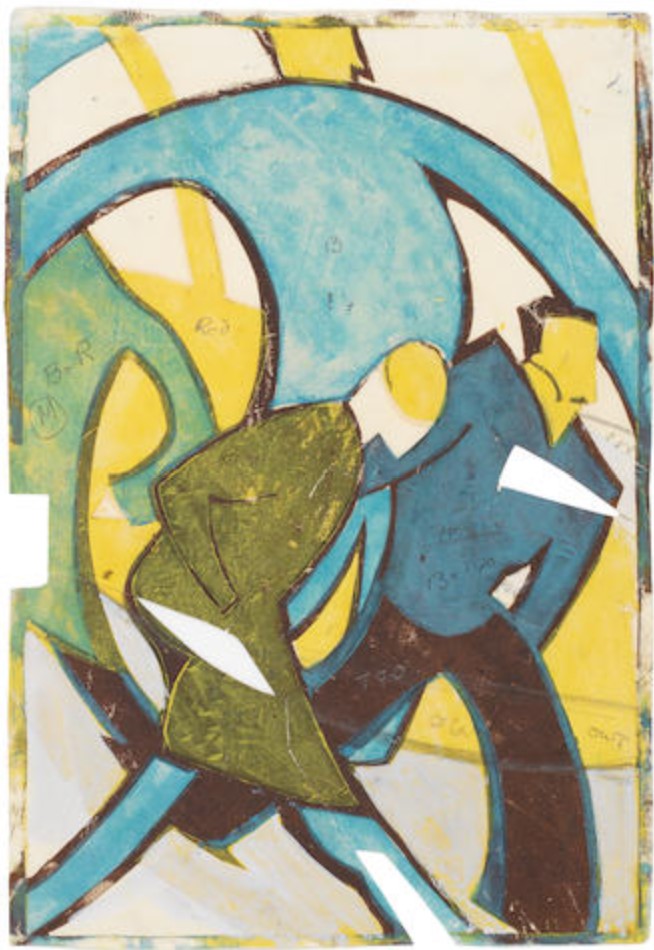

Ann Shafer Here’s the final Grosvenor School post (for now, anyway), featuring the man who started it all, Claude Flight. I find it fascinating that his work kinda gets at the aesthetic we have come to expect from the group, but many of his prints are wholly different. I would love to have been a fly on the wall in the studio, to see who developed what first, who picked it up, and who pushed who, etc. Imagine being surrounded by so much color and motion.

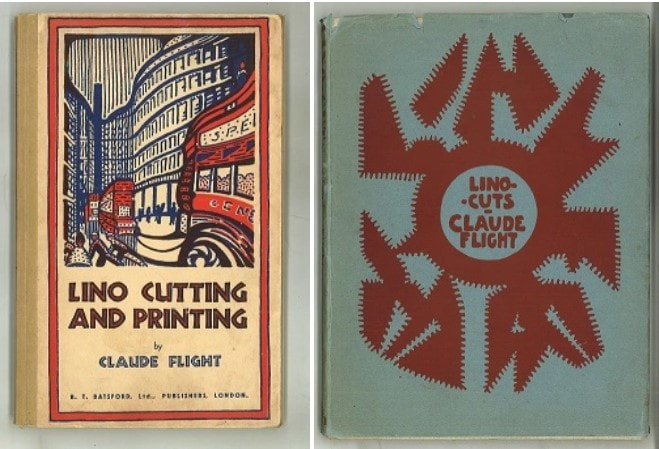

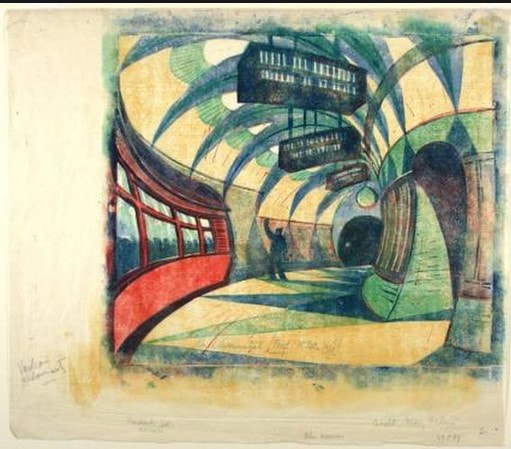

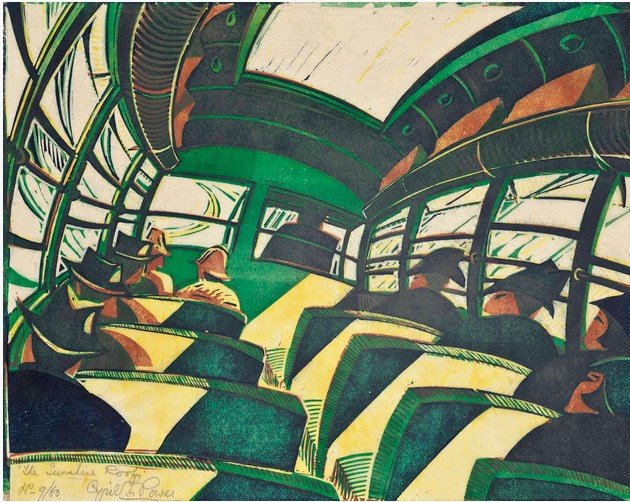

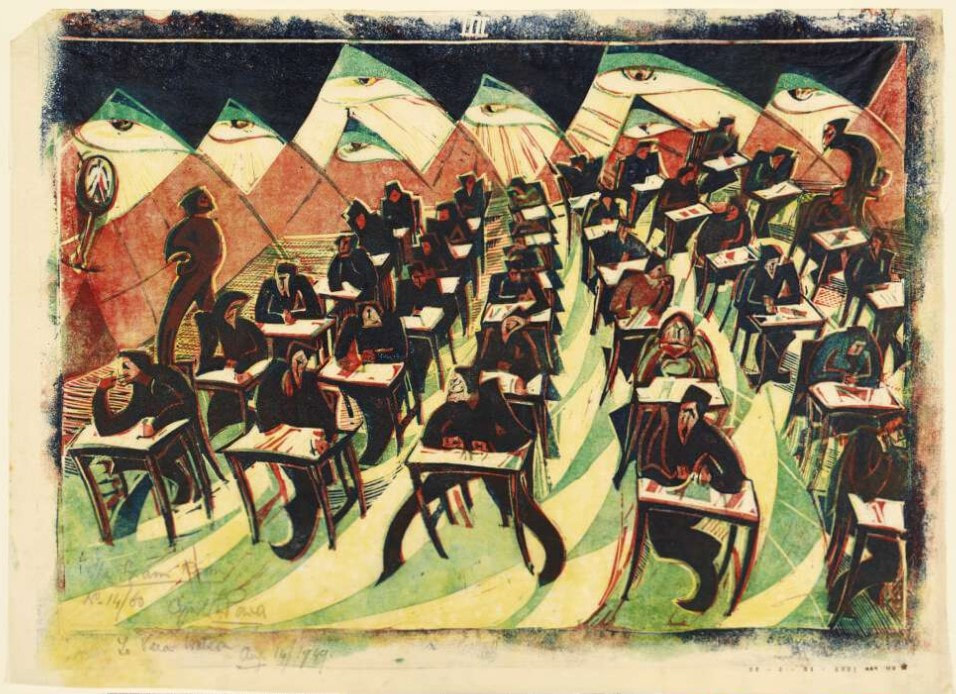

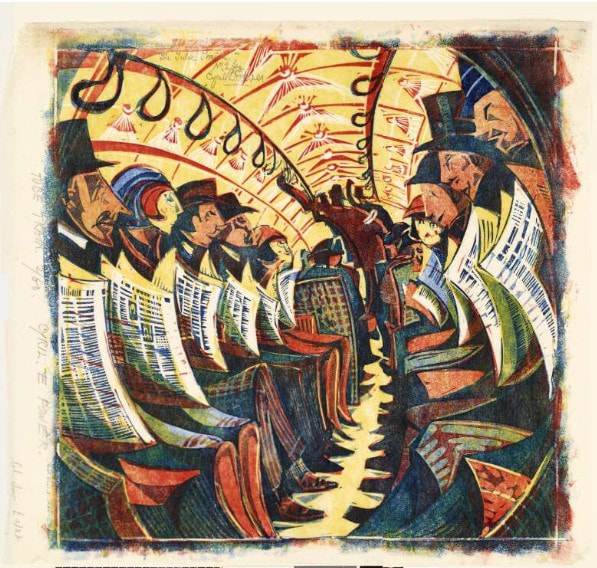

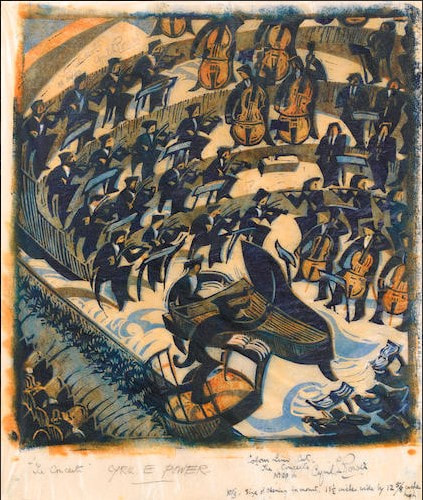

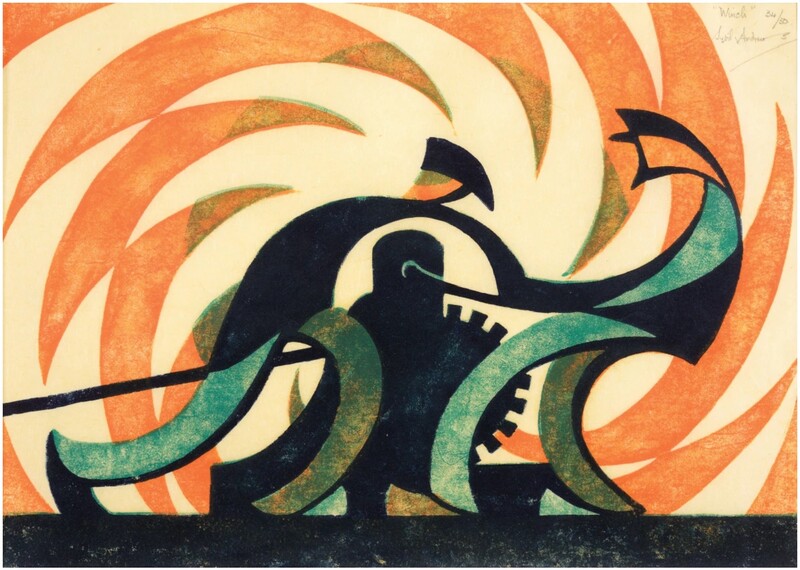

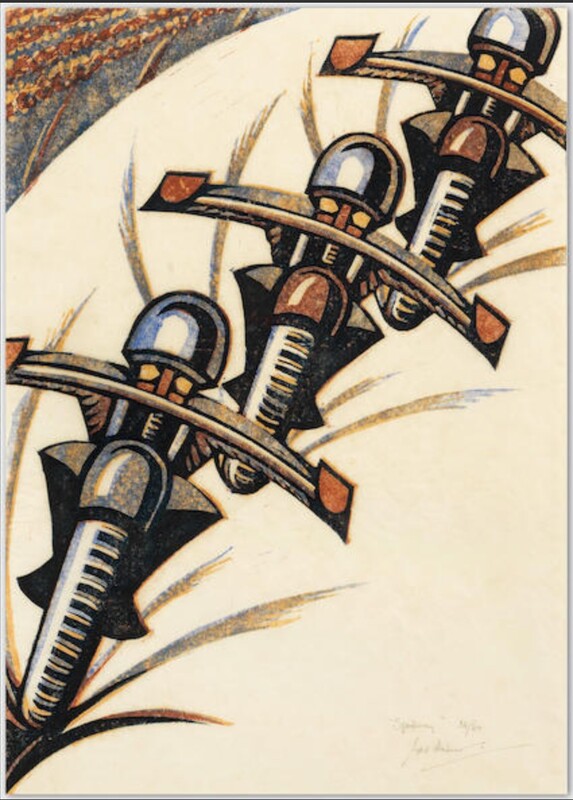

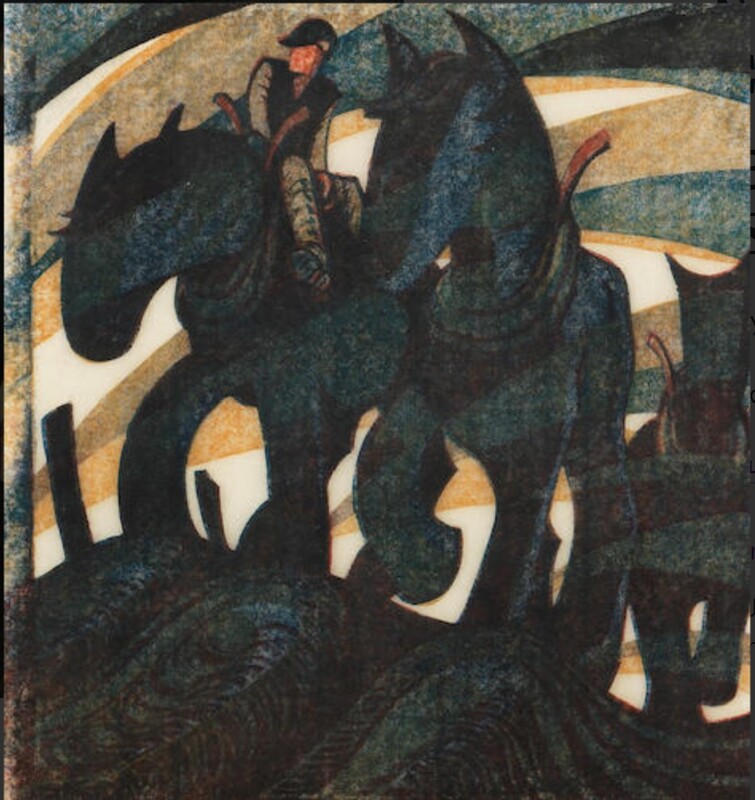

This is what I love about printmaking. Because of the need for shared equipment and supplies, artists work together, side-by-side with like-minded artists. All this togetherness might lead to friendly competition or alignment of sentiment, and the results might lead to unplanned and exciting discoveries. Flight took up linoleum cutting as early as 1919 and fell in love with it. It was easy to procure and not so costly, plus its ease of cutting seemed perfect as a route to making it possible for the masses to be exposed to art. More, cheaper, faster. He saw in it the potentiality of a truly democratic art form. Sounds a little like previous movements that attempted to bring art into every home, like William Morris' arts and crafts movement, doesn't it? Just in an updated, modern way. Here's Claude Flight. Ann Shafer Recently I shared a post about Sybil Andrews, which seemed to strike a chord if the number of likes and shares is any indication. Her multi-color, multi-block linoleum cuts, like those of her compatriot Grosvenor School artists, celebrated modern life in 1930s England. Today we’re looking at linoleum cuts by Andrews’ close friend and studio mate Cyril Power, who focused mostly on modes transportation, particularly the London Underground.

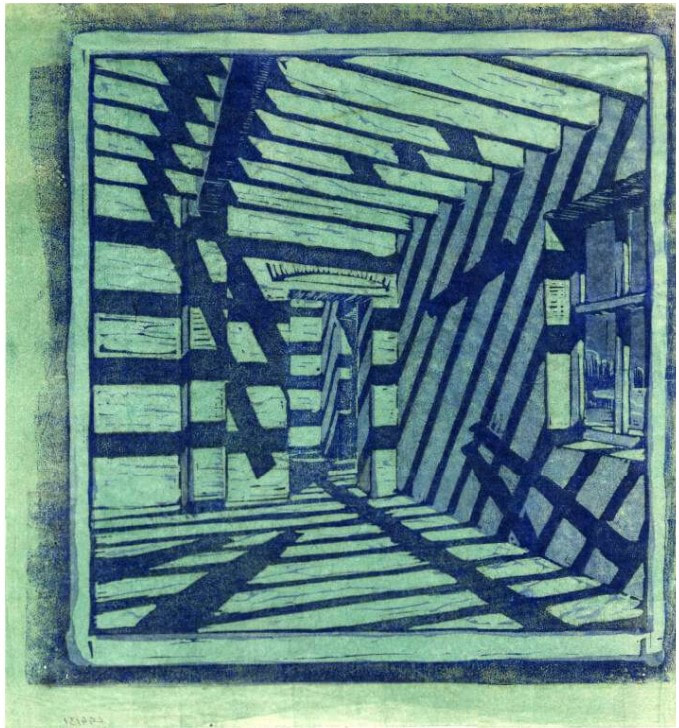

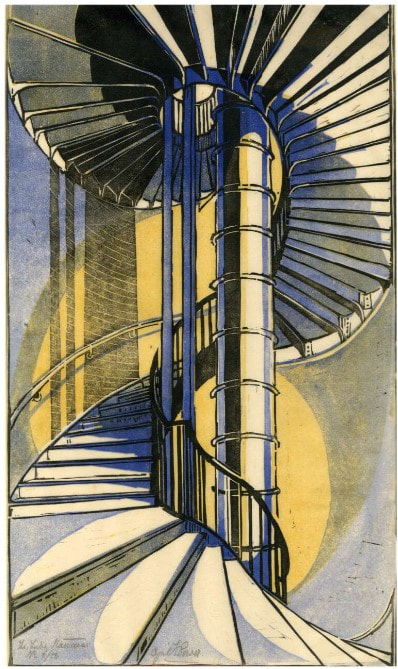

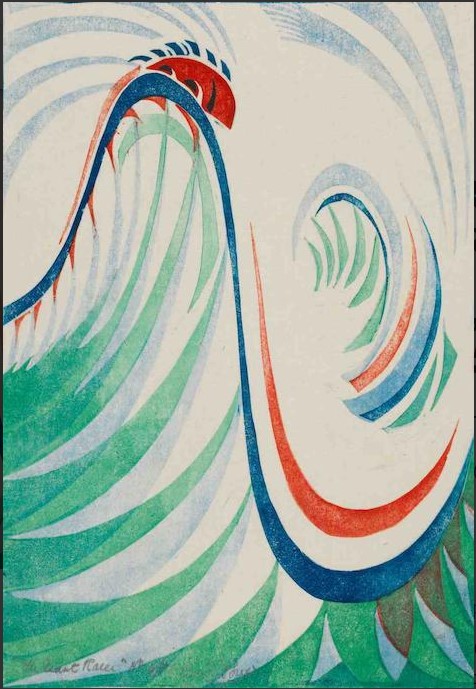

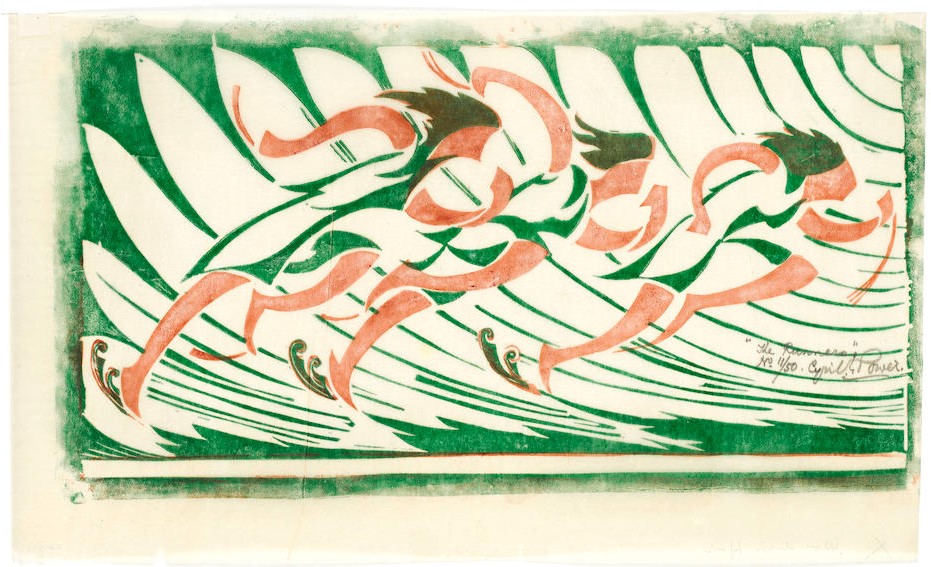

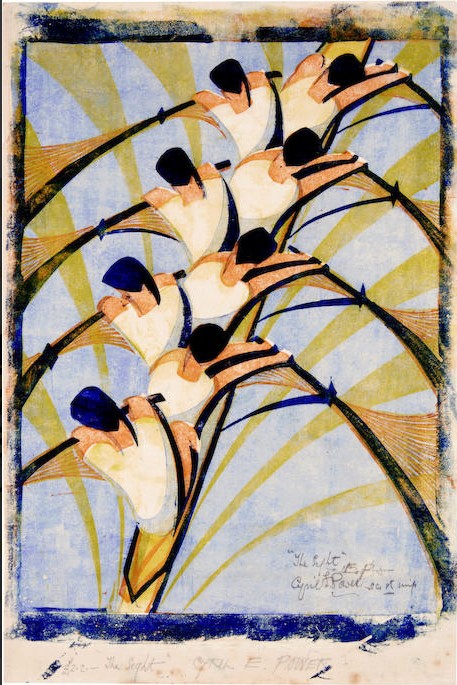

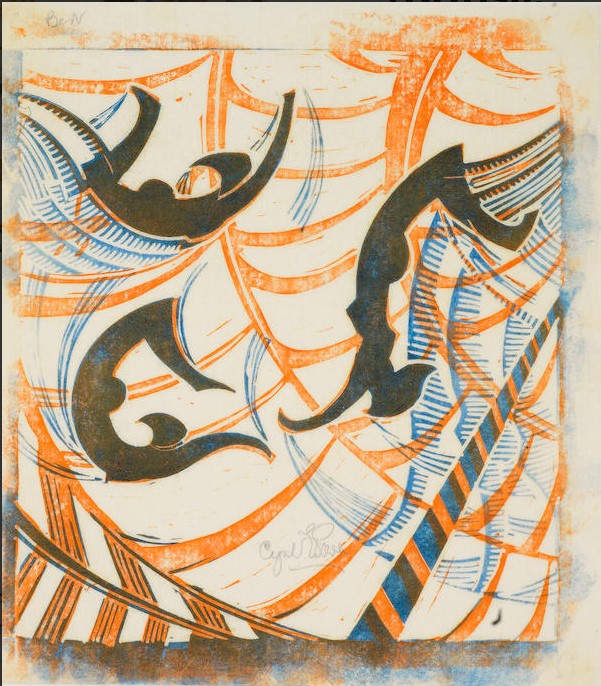

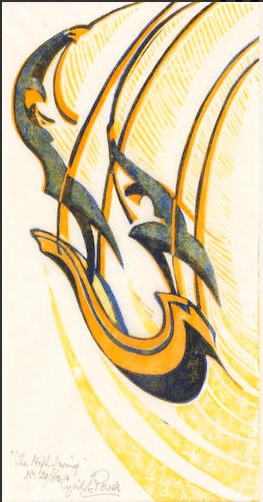

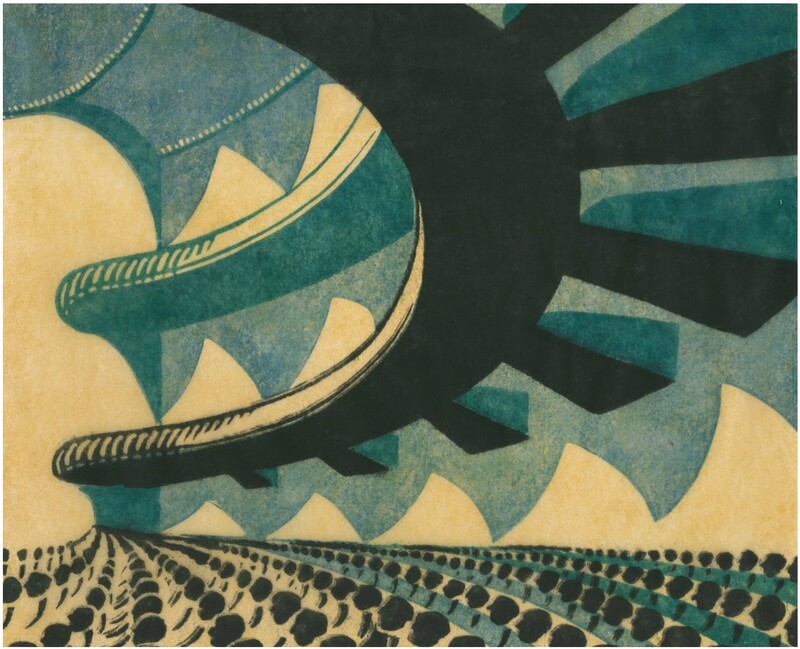

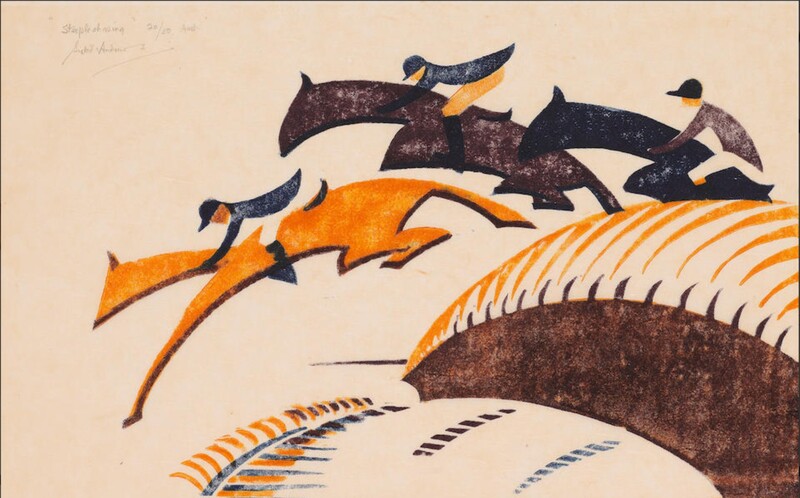

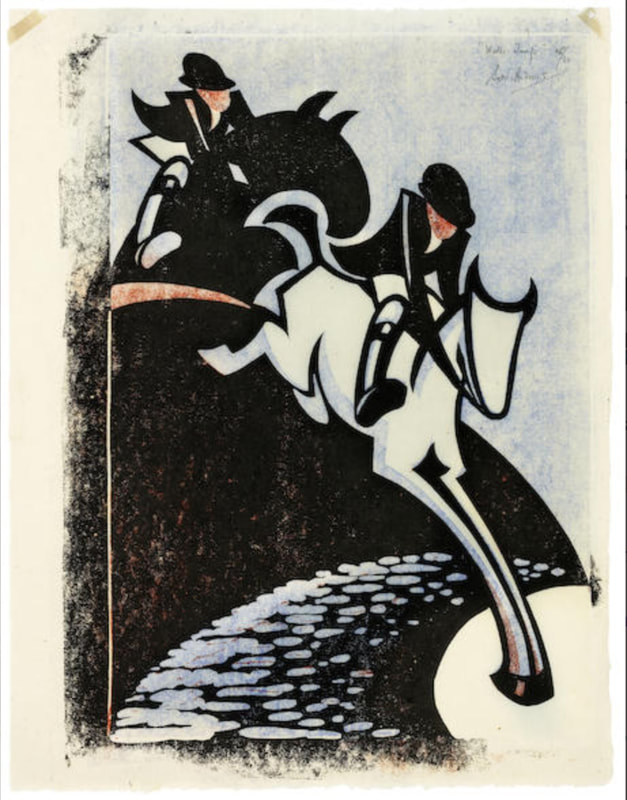

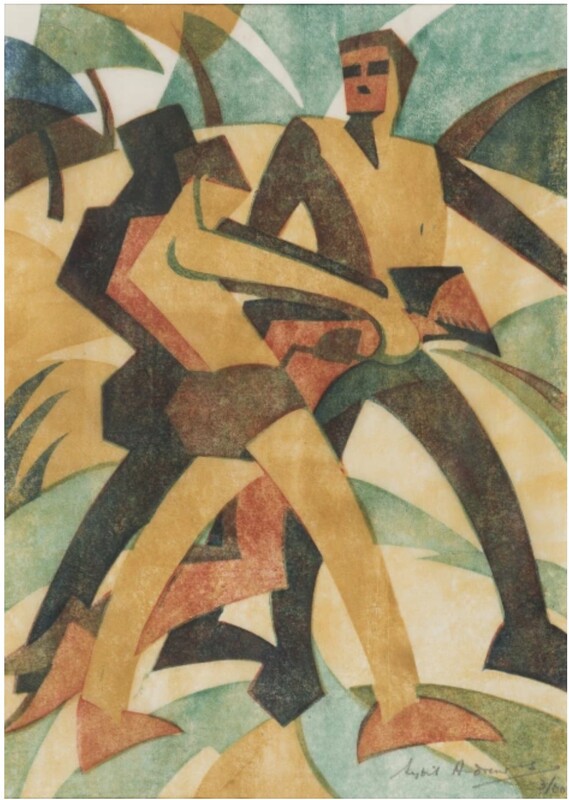

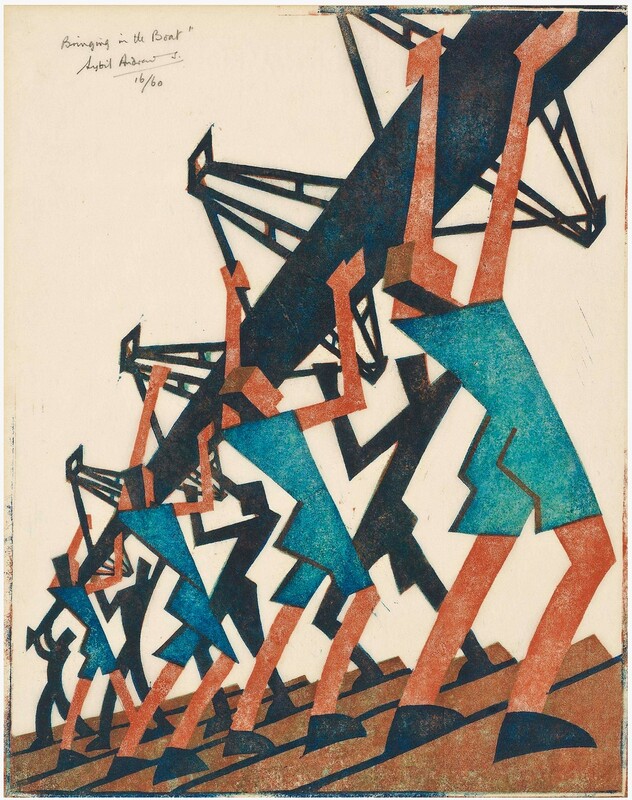

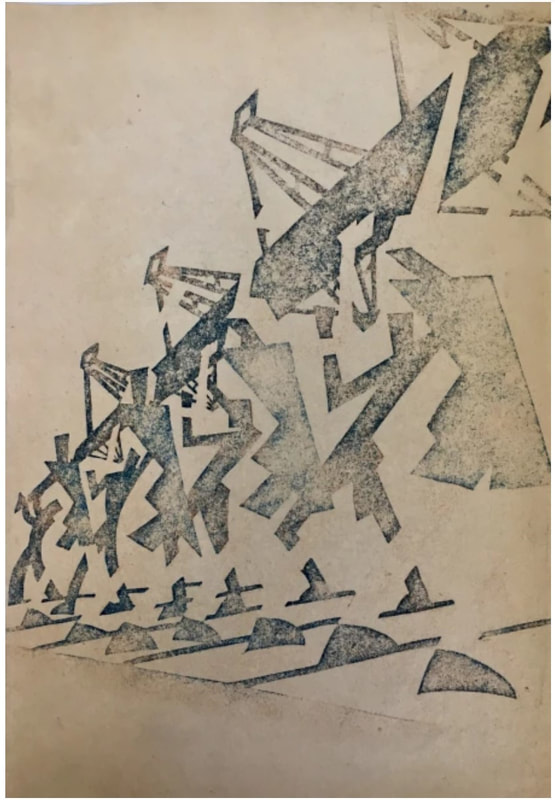

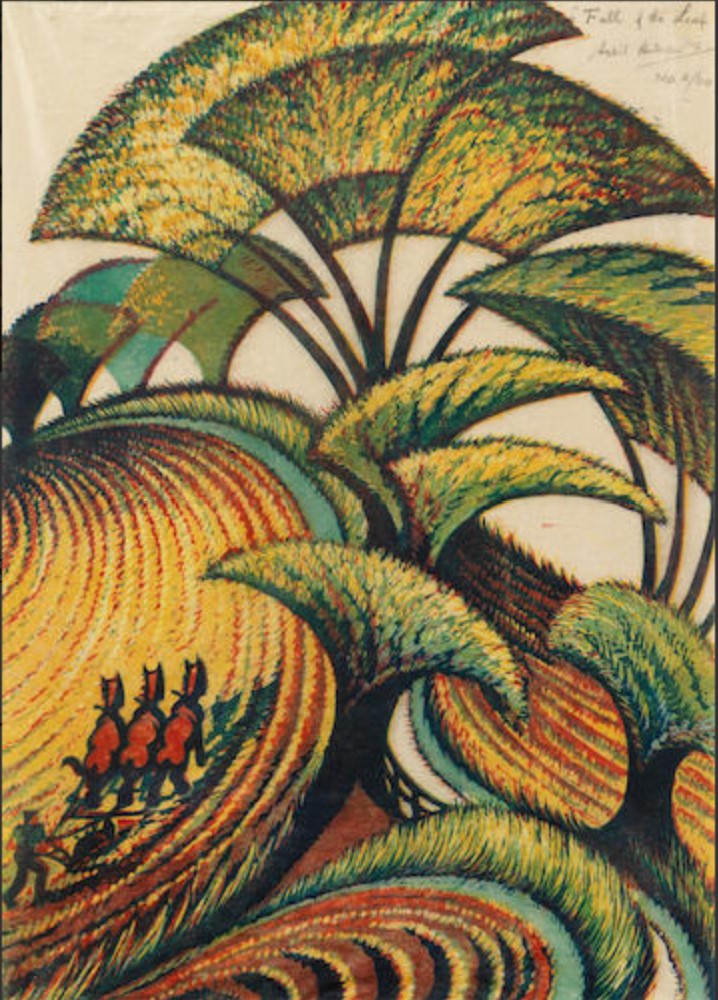

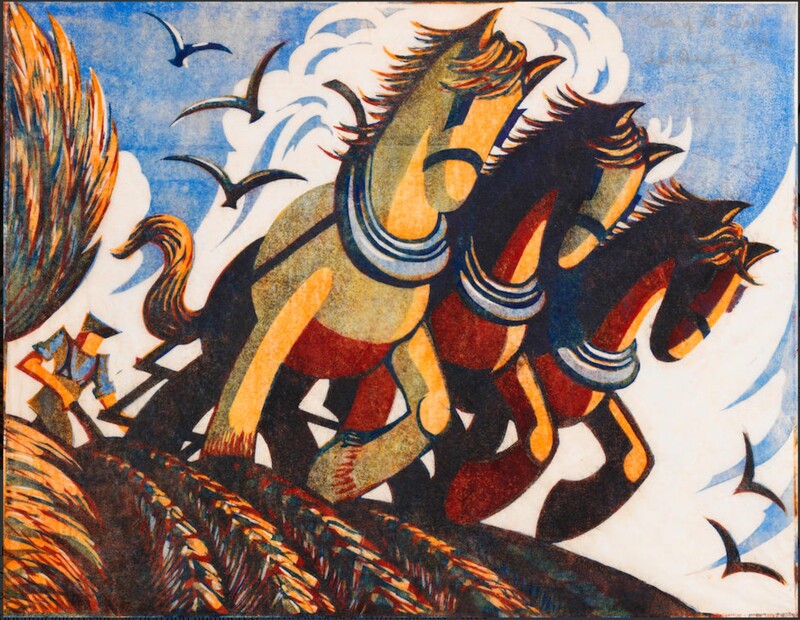

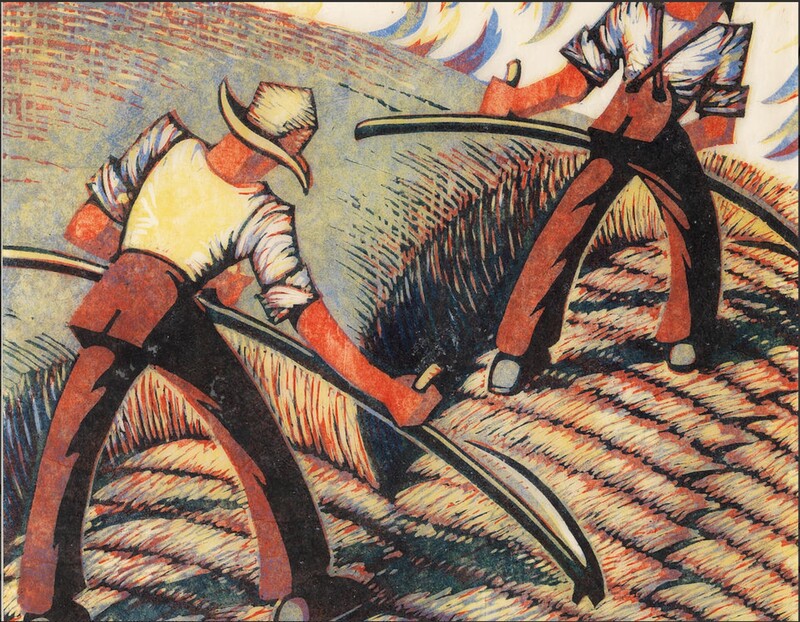

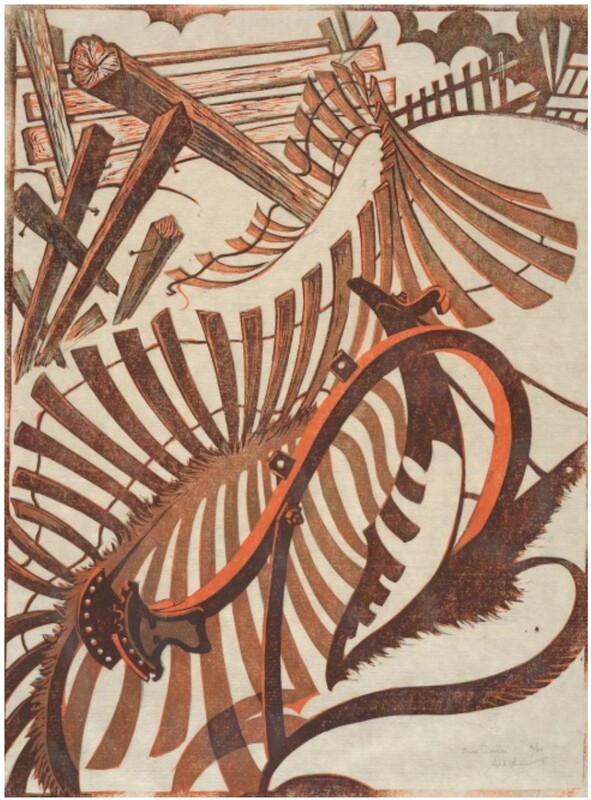

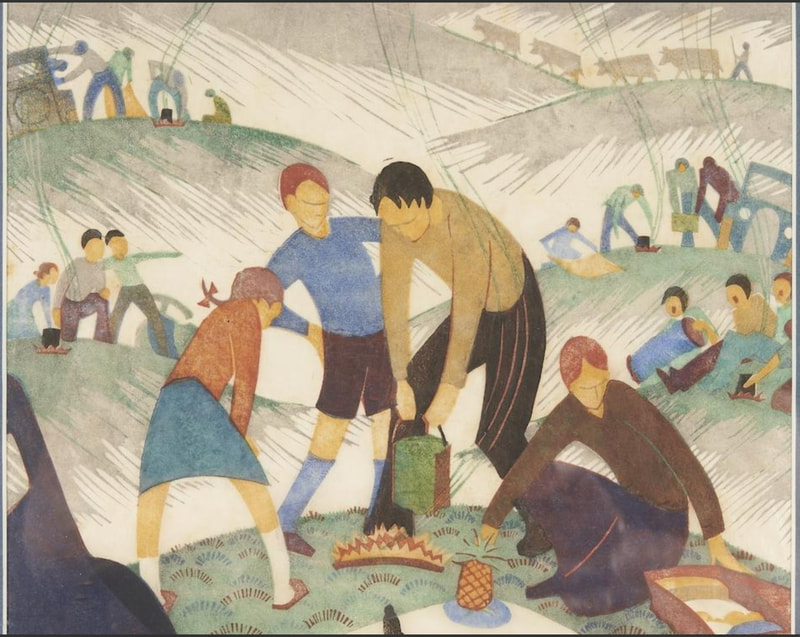

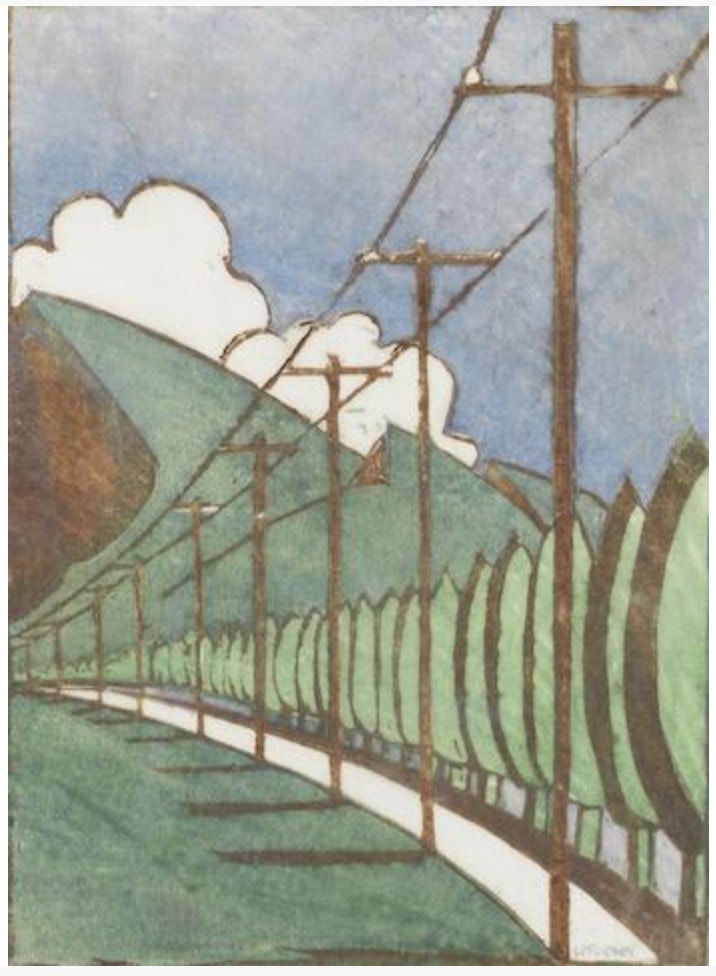

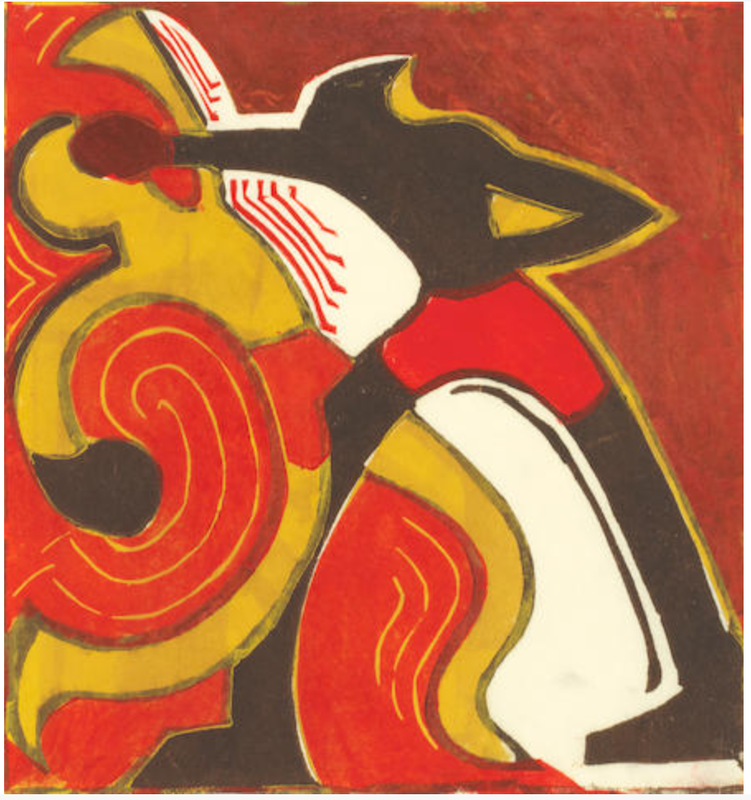

Like Andrews, Power was on the staff at the Grosvenor School when it was founded by Iain Macnab and Claude Flight in 1925. The latter was responsible for the growing interest in multi-color, multi-block linoleum cuts celebrating the speed of modernity. Power himself was a lecturer at the school. He was also a noted scholar of architecture and penned the three-volume A History of English Mediaeval Architecture, which included 424 of his own illustrations and designs. But he’s best known for the linoleum cuts he made alongside Andrews and Flight. Andrews and Power shared a studio for twenty years, giving it up in 1938 (they were both married to other people). Power served at home during the war as a surveyor for a Heavy Rescue Squad (he had also served in World War I), and after the war turned primarily to painting in oils. He died at 78 in 1951. Even when Power’s images are of static, stable things, they feel as if they are in motion. I might even say that he captures motion and potential energy better than Andrews. There’s a reason their compositions are among the best known coming out of the Grosvenor School. They were two of the best. See if you agree. Ann Shafer I love Sybil Andrews’ sensibility. Like Ursula Fookes and Ethel Spowers, who we met recently, Andrews, no surprise, was a part of the Grosvenor School of artists focused on multi-block color linoleum cuts exploring the speed of urban contemporary life primarily during the 1930s in England. I love that she explores speed literally through images of raceways and steeplechases. But she also does something surprising by focusing on rural life and agriculture in that same modernist mode. A bit antithetical. She also created a series of the stations of the cross (I’ll let you look those up on your own).

Andrews worked as a secretary at the Grosvenor School beginning in 1925 and soon began making linoleum cuts under the school’s leader, Claude Flight. She became close friends with Cyril Power (I promise, I will cover both Flight and Power soon), sharing a studio until 1938, as well as collaborating under the pseudonym Andrew-Power. During World War II, while working as a welder in a factory, she met her husband Walter Morgan. The couple emigrated to Canada and settled on Vancouver Island in 1947. She continued making color linoleum cuts well into the 1970s. I love that Andrews has such a strong point of view. I love the palette and the colors’ vibrancy. I love the high-design sense and reductiveness of the objects. I love the range of subjects. Well, there is not much about her work I don’t love. Please meet Sybil Andrews. Ann Shafer What happens if you live in Melbourne in the early part of the twentieth century in an era of pretty conservative art making? How do you learn about what is going on in Europe and other places that are so far away? There is no television, no internet.

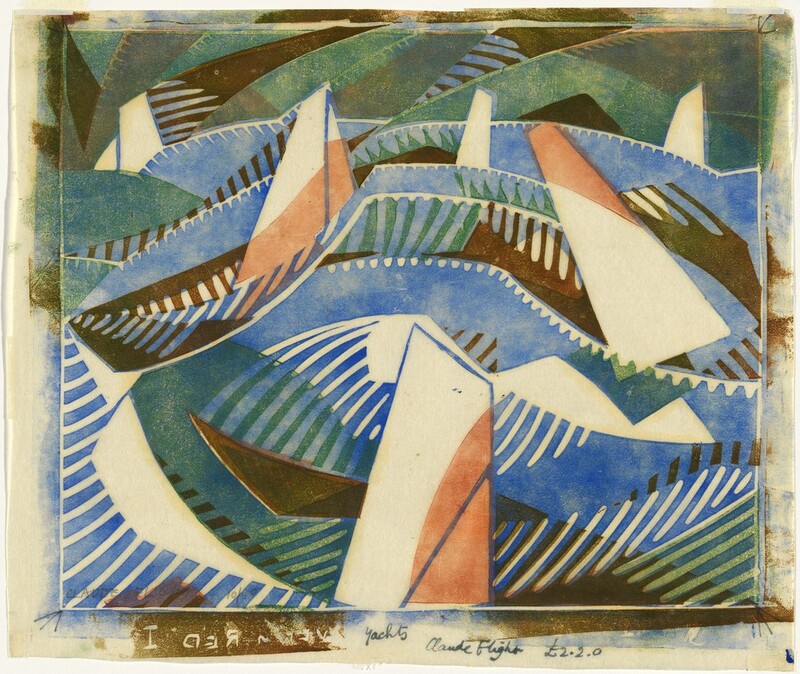

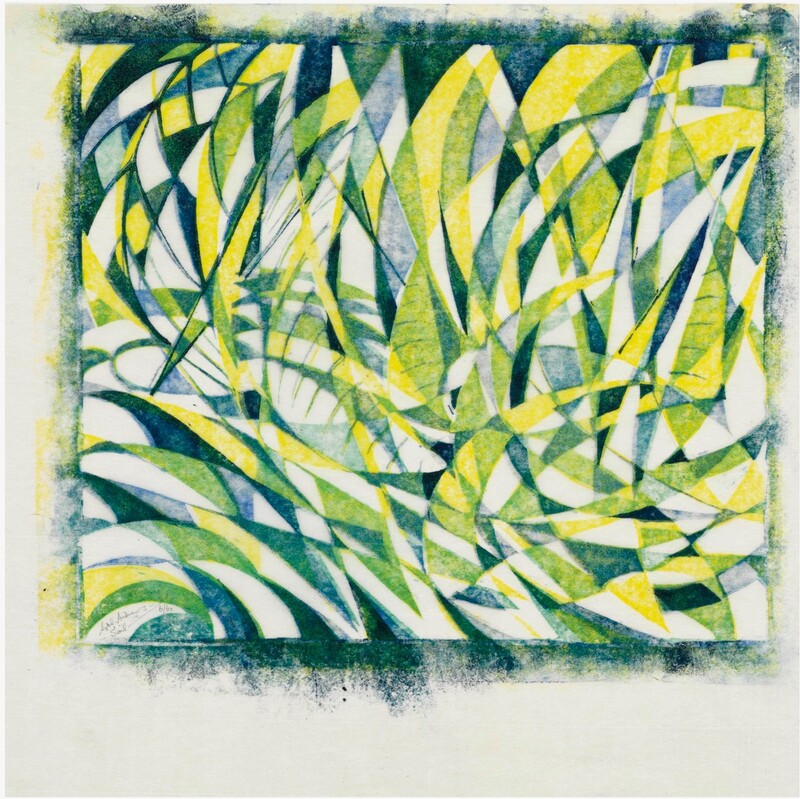

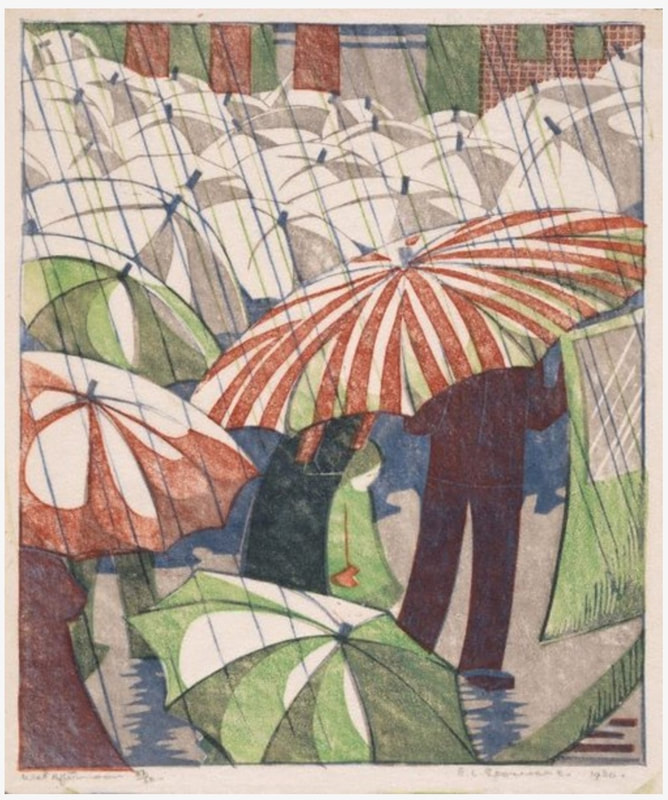

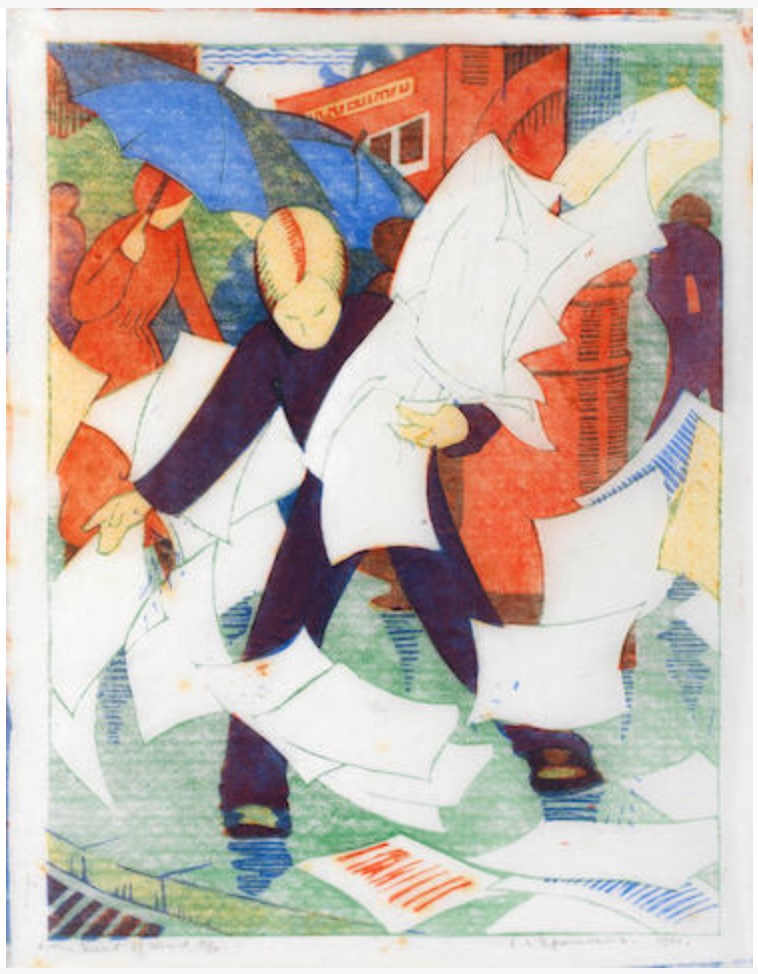

Why, one goes to libraries and book stores to find publications that might expand one’s horizons. One such oasis of cosmopolitan culture in Melbourne was found at the Depot Bookshop run by the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria. It was there in 1928 that a young artist named Eveline Syme came across a small booklet called Lino-Cuts, written by Claude Flight. Claude Flight was the well-known teacher at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in London who was the defacto leader of a group of printmakers named for the school. (We recently met Lill Tschudi and Ursula Fookes who both studied there.) Syme and another young artist, Ethel Spowers, would have seen the school advertised in The Studio, the leading British art-periodical also available at the Depot Bookshop. Both women were so taken by the illustrations in Flight's booklet that they traveled to London and enrolled—Spowers arrived in late 1928, and Syme came a few months later, in 1929. Located in London's Warwick Square, the Grosvenor School was an informal place that offered up random courses. It had a growing reputation due mainly to Flight who was one of its charismatic teachers. He inspired many artists to work in linoleum cuts in multiple colors (one block for each color) and to adopt Flight’s method of using both printing ink and oil paint to achieve particular color effects. Flight promoted the idea of the democratic virtue of linoleum cuts as a cheap commodity in an overpriced art market. (The Grosvenor School closed its doors in 1940.) Syme wrote about Flight and his style: “Sometimes in his classes it is hard to remember that he is teaching, so complete is the camaraderie between him and his students. He treats them as fellow-artists rather than pupils, discusses with them and suggests to them, never dictates or enforces. At the same time he is so full of enthusiasm for his subject, and his ideas are so clear and reasoned that it is impossible for his students not to be influenced by them." Today’s artist, Spowers, studied with Flight from 1928 to 1930, went home for a bit, and returned to London in 1931 for a spell. During her time back home in 1930, she mounted a show, Exhibition of Linocuts, at the Everyman Lending Library in Melbourne that featured her prints as well as those by Syme and fellow Aussie Dorrit Black. In turn, the three women all found an outlet at the Modern Art Center established in Sydney by Black in 1931. Spowers also acted as an informal agent for Flight, promoting his work down under. Spowers, sadly, died of cancer at the young age of 56 in 1947. Meanwhile, in England, influential touring exhibitions, arranged in conjunction with the Redfern Gallery, traveled around promoting the linoleum cuts of the Grosvenor School, and included the work of the Australian women. Linoleum cut prints by the artists of the Grosvenor School were popular until they seemed too colorful and optimistic in the face of the War. They fell off the radar and it wasn’t until the 1970s that there was really any market for them. Now, of course, their prices are sky high. Ann Shafer There are artists associated with the Grosvenor School that are well known (Sybil Andrews, Lill Tschudi, Claude Flight, and Cyril Power), and then there are others who are less well known. Meet Ursula Fookes, about whom very little is available online. She studied with Claude Flight at the Grosvenor School in 1929–31, which is where the color linoleum cut celebrating speed and modern life was a central subject.

Following her studies, not much is known except that she spent the last months of the war on the Continent running a mobile canteen, which was a war-era version of a food truck. (She kept a rather compelling diary of that time, which is preserved at the Imperial War Museum.) After the war she seems to have moved to the country and ceased showing her art (or possibly stopped making any). Details are a bit fuzzy. Hopefully some industrious PhD student will take her on and flush out Fookes' herstory. Fookes’ sensibility is different than that of other artists we’ve looked at (see recent post on Lill Tschudi). It’s a bit less frenetic, perhaps a bit more staid. But I love discovering lesser-known artists within a movement. What makes their work less desirable than others who become the face of said movement? Is it just a matter of exposure? Is it that Fookes didn't create much art after this initial push and fell off the proverbial radar? Did the other artists do something different? Did they have different relationships with galleries, dealers, curators? Curious. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed