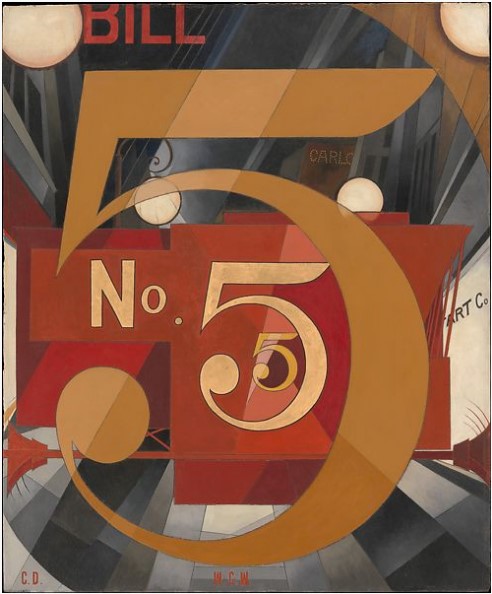

Ann ShaferI wrote my senior thesis on my second and more abiding love, Charles Demuth (DEE-muth, not deMOOTH). I focused on several groups of his watercolors featuring figures: circus and vaudeville acts, literary illustrations for Henry James and the like, and erotic-ish scenes including sailors dancing, lolling on the beach, jazz clubs, and Turkish baths. I don’t think I have my copy of that paper anymore, which is just as well. Not that the watercolors aren’t great, they are, but that my writing about them was surely riddled with holes. Demuth remains a favorite because not only are the figural watercolors awesome, his still lifes in watercolor are breathtaking and his output in painting is stunning. Two of my favorite paintings are I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928, and My Egypt, 1927, which I saw nearly every day when I worked at the Whitney right out of college.

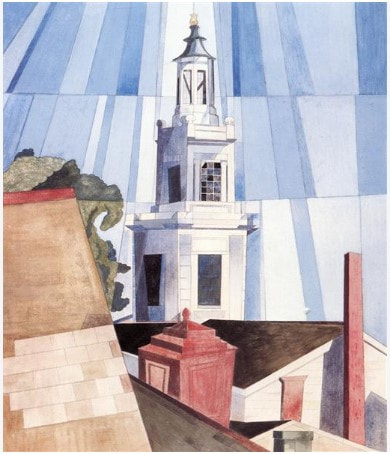

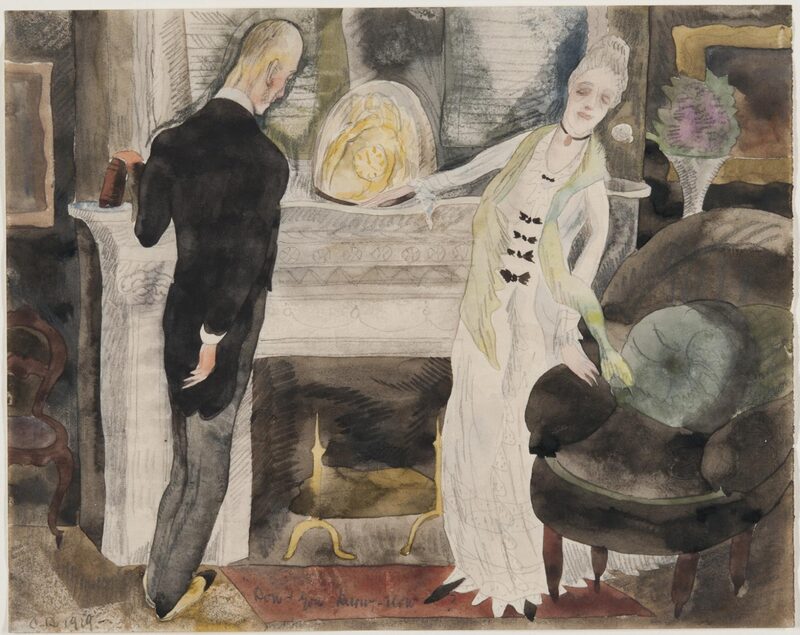

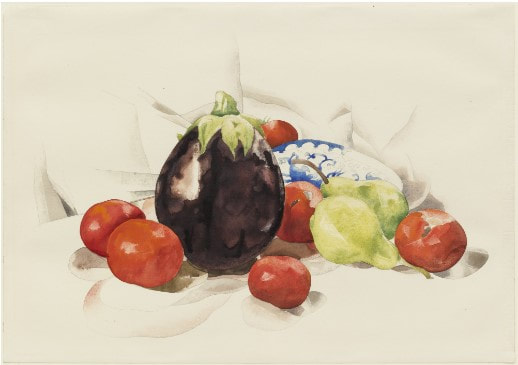

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold is one of Demuth’s eight portraits painted in tribute to various American writers, artists, and performers. None are physical likenesses, but rather they show imagery that evokes the person and their work. This one is a tribute to William Carlos Williams who was a friend, poet, and his physician. (Demuth died at age 51 due to complications from diabetes. He was one of the earliest patients to give himself insulin shots—a brand new treatment.) The title of Demuth’s painting is taken from Williams’ poem that describes the sights and sounds of a firetruck speeding down a New York City Avenue: Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city It always makes me smile when I happen upon I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was more fortunate to be able to look at My Egypt every day for two plus years at the Whitney Museum of American Art (back when it was in the Breuer building at Madison and 75th Street). Its title gives a pretty substantial hint as to what it’s about: our grain elevators, water towers, and factories stand as monuments to America’s achievements in industry in much the same way the pyramids glorify the pharaohs in ancient Egypt. One could also guess that Demuth is likening the dehumanizing of the labor force in big industry of the 1920s to the slaves that built the pyramids. In addition to factories and grain elevators, Demuth painted church spires, which often loom up over the viewer. Sometimes it appears that an artist’s imagination has run away with them, that the scene portrayed couldn’t possibly exist in real life, and I frequently wonder how they conceived of such a view. For instance, Thomas Moran’s paintings of Yellowstone National Park look like confections in yellow and pink, but parts of the park really are those same colors. Demuth’s point of view became very clear to me on a visit to the Demuth Museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The museum includes the family home and the tobacco shop next door, which are in the middle of downtown. I made a pilgrimage there one January only to discover the museum is shuttered in the winter (should have checked the internet). Disappointed but not daunted, I knew there was a garden behind the building where Demuth had spent much of his young life painting the flowers his mother grew due to his frailty (severe diabetes). I made my way down the tiny passthrough between the buildings and emerged into a lovely, small, brick-lined garden. Then I looked up and my jaw dropped. Looming over the garden courtyard is the giant church steeple of Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, which is directly behind the house. It was as if one of his paintings, like The Tower, 1920, came to life, after which his style and acute angles made so much sense. That was one of only three times that my jaw has dropped for art: the first was in a nineteenth-century art class in college when a slide (yes, slide) of a Manet painting of lilacs in a glass vase popped up, the second was while standing in front of Velasquez’s Las Meninas at the Prado. While Demuth’s paintings are amazing, I have, no surprise, a soft spot for his watercolors. The still lifes are worth checking out. He has such a delicate and deft touch, he’s unafraid of leaving white space, and I love his use of salt and small squares of blotter paper to gain that mottled texture and those sharp edges. I could look at the fruit and flower watercolors all day long. The figural watercolors are less easy to love, but they are an interesting facet of his work. The illustrations for various works of literature—he seemed particularly keen on Henry James—weren’t commissioned to illustrate published works, rather, they were personal, just for him. The circus performers and vaudeville acts are quirky and fun. And his scenes of sailors partially nude on the beach or in dance halls, where two men dancing with women gaze longingly at each other, or a self-portrait at the Lafayette bathhouse reveal he was an openly gay man partaking in the burgeoning underground gay subculture in post-World War I New York. These erotic works were not for public consumption, but in subsequent years they have offered inspiration to artists working with similar themes. Only Hayter has eclipsed my deep and abiding love for Demuth. No, actually, I find Demuth’s work more beautiful and personally satisfying. There is just so much more to discover with Hayter. Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928 Oil, graphite, ink, gold leaf on paperboard (Upson board) 35 1/2 x 30 in. (90.2 x 76.2 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949, 49.59.1 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) My Egypt, 1927 Oil, fabricated chalk, and graphite on composition board 35 15/16 x 30 in. (91.3 x 76.2 cm.) Whitney Museum of American Art: Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 31.172 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) The Tower, 1920 Tempera on pasteboard 23 1/4 x 19 1/2 in. (591 x 495 cm.) The Columbus Museum of Art: Gift of Ferdinand Howald, 1931.146 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) The Revelation Comes to May Bartram in Her Dressing Room, 1919 Illustration for the short story "The Beast in the Jungle," by Henry James Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 203 x 257 mm. (8 x 10 1/8 in.) Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Frank and Alice Osborn, 1966, 1966-68-6 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) Eggplant and Tomatoes, 1926 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 358 x 509 mm. (14 1/8 x 20 in.) Museum of Modern Art: The Philip L. Goodwin Collection, 99.1958 Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935) Dancing Sailors, 1918 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 204 x 257 mm. (8 1/16 x 10 1/8 in.) Cleveland Museum of Art: Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1980.9

1 Comment

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed