Ann ShaferIs the Enlightenment really the Endarkenment? It’s one thing to strive to understand and organize all human knowledge, and it is another thing to use that knowledge to justify the enslavement of a people and the subjugation of women. Stay with me here.

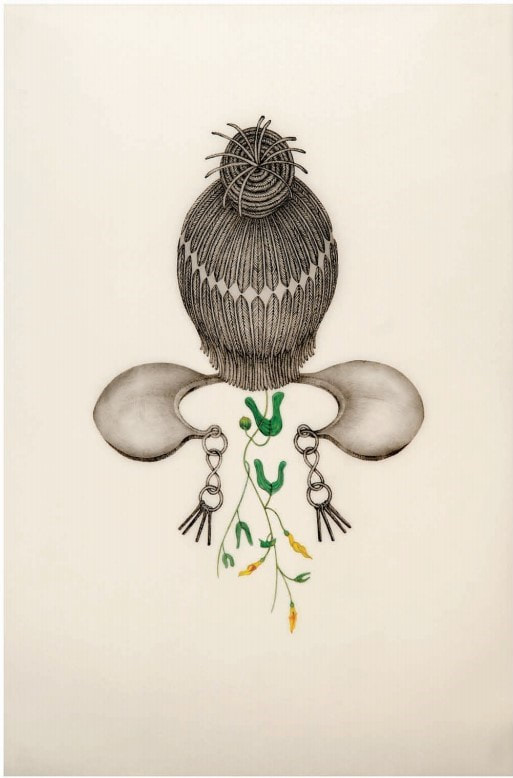

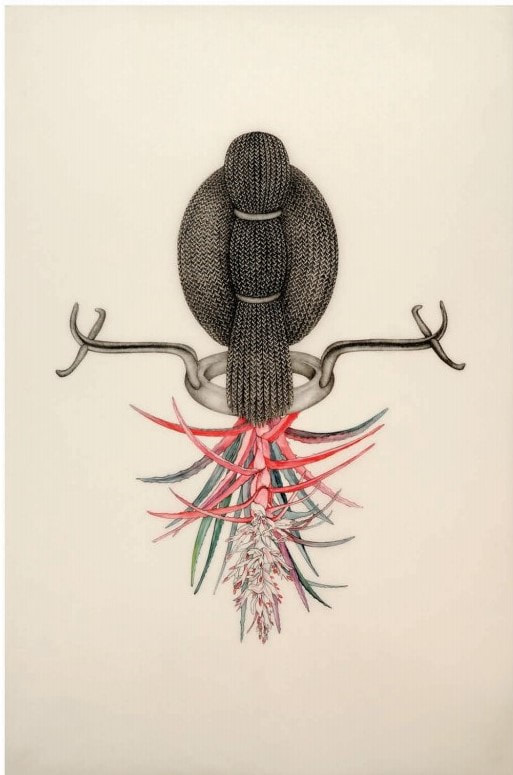

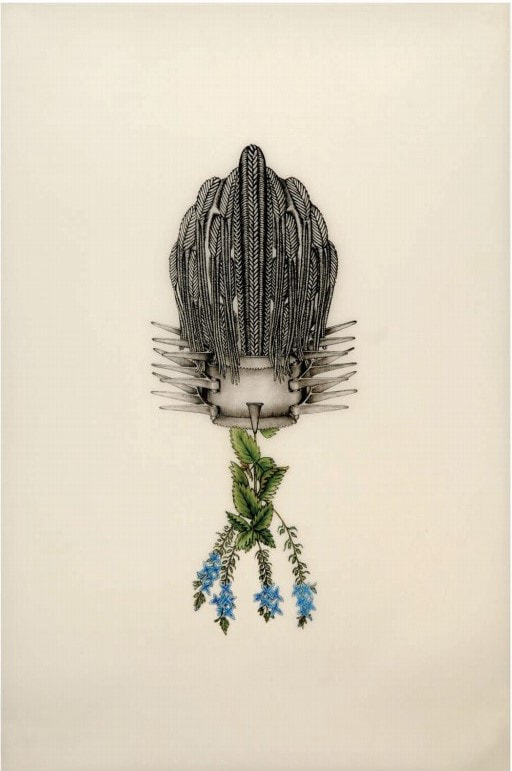

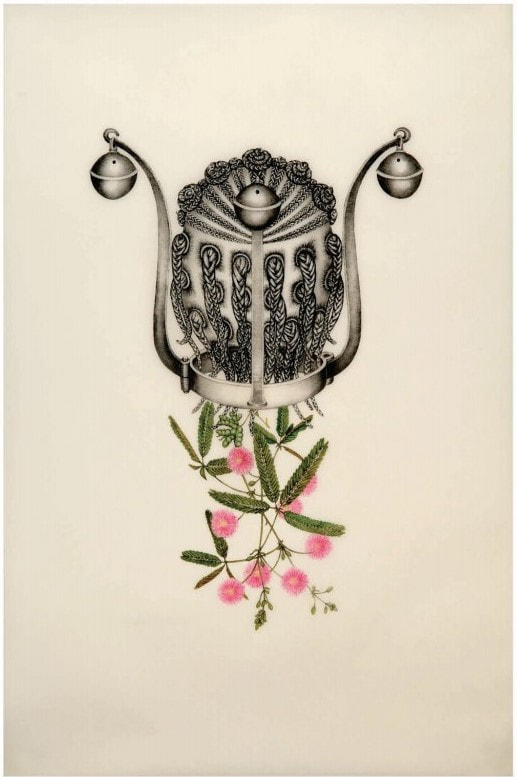

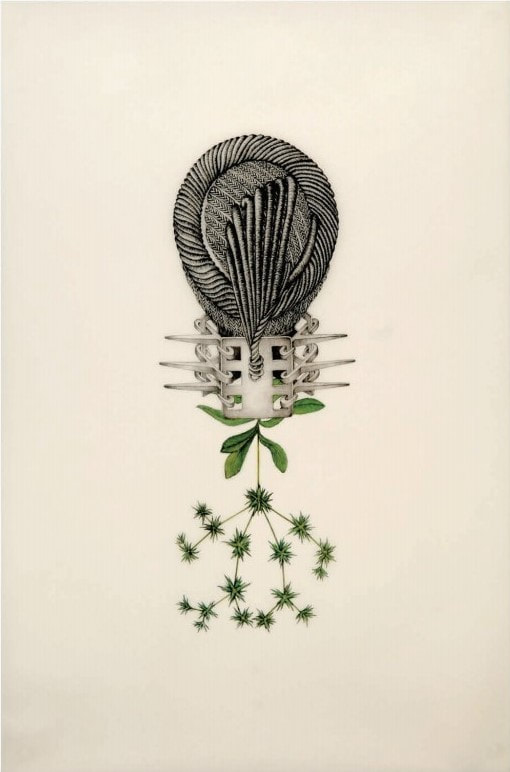

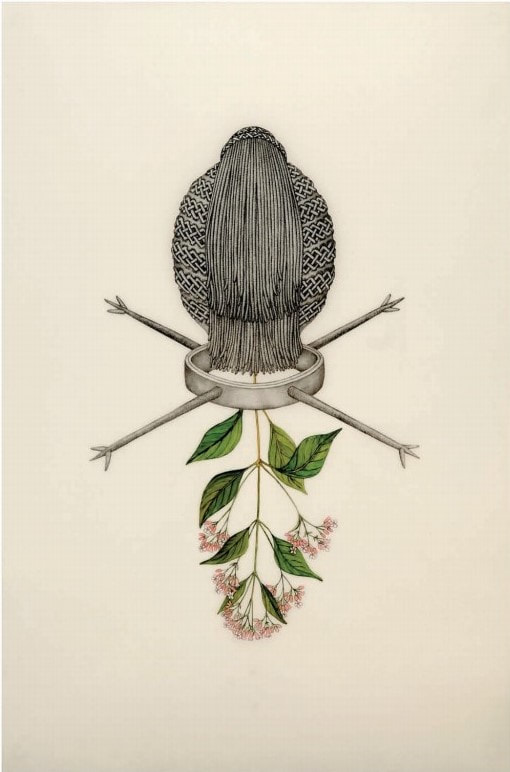

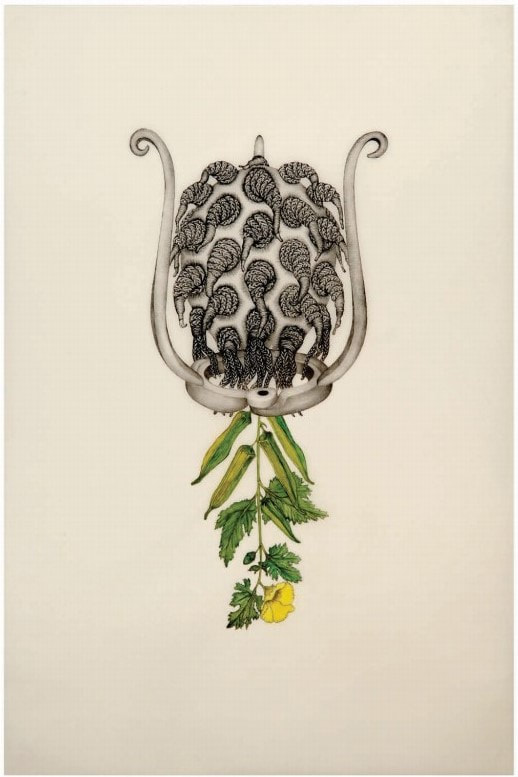

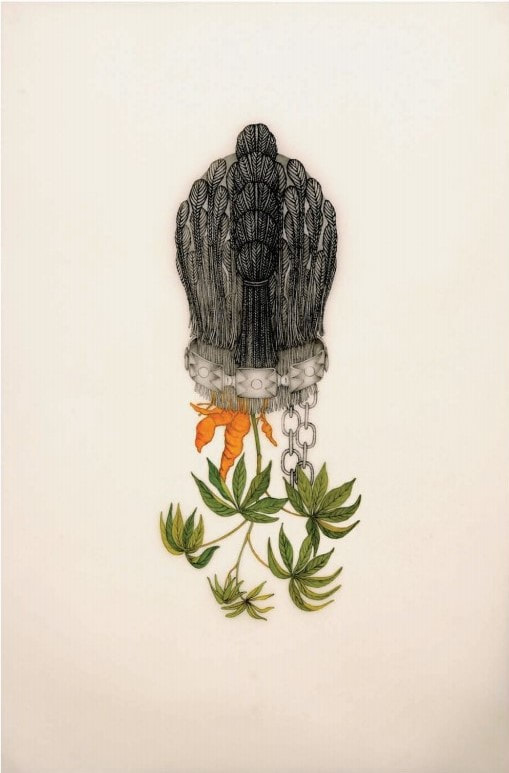

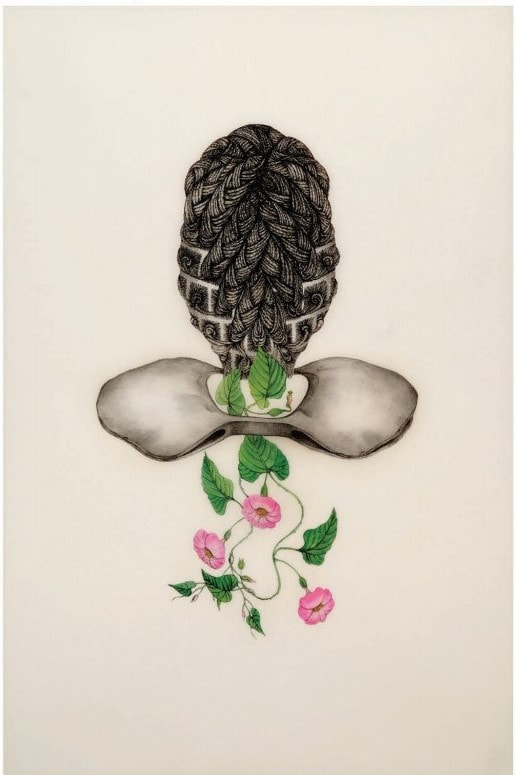

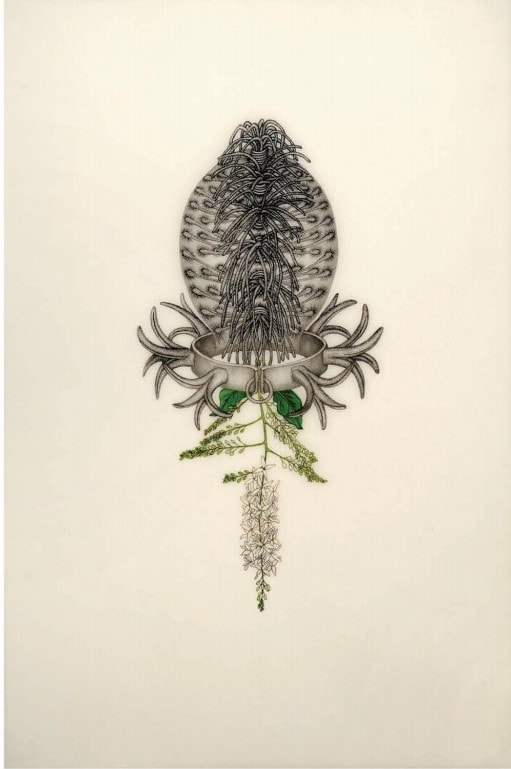

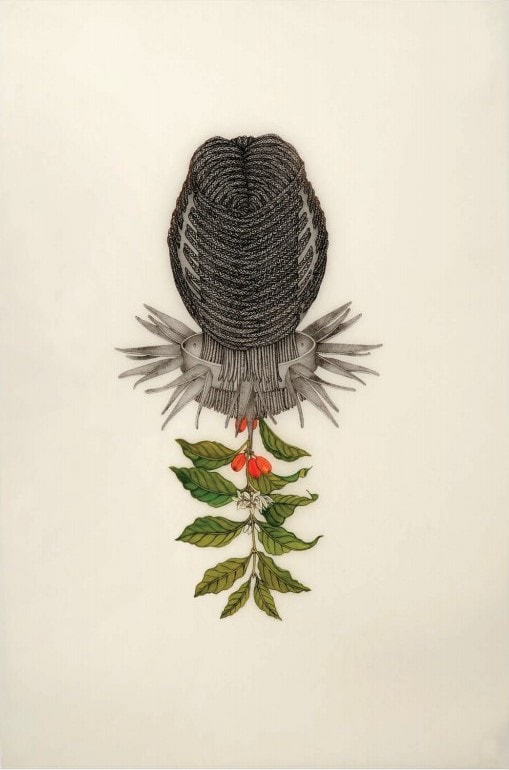

On a recent, long drive, we started listening to Isabel Wilkerson’s new book, Caste. The recording is fourteen hours long, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. In fact, we’re still in the eight-pillars-of-the-caste-system part that sets up the whole thing. It’s dense, intense, and important. One of the pillars was an ah-ha for me. It has to do with heredity, the idea that one’s caste is inherited through family. In most cultures, this placement into a certain level of society follows the patriarchal line. In America, however, from its earliest days, caste was passed down through the matriarchal line. This turnabout was necessary because it enabled the upper caste (white men/slave owners) to rape enslaved women in order to produce yet more slaves that could add to the labor force or be sold for a profit. Rape as a profit center. It makes me sick. Maybe I’m naïve for being surprised, but that one really got to me. WTAF?!? After the trip, a friend/colleague mentioned the artist Joscelyn Gardner's portfolio, Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers…, 2009–11, and I knew it would make a powerful post. It also felt like no coincidence that she told me about the works at the same time I’m deep in Wilkerson’s book. I have never resisted talking about and introducing you to works that pack a political punch. Hold on to your hats, here we go. First, know that Gardner’s portfolio intertwines information gleaned from the papers of an English slaveholder and amateur botanist named Thomas Thistlewood who settled in Jamaica in 1750. His papers are well known and are one of the fullest and most extensive accountings of that period, including everyday matters having to do with the slave business, the weather, horticulture and botany, crops, and financial issues (they are held by Yale’s Beinecke Library). In addition, the papers include a meticulous accounting of his violent sexual transactions. Scholar Alison Donnell (in an exhibition catalogue featuring Gardner’s work from 2012) uses the term transaction because Thistlewood recorded in excruciating detail some 3,852 acts of intercourse with 138 women. He was no sex addict. Donnell goes on to pose these pertinent questions: “How do we represent the violence and violation of slavery without repeating its spectacular effect? How do we speak about subjects lost to history and yet not entirely unknown? How can we make visible the systems of representation that support an unequal distribution of authority, knowledge, and power?” Enter the artist Joscelyn Gardner. She grew up in Barbados where her family dates back to the seventeenth century—one can only assume they were land- and slaveowners—and now calls London, Ontario, home. In her portfolio of twelve lithographs printed on frosted Mylar (lending a particular luminescence), each portrait includes the head of an African woman seen from behind showcasing an elaborately braided hairstyle, a complicated torture device, and a delicate botanical specimen. The delicacy and intricacy of the rendering draws viewers in; it is an oft-used trope that usually works. In traditional portraiture, the subject faces the viewer, often confronting them. Portraits were created to showcase the sitter’s stature, knowledge, and wealth. Yes, these would be mostly men. Women were often portrayed as allegorical figures (nude, naturally), or in relation to the men in their lives. Gardner’s subjects have their backs turned to us, preventing us from knowing who they are individually. This does several things. It not only subverts the male gaze and objectification, but also allows the artist to portray women whose identities are lost to history. For me, they become symbols of the strength and determination of enslaved women without the spectacle of their circumstances. This seems especially appropriate in this instance because the artist herself is white. (This is a much larger debate that requires its own post.) In Gardner’s hands, the hair is the manner of capturing character as she bears witness to lives lived. The elaborate hairstyles of meticulous braiding mark each as an individual, but also reflect the sisterhood required to accomplish them. These hairstyles are based on contemporary examples tying the past to the present and acknowledging hair’s position as a signifier of personhood, status, and position, as well as being a key means of individual expression. But remember, hair is also a fundamental means of differentiating race and class. During slavery, the worn instruments of torture were visible manifestations of control and systematic enforcement of authority. Interestingly, depictions of bucolic plantation life appear in contemporaneous artworks, but few examples exist showing the habitual violence necessary for keeping the system operational. More truthful imagery begins to surface with the Abolitionist movement at the end of the eighteenth century, but the subjects are faceless—a continued effort to dehumanize slaves. This is surprising when one considers the power of postcards of lynchings produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that were widely shared and had the effect of reinforcing that terror. Perhaps the pastoral images of exotic plantations for a European audience naturalized the injustices that were codified into laws making men and women the property of others. By subverting accepted narratives of the era, Gardner recognizes slave women, gives them a voice and a presence. Representation matters. As the world became fascinated with classification of things, the definitions of words, the knowledge of how things worked, of Enlightenment, was this all code for “we have to justify the subjugation of ‘other’ human beings in order to build a new world?” The botanical specimens Gardner adds to each portrait echo the style of eighteenth-century books cataloging plants with exquisitely delicate illustrations. Gardner includes their Latin names—a colonizing effect wholly tied to European conventions of the study of natural history, which was a booming industry in the print trade in the eighteenth century. The names set in parentheses are not the common names of the plants but the names of slaves from Thistlewood’s diaries, reflecting another colonizing act in which the assignment of names was arbitrary and separated slaves from their African identities—more subjugation and dehumanization. But the applied knowledge of plants has long been the domain of women, and whose use has long been distrusted by men. Remember healers were thought to be witches in the early years of the Republic? In Gardener’s prints, these particular plants are in fact Abortifacients, which were used to abort unwanted pregnancies. Gardner’s portraits allow these women to control the male gaze upon them, display individualism through hairstyles, acknowledge but transform the objects of torture, and twist Thistlewood’s intense interest in botany to identify plants used to counter his attempts to impregnate and profit from the births of black bodies carried by women with few options. Notes: The portfolio was printed at Open Studio, Toronto, with master lithographer Jill Graham. See the thorough and thoughtful catalogue on Gardner’s work that includes essays by Jennifer Law, Alison Donnell, and Janice Cheddie here: https://fcd17b62-2ec4-4ce5-8701-cf90a26cd17a.filesusr.com/…. Joscelyn Gardner (Barbadian and Canadian, born 1961) Printed by Jill Graham, Open Studio, Toronto Aristolochia bilobala (Nimine), 2010 Bromeliad penguin (Abba), 2011 Trichilia trifoliate (Quamina), 2011 Veronica frutescens (Mazerine), 2009 Mimosa pudica (Yabba), 2009 Eryngium foetidum (Prue), 2009 Cinchona pubescens (Nago Hanah), 2011 Hibiscus esculentus (Sibyl), 2009 Manihot flabellifolia (Old Catalina), 2011 Convovulus jalapa (Yara), 2010 Petiveria aliacea (Mirtilla), 2011 Coffee arabica (Clarissa), 2011 From the portfolio Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers… Portfolio of twelve lithographs with hand coloring on frosted Mylar Each sheet: 915 x 610 mm (36 x 24 in.)

0 Comments

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed