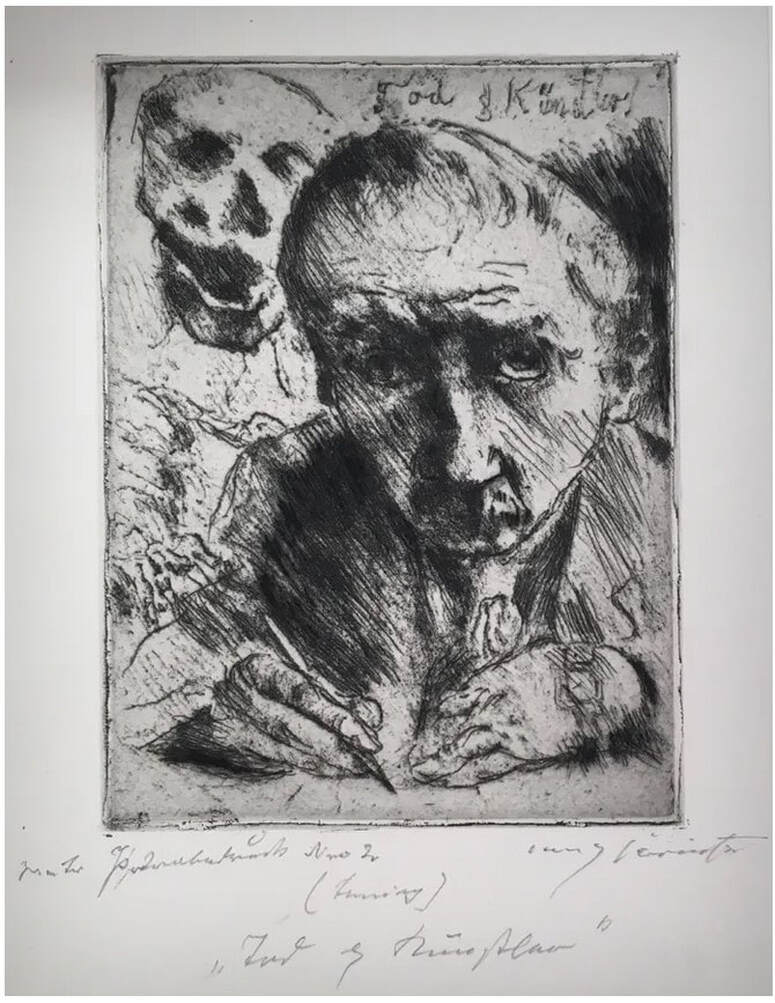

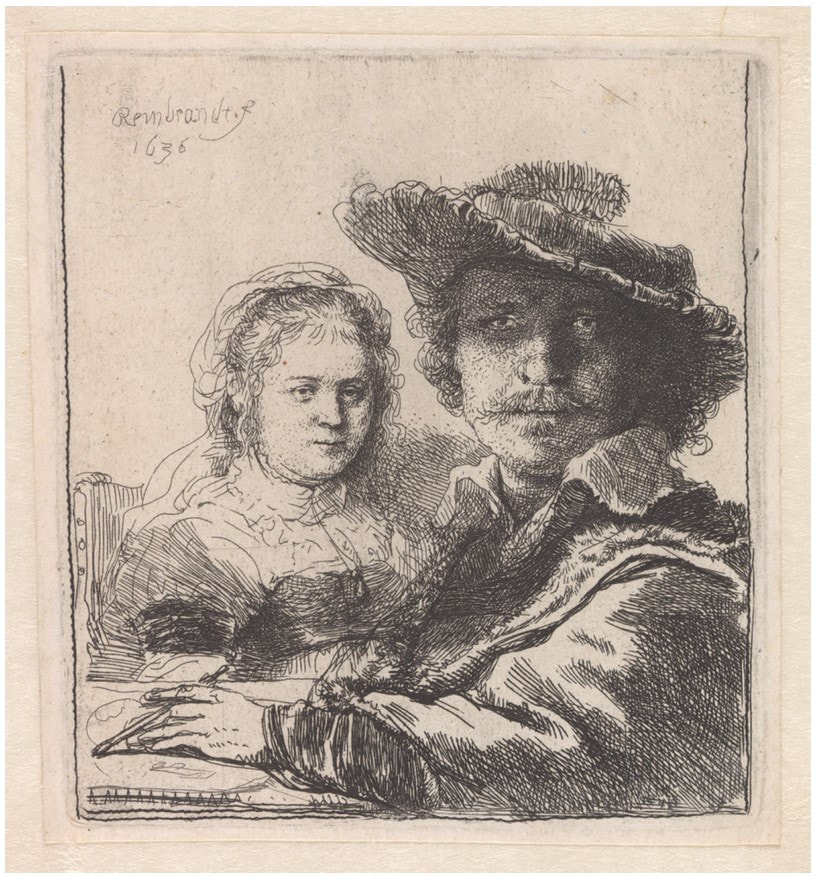

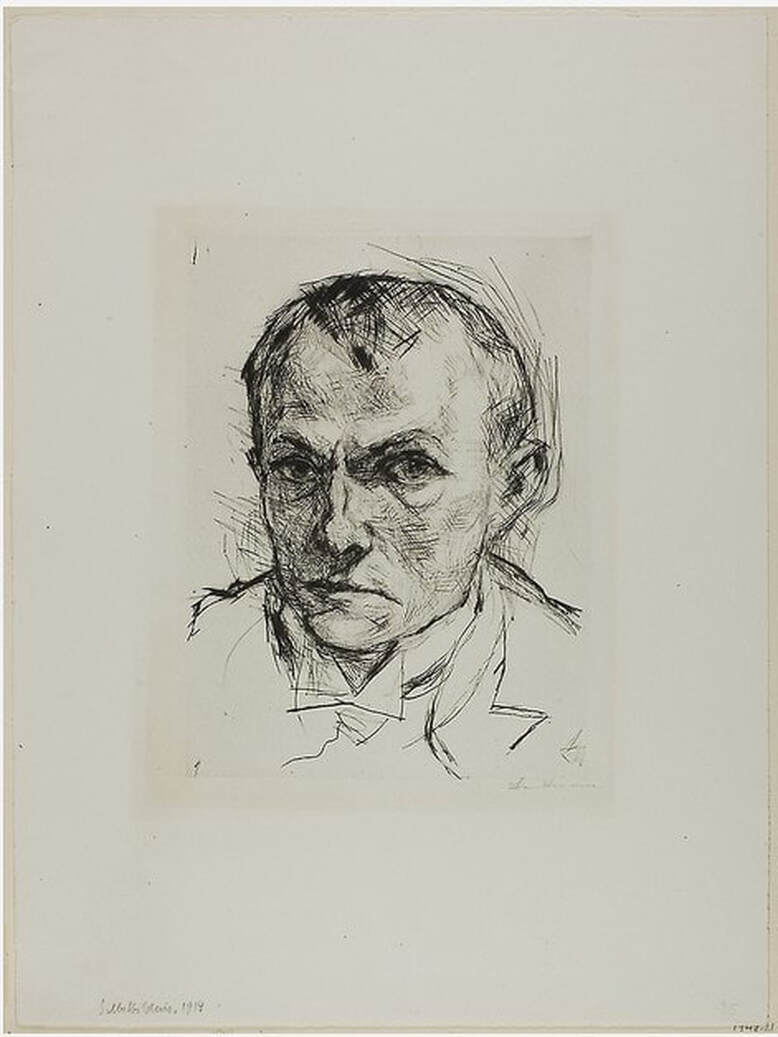

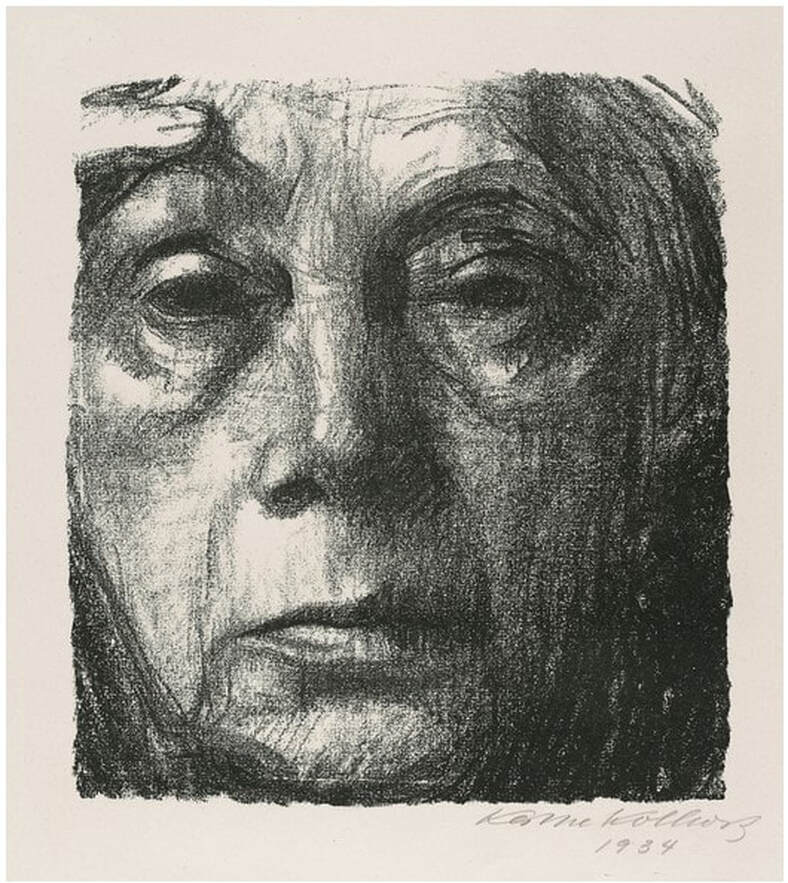

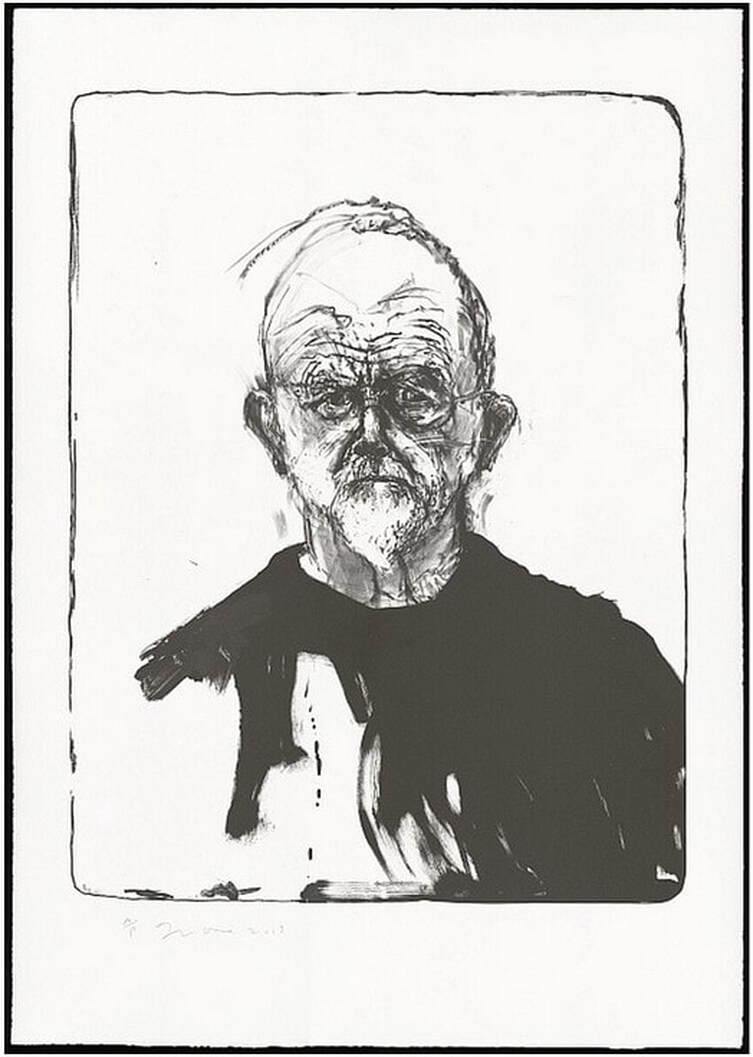

Ann Shafer When I started working for Full Circle, I was curious to see what kinds of art was in its stable, and what I could do to bring any of it to light for you. One painting, which is hanging in Catalyst Contemporary’s “backroom” among other represented artists’ works, I just love. It’s by Damon Arhos and it’s a self-portrait. I’ve always been fascinated by self-portraits and why they are rife throughout art. Let’s look back for a minute before we get to Arhos’ painting. In Western art the first self-portrait is believed to be by Jan van Eyck in 1466. Why then; why him? Likely it has to do with the development of clear, useful mirrors. Until then, there was no way to see ourselves with any accuracy. Those first mirrors must have surprised and delighted. Consider, too, that historically there had been little distinction between individual artists and artisan-craftsmen of guilds, so no cause for taking one’s own likeness. Individualism was not a thing yet. When and who decided that an artist’s work was the product of immense and unusual talent worthy of a signature and individual notice? I’m sure there are other examples, but my printmaking mind goes directly to our old friend Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) since he was a master of self-promotion and marketing. He drew his first self-portrait at age 13—but it is a drawing and its circulation was limited. Hell, he wasn’t even a professional artist at that age. But I’ve always been impressed that by 1500 (age 28) he had the kahunas to portray himself in the guise of Jesus Christ. I mean, honestly. Self-portraits were a way of promoting one’s talent, a calling card if you will. Plus, the model was accessible and cheap. But more than that, they are a means of introspection. Self-portraiture enables artists to look inside, figure out who and what they are, how they want to be seen. Many artists have made them, but how many have really dug in and investigated their own selves in a serial manner? Obviously for me, printmakers come to mind: Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Jim Dine. It’s fascinating to think about what drives us to picture ourselves and to what end. I’d suggest artists use self-portraiture to reflect on what it means to be human, creative, alive. These days, are self-portraits still relevant, especially in this era of selfies, or do they seem old fashioned? What if the self-portrait was only one element in a work that explores more than the physical features of a face? The painting hanging in the backroom at Catalyst Contemporary, which I mentioned at the top of this post, is by Damon Arhos who unfolds queer culture and seeks to promote love and acceptance while investigating social and political issues of gender and sexuality across media. He uses pop culture references fused with the personal to make his work approachable to viewers, and also to be true to himself. In Agnes Moorehead & Me (No. 1/Figure Portrait), 2019, Arhos digitally combined his own face with that of actor Agnes Moorehead as the basis for the painting. The two are merged in a stylistic way with an acidy palette—I love that mustard color. It's one of a series of Moorehead paintings. But why Moorehead? She was an accomplished actor who is now best known as Endora, the mother of the main character in the 1960s television series Bewitched. Endora and her brother Uncle Arthur, played with zeal by gay actor Paul Lynde, became lightning rods for the gay community in subsequent decades due to the characters themselves, but also because of assumptions made about the actors’ personal lives. For Arhos, who would have watched Bewitched in reruns, Uncle Arthur was the first positive, if coded, gay character to come across the television screen. And Endora was full-on glamour and fabulousness. What better character to use to explore one’s identity and challenge gender normativity? In Arhos’ hands, the merged image of two faces is reductive and colorful, playful and serious, objective and subjective. He’s used the idea of a self-portrait but turned it into something that is not recognizable as such. Rather, it becomes a symbol for absorbing different identities into oneself in order to expand the possibility of a more open concept of self, one without boundaries or constraints, norms or rules. It speaks of openness, love, inclusion, everyone’s uniqueness, as well as wishes and hopes for a day when one can be whoever one wants to be. In other words, it’s a masterwork. Damon Arhos (American, born 1967) Agnes Moorehead & Me (No. 1/Figure Portrait), 2019 Acrylic on hardboard panel 40 × 30 × 2 in (101.6 × 76.2 × 5.1 cm) Catalyst Contemporary, Baltimore Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, c. 1390–1441) Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), 1433 Oil on oak 26 x 19 cm (10 ¼ x 7 ½ in) National Gallery, London Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528) Self-Portrait, 1484 Silverpoint 27.5 x 19.6 cm (10 5/8 x 7 5/8 in) Albertina, Vienna Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528) Self-Portrait, 1500 Oil on panel 67.1 cm × 48.9 cm (26.4 in × 19.3 in) Alte Pinakothek, Munich Rembrandt van Rijn (Netherlandish, 1606–1669) Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636 Etching Plate: 10.5 x 9.4 cm (4 1/8 x 3 11/16 in) Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950) Self-Portrait, 1914 Drypoint Plate: 239 × 179 mm (9 3/8 x 7 1/16 in) Art Institute of Chicago: H. Simons Fund, 1948.21 Lovis Corinth (German, 1858–1925) Death and the Artist (Tod und Künstler), from the series Dance of Death (Totentanz) 1921, published 1922 Etching, soft-ground etching, and drypoint Plate: 23.9 x 17.9 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/16 in) Block Museum, Northwestern University, Evanston: Gift of James and Pamela Elesh, 1999.21.13 Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945) Self-Portrait, 1934 Crayon lithograph Image: 20.5 x 18.5 cm (8 1/16 x 7 3/8 in) National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Jim Dine (American, born 1935) Berlin 1, 2013 Lithograph 140.4 x 99.2 cm (55 ¼ x 39 in) Albertina, Vienna: Gift of the Artist and Diana Michener, DG2015/68  Lovis Corinth (German, 1858–1925). Death and the Artist (Tod und Künstler), from the series Dance of Death (Totentanz) 1921, published 1922. Etching, soft-ground etching, and drypoint. Plate: 23.9 x 17.9 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/16 in). Block Museum, Northwestern University, Evanston: Gift of James and Pamela Elesh, 1999.21.13.

0 Comments

Ann ShaferOne of my first acquisitions for the BMA was this Jim Dine print. I was working on a small show of his works from the collection and was able to purchase two of Jim's more recent prints to round out the show. The inimitable Tru Ludwig and I set off to NYC to shop at Pace Prints. I knew for sure I wanted to acquire A Side View in Florida, a massive skull derived from Grey's Anatomy, but was open about a second print. Then Raven on Lebanese Border was unveiled, and we knew instantly this was the obvious choice. It has been on view in multiple exhibitions and was my go-to in the classroom because of its Baltimore-related subject matter, experimental printing methods, and multiple techniques. It is probably the work that I got the most use out of. Jim Dine (American, born 1935) Published by Pace Editions, Inc., New York; printed by Julia D'Amario Raven on Lebanese Border, 2000 Sheet: 781 × 864 mm. (30 3/4 × 34 in.) Plate: 676 × 768 mm. (26 5/8 × 30 1/4 in.) Soft ground etching and woodcut with white paint (hand coloring) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, BMA 2007.224 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed