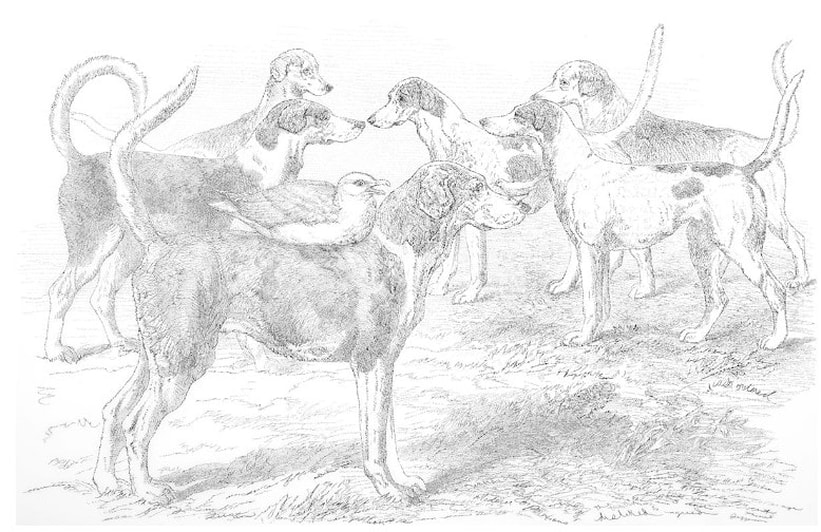

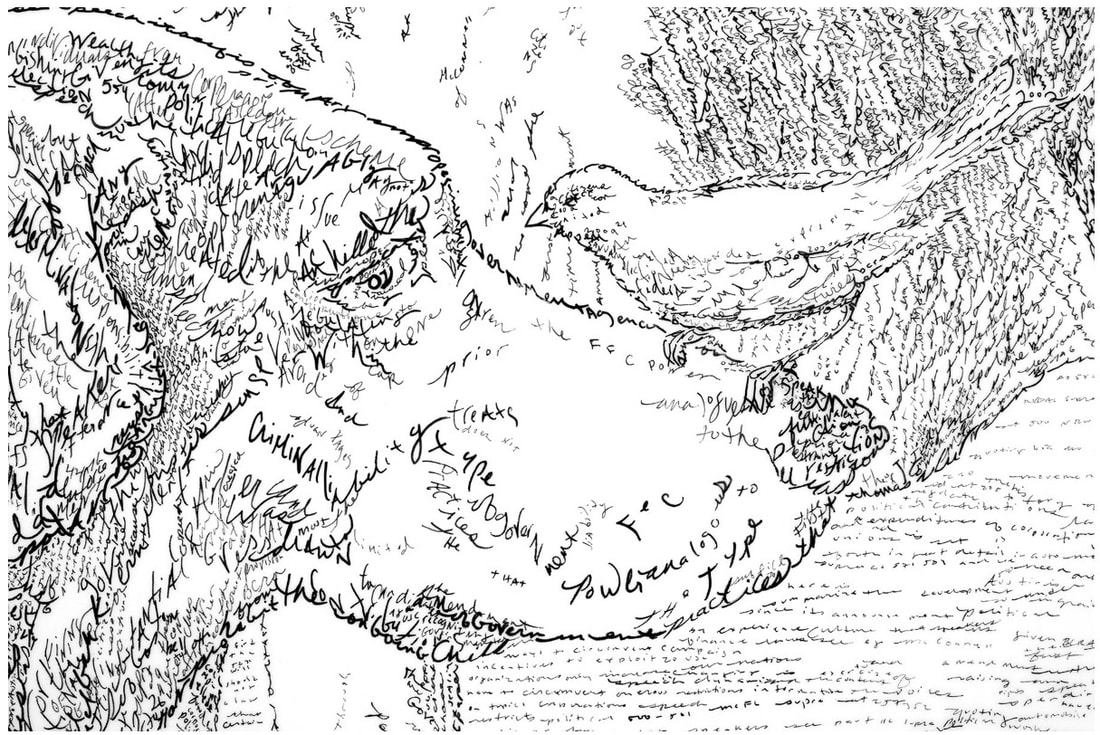

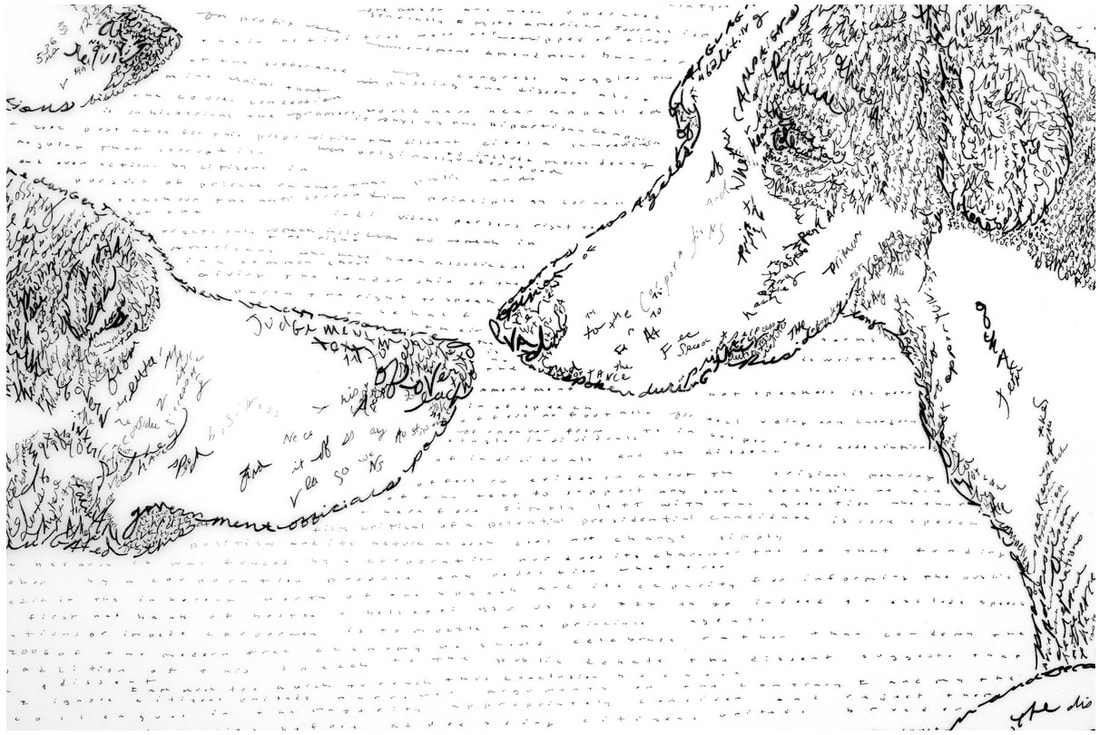

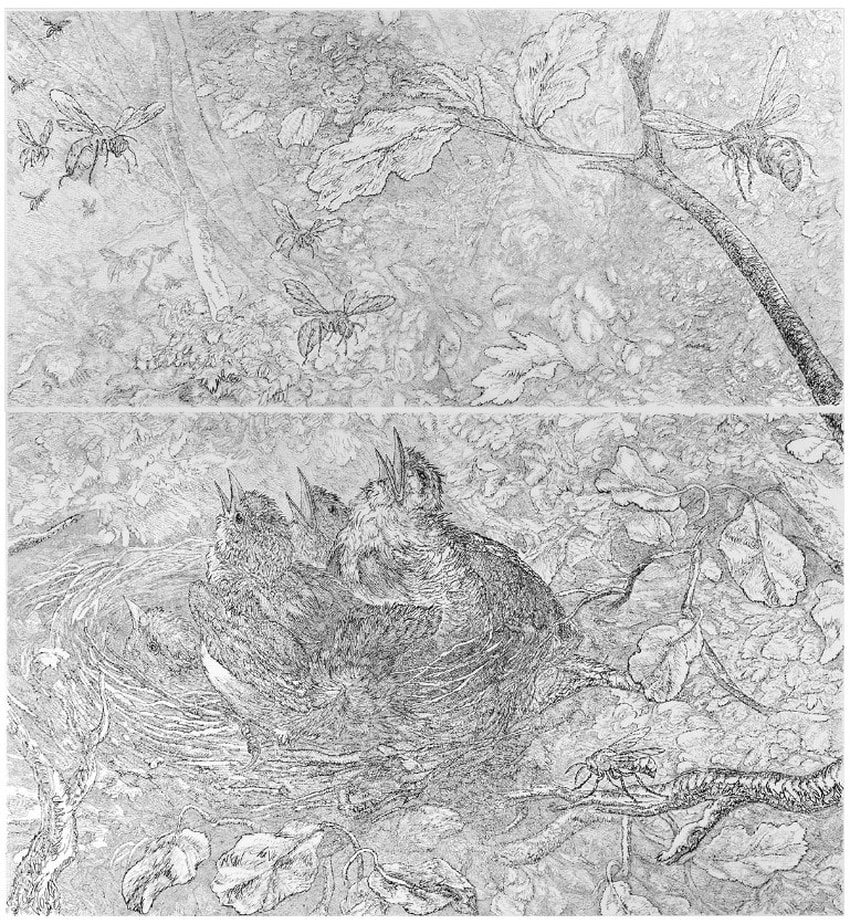

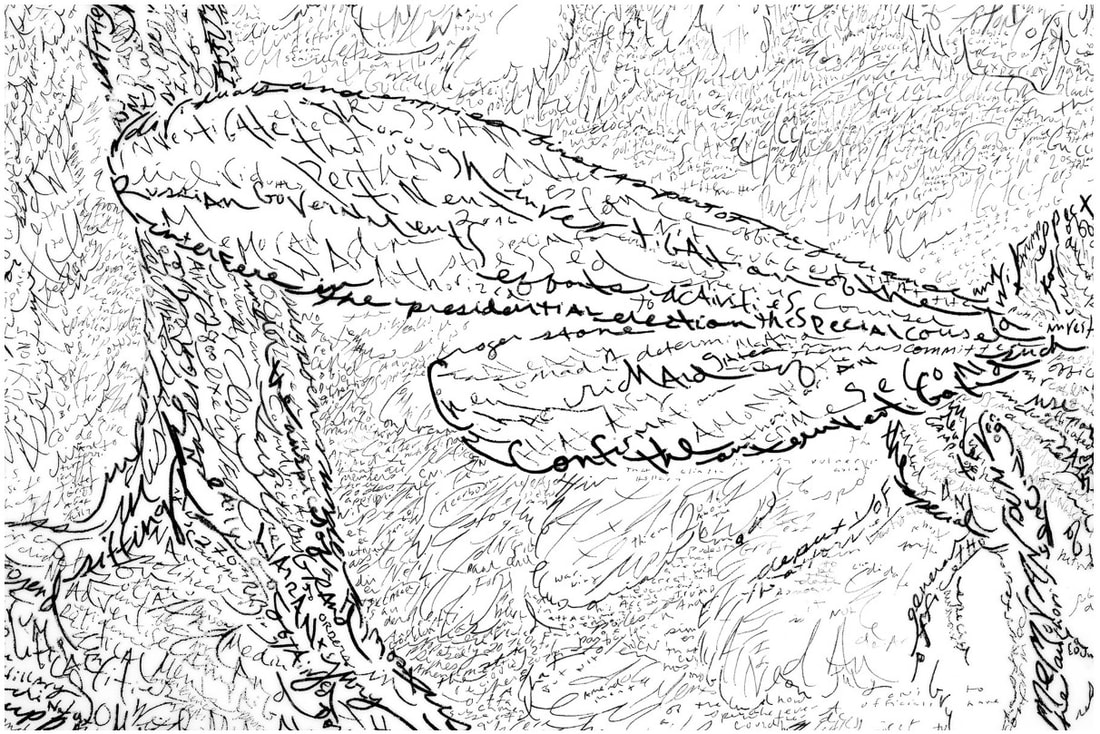

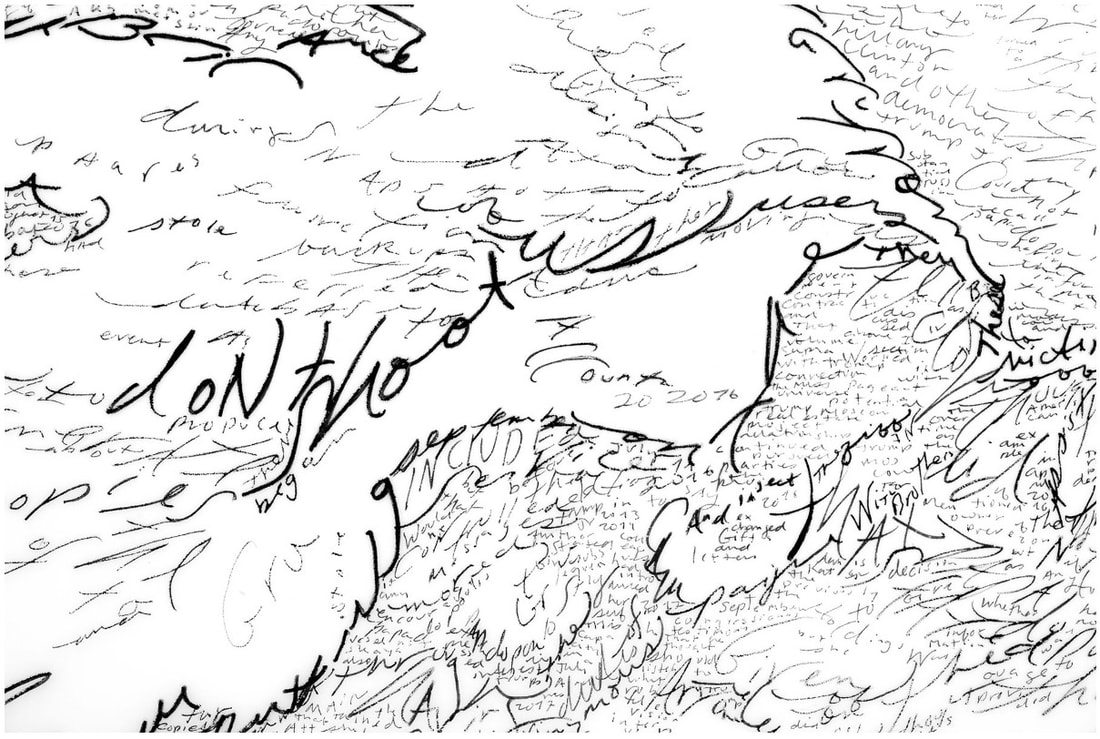

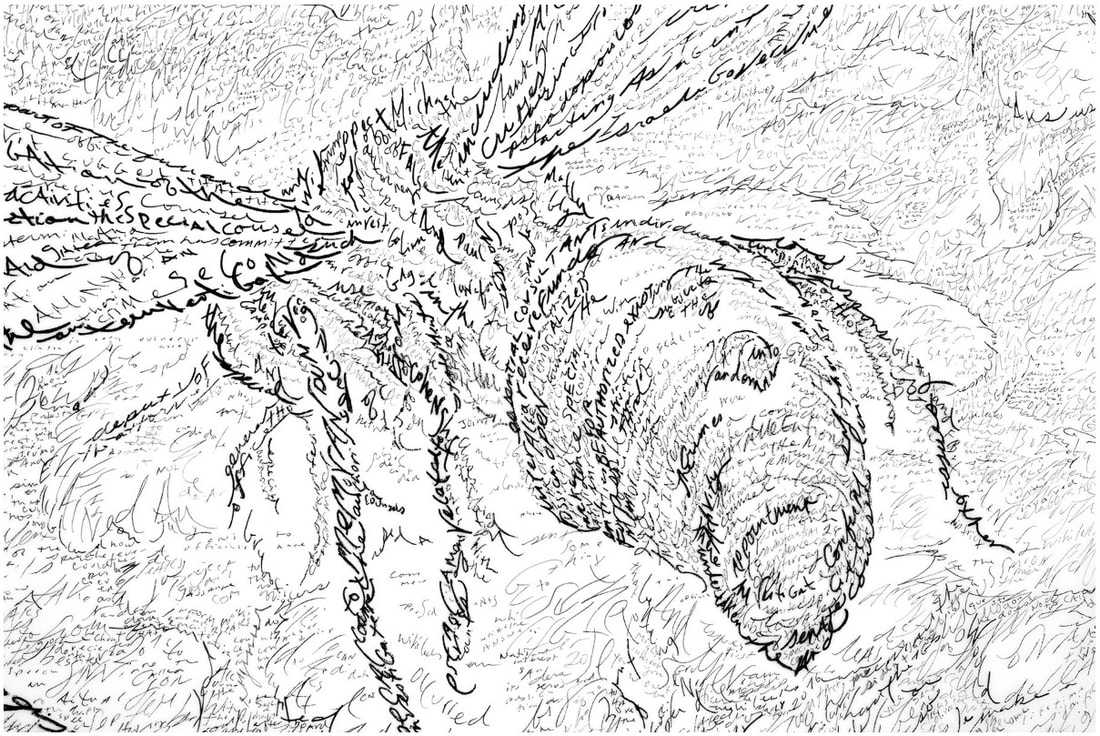

Ann ShaferFor the very first time since I left the museum three years ago (today is the anniversary), I am glad I’m not there anymore. The museum sector is going through some real come-to-Jesus moments. I am having a hard time watching from the sidelines and I can only imagine how frustrated I would be as a museum employee with little to no power to address the issues. Museums, by definition, are collections of things. Categorizing and defining objects and identifying the cultures from whence they came, as well as the notion of them as specimens for our study, has me feeling queasy. The whole enterprise has been rightly identified as a colonializing one. This idea isn’t new—I certainly didn’t come up with it—but at this moment, all these factors are colliding, and I am not sure I see a way for museums to come through it. What do you do when they are entirely based on the idea of studying the “other.” Is it possible to change courses to what necessarily has to be a wholly different model? Just what is the blueprint for this shift? I loved working in museums. I did it for nearly thirty years. I’m an object person. I believe art can help us think through difficult concepts as well as give us pleasure. I never wanted to do anything else besides create ways to tell interesting stories through great art. I love works that sit at the intersection of new and old, of abstract representation and representational abstraction, of beauty and toughness. Filed in the ones-that-got-away column is the work of Mike Waugh whose large-scale drawings demand attention. On the surface one sees an image that harkens back to traditional tropes of Americana: eagles, ducks, hounds, horses. One could write them off as illustrative and backward facing; but stay with it. Zoom in and notice each drawn line is really text. (This technique has a name: micrography.) These lines are not just random words selected because their shapes fit the bill, but words that together make up important political manifestos and bureaucratic documents. In a drawing from earlier this year, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, Waugh has written out the text of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling. Hugely controversial, it reversed campaign finance restrictions and enabled corporations and other groups to spend unlimited funds on elections. Reversing the one-hundred-year-old law allows wealthy donors, corporations, and special interest groups to have dramatically expanded influence on campaigns with negative repercussions for American democracy and the fight against political corruption. In Waugh’s image, a pack of hunting dogs are waiting for guidance—the blind leading the blind—while a seagull seated on one hound’s back seems to be anticipating the other shoe dropping. For Redacted, 2019, Waugh copied over 350 pages of The Mueller Report. It took months of meditative labor to accomplish the work (which is huge for a drawing at some 6 x 6 feet). A nest of baby birds with mouths agape are innocently stuck in the nest until they gain maturity. For the moment they are just waiting to be fed and hoping for the best. Wasps swarm above them menacingly. While the Mueller Report laid out definitive evidence of corruption and criminal activity within the 2016 Trump election campaign, the populace is unable to take really meaningful action (until November 3, that is). Politically charged content and “traditional” imagery intersect here. The beauty and intricacy of the drawings engages us. Understanding what the text says and represents gives us pause. Artists are always interested in getting people to linger longer over their work, and Waugh’s delicate, massive, impactful drawings richly reward scrutiny. Michael Waugh (American, born 1967) Citizens United, 2020 Pen and black ink on Mylar 45 x 69 inches (114.3 x 175.3 cm) Courtesy Von Lintel Gallery Michael Waugh (American, born 1967) Redacted (The Mueller Report, volume I & II), 2019 Diptych, pen and black ink on Mylar Overall: 81 x 76 inches (206 x 193 cm.) Courtesy Von Lintel Gallery

0 Comments

Ann ShaferIt was a “I’ve been plucked from the chorus line” moment. Back in 2008, I went on a tastemaker’s tour of Brazil with a small group of curators from various American museums. It was at the invitation of the Brazilian government—they had been running these sorts of trips periodically (our guide told us he had recently hosted a group of Japanese architects). It was meant to expose us to some of their museums, galleries, foundations, and artists in hopes of future collaborations between the two countries. We were escorted on the tour by a government representative, a super nice man named Carlos. We started out in Rio de Janeiro, flew to Salvador, then ended up in São Paolo. It was an amazing trip and we saw great art.

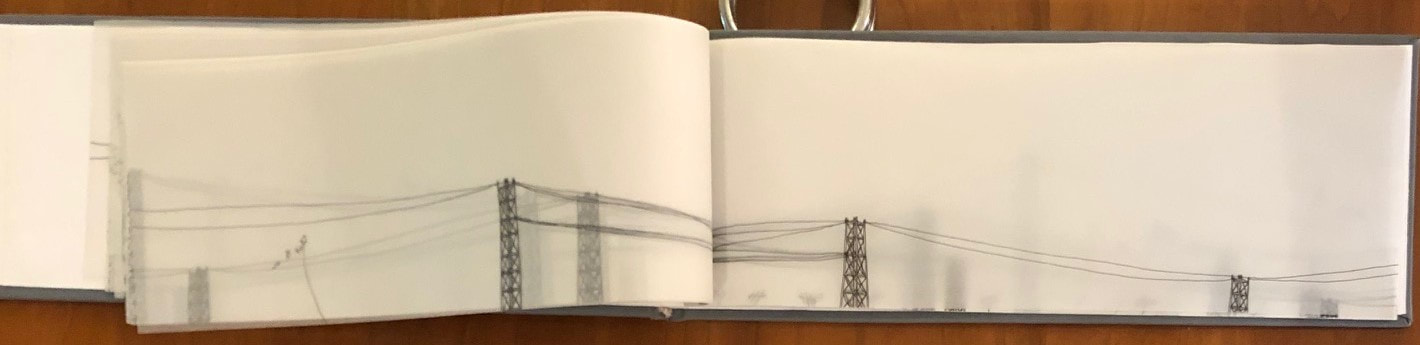

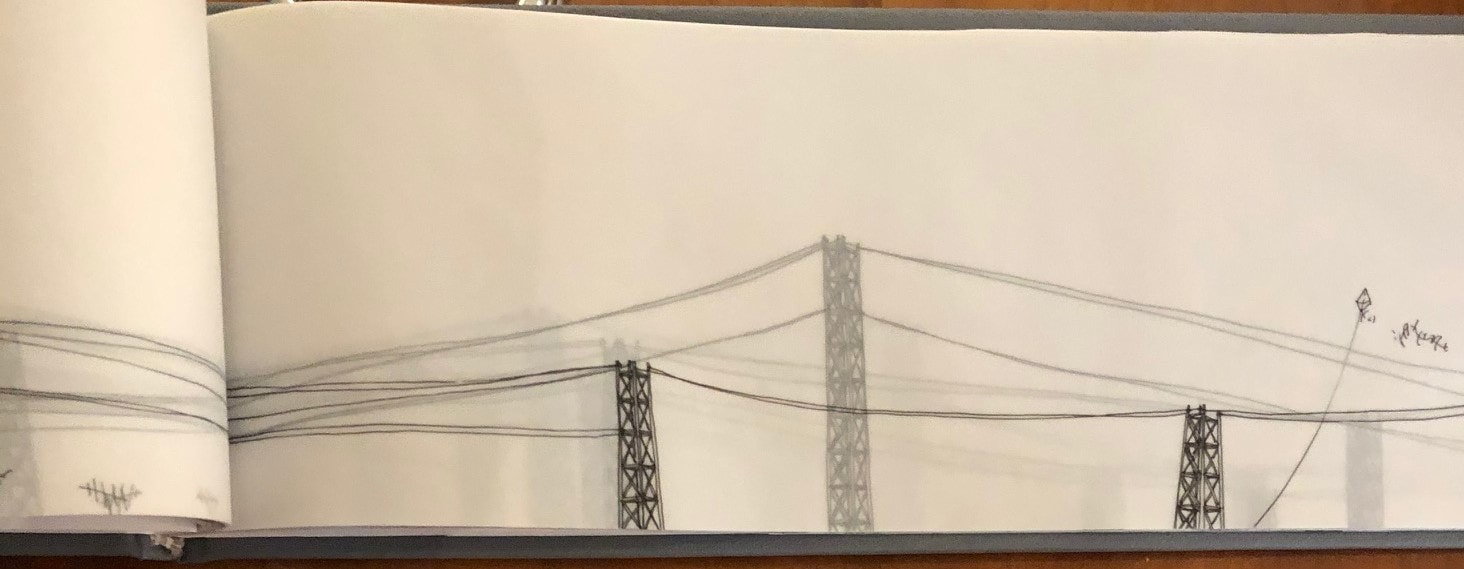

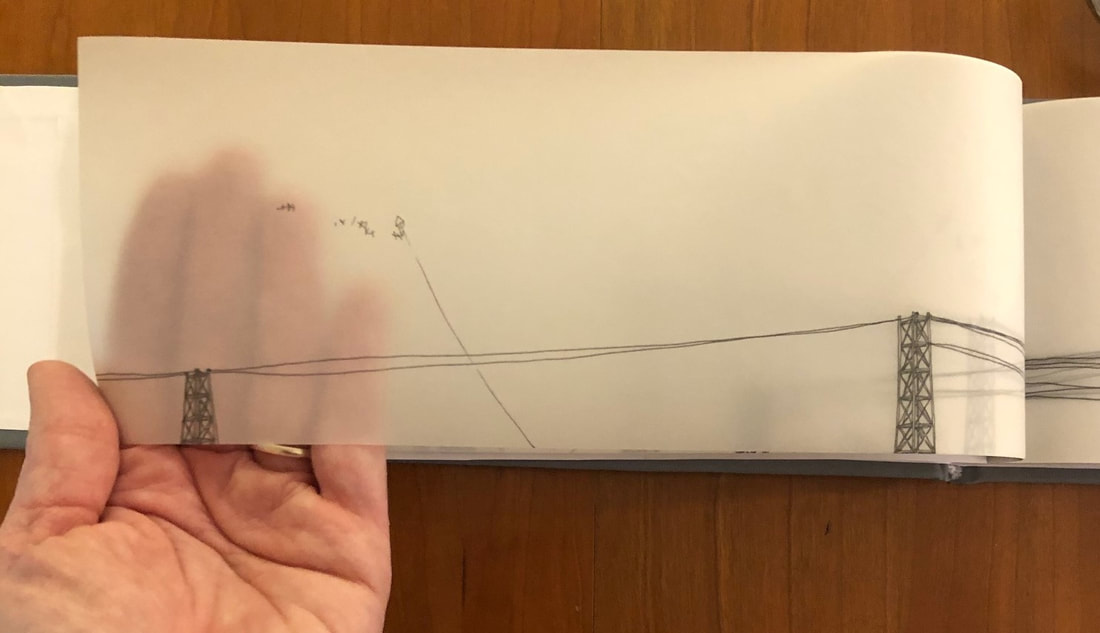

Along the way, I was introduced to a bunch of artists with whom I was unfamiliar. Some of my favorites are: Daniel Senise, Lina Kim, Alejandro Chaskielberg, Marcius Galan, Gerda Steiner & Jörg Lenzlinger, Marcello Grassmann, Oscar Niemeyer, Lygia Clark, Mira Schendel, Carlito Carvalhosa, Christian Cravo, Fayga Ostrower, Tarsila do Amaral, Nicola Costantino, Michael Wesley, Livio Abramo, Ernesto Neto, Lina Bo Bardi. When I returned to the BMA, I gave a presentation on all that we saw, which led to the only connection I was able to make. One of my colleagues, Karen Millbourne, fell in love with the work of Henrique Oliveira and included him in a show at her next museum of employment, the National Museum of African Art. He makes fantastical sculptures out of discarded plywood from urban construction sites (boards used in the fencing that blocks the view from the street) that take over spaces. São Paolo is a gigantic city that spreads out over 587 square miles. When you fly in, you see nothing but city as far as the eye can see. It just goes on and on. When we visited Galerie Vermelho, one of our last stops, I fell in love with an artist’s book by Kátia Fiera. It’s unique (there is only one of them--it is composed of drawings), and small, horizontally shaped and is filled with translucent sheets. Delicate line drawings in black marker of power lines, television antennas, and kites fill the textless pages. That you can see through each page to the subsequent pages, and that the power lines just keep going, beautifully captures the endlessness of the city, as well as its problems with pollution. While I didn’t know anything about Fiera at the time, I couldn’t pass up a perfect memento of a fabulous trip. Kátia Fiera (Brazilian, born 1976) De Passegem, 2007 Artist’s book Private collection Henrique Oliveira (Brazilian, born 1973) Desnatureza, 2011 Found plywood Galerie Vallois installation shot |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed