Ann Shafer One of the super helpful things about reproductive prints is the practice of including the “address” in which the names of the engraver, the artist of the original composition, the publisher, and maybe the benefactor appear along the bottom of the image. This convention has helped every print-room cataloguer, connoisseur, dealer, collector, scholar, and curator make sense of the thousands and thousands of Old Master prints out there in the world.

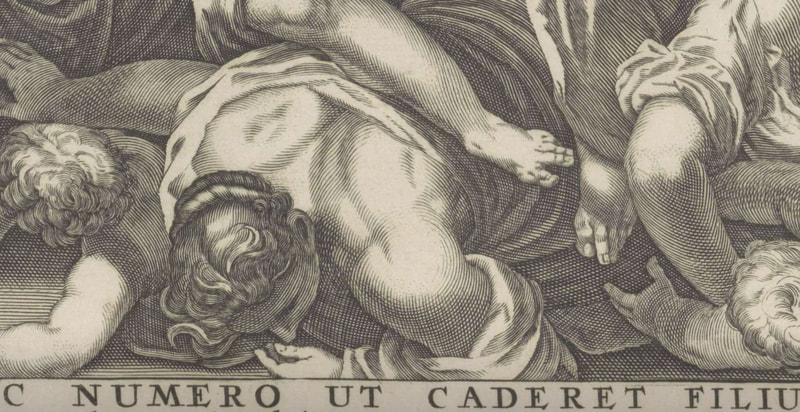

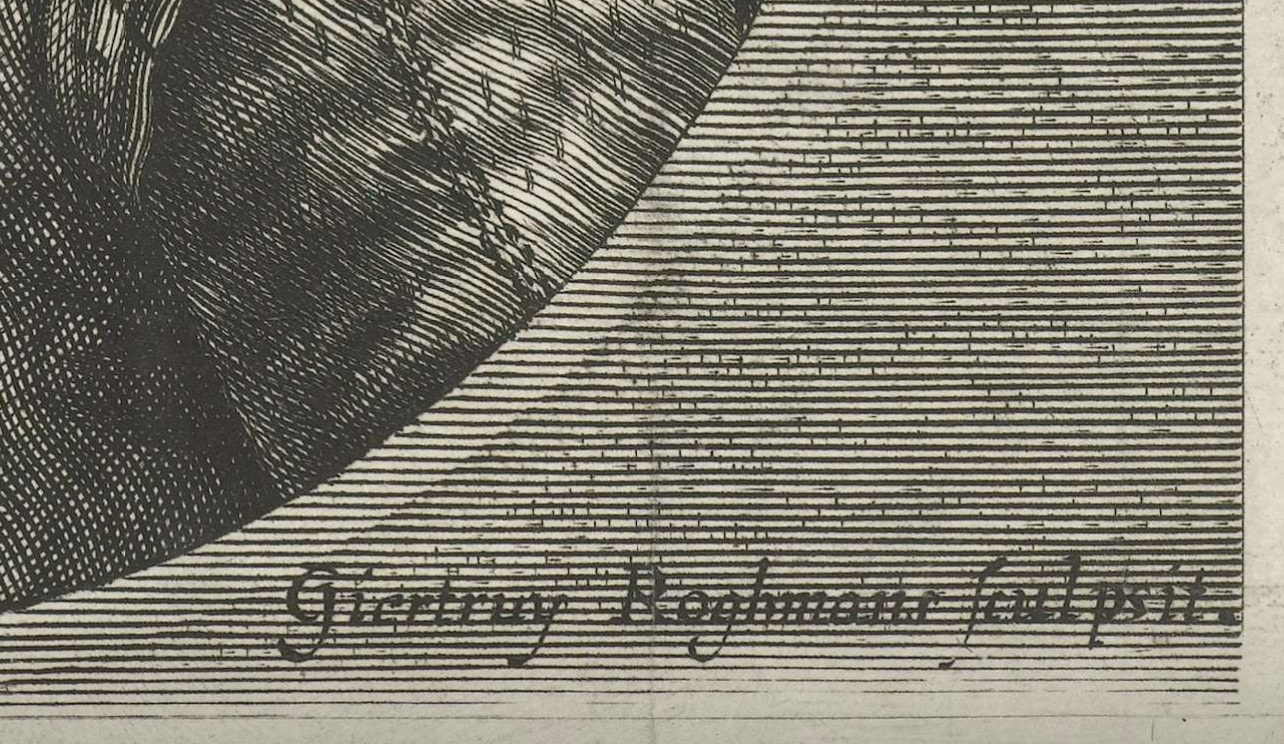

The nomenclature can be a bit confusing and some of the abbreviations mean the same things, but here are some terms frequently used in the address: Cael., caelavit: Engraved by Cum privilegio: Privilege to publish from some authority Del., delt., delin., delineavit: Drawn by Disig., designavit: Designed by Divulg., divulgavit: Published by Eng., engd.: Engraved by Exc., excud., excudit: Printed by or published by F., fac., fec., fect., fecit, faciebat: Made by Imp., Impressit: Printed by Inc,. incidit, incidebat: Incised or engraved by Inv., invenit, inventor: Designed by or originally drawn by Lith., litho., lithog.: Lithographed by Pins., pinxit: Painted by Scrip., scripsit: Text engraved by Sc., sculp., sculpt., sculpsit: Image engraved by In today’s example we have inventor (artist of the original composition), sculpsit (the printmaker/engraver), and excudit (the publisher). Making all these intricacies clear for today’s audiences is challenging. Our convention is to use the term “after” to indicate that X is the artist of the print, which is reproducing (or after) Y’s composition. Label information (we call it the tombstone information) usually omits the publisher, perhaps because it’s confusing enough as it is. In a previous post, we were introduced to Geertruydt Roghman, a printmaker best known for her series of five prints of women engaged in daily tasks. Remember, these were her own compositions. She also made reproductive prints such as The Massacre of the Innocents, which is a great example of the address helping us understand the sequence of works. So, Roghman made an engraving of The Massacre of the Innocents after a print by Aegidius Sadeler. Sadleler’s print reproduced the painting by Jacopo Tintoretto, which is in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice. So Roghman’s print is after Sadeler’s print, which is after Tintoretto’s painting. Don’t you love a twist and a turn? The subject is the Massacre of the Innocents, the biblical story of Herod who set out to kill every infant boy in Bethlehem knowing one of them would become king of the Jews. The passage is in Matthew (2:16): Then Herod, when he saw that he was mocked of the wise men, was exceeding wroth, and sent forth, and slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had diligently enquired of the wise men. It's a gruesome story and the image is relentless in its goriness and depravity. To increase the painting’s impact, there is some thought that Tintoretto would have added a plaster forearm to the bottom edge of the canvas where the woman’s arm is cut off—yes, a three-dimensional appendage. Apparently, that was a thing artists would do to enliven their paintings back then. Interestingly, the woman's arm is tucked under her in both of the prints. So how did Sadeler, a Netherlandish artist, make his copy? Did he travel to Venice to draw from the painting at the Scuola or was a drawing of it sent to him? Perhaps Sadeler made his version after yet another print of Tintoretto’s painting. But Sadeler’s version was published after Tintoretto’s death, meaning it couldn’t have been commissioned by Tintoretto to popularize the composition. Curious. We don’t know why Roghman made her version either, which is printed in reverse of both the Sadeler print and the Tintoretto painting. Does that suggest it was an exercise for practice? Was it sold in large numbers? It’s not a great and accurate reproduction if it’s backwards, right? What’s more, why make it so long after both Tintoretto and Sadeler were dead? Intriguing. #printidentification #publishersaddress #sculpsit #oldmasterprints #printsafterprints #Tintoretto #sadeler #roghman #delineavit #excudit

0 Comments

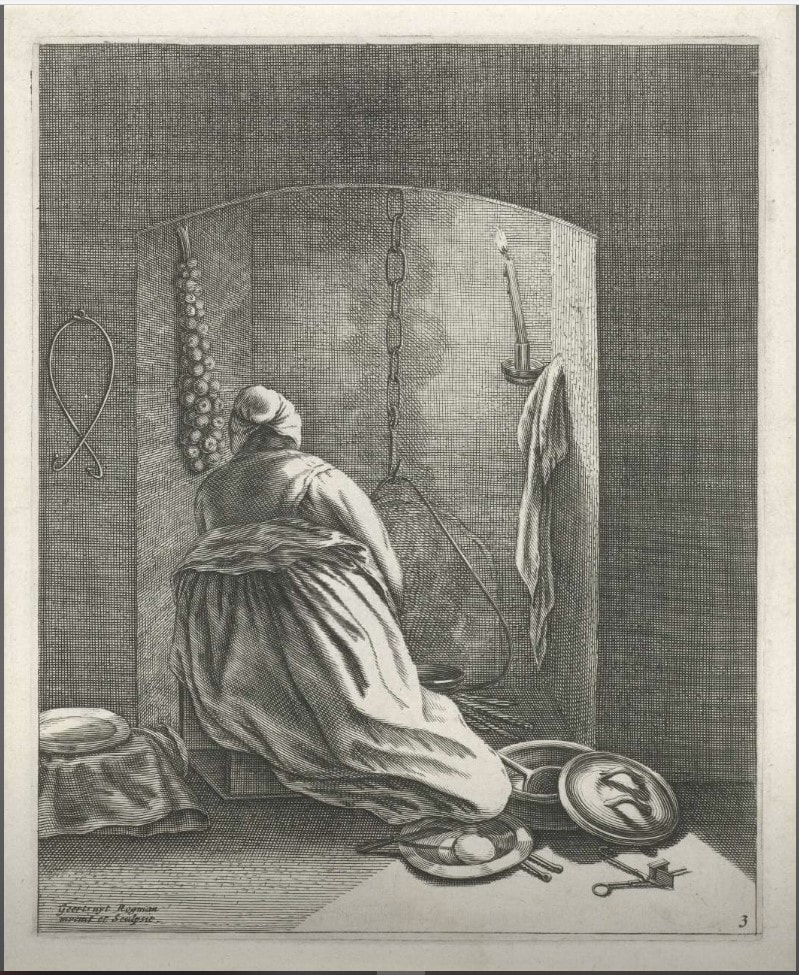

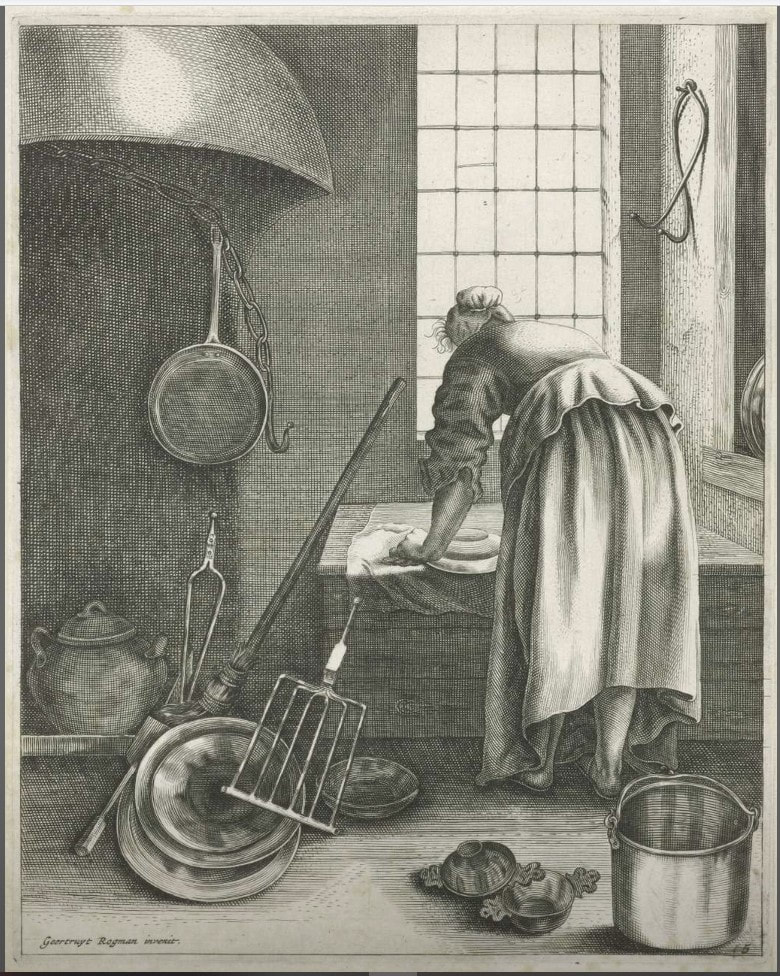

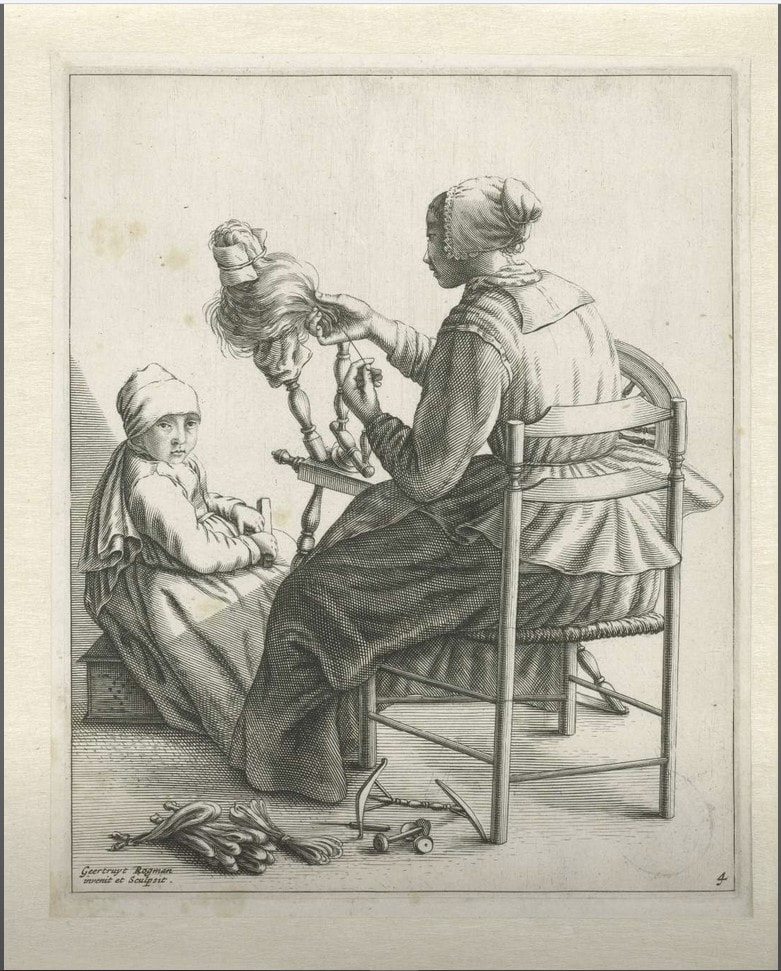

Ann Shafer During History of Prints class, it’s impossible to show everything. After each class, Tru Ludwig and I would reassess our lists and see where we could make cuts in the early periods to make room for the contemporary works at the end that the museum had recently acquired. For a while we had early Italian female printmaker Diana Scultori as the first woman to appear on the chronological list, but she got bumped off at some point (sorry Diana). If I recall correctly, the BMA’s prints by her were not great representations of her work. So, the first woman on the list became Geertruydt Roghman (Dutch, 1625–1657), an artist from an extensive artist family in Amsterdam.

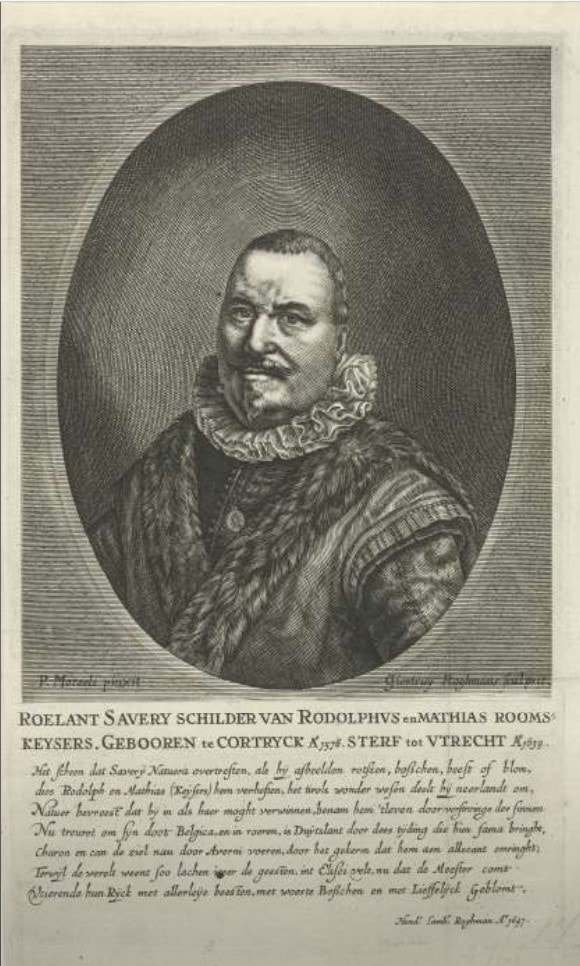

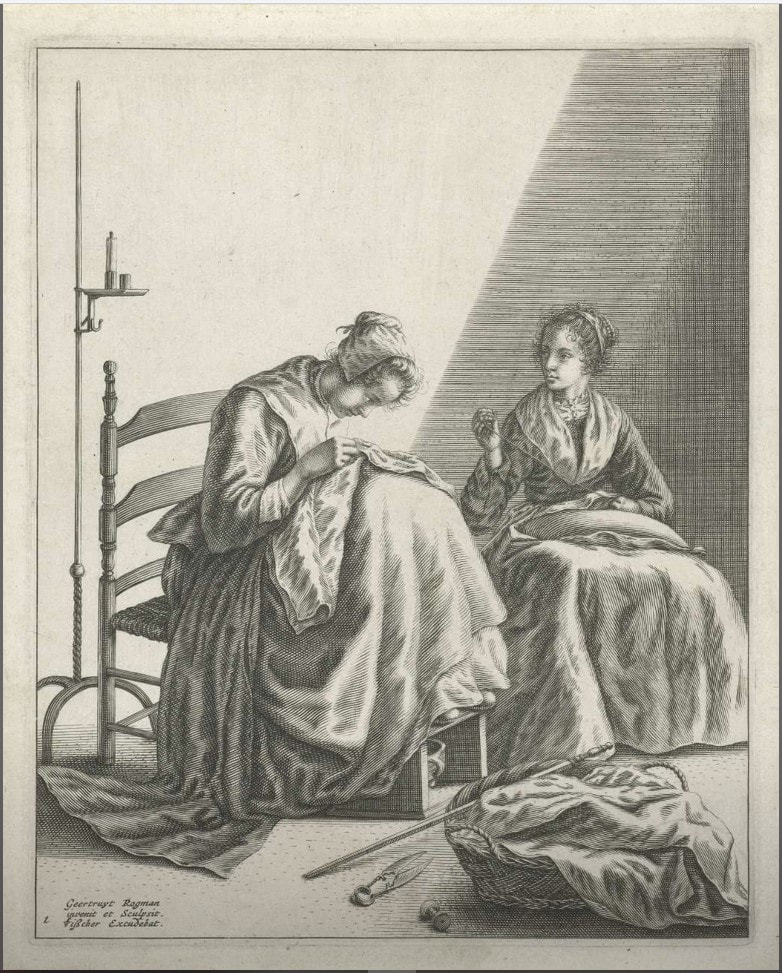

Geertruydt’s father, Hendrik Lambertsz. Roghman (1602–before 1657), was an engraver. Her mother Maritje’s father was Jacob Savery II (1593–c. 1627), a painter and etcher. Her great uncle was the Flemish painter and printmaker Roelant Savery (1576–1639), whose patron was Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612). Geertruydt’s brother Roelant (1627–1692) and sister Magdalena (1637–after 1669) were also artists and the three siblings worked with their father. As we’ve seen in our discussions of Diana Scultori and Elisabetta Sirani (see recent posts), women printmakers were frequently members of a larger artist family. Otherwise, it must have been difficult to access the world of print publishing. Roghman mostly made reproductive prints—meaning prints reproducing the compositions of other works, which can be paintings or even other prints. Her earliest known work is a portrait engraving of her great uncle Roelant, after a painting by Paulus Moreelse (1571–1638). With her brother Roelant, she made fourteen landscape etchings after his drawings. They were in their early twenties when they made these. But, Roghman is best known and celebrated for a set of five prints that are her own designs (not after some other artist’s paintings or prints) that show women engaged in daily household tasks. They are remarkable in their originality and banality. In four of them an anonymous woman is going about her day: ruffling some fabric, spinning yarn, cooking, cleaning cookware. In the fifth print, two women are sewing. Interestingly, in two of the prints, lone figures have their backs turned to the viewer. So why images of daily life rather than moralizing or religious lessons, you ask? The simple answer is that in Northern Europe (Germany, Holland, Flanders), an anti-Catholic movement was born in the sixteenth century. The Protestant movement (protest—get it?) prescribed that people did not need the Church as intercessor but they should instead form a more direct and personal relationship with God. This meant no images in churches, no religious paintings, no religious prints. (It’s more complicated than that, but you get the picture.) This anti-religious-imagery trend marked the rise of other subjects in art: portraits, still lifes, landscapes, scenes of daily life. With Roghman’s series of women doing daily tasks, we get even more of a sense of the reality of women’s daily lives. She was one of the few seventeenth-century Dutch artists to focus on ordinary women. As the Metropolitan Museum’s web site points out: “In comparing Roghman's images of household servants with those of [Gerrit] Dou and [Johannes] Vermeer, it is tempting to distinguish male and female points of view (as some critics have rather emphatically). Whatever the interpretation, it is important to bear in mind that Roghman's prints were intended for a broad art market, whereas Dou's famously expensive paintings (as opposed to the later prints after them) and The Milkmaid by Vermeer were made with individual collectors in mind.” Roghman’s prints were an abrupt departure from the religious imagery we had been covering in class up to that point. The figures are so ordinary that their meaning and importance was lost on the students. Only with context did they come to life. Of course, Tru was there to guide us every step of the way. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed