Ann ShaferThere is a holiday song with a lyric, “It’s the most wonderful time of the year,” that runs through my mind every October during New York Print Week. Encompassing three major print fairs—the IFPDA Print Fair, the Editions and Artists Books fair, and the Satellite Fair—there is a cornucopia of wonderful prints to see. There is, of course, also a lot of attendant programming, dinners, and socializing. Oh, and we always try to hit various galleries and museum exhibitions. It’s a super busy week, exhausting and energizing, and it’s so fun to catch up with all the artists, printers, and publishers we’ve gotten to know over the years.

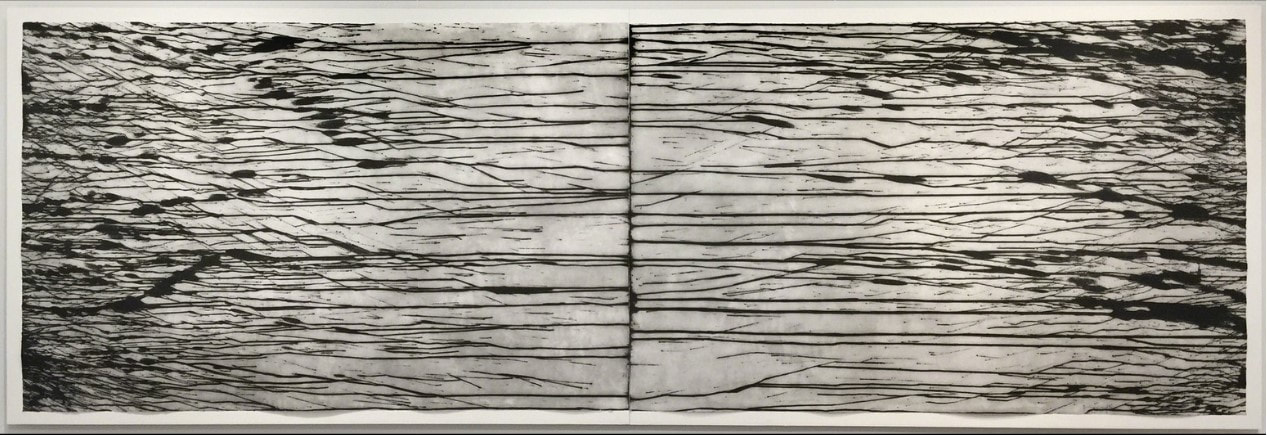

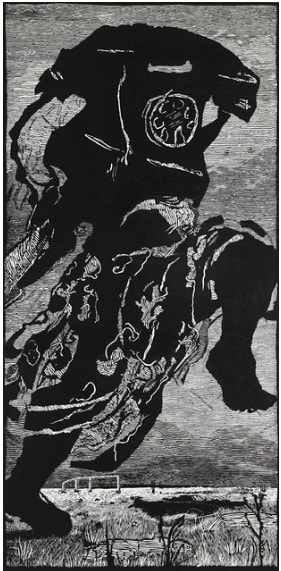

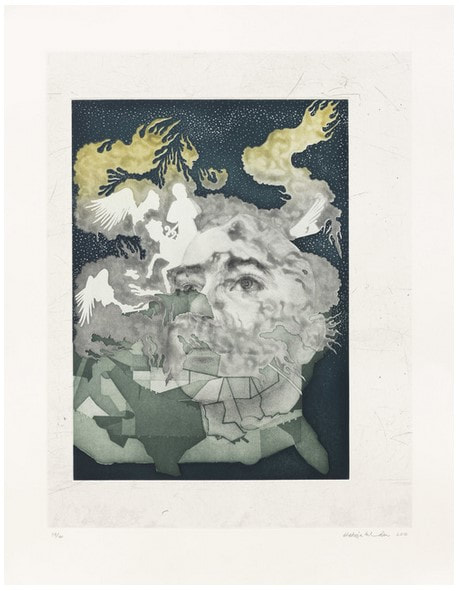

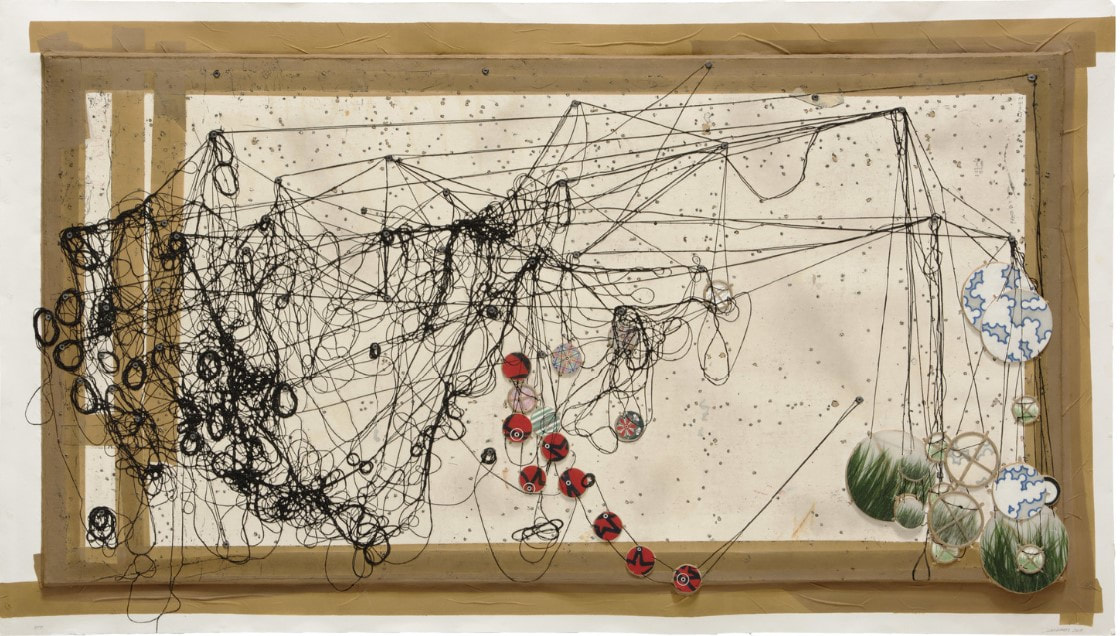

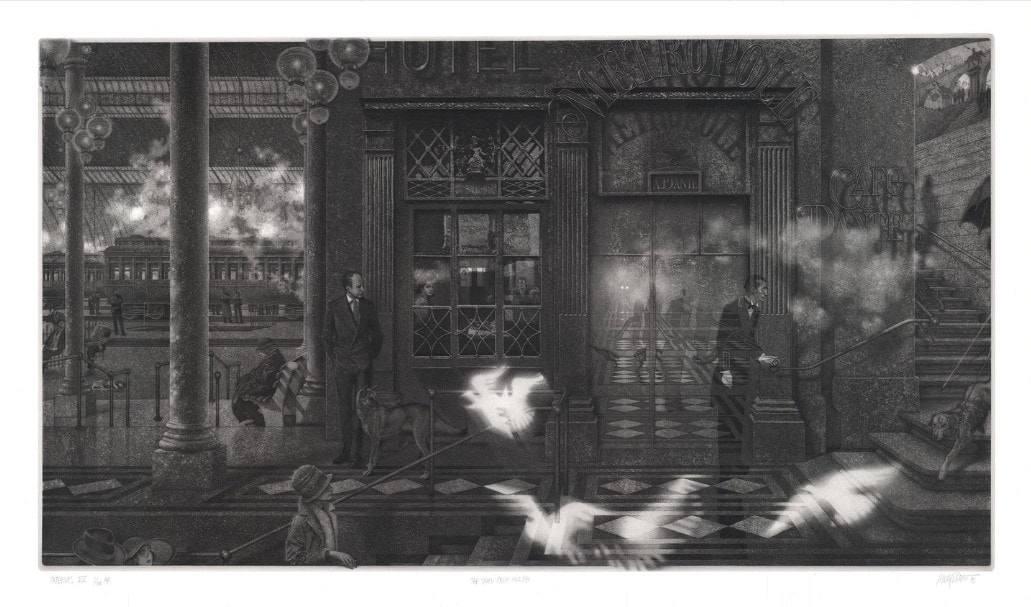

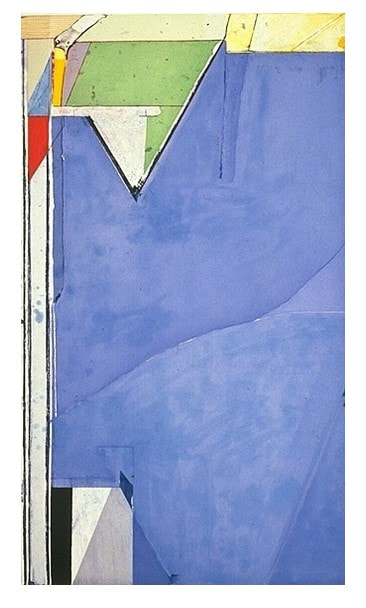

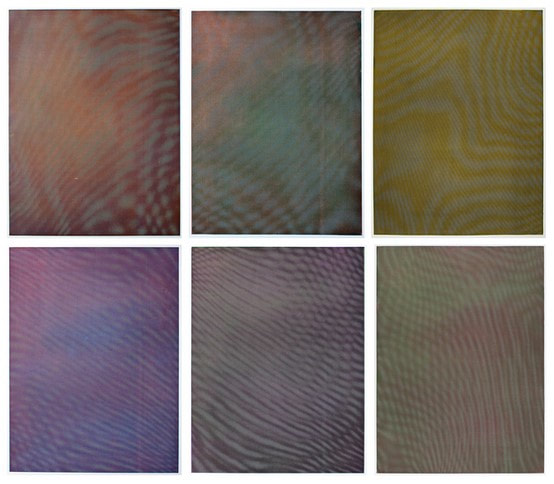

Because of the pandemic, New York Print Week 2020 is occurring virtually. While the IFPDA has really stepped up to the plate with a month’s worth of daily virtual artist talks and studio tours, and each fair has set up online viewing rooms, there is nothing like being there in person. I will always believe that one must see works of art in person to really absorb them accurately. As a curator on the hunt for contemporary (ish) works on paper, New York Print Week is one-stop shopping. At the IFPDA fair alone there are usually ninety vendors. I thought it would be fun to pick out favorite works from each fair. The caveat being, of course, that seeing the works in person might change my mind. Here’s a group from the IFPDA Print Fair in no particular order. Derrick Adams Self Portrait on Float, 2019 Woodblock, gold leaf, collage 40 × 40 in (101.6 × 101.6 cm) Tandem Press Richard Long Speed of the Sound of Loneliness, 2014 A two panel carborundum relief, both panels printed in Black/Ultramarine Blue ink mix 47 3/4 × 152 3/4 in (121.3 × 388 cm) Jonathan Novak Contemporary Art William Kentridge Telephone Lady, 2000 Linoleum cut 85 × 47 in (215.9 × 119.4 cm) Gallery Neptune & Brown Shahzia Sikander Portrait of the Artist, 2016 One in a suite of four etchings 27 × 21 in (68.6 × 53.3 cm) Pace Prints Jacob Hashimoto Tracing the Ever-fragile Balance of Dreamless Silence: This Unruly Forest, These Imaginings, and the Final Exhalation, 2019 Mixografia print on handmade paper 34 1/2 × 61 1/2 in (87.6 × 156.2 cm) Mixografia Peter Milton Interiors VI: The Train from Munich, 1991 Resist-ground etching and engraving, 20 × 35 5/8 in (50.8 × 90.5 cm) The Old Print Shop Walton Ford Benjamin's Emblem, 2000 Etching 44 3/16 × 30 3/8 in (112.2 × 77.2 cm) Susan Sheehan Gallery Richard Diebenkorn High Green, Version I, 1992 Color spit bite and soap ground aquatints with soft ground and hard ground etching and drypoint 52 × 33 in (132.1 × 83.8 cm) Crown Point Press Tom Marioni Drawing a Line, 2012 Drypoint with plate tarnish printed in sepia and black 54 × 16 in (137.2 × 40.6 cm) Crown Point Press Tauba Auerbach Mesh Moire I-VI, 2012 Suite of six color softground etchings on Somerset white paper 86 × 98 in (218.4 × 248.9 cm) Carolina Nitsch Contemporary Art Charles Gaines Numbers and Trees, Tiergarten Series 3: Tree #1, April, 2018 Color aquatint and spitbite aquatint with printed acrylic box. 41 1/4 × 32 × 3 1/2 in (104.8 × 81.3 × 8.9 cm) Paulson Fontaine Press

0 Comments

Ann Shafer For all that museums are going through at the moment—financial hardships due to covid-19 closures, reckoning with their ingrained colonialism, rewriting the art historical canon to include women and BIPOC, reckoning with a spate of questionable deaccessioning, dealing with issues of social justice and diversity both externally in programming and internally with staff composition—I still believe in the transformative power of art.

If you have been following along, you know that there have been three times in my life when my jaw dropped in response to a work of art. The first was in a college art history class looking at a slide of an Edouard Manet still life of lilacs in a vase. The second time was in the tiny garden behind Charles Demuth’s Lancaster home over which an enormous church steeple looms. I've written posts about both of these moments; hope you check them out. The third time my jaw dropped was while standing in front of Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas, 1656, at the Prado in Madrid. Of the three moments, this was the most surprising occurrence for me. My love for Demuth is such that I spent my senior year in college writing my thesis on him. And who doesn’t love a beautiful still life by Manet? My reaction to Las Meninas surprised me because I have no training in art of the seventeenth century, have never taken a class in Spanish art of any sort, and only know what I’ve read in the skimmiest way possible. The combination of my lack of knowledge and my reaction to it means, for me, Velasquez’s painting is the ultimate example of transformative art. I have avoided writing about the painting because of my lack of knowledge. There’s a lot to pull apart while attempting to get at its meaning and why it is visually so spectacular. But recently a link to an article about it crossed my feed. So, here’s that article, which I encourage you to check out. Also, if you ever find yourself in Madrid, don’t miss Las Meninas at the Prado. Diego Velasquez (Spanish, 1599-1660) Las Meninas, 1656 Oil on canvas 318 x 276 cm (125.2 x 108.7 in) Museo del Prado, Madrid Ann Shafer Ok. It has been a seriously long time since I’ve been able to not only write about art but also offer a chance to see it with me, in private, in person (masks required, obvi). Shoot me a message if you are intrigued. So, no more looking backward, only forward. As a part of my new gig, I’m writing about the exhibitions mounted at Full Circle’s two galleries, Catalyst Contemporary (523 North Charles Street) and Full Circle Gallery (33 East 21st Street). Here’s my first go at the exhibition at Catalyst by Baltimore County retired doctor Jed Smalley, which closes on October 31.

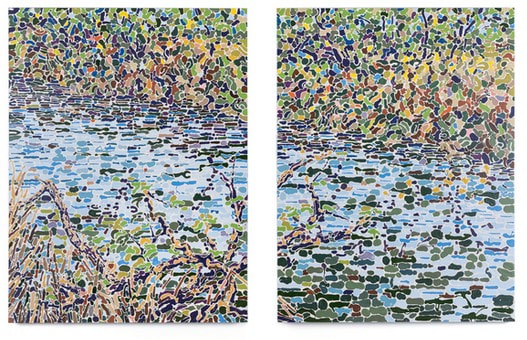

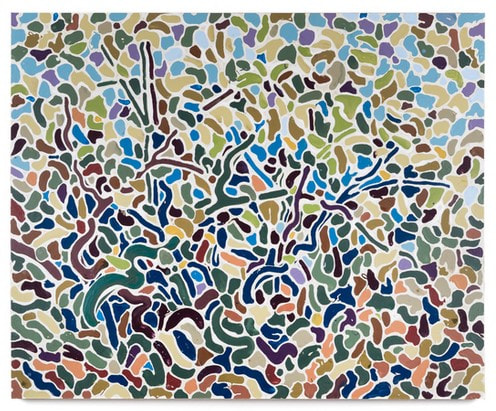

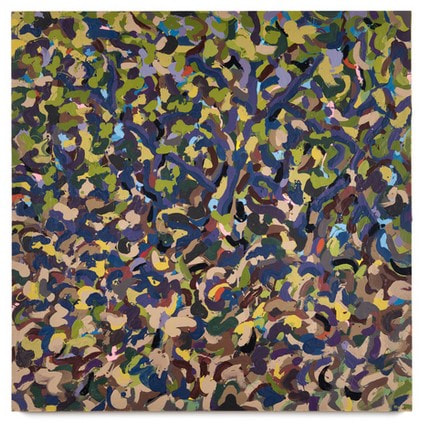

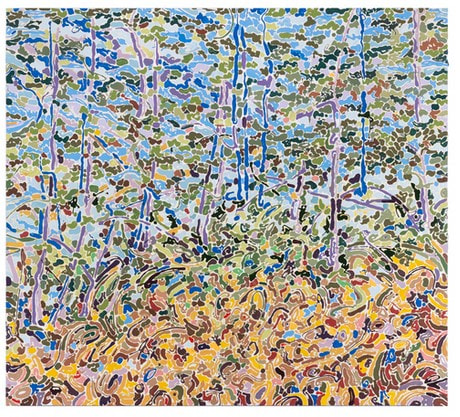

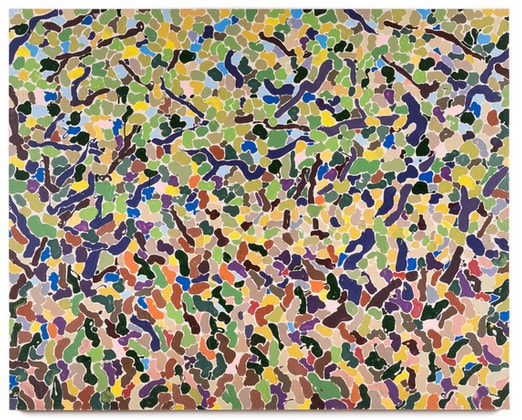

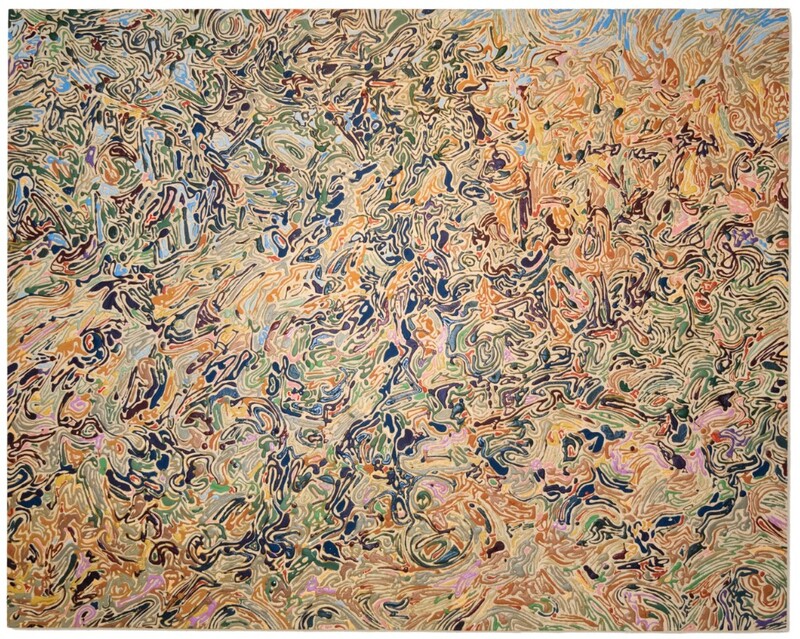

Where do control and chance meet? Arthur Jedson Smalley is an artist who is deeply committed to this balancing act. In fact, it is an essential part of his creativity. Smalley makes sculptures in wood, using both found and milled lumber, which form organic Möbius strips, and paintings of landscapes using latex house paints dripped from brushes attached to long sticks. The tension between the artist’s hand and the inherent tendencies of the medium tips one way or the other within the course of making the work. It is only in the struggle between artist and material that Smalley is uncomfortable enough to be comfortable with the results. Smalley starts his paintings with a particular landscape in mind (often Baltimore County), one that he is deeply familiar with and visits often to study its forms and the way light plays across its features (only very rarely does he paint en plein air). Working with the painting surface (he uses artists’ board not canvas) lying on the floor, Smalley drips colors onto the board, all the while trying to control what that daub or drip does. Because of the length of the tool of application and the viscosity of the paints, Smalley must embrace the pooling of the paint, accepting and counting on any accidents. He says, “paintings are compromises,” and admits that he tries to paint from his subconscious, letting go of any predetermined ideas save for the generalized landscape giving it visual structure. First, several spots of color are placed to begin the framework of the image. Next begins a ballet of color choices and placements of subsequent drips, which must interlock with the one to which it is adjacent. Accidents are accepted and desired. While it may sound counterintuitive—would not an artist wish for complete control of his/her facility—for Smalley, it is precisely this tension that enables the works to be made. He admits that every attempt at a more conventional method of accomplishing a landscape falls flat. In the battle for control, beautiful scenes emerge composed of daubs of colors that at once suggest specific and generalized landscapes. Smalley is an exceptional colorist. His palette is widely varied and works perfectly. The landscapes’ dappled light achieved through drips of colors makes the paintings sparkle and creates movement. They elicit a feeling of walking through woods on a bright sunny day. The paintings are in the vein of the French Pointillists George Seurat and Paul Signac in that daubs of formless paint and juxtaposed colors coalesce to create shadows, tree limbs, and streams. They take pure advantage of the human brain’s ability to fill in the gaps and change depending on one’s distance from the surface. While one can focus on the composition that reveals itself, one can also shift focus to the negative spaces between the daubs, changing the composition yet again. At once abstract and completely readable as landscape, Smalley’s works are pure delight belying the struggle and tension that goes into their creation. While the artist’s struggle between control and accident combine to offer atmospheric walks in the woods in the paintings, the sculptures are concerned with different aspects of chance. Each sculpture forms a self-contained loop of wood. Sometimes natural segments of thick branches are joined in tight, sinewy jumbles, their construction masked. Sometimes blocks of 4-x-4-inch pieces of lumber are cut in trapezoidal shapes and joined without hiding the sculpture’s construction. Depending on the angles of the cuts, the next piece added takes the form in a new direction. In their continuousness, they are versions of a Möbius strip in which the beginning and end are one and the same. They are at once organic and constructed, natural and unnatural, beautiful and rough, whimsical and serious. The surfaces of Smalley’s paintings glisten and are tactile. They change depending on one’s viewpoint and are both light and airy and dense and saturated. The sculptures are elegant and curvy, disjointed and smooth, confounding and gentle in their loveliness. Bursting with potential energy, they exhibit a variant on the tension present in the paintings. Smalley’s talents are fully on display in this body of work. The works are worth the time to absorb their beauty comprised of surprising elements that come together in symphony. Ann Shafer Recently I wrote about editions and meta prints focusing on two works: Bill Thompson’s Edition and Fiona Banner’s Book 1/1. The latter work was published by the artist and the Multiple Store, which is no longer in business. In fact, finding an image of Book 1/1 for the post necessitated digging into the Wayback Machine run by web.archive.org with which one can find archived web sites. Very useful. The Multiple Store was founded in 1998 by Nicholas Sharp and Sally Townsend (it shuttered in 2016). According to the founders: “Our aims were to commission new work by some of the best contemporary British artists, to encourage a culture of collecting by selling our editions as inexpensively as possible; and to provide opportunities for artists to explore new materials and processes.” That’s a mission I can get behind. Back when Ben Levy and I ran the BMA’s Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair, we searched for possible participants at several print fairs that occur in New York in the fall. Ben and I were eager to bring in vendors that made or published the works they had on offer. That way, the public would have the opportunity to speak directly with the people who made the art while fulfilling the museum’s goal to educate people. At one of the New York fairs, the Editions and Artist Books Fair, we had the pleasure of meeting Nicholas Sharp who was showing the multiples published by the Multiple Store. Nick was charming and devoted to his mission, and we loved the objects they published. Ben and I tried our best to convince him to come to Baltimore for our Print Fair, but we could never make it work, and Baltimore missed out. The Multiple Store published intriguing multiples—the sculptural version of print editions. One stand-out object was a kaleidoscope by Yinka Shonibare MBE who is best known for his tableaux featuring mannequins dressed in western costumes made out of Dutch wax-printed cotton that appears to be African in style. That substitution plays into Shonibare’s investigation of the tangled economic and political interrelationships between Africa and Europe. For the Multiple Store, Shonibare created a kaleidoscope, a nod to nineteenth-century Victoriana. The exterior is decorated with a pattern echoing the Dutch fabrics he uses in his larger works. And that’s where the subtleness ends. The shiny brass top, where a viewer looks into the kaleidoscope, is in the form of the tip of a phallus, all bright and shiny. The image that is splintered within is an edited version of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in which the figure of Venus has been replaced with a rather well-endowed Black male nude. It’s a peep show, if you will, and a total turn-about of the male gaze. Shonibare said of the work: “I intended this piece as both playful and serious: it looks like an adult sex toy, but it is also a serious comment on patriarchy, and the objectification of the female body in the media, by what film theorist Laura Mulvey called the ‘male gaze.’ Kaleidoscope was meant as ‘one for the ladies’…though I think it may appeal to some gentlemen too.” I was so sorry Nick felt he had to close the Multiple Store. As it was a side project for the lawyer, perhaps one can understand. But still. Yinka Shonibare MBE (British-Nigerian, born 1962) Published by The Multiple Store Kaleidoscope, 2014 Cast brass, digitally printed cotton, lacquer, mirror, lens, glass, perspex, oil 80 x 80 x 270 mm. (10 ½ x 3 x 3 in.) Yinka Shonibare MBE (British-Nigerian, born 1962) How to Blow up Two Heads at Once (Ladies), 2006. Two life-size mannequins, two guns, Dutch wax-printed cotton, shoes, and leather riding boots Overall 63 x 96: 1/2 x 48 inches, each figure: 63 x 61 x 48 inches Collection of Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. Photo by Stephen White, © Yinka Shonibare MBE, courtesy the artist, James Cohan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London  Yinka Shonibare MBE (British-Nigerian, born 1962). How to Blow up Two Heads at Once (Ladies), 2006. Two life-size mannequins, two guns, Dutch wax-printed cotton, shoes, and leather riding boots. Overall 63 x 96: 1/2 x 48 inches, each figure: 63 x 61 x 48 inches. Collection of Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. Photo by Stephen White, © Yinka Shonibare MBE, courtesy the artist, James Cohan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed