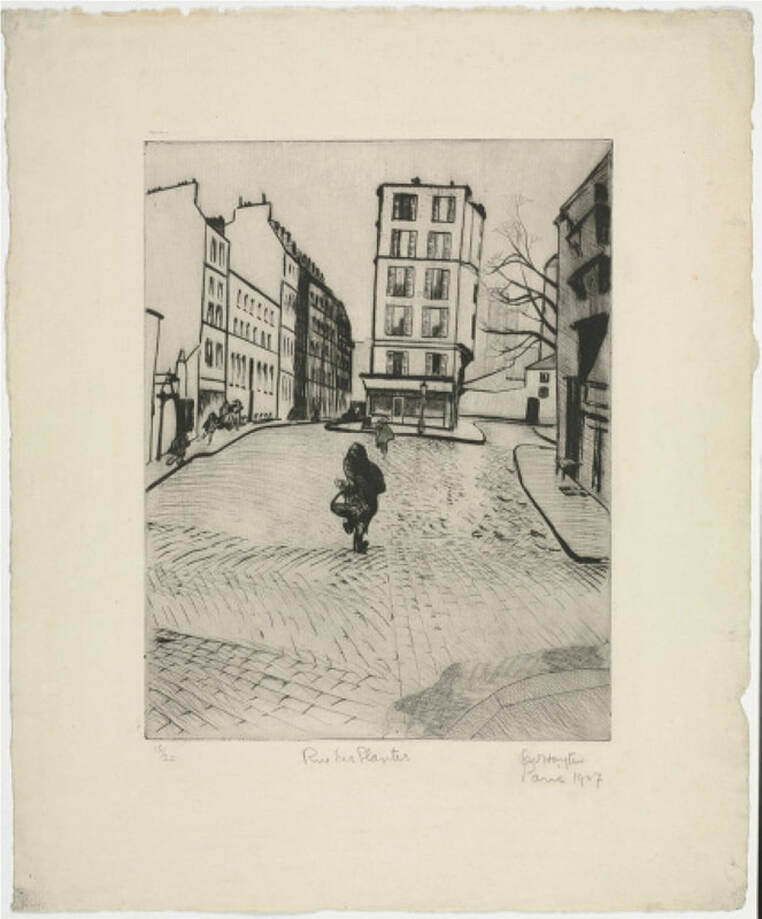

Ann ShaferI’ve been teaching myself Adobe’s video editing software, Premiere Rush. Today is the debut of my first attempt, a very short video on Stanley William Hayter’s Rue des Plantes, 1926. For our epic research trip to Paris in 2015, Ben Levy, Tru Ludwig, and I had a lot on our to-do list related to the Hayter exhibition. First on the list was to photograph and film the printing of Hayter’s Torso, 1986, at Atelier Contrepoint, which I wrote about in another post. Second was to interview Désirée Hayter on video. Third was to find and photograph as many locations of the Atelier as possible (it moved a bunch of times). And fourth was to find, photograph, and videotape the locations that appear in Hayter’s series Paysages urbains, 1930 (more on that in another post). While doing the last, I added finding the site of Rue des Plantes to the list. Rue des Plantes is a lovely early drypoint by Hayter depicting a simple street scene in the 14th arrondissement. In it a lone figure carrying her daily market purchases walks toward a building that oddly is situated in the middle of a cobblestone street. Finding the site wasn’t too hard, but finally laying our eyes on it sparked our adrenaline. Ben set up the video equipment intent on taking some B-roll for an eventual video for the exhibition website. With the camera rolling, suddenly an older woman carrying her market purchases wandered into the frame. The three of us must have looked like lunatics gesturing to each other madly but silently so as not to be recorded on the tape. It couldn’t have been more perfect. Finally, I’ve pulled a short video together showing this golden moment, which thrills me still. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988) Rue des Plantes, 1926 Drypoint Sheet: 400 x 328 mm. (15 3/4 x 12 15/16 in.) Plate: 267 x 208 mm. (10 1/2 x 8 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Bequest of Ruth Cole Kainen, Chevy Chase, Maryland, BMA 2011.263

0 Comments

Ann ShaferI’m a super fan of intaglio printmaking—intaglio refers to printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink—and I always wanted to do a series of shows on techniques, starting with, of course, intaglio. (Sorry folks, lithography would be last; well, maybe screenprinting.) Stanley William Hayter was a great practitioner of intaglio printmaking, as were all of the artists who worked with him at Atelier 17. Many of them established or ran university printmaking departments, including Gabor Peterdi, who taught at Yale from 1960 to 1986. One of Peterdi’s students was Peter Milton, who must stand as one of the great intaglio printmakers of the latter part of the 20th century.

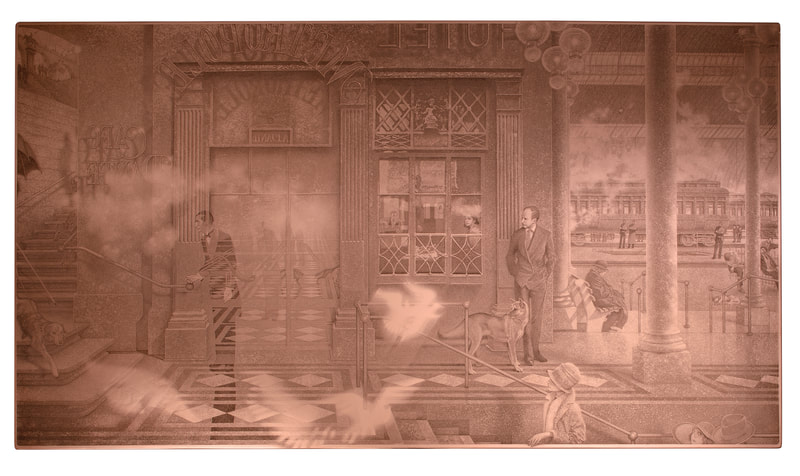

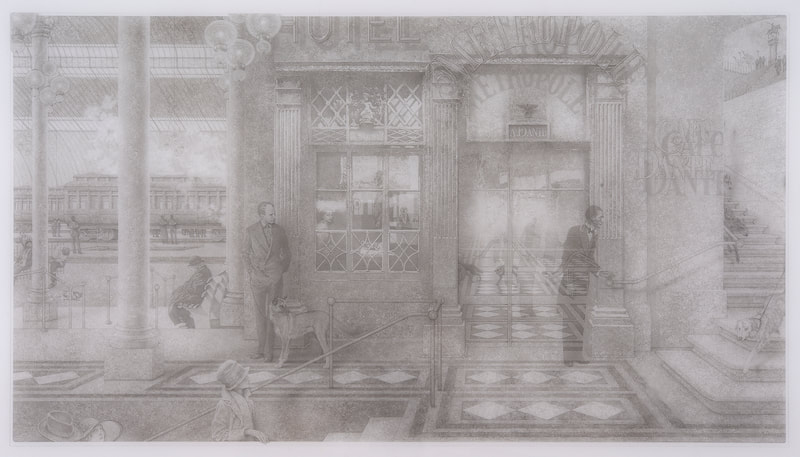

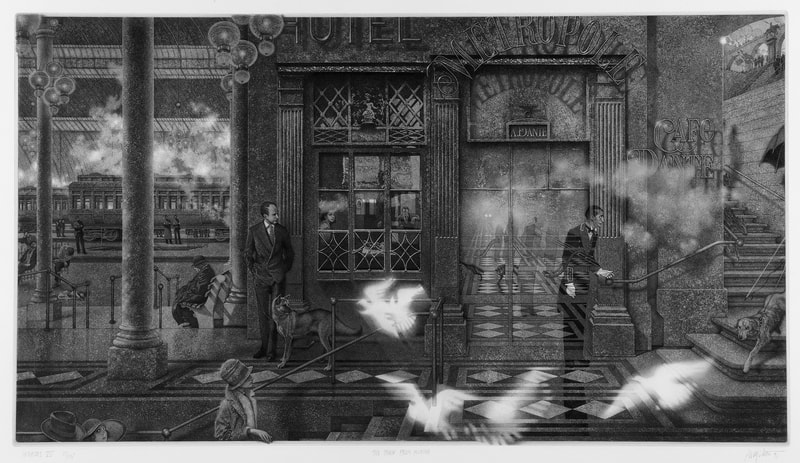

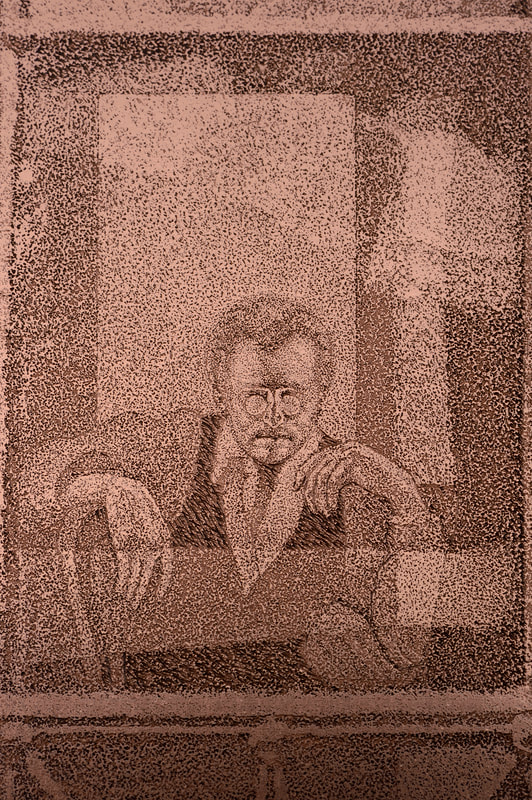

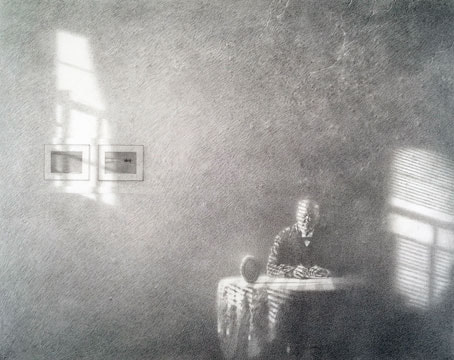

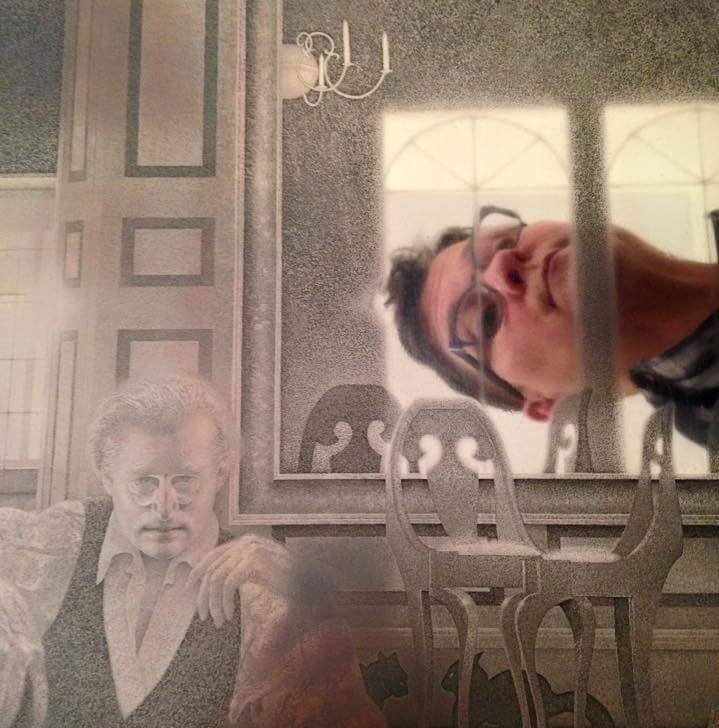

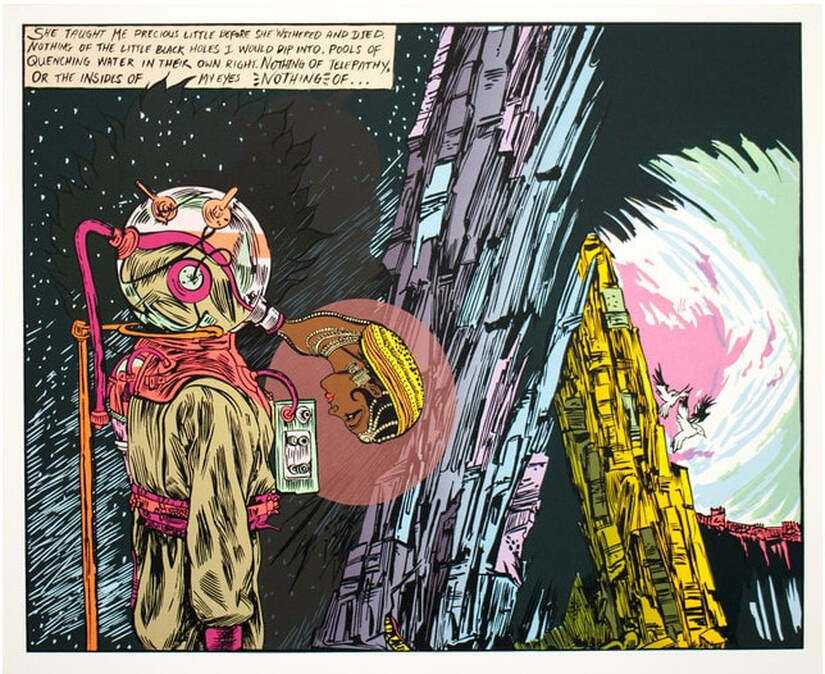

The BMA has a handful of Milton’s prints. One of the most spectacular, Interiors IV: Hotel Paradise Café (1987), is mindblowing for students in MICA professor Tru Ludwig's History of Prints classes. Upon its unveiling one would hear choruses of “wow!” along with mutters of “it’s so not fair.” Its intricacies have both inspired and depressed young printmakers. Tru and I are both fans and when we had the opportunity to hear Milton speak at Jane Haslem’s Washington, D.C., gallery, we jumped at the chance to meet him. After the talk we approached and he and Tru bonded over everything from techniques to history to all the esoteric details that appear in his prints. It was also there that I spied one of his drawings for his series The Aspern Papers, which I eventually acquired for the BMA—more on that in another post. During their conversation, Peter told Tru that he considered the copper plates to be the most beautiful things he makes. The lightbulb went off and the next thing we knew, Tru and I were working together with James Archer Abbott, then director of Evergreen Museum and Library, to curate an exhibition of Milton’s plates, prints, and preparatory drawings. Several trips were made to Milton’s New Hampshire studio and home, where we were welcomed by Peter and his lovely wife, Edith. There we got to interview him, see where the magic happens, and select the plates and other works to be included in the show. To my mind, Milton’s Interiors series is his most important. We included five of the seven plates from that series including The Train from Munich (1995), which focuses on Edith’s 1939 departure from Germany as one of 10,000 children sent on a Kindertransport train taking unaccompanied Jewish children to the United Kingdom for the duration of the war. [Edith and her sister lived with a British family for seven years and she eventually published an excellent memoir about that time called Tiger in the Attic (a NYT review is here: https://bit.ly/MiltonTigerinAttic).] The Train from Munich graces the cover of the catalogue produced for the Evergreen show and it is written about in depth therein. The link to the PDF catalogue is here: https://bit.ly/MiltonCatalogue. Working on the show, I think Tru had the most fun job. He was the muscle responsible for polishing the copper plates. This is no easy task and takes patience and perseverance. In the end, we both agree with Peter. The copper plates are stunningly beautiful and reveal things, objects, and moments that are easily missed in the printed versions. It was an honor to work with this titan of printmaking. And, we owe one last thank you to Jim Abbott for letting us make a dream come true. Ann ShaferWhen the museum acquired Chitra Ganesh’s work, I already had the seed of a show growing in my mind. I had been asked to come up with an exhibition drawn from the collection featuring works by artists of color. This is problematic on many levels. I have always believed that separation is sometimes useful, but that integration must be the goal. In any case, the works available for a show of that sort lacked any thematic cohesion. At the same time, I’d had many MICA students inquire about seeing works from the storeroom that reflected a graffiti or comic book sensibility. The collection did not have much to offer. It took time and several acquisitions to bring together an exhibition that focused on the theme of alternate realities—artists looking at real-world problems through visual fantasies, comics, sci-fi. Ganesh’s gorgeous print fit the bill beautifully and was installed along with prints by Trenton Doyle Hancock, Wangechi Mutu, Toshio Sasaki, Enrique Chagoya, William Villalongo, iona rozeal brown, Raymond Pettibon, and Amy Cutler. On Paper: Alternate Realities was on view September 21, 2014–April 12, 2015. It was the most organically diverse show of my career and remains one about which I feel extremely proud.

I love a print that looks cool and asks more questions than it answers. Chitra Ganesh’s Away from the Watcher is a colorful combination of screenprint and woodcut that features an enigmatic figure at left (in a scuba or space suit—you decide) who seems to be exhaling an Indian goddess figure, while watching a city on a hill possibly being destroyed. Along the top left is a comic-strip-style thought bubble that reads: “She taught me precious little before she withered and died. Nothing of the little black holes I would dip into. Nothing of telepathy, nor the insides of my eyes. Nothing of…” This image raises many questions: Is somebody inside the scuba/space suit—isn’t it propped up? Is the Indian goddess figure being expelled or inhaled? Are we underwater or in outer space? What do the small winged creatures signify? What calamity has befallen the city at right? The somber melancholy of the text seems at odds with the dynamic depiction of the planet’s fissures, as well as the brilliant color and energetic comic-book style of representation. These alternate moods and narratives clash and connect in a newly constructed vision of the future. Chitra Ganesh (American, born 1975) Printed and published by Durham Press Away from the Watcher, 2014 From the series Architects of the Future Woodblock and screenprint 629 × 797 mm. (24 3/4 × 31 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of an Anonymous Donor, BMA 2014.29 Ann ShaferIf ever I turned my attention to making art instead of writing about it, I would pull out my watercolors and brushes and head outdoors. It’s hard to imagine a world when that wasn’t possible—but it wasn’t so long ago that the first paints in tubes became commercially available. The first premixed watercolors were introduced to the market in England in the 1760s, but it wasn’t until the 1840s that those little tubes we know today were invented.

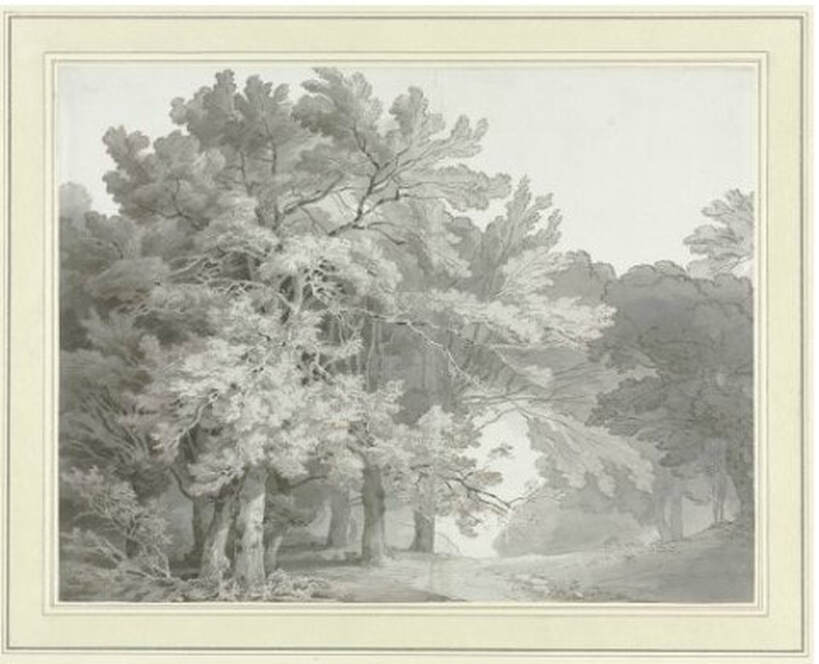

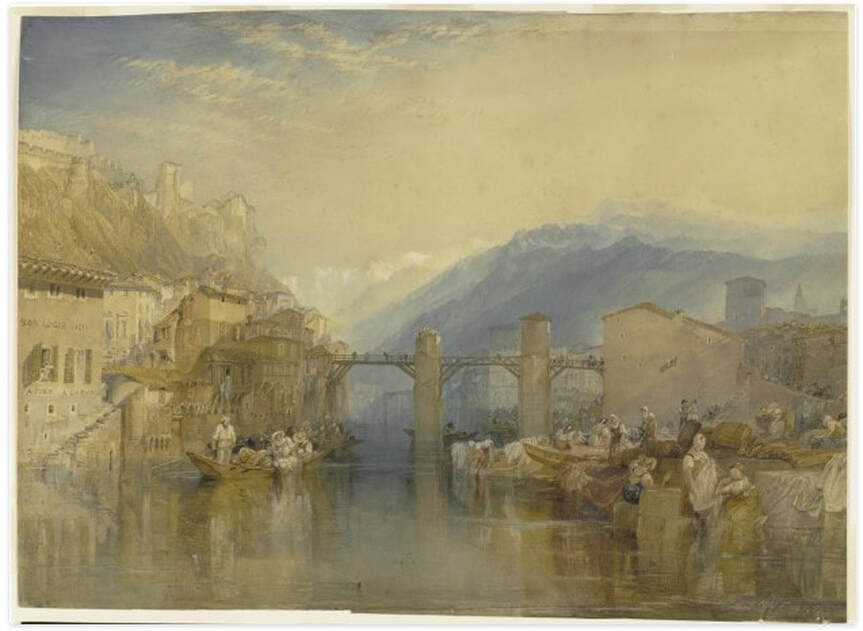

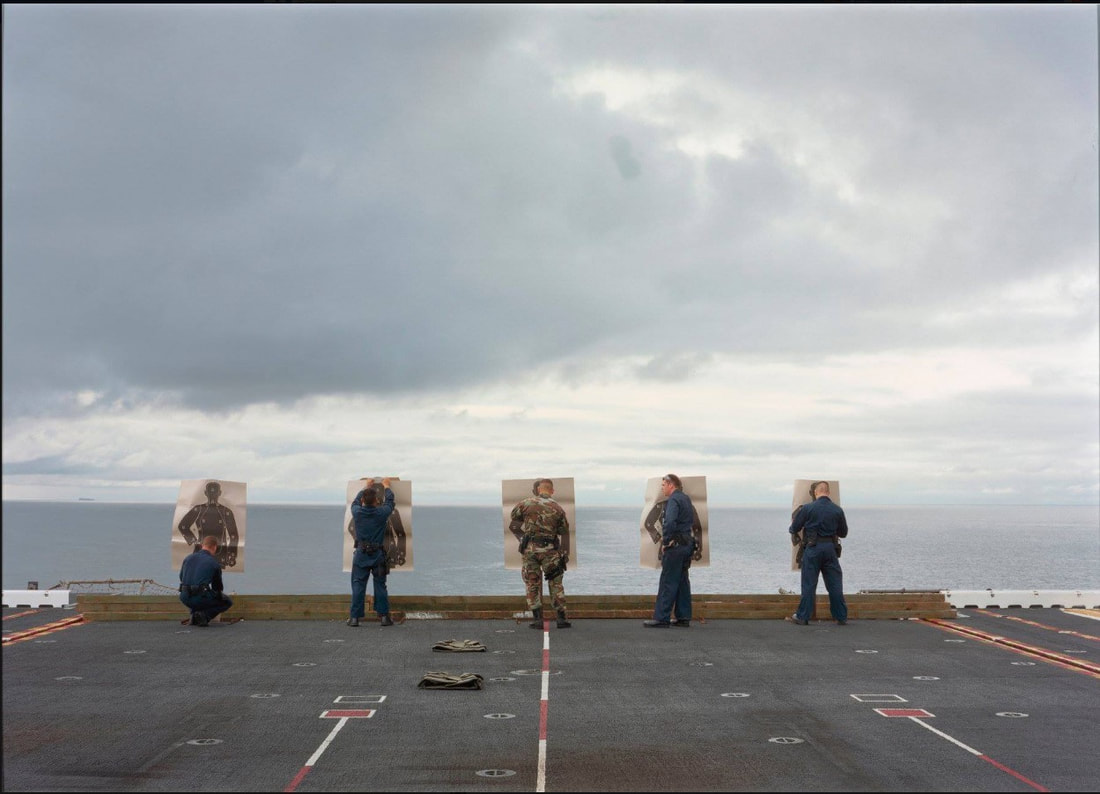

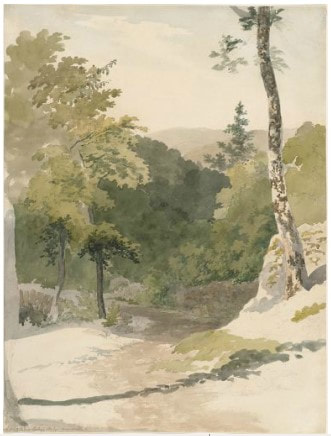

The proliferation of watercolor landscapes in England in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was due in no small part to the introduction of those premixed watercolor paints. Artists began to experiment with the medium and test the boundaries of what could be accomplished. Soon these works found their way into the annual exhibitions of the English Royal Academy, but they were so marginalized that a group of artists split from the Academy in 1804 to establish the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. The goal of this new Society was to place watercolors on an equal footing with oil paintings, and artists responded by creating large-scale, highly finished watercolors displayed in elaborate gold frames. The Baltimore Museum of Art is fortunate to have an example of one of these presentation watercolors by Britain’s favorite son, Joseph Mallord William Turner. In contrast to the highly finished exhibition watercolors, many artists created more intimate works in the same medium. Artists went outdoors with sketchbooks and paints to test their skills at portraying the landscape. One such work from a sketchbook (notice the crease down the center) is a favorite acquisition. The artist is John White Abbott, a country surgeon and apothecary from Exeter, who as an amateur artist painted for his own enjoyment (the term amateur indicates only that the artist did not earn money making art, but is no indication of a lack of talent). After inheriting an estate from his uncle, he was able to devote himself full time to painting. Abbott probably drew A Path through the Woods first in graphite pencil on the spot, and then returned to his studio to finish the work with gray washes and pen and brown ink. I continue to be amazed at the quality of light through the dappled foliage painted with just gray and brown. In fact, the execution is so masterful that I see this monochromatic scene in full color. In addition, the peacefulness of the scene always transports me to somewhere else. For me, this work is a figurative and literal breath of fresh air. John White Abbott (English, 1763‑1851) A Path through the Woods, c. 1785‑1795. Pen and brown and gray ink with brush and gray ink over graphite Sheet: 256 x 335 mm. (10 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Rhoda Oakley, Baltimore, BMA 2008.9 Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, 1775‑1851) Grenoble Bridge, c. 1824. Transparent and opaque watercolor with scraping over traces of graphite Sheet: 530 x 718 mm. (20 7/8 x 28 1/4 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased with exchange funds from Nelson and Juanita Greif Gutman Collection, BMA 1968.28 Ann ShaferFile this one under it's not always about prints and printmaking. In the fall/winter of 2013-14, the BMA showed the work of photographer An-My Lê (pronounced Ann-Mee Lay). It was an honor to work with her and, as often happens, the museum acquired one of the photographs from the show. When it came time to select objects to talk about on video for the BMA Voices initiative, this one was a no-brainer. It's got it all. Here's the link to the short video we made: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fuT0JHVXmE. In the brochure for the exhibition, I concluded in this manner: In their quiet, unassuming way, Lê's sublime landscapes remind us that war is complex and contradictory. Alongside the brutality of combat, there is also the thrill of danger and adventure. Where there is enormous loss, there is also honor. Where there is heated protest, there is also heartfelt patriotism. By calling attention to the global reach of the U.S. military, Lê's photographs point out how martial power is balanced by humanitarian assistance and support of scientific research. Any discussion of the military will be polarizing, but Lê is able to find equilibrium between opposing points of view. While her photographs appeal to conservatives who see her work as pro-military, they also speak to liberals who read her work as anti-war. In drawing back the curtain to reveal the inner workings of the military as a giant facet of the global economy, Lê's photographs encourage us to think about its many complexities. An-My Lê (American, born Vietnam, 1960) Target Practice, USS Peleliu, 2005 Inkjet print, pigment-based Sheet: 1016 x 1435 mm. (40 x 56 1/2 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2014.5 Ann ShaferFile this post under nothing lasts forever, even on the interwebs. For the BMA's 100th birthday, staff produced 100 blog entries on favorite collection objects. Some were videotaped pieces featuring curators, conservators, and other staff speaking on camera; other entries were written posts. I went to look for my written pieces on artbma.org and couldn't find them anywhere (thankfully, the videos are still on YouTube). Thanks to Laura Albans, I have recovered the text for my entry on Dürer's Knight Death and the Devil, portions of which I share here.

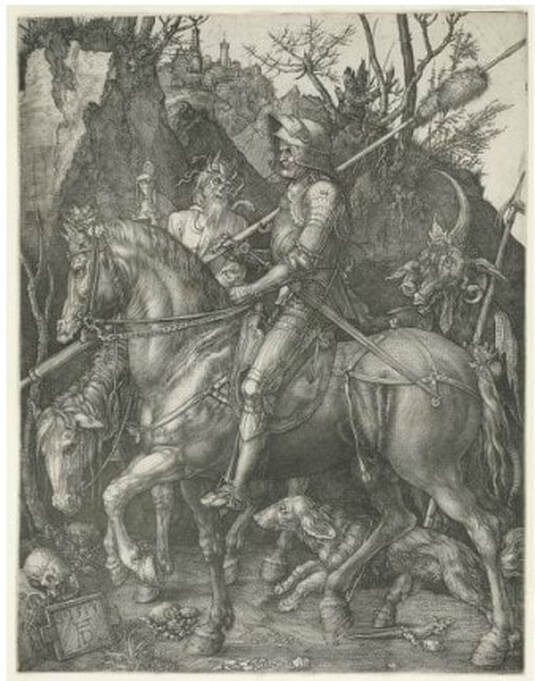

The best part of working in a large collection of prints, drawings, and photographs is the range of material. I used to always say that you could come up with almost any theme and find an entire exhibition on it drawn out of the solander boxes. Since my interests tend toward the 20th and 21st centuries, it may surprise some of you, then, that Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil is one of my favorite prints of all time. Not only is it a glorious example of engraving, but also it carries a universal message to stand by the courage of your convictions. Albrecht Dürer was a German printmaker, draftsman, painter, observer of nature, and humanist. In 1513 and 1514 he created a trio of engravings that have come to be called his master prints. In addition to Knight, Death and the Devil, the trio includes St. Jerome in His Study and Melencolia I. Most scholars agree that the former represents the active life, while the two others represent the intellectual life and the contemplative life respectively. While the three prints together are spectacular, I’m most drawn to Knight, Death and the Devil. The image is a visual feast. It features a righteous German knight resplendent in armor, a horse straight out of Renaissance Italy, a wonderful and faithful companion Fido the dog, and gnarly creatures representing Death and the Devil, all set in a naturalistic landscape. Contemporaries of Dürer would have understood the symbolism of every aspect of this print. But our own unfamiliarity with those symbols doesn’t lessen the impact of the work. Clearly this stalwart fellow is making his way through the forest of temptation and vanitas. He is able to keep to his path, ignoring all that is going on around him and stands by the courage of his convictions. Even if we strip the image of its religious associations of pre-reformation Catholicism, the message of perseverance is clear. Stick to your guns, well, lance, and you can get through anything with grace and dignity. A message as important today as ever. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528) Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513 Engraving Sheet (trimmed within platemark): 244 x 187 mm. (9 5/8 x 7 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Alfred R. and Henry G. Riggs, in Memory of General Lawrason Riggs, BMA 1943.32.188 This image is less than stellar, serving as an excellent reminder that it's always better to see works like this in person. Ann ShaferSometimes you get lucky and come across an artist by chance whose work you love. Even better is when you become friends. I made a studio visit to an artist who happened to be married to Susan Harbage Page. Because their studios were adjacent, I was able to see both in one visit. Susan's work runs the gamut: photography, drawing, performance, fibers, writing. One project has always risen to the top for me. The Border Project is a long running exploration of immigration issues focused on the border at the Rio Grande river in Brownsville, Texas. (An exhibition catalogue about the project is available here: https://susanharbagepagedotcom.files.wordpress.com/…/1_bord….)

Long before children were being separated from their parents, Susan spent a lot of time photographing objects in situ and then collecting them. The objects left behind by migrants--bras, wallets, identification cards, shirts, toothbrushes--are catalogued and photographed in an anti-archive. The large-scale, color photographs of objects in the landscape hold power for me. Yet, sometimes no object is needed as evidence of a human presence. In Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, a human-sized divot in the dry, tall grasses has been recently used as a resting or hiding place after crossing the border from Mexico. Easy to miss, once we understand how these crossings occur, we will recognize signs like this one forever. This now-empty nest is simple, stark, potent, and full of untold stories both of hope for a better life and fear of capture. Susan Harbage Page (American, born 1959) Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, 2011, printed 2012 Inkjet print, pigment–based Sheet: 1067 × 1553 mm. (42 × 61 1/8 in.) Image: 965 × 1448 mm. (38 × 57 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of the Artist, BMA 2012.156 Ann ShaferYou might be surprised to learn that Hayter's workshop is still operating in Paris at 10, rue Didot. After his death in 1988, the workshop changed its name to Atelier Contrepoint and is run by Hector Saunier, who printed many of Hayter’s late compositions. I was fortunate to be able to visit the Atelier twice, in 2014 and 2015. The first time was to meet Hector and see what the operation looked like. The second time Hayter's widow, Désirée, agreed to bring over one of his plates so Hector could ink and print it for us (there is no one better suited for this particular task). The plan was to create an online feature for the exhibition’s web site, which never happened because the show was cancelled. As usual, Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig were with me, and between the three of us, we shot a lot of video and photographed Hector and Shu-lin Chen printing Hayter’s Torso, 1986.

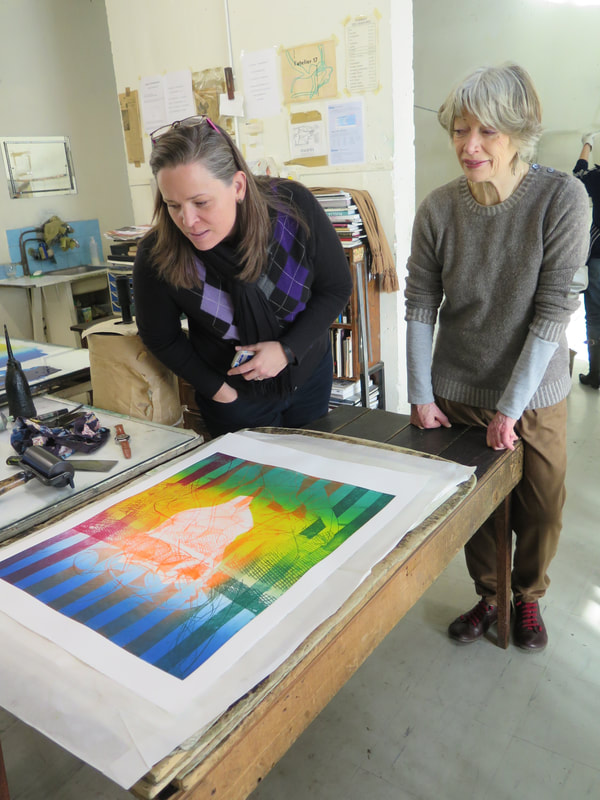

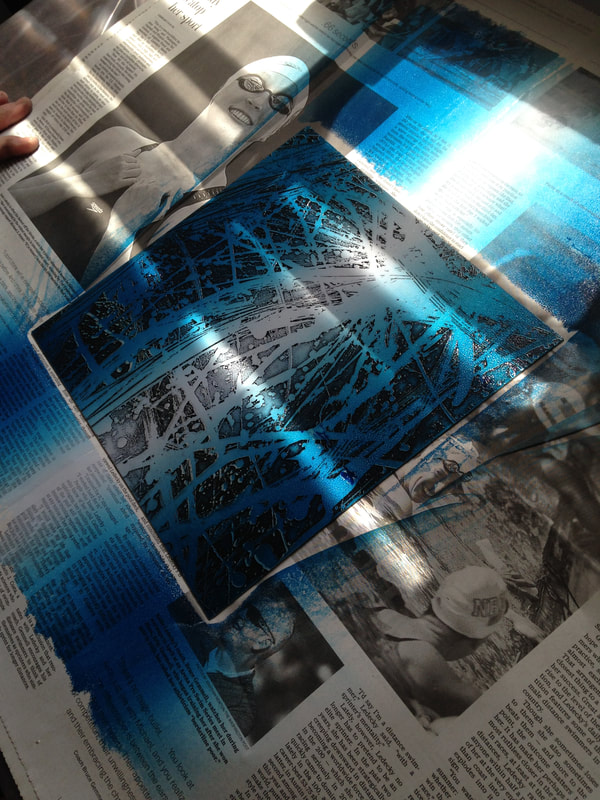

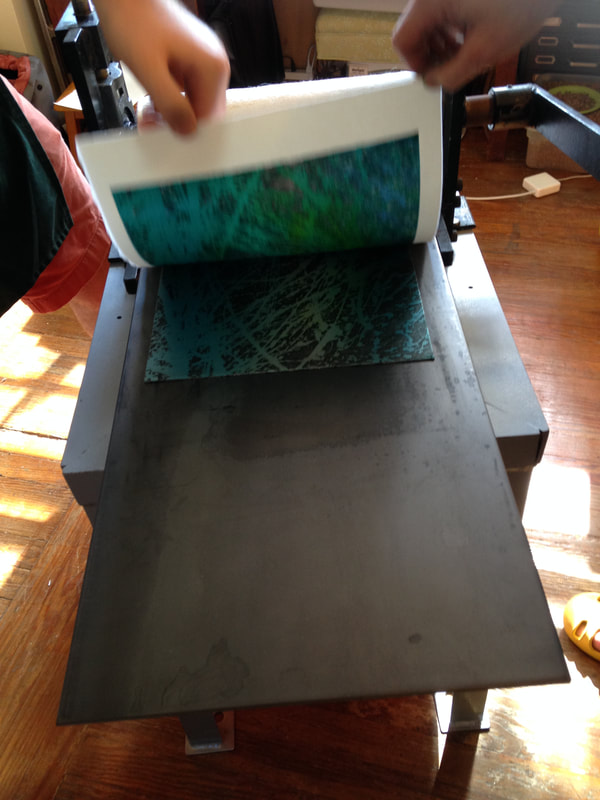

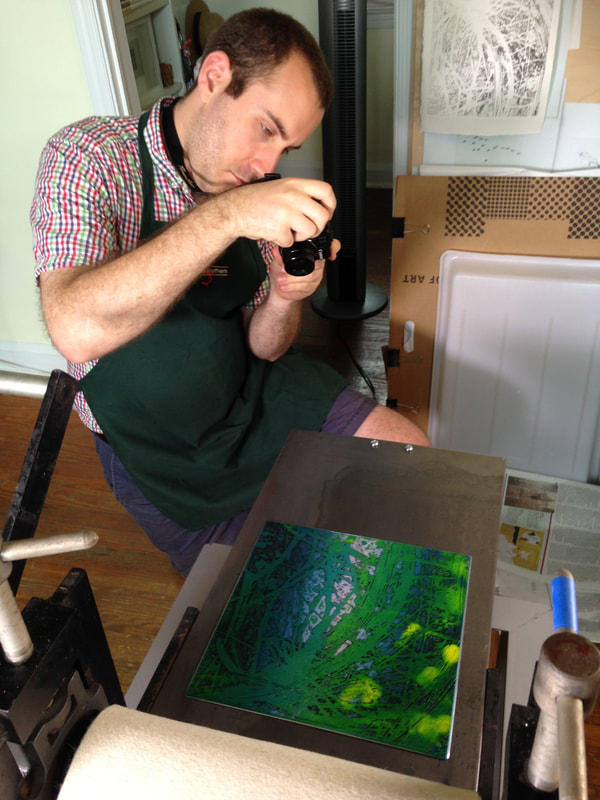

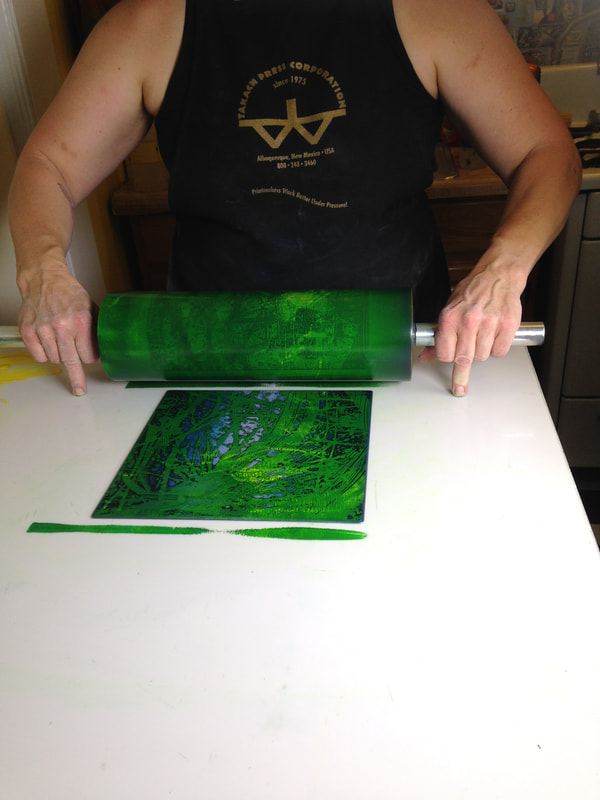

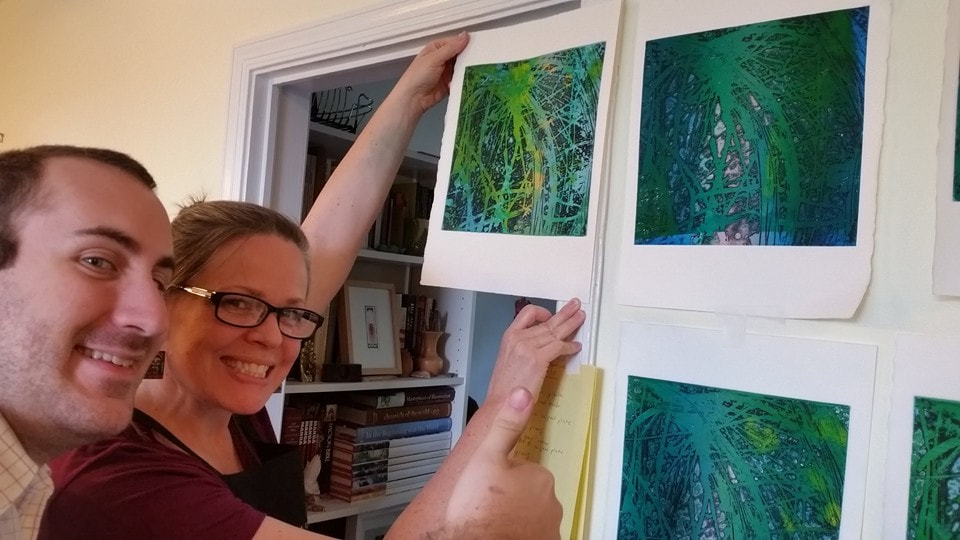

Désirée couldn’t find the plate she was originally thinking of, so she randomly selected Torso, which turned out to be serendipitous because Torso conceptually circles back around to the fist clenching the void discussed in an earlier post. In Torso, Hayter used stripes with inverted color variants, inking the central intaglio composition in green, red, and fluorescent orange, and with a horizontally rolled gradient of blue/yellow/green. The shape of the torso is defined by a mask that was laid down on the inked plate, blocking the rollers from depositing the blue, yellow, and green ink on the paper, producing an area of white across the center. The positive shape of the torso, described by an absence, echoes the conundrum of the untitled plate six from The Apocalypse, in which the negative space of a clenched fist is described by a positive volume. In this late print, the cognitive inquiries and accumulated techniques of four decades have come together. With the copper plate under her arm, we met Désirée on the appointed day at Atelier Contrepoint. After consulting the catalogue raisonné, they got right to work. Shu-lin set about inking the plate (intaglio) in red, fluorescent orange, and dark green in vertical stripes. Hector prepared the rainbow roll of blue, yellow, and green on a glass palette. The mask was still wrapped with the plate, so it was used as well. When Shu-lin was satisfied with her wiping job, the plate was ready for the mask’s placement and the rainbow roll. Hector completed his part and the plate was placed on the bed of the press that had been used for thousands of prints by hundreds of artists over the majority of the twentieth century. After a few unsatisfactory pulls, they printed four impressions, one of which eventually entered the Baltimore Museum of Art’s collection. I remain amazed that I got to experience the printing of one of Hayter’s plates and so appreciative of Désirée, Hector, and Shu-lin’s generosity that day. Even better, Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig were with me to witness the magic. Ann ShaferIn my previous post I talked about Stanley William Hayter's 1959 open bite etching Cascade and promised to dig into its making. It takes many images to describe the process of simultaneous color printing, so I created a PDF slide deck to illustrate how Ben Levy, Tru Ludwig, and I made a group of test prints to figure it all out. You can find the PDF here:

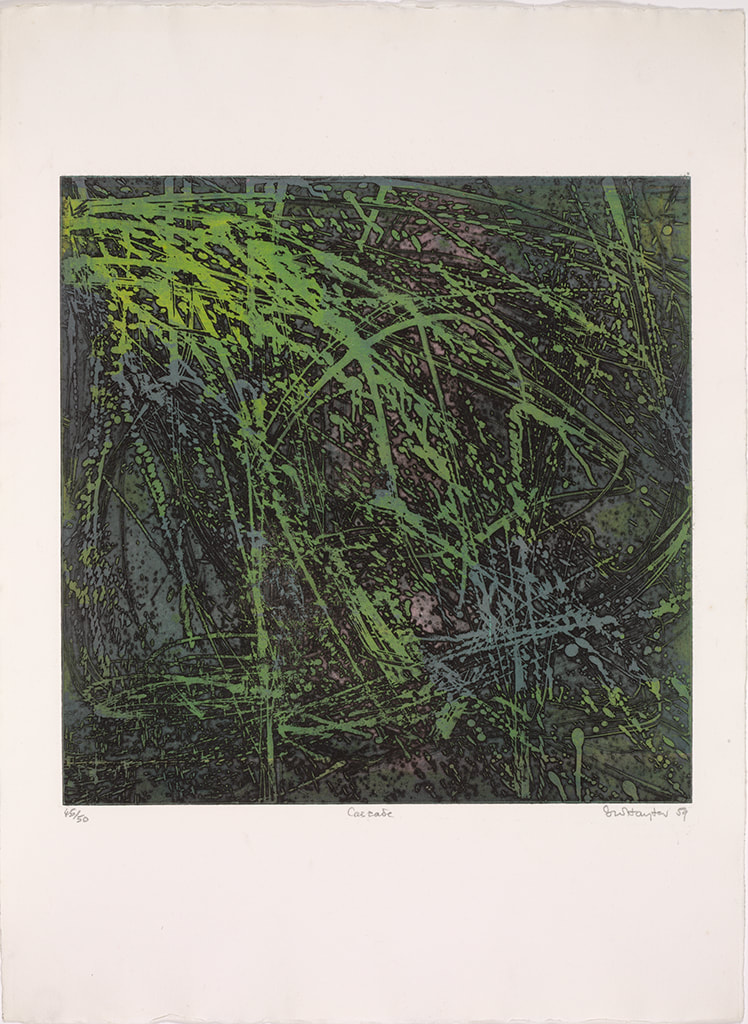

Ann ShaferCascade, 1959, by Stanley William Hayter, is the print I planned to use of the cover of the catalogue. One, because it's gorgeous. Two, because by 1959, Hayter is 58 and had been at it for more than thirty years and Cascade sums up so much of Hayter's thinking. During that time, he's helped Spanish refugees during the Spanish Civil War by hiding them in the studio; he's dropped everything and fled Paris as it went to war with Germany in 1939; he's created something really special in NY during the war and following (he's in NY from 1940-1950); he's watching his 16-year-old son die in 1946; he's helped hundreds of artists find their voices and discover new ways of creating intaglio prints; he, like so many other artists, has grappled with the horrors revealed by the Holocaust and bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and he's been able to return to France and purchase a vacation home in the south of France. But Hayter was also a man who never stopped thinking, working, creating, loving, living. Three, it's a great place to start talking about one of the Atelier's most important discoveries, that of simultaneous color printing (sometimes called viscosity printing, although Hayter didn't like that term since all inks have a viscosity of some sort).

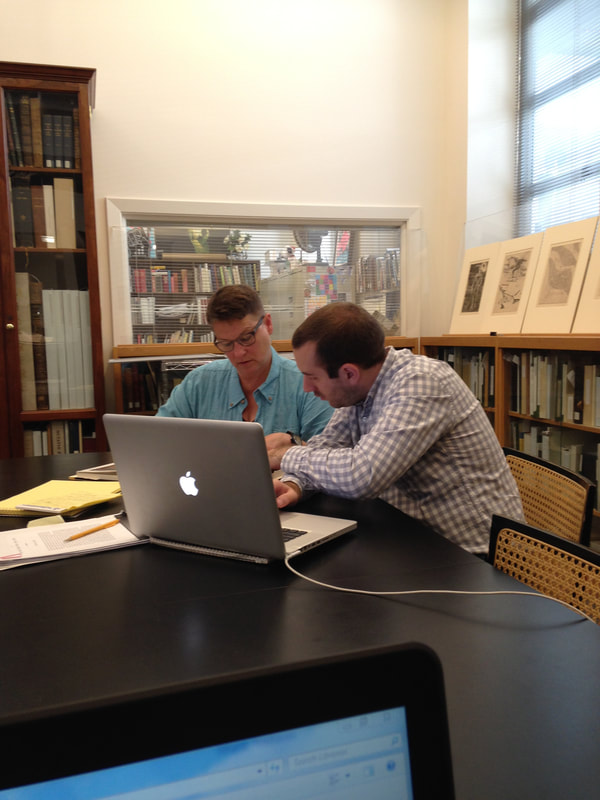

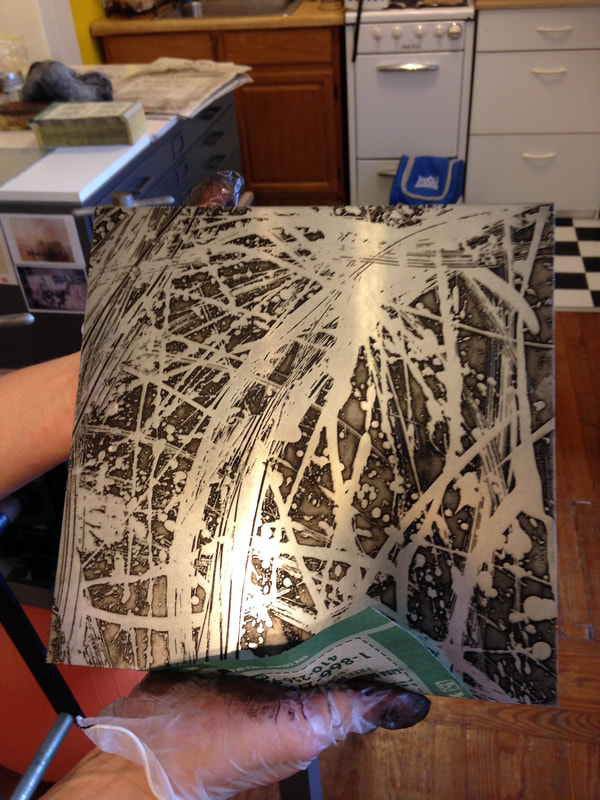

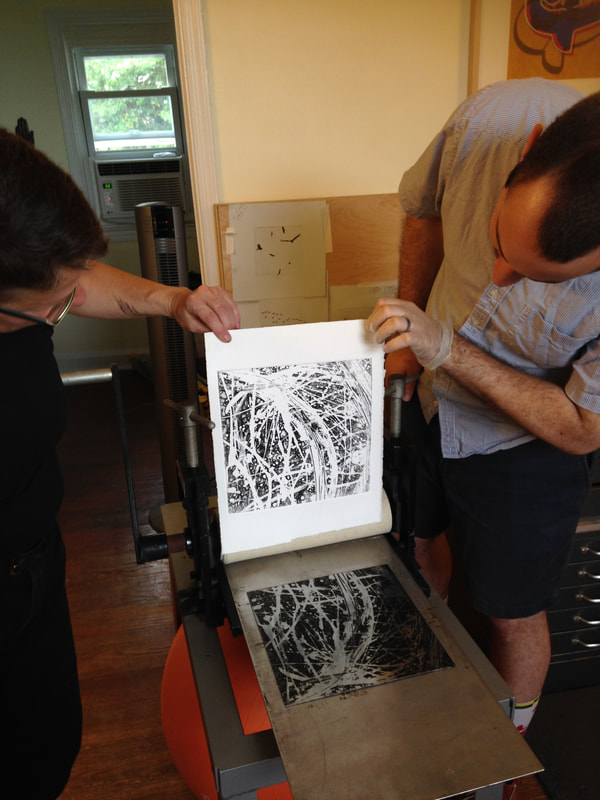

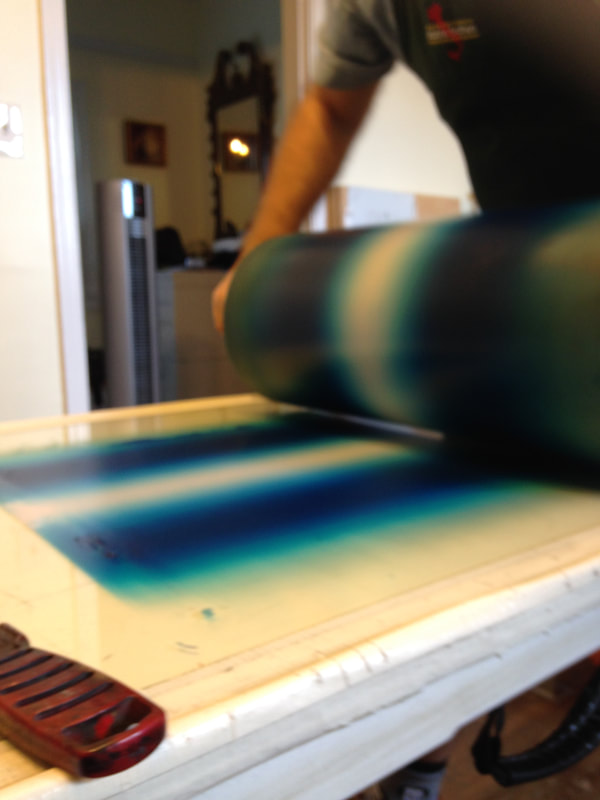

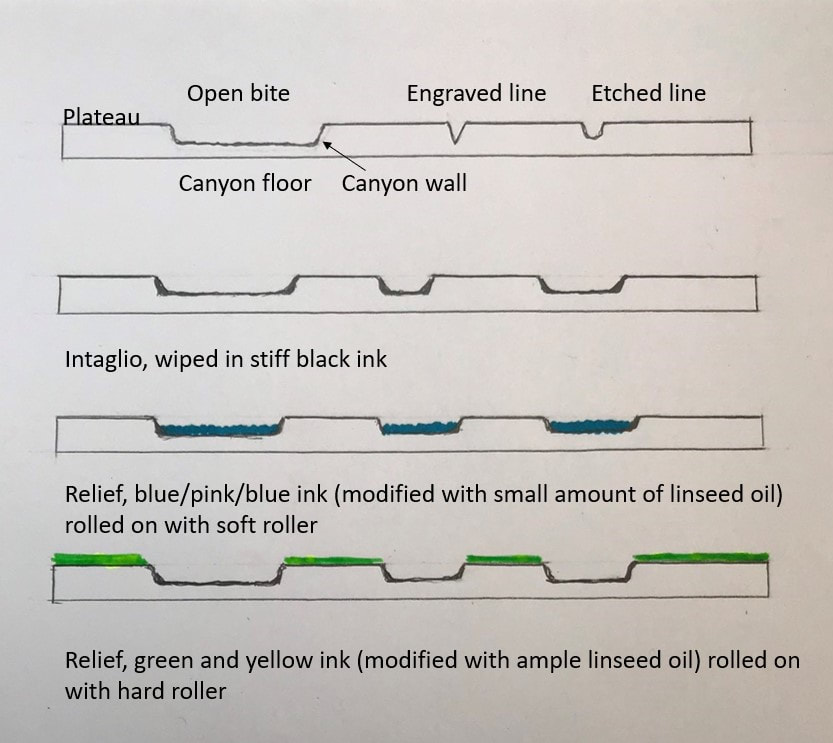

Cascade, 1959, is a colorful print with an all-over composition that appears completely abstract; seemingly random drips and gestures cover the plate. Hayter, however, never accepted pure abstraction as a meaningful subject—even when his subjects defy conventional representation, his titles anchor them in the world of places and things. Cascade is one of many works inspired by the appearance of rushing water in a river near his home in the south of France. The direct autographic drawing that had been essential to Hayter’s work since he began engraving has disappeared, replaced by a variety of devices that could be set in motion by his hand, but whose outcomes were far more open to chance: leaking cans of liquid ground suspended as pendulums, and marker pens that could dribble and spray showers of thin resist. These systems recorded, rather than depicted, the behavior of liquids in motion. Cascade is an indexical print (see prior post about Trisha Brown). Despite all of the scholarly reasons we can cite for Hayter's switch from engraving lines to depict images to indexical splashes of liquid, I've always wondered if his hands were just tired and he was dealing with an onset of arthritis. I have absolutely no proof of this--it's just a thought. What's so intriguing to me about the print is figuring out how in the world a bunch of open-bit swooshes and gestures are inked to produce the colorful image. First, we need to understand that to produce a color print, normally one would create separate copper plates for each color and they would be printed in successive layers on the paper in multiple passes through the press. Instead, Hayter layered the different colors on the same, single plate, and ran it through the press once. The trick is to vary the amount of oil in each color so that they don't run together as they are applied. (This idea was developed at the Atelier by Krishna Reddy and Kaiko Moti--an example of the collaborative nature of the workshop.) Along with the print itself, I'm including an image of the zinc plate (also in Baltimore's collection, a gift from Mrs. Hayter, BMA 2014.40), and an image that shows the cross section of the plate in the order it is inked. I hope this will make some sense; we'll dig in more tomorrow. First, the plate is wiped intaglio in black so that the ink clings to the canyon walls; second, a soft roller carrying the rainbow roll of blue/pink/blue deposits color in the canyons; third, a hard roller deposits an unblended green and yellow across the plateau. This will all be made clearer tomorrow when I share the test plates we created for the exhibition to show each step in this inking process. Because these test plates are the first and only etchings I've ever made, you can imagine I had help. I am deeply, supremely indebted to Tru Ludwig and Ben Levy, who made it all happen. Tomorrow you'll see us in action. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Cascade, 1959 Open bite etching; printed in black (intaglio), blue-pink-blue gradient (relief), yellow, green, and blue, unblended (relief) Sheet: 794 x 584 mm. (31 1/4 x 23 in.) Plate: 489 x 489 mm. (19 1/4 x 19 1/4 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, BMA 2008.112 Ann ShaferIn the previous post I shared a video about Stanley William Hayter (known as Bill to his friends), an artist that has interested me for many years. I also shared a link to a PDF catalogue for an exhibition that took place last year in São Paolo, Brazil. I was lucky enough to participate in a conference there in conjunction with that exhibition, Atelier 17 and Modern Printmaking in the Americas. I’m sharing a summary of the conference I wrote for another publication that I hope you find interesting. And, if you or any of your students need a dissertation topic, read through to the end. The conference was held at the Museu de Arte Contemporãnea, which is part of the University of São Paolo and is known as MAC USP. Both the exhibition and conference focused on printmaking and artistic exchange between the United States and South American countries in the mid-twentieth century. The exhibition, catalogue, and conference were born out of the research of USP graduate student Carolina Rossetti de Toledo, who, under the supervision of professor and chief curator Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, focused on several gifts to São Paolo’s new Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in the 1950s of prints from Nelson Rockefeller, Henry Ford, and Lessing Rosenwald (the majority of MAM’s permanent collection was transferred to MAC USP upon its founding in 1963). Nelson Rockefeller made two gifts, one in 1946 of paintings and sculpture and another in 1951 of twenty-five modern prints, to assist in the establishment of a museum of modern art in São Paolo. (He also donated a group of paintings to a museum in Rio de Janeiro in 1952.) Rockefeller’s interest in Brazil began when he travelled there as the director of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, the purpose of which was to strengthen relations with Latin America during World War II, both politically and culturally. The initial selection of prints for the Rockefeller donation was made by MoMA curator William Lieberman, who chose prints that represented cutting-edge modernism. The majority reflect American printmaking of the time, meaning works by artists associated with Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. Why Rockefeller focused on MAM in São Paolo specifically remains unclear. Whatever the real reason, it was noted as a “gesture of goodwill.” A selection of prints from the 1951 gift were exhibited that year in São Paolo but have rarely been shown in the intervening years. Following Rockefeller’s gesture, Henry Ford donated one print in 1953, and Lessing Rosenwald made a gift of nine modern prints in 1956, which were meant to augment the collection in the area of international modernism. The connection between the three donors and what motivated the Ford and Rosenwald gifts is unclear. But among the prints in these later gifts were yet more examples of international modernism in the form of works by artists associated with Atelier 17. For Brazilian artists, there were three possible points of contact with Atelier 17. The first was through trips abroad. The second was through the publication and circulation of books by Hayter and his associates. The third was through exhibitions such as MoMA’s 1944 Atelier 17 exhibition, which traveled not only around the United States but also throughout Latin America, and through the exhibitions of works by Atelier 17 artists in the São Paolo Biennials and other venues. Hayter had an exhibition in Rio de Janeiro in 1957, which also traveled to Buenos Aires, and his work was included in the British pavilion in the 1959 São Paolo Biennial (MAM purchased several prints from this show). Interestingly, Atelier 17 artist Minna Citron had an extensive one-person show at MAM in São Paolo in 1952, which was by far the biggest exposure of an Atelier 17 artist in Brazil up to that point. Citron was fairly proficient in Portuguese (and many other languages), which may account for how she secured and coordinated this show. Several of the prints in the Rockefeller gift to MAM had been shown in other impressions in the 1944 MoMA exhibition and yet other prints in the gift were seen in Una Johnson’s seminal National Print Annual exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum. In other words, the gift was of cutting-edge contemporary prints. There are still gaps in the story, however. In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, Rossetti de Toledo notes, rightly, that the connections between modern American and European printmaking and its Latin American counterparts are not well understood or properly documented. The Rockefeller gift is one piece of the puzzle. Rossetti de Toledo’s research into the Rockefeller gift developed into the MAC USP exhibition and bilingual catalogue, both majorly supported by the Terra Foundation. In addition to prints from MAC USP’s collection, the exhibition featured loans from the Terra Foundation’s extensive collection of American prints and works from the Brooklyn Museum and Art Institute of Chicago. The conference began with introductory remarks from Magalhães and Terra Foundation curator Peter John (PJ) Brownlee. Rossetti de Toledo spoke about her research on the Rockefeller gift. I introduced Hayter and the Atelier 17, setting the stage for the discussion. Other speakers included Luiz Claudio Mubarac, who gave an overview of Brazilian printmaking in the twentieth century; Silvia Dolinko, who gave an overview of printmaking in her home country of Argentina; Heloisa Espada, who focused on Brazilian artist Geraldo de Barros (he worked at Atelier 17 in Paris in 1951); and Priscila Sacchettin, who spoke about Livio Abramo (he worked at Atelier 17 in 1951–52 and his work appears in Hayter’s book, About Prints). Christina Weyl closed out the conference with her talk on women at Atelier 17, which was an excellent preview of her important, recently published book. Over the course of two days, it became clear that South American printmaking runs in sometimes intersecting but separate tracks from European and American art. While artists cross pollinated through travel, books, and exhibitions, for those of us who study prints, there’s a whole other world of printmakers to be discovered in South America. It is also clear that research on these printmakers is wide open. Brazil lacks the central repository of artists’ papers and archives like our Archives of American Art. Many of the artists’ families remain in possession of the works and papers of their creative relatives. These artists’ estates have not been formalized or catalogued, nor are they easily accessible. Hardly any estates’ papers have found their way into libraries or universities, meaning there is a lot of room for intrepid scholars to uncover the careers of any number of artists. How’s your Portuguese? Need a dissertation topic? As I noted yesterday, the exhibition catalogue was printed in a small run but a pdf of the book is available here: bit.ly/Atelier17MACUSP. I also include a list of Brazilian and Argentine artists who were mentioned repeatedly. Brazilian artist-printmakers of note: Edith Behring (1916–1996) Maria Bonomi (born 1935, she was married to Abramo) Ibêre Carmargo (1941–1994) Oswaldo Goeldi (1895–1961) Marcelo Grassmann (1925–2013) Evandro Carlos Jardim (born 1935) Renina Katz (born 1925) Anna Letycia (born 1929) Maria Martins (1894–1993) Fayga Ostrower (1920–2001) Carlos Oswald (1882–1971) Mário Pedrosa (1900–1981) Gilvan Samico (1928–2013) Lasar Segall (1891–1957) Regina Silveira (born 1939) Argentine artists-printmakers: Hilda Ainscough (born 1900) Mauricio Lasansky (1914–2012) Julio LeParc (born 1928) Fernando López Anaya (1903–1987) Ana Maria Moncalvo (1921–2009) At the exhibition reception: (L-R) Taylor Poulin, Elizabeth Glassman, Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, Peter (PJ) Brownlee, Christina Weyl, Amy Zinck, and Ann Shafer. Photo by MAC USP staff.

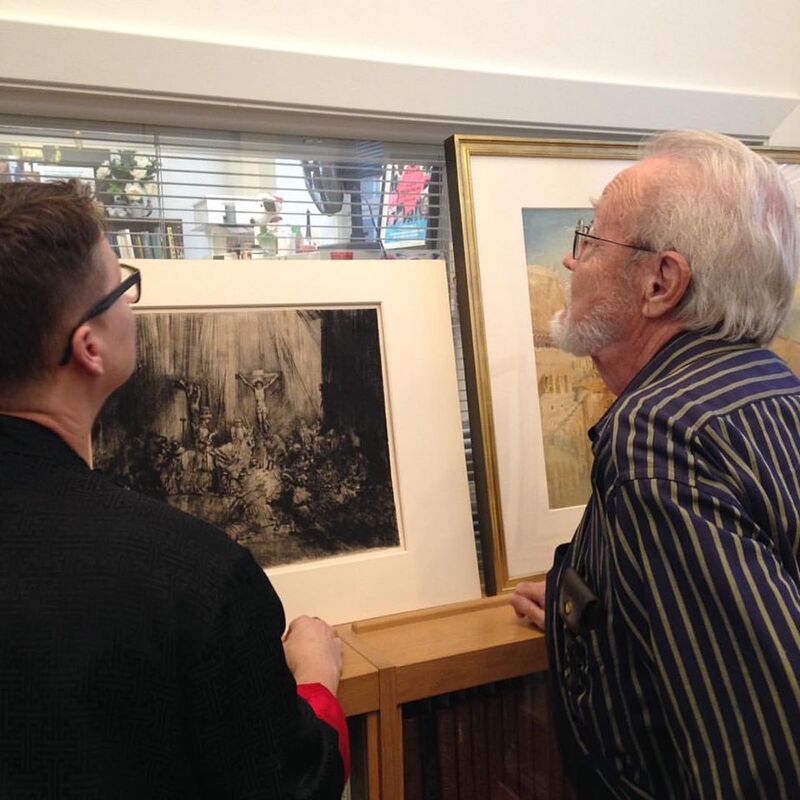

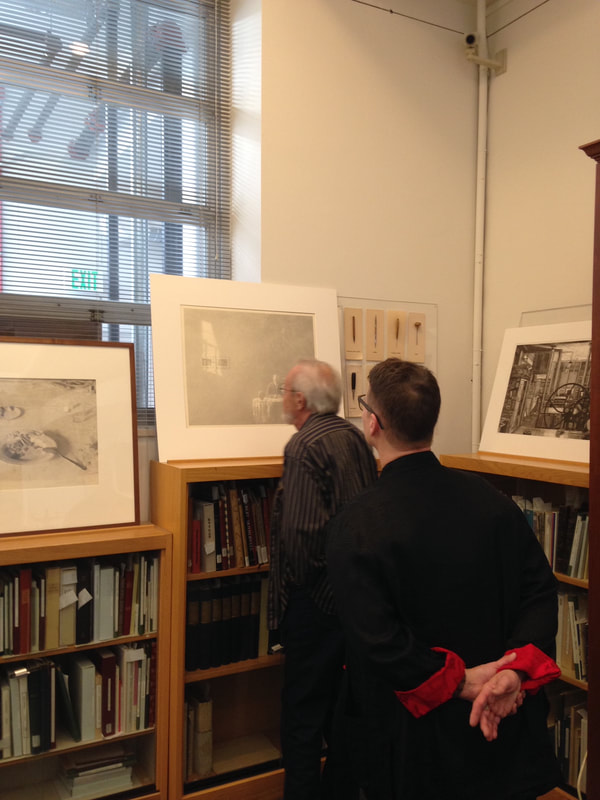

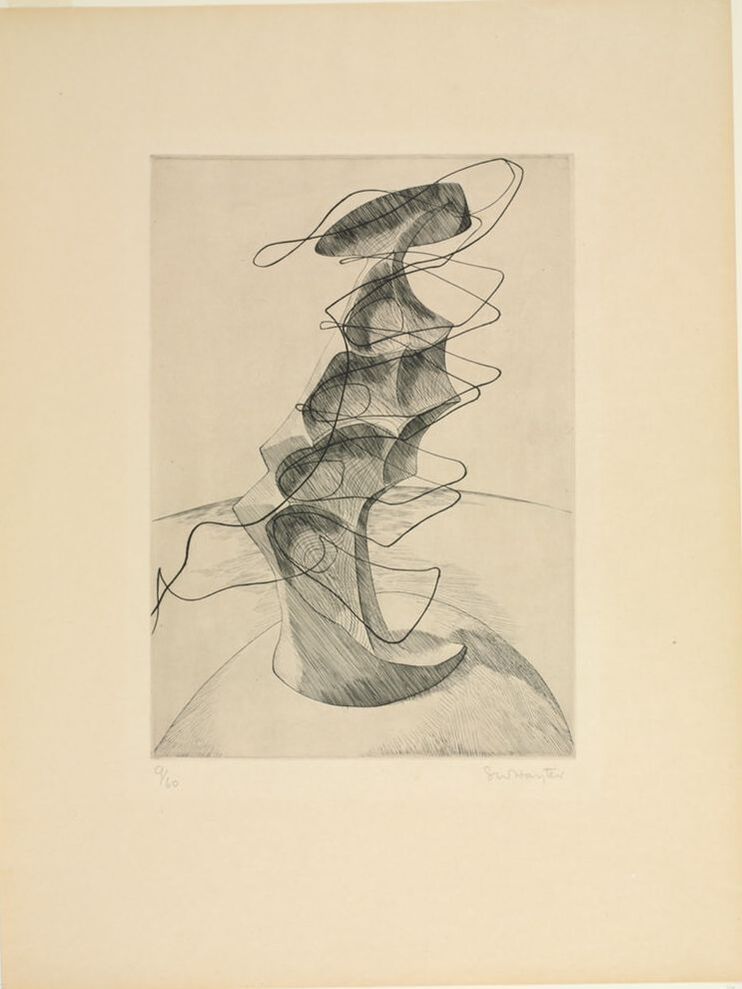

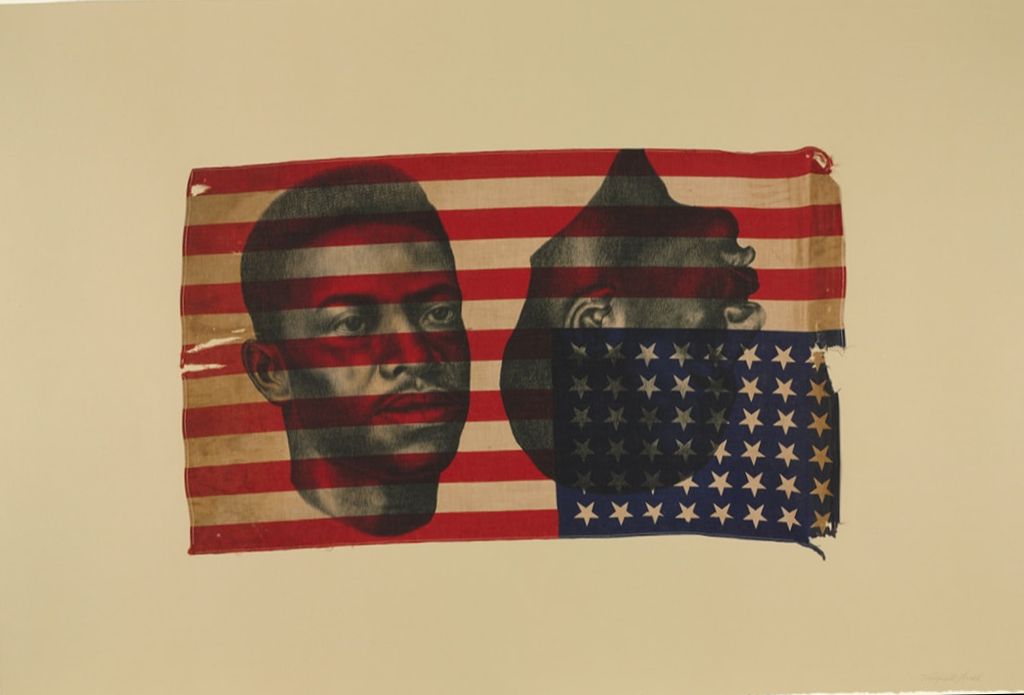

Ann ShaferIf you know me at all, you know I spent a very long time working on a project focused on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17. I always talked about him as a lightning rod around whom bazillions of artists swirled. I believe his and the atelier's story is the fastest route to inserting printmaking firmly into the now-ever-changing canon. My attempt to do that in a grand fashion was not to be through circumstances out of my control, but a few smaller projects resulted. Some of the research is published in a catalogue for an exhibition at MAC USP (University of Sao Paolo). The print run was quite small, but the catalogue PDF is available here: bit.ly/Atelier17MACUSP. In addition, I was filmed talking about one of my favorite Hayter prints for the BMA, which is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJ6Z-8Yq9cs. I love this print. I feel like it sums up so much of Hayter's thinking and is among my top candidates for most important print of the 20th century. Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901-1988) Untitled (no. 6 from The Apocalypse), 1931 Engraving and drypoint; printed in black (intaglio) Sheet: 526 x 399 mm. (20 11/16 x 15 11/16 in.) Plate: 324 x 228 mm. (12 3/4 x 9 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Paul Mann, Towson, Maryland, BMA 1979.377.6 Ann ShaferI prefer looking at art with people. It slows me down and helps me engage more fully. I am lucky to have two partners in looking: Ben Levy and Tru Ludwig. (More on each of them in a later post.) During the 2011 NY Print Week, Tru and I headed downtown to hit the galleries. We were traipsing around Chelsea catching shows both on purpose and by chance when we tripped over this glorious print by Whitfield Lovell. There's always great stuff in 535 W 22nd St., home to DC Moore Gallery, Leslie Tonkonow, and Julie Saul. DC Moore had a show up of Lovell's fabulous drawings, one of which I would have loved to acquire--they were out of range for the museum's budget. There turned out to be some treasures not on view, too. (At print fairs, the best stuff is often under the table--always ask to see it.)

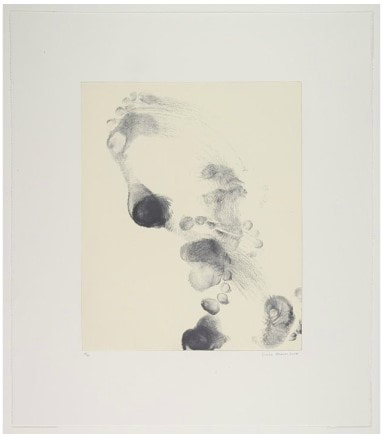

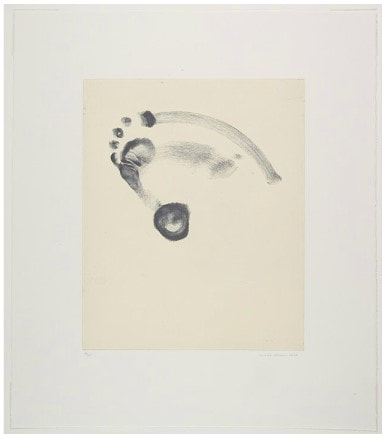

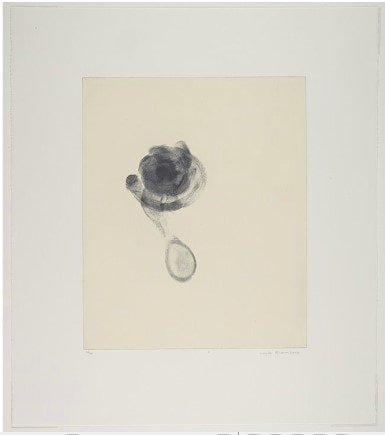

Lovell's lithograph, Deuce, was published by Smith College in an edition of 40 on Ivory Plike paper, but several experimental versions had been printed on vintage flags, which, to my mind heightens just about everything about the print. One of these special versions had the flag in a vertical position, which made the disembodied heads look like they were hanging/lynched. Now, I'm not one to shy away from a strong, political work of art, but I believe the one we acquired held more impact in its ambiguity: the red stripe across the mouth effectively silencing the man, the clarity of his eyes as he sees all of the inequities and injustices around him, the ambiguous and complicated relationship African Americans have with patriotism. There is so much to unpack here and it was frequently used in the studyroom for various classes. Someday I would love to mount a Lovell exhibition. He's worth checking out. Whitfield Lovell (American, born 1959) Published by Smith College Print Workshop Printed by Derrière L'Étoile Studios Deuce, 2011 Sheet: 768 x 1130 mm. (30 1/4 x 44 1/2 in.); Image: 413 x 705 mm. (16 1/4 x 27 3/4 in.) Crayon lithograph on American flag mounted to paper The Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2012.154 Ann ShaferThe first time I went to the IFPDA Print Fair at the Park Avenue Armory, I didn't know anyone, wasn't traveling with anyone, and felt overwhelmed. (Art fairs can do that to a person.) At the end of a very long day, I paused in the Graphicstudio booth where soon-to-be-friend Kristin Soderqvist invited me to sit down. We were chatting about nothing in particular when I glanced over her shoulder and saw these prints by choreographer Trisha Brown. These are softground etchings with a relief roll of yellow on the surface of the plate. To create the image, Brown pirouetted on the plates that were coated with a soft, sticky ground, allowing the impression of her foot to be recorded. These are the first works that helped me understand the concept of being indexical. Simply put, instead of drawing what a foot in action looks like, the image is the product of the thing itself in action. I also love the idea of a dancer's work transferring to the wall, especially since one of Brown's famous pieces featured a person walking down the side of a building (https://trishabrowncompany.org/…/man-walking-down-the-side-…). These were the first works I acquired from a fair for the BMA's collection.

Trisha Brown (American, 1936-2017) Published by Graphicstudio; printed by Tom Pruitt (American, born 1956) Untitled Set One, No. 1–3, 2006 Sheet (each): 657 x 578 mm. (25 7/8 x 22 3/4 in.) Plate (each): 429 x 352 mm. (16 7/8 x 13 7/8 in.) Set of three softground etchings printed in black (intaglio) and yellow (relief) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2007.336–338 Ann ShaferYou may not know that I have a secret passion for British watercolors of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The BMA has a glorious Turner presentation watercolor of Grenoble Bridge, but few companions. In 2008 I put together a small show featuring the Turner and was able to acquire this watercolor to augment the show and the collection. It's by Robert Hills, an artist best known as an animalier--one who specialized in painting animals. In this watercolor he captured the curve in the country road with the broken-down fence at left and singular tree at right. It's a crisp, lovely sheet--the whites are white and the colors strong--and it has all the features one wants in such a composition: a path leading the eye back in space, a framing tree and shadow, that broken down fence as a bit of nostalgia in industrializing Britain, the sense that it was painted on the spot (it likely was), and its uncontrolled picturesqueness. I think this was my first purchase for the collection. I love it still.

Robert Hills (English, 1769–1844) Nook End, Ambleside, c. 1807 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 357 x 270 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 5/8 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from Bequest of Saidie A. May, BMA 2006.93 Ann ShaferOne of my first acquisitions for the BMA was this Jim Dine print. I was working on a small show of his works from the collection and was able to purchase two of Jim's more recent prints to round out the show. The inimitable Tru Ludwig and I set off to NYC to shop at Pace Prints. I knew for sure I wanted to acquire A Side View in Florida, a massive skull derived from Grey's Anatomy, but was open about a second print. Then Raven on Lebanese Border was unveiled, and we knew instantly this was the obvious choice. It has been on view in multiple exhibitions and was my go-to in the classroom because of its Baltimore-related subject matter, experimental printing methods, and multiple techniques. It is probably the work that I got the most use out of. Jim Dine (American, born 1935) Published by Pace Editions, Inc., New York; printed by Julia D'Amario Raven on Lebanese Border, 2000 Sheet: 781 × 864 mm. (30 3/4 × 34 in.) Plate: 676 × 768 mm. (26 5/8 × 30 1/4 in.) Soft ground etching and woodcut with white paint (hand coloring) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, BMA 2007.224 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed