Ann ShaferEdward Hopper, the original social distancer. Seems like the perfect time to write about the first artist I studied in depth. Back in college, I was aiming at American paintings, mainly of the first half of the twentieth century. That I ended up a print person surprises me still since I backed into their study unintentionally. I wrote my junior thesis on Edward Hopper and his depiction of women in paintings. (Tip of the hat to my brother Ren MacNary, who helped me type it--on a typewriter.) I think I tried to approach it with a feminist lens but really, I was writing from my gut. I haven’t looked back at it in years; I don’t even know if I still have a copy, which is just as well. New York Movie, 1939, is one of my favorite Hopper paintings featuring a lone figure. I’m fascinated by artists’ depictions of the audience and the loneliness that can be felt in a room full of people. Hopper’s woman is a great example of the theme of alone in a crowd.

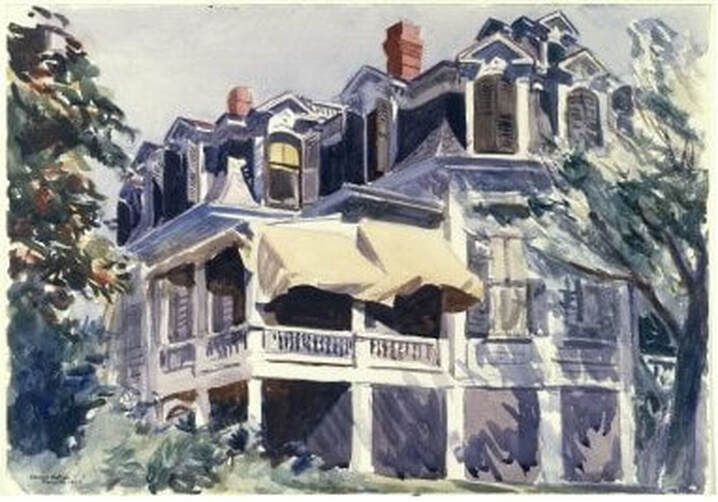

Like so many artists, Hopper also made work in other media as a regular part of his practice. I have a soft spot in my heart for good watercolors (I dabble, and my mother was pretty darn good at them) and Hopper painted some real beauties like The Mansard Roof, 1923. I love that he portrays Victorian domestic architecture (considered out of fashion at the time) rather than the picturesque harbor of the fishing village of Gloucester, Massachusetts, which was the focus of other artists working there in the twenties. Painted on an angle and from below, the house’s billowing yellow awnings dominate. While this is an accurate representation of the house, really it is an exercise in light and shadow. When he painted this house in 1923, Hopper was spending the first of six summers in Gloucester, was trying out watercolor for the first time, and had just met his soon-to-be-wife, Josephine Nivinson. In addition, after not selling any work for the prior ten years, this watercolor was included in an exhibition at, and subsequently purchased for the collection of, the Brooklyn Museum. Not bad for a first stab at the notoriously difficult medium of watercolor. His facility with the brush reminds me of another watercolorist who seemed to be able to whip off a gorgeous work in no time, John Singer Sargent. Because of my own experience and love of watercolors, landing a first job as a curator in a works on paper department represented a shift, but a good one. It wasn’t until much later that I made the final shift to loving prints, which are a tough sell to the public. The barriers to entry are many: the technical information is challenging and complicated, the concept of multiples is confusing, and what does “original” mean anyway. But, once we get people past a certain point, they’re in. Hence my self-identification as a print evangelist. My transition to the dark side was completed under the expert eye of Tru Ludwig. We’ve looked at thousands of prints together and he is my rock. Prior to painting in watercolor in Gloucester, Hopper began making etchings in 1915. He is said to have taught himself, but there is some thought that he learned some of the technical ins and outs from Martin Lewis (more on him in a future post). Of his seventy-some etchings (only 28 were published), my favorite is American Landscape, 1920. Formally, it is such an odd composition with its horizontality and the main subjects—a group of cows trundling over railroad tracks—occupying the lower half of the composition. Only the top of the house rises into the sky. Perhaps we could read into it that Hopper’s prevailing theme of loneliness is personified in the house that is cut off from society by the railroad tracks. Perhaps the cows are the farmer’s only link to the outside world. Who knows? But I do know that to our twenty-first century eyes, the composition looks like a film still: dramatic angle, stark lighting, mundane action portending the future. It all seems apropos in these times of pandemics, quarantines, and social distancing. Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) New York Movie, 1939 Oil on canvas 81.9 x 101.9 cm (32 1/4 x 40 1/8 in.) Museum of Modern Art, 396.1941 Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967) The Mansard Roof, 1923. Watercolor over graphite 352 x 508 mm. (13 7/8 x 20 in.) Brooklyn Museum: Museum Collection Fund, 23.100 Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) American Landscape, 1920 Etching Sheet: 326 x 442 mm. (12 13/16 x 17 3/8 in.) Plate: 185 x 313 mm. (7 5/16 x 12 5/16 in.) National Gallery of Art: Rosenwald Collection, 1949.5.70

0 Comments

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed