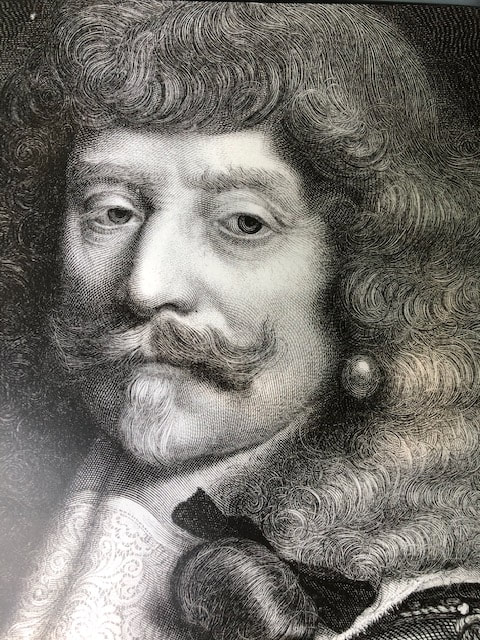

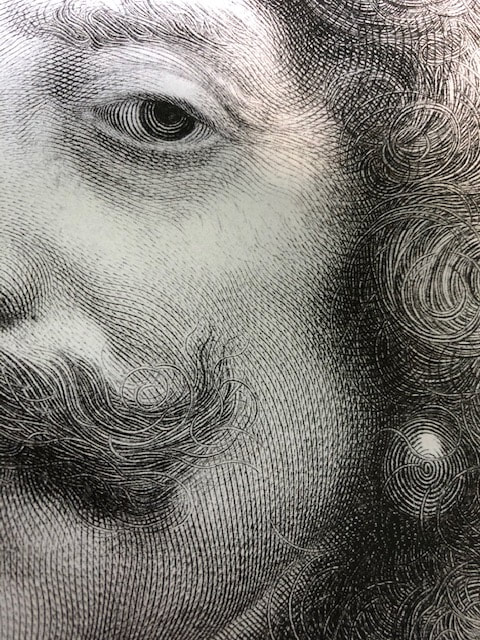

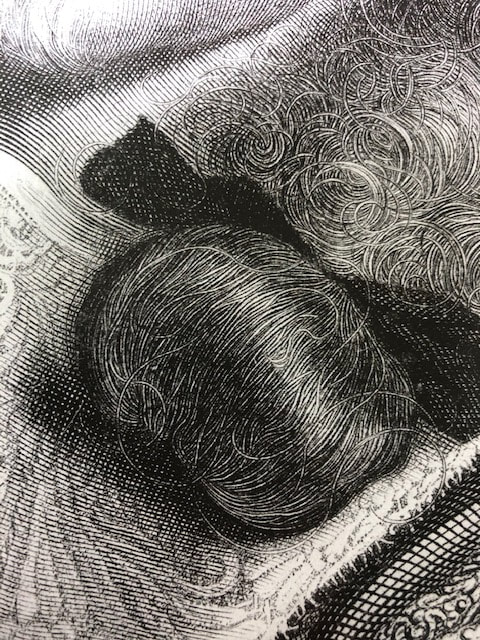

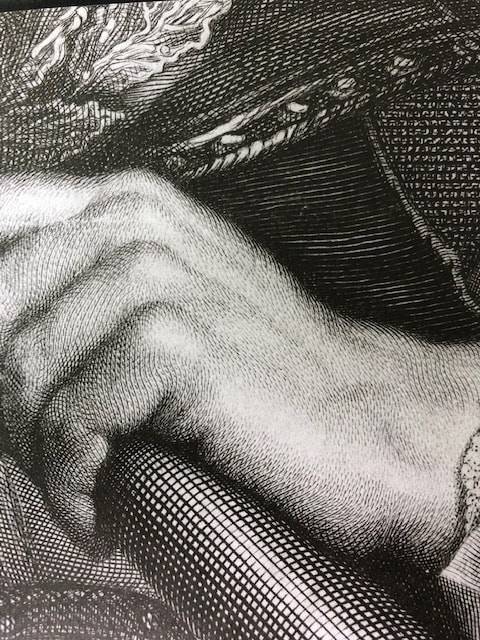

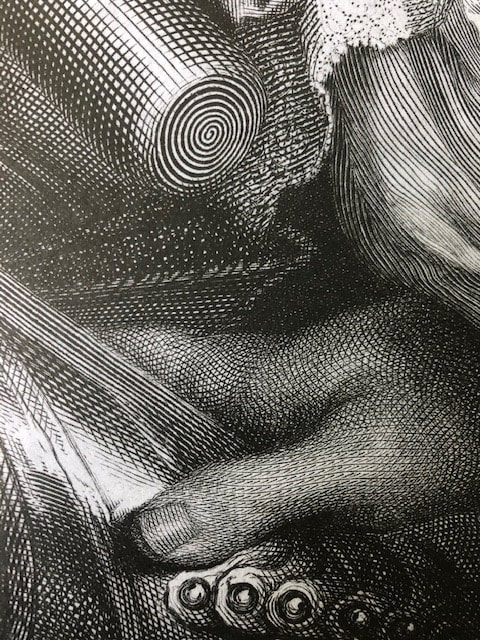

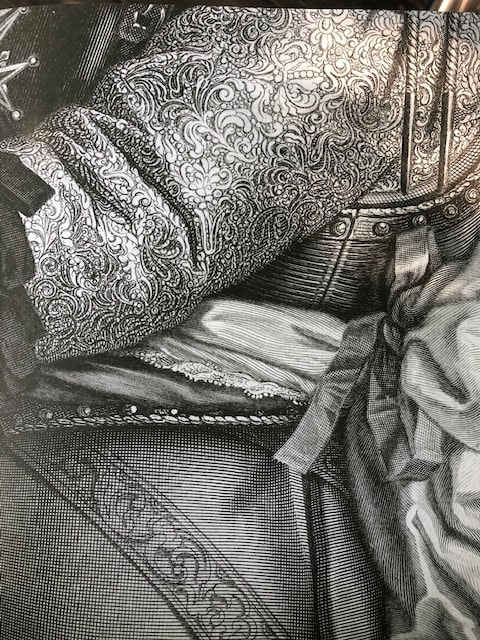

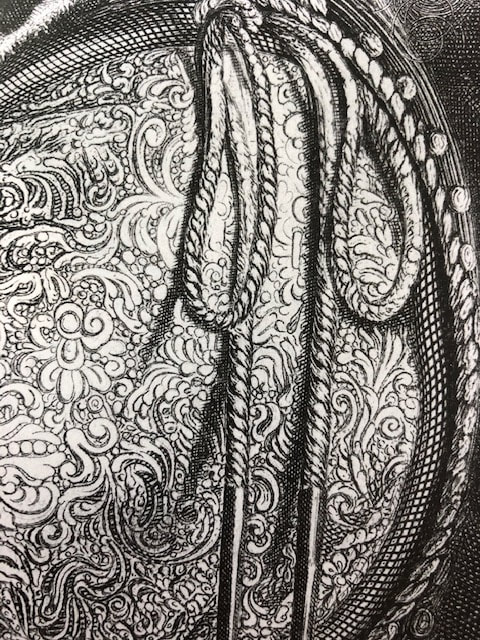

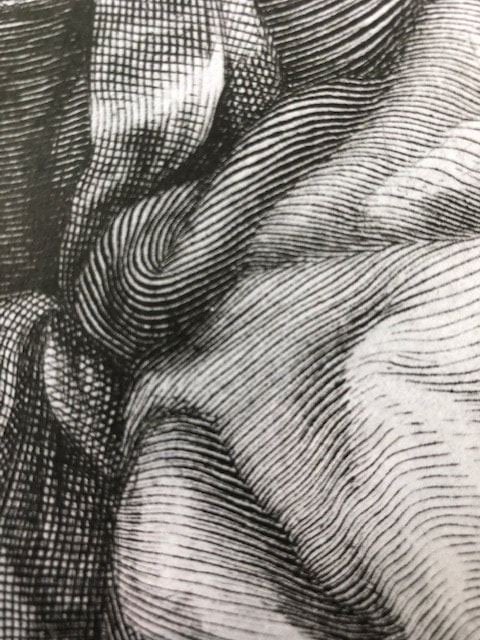

Ann ShaferOne of the reasons I love Stanley William Hayter so much is that I adore the quality of line he gets with engraving. In this method the artist uses a burin, a handheld tool with a diamond-shaped tip, to cut into the copper; they push the tool forward to incise a line in the copper into which the ink will lay. It takes a lot of strength and control, but it rewards the hard work. I love the swell and taper, the strength, the crispness. Hayter used engraving in a totally new way beginning in the 1930s. Prior to that the technique was used to reproduce the compositions of other artists. This type of print is known as a reproductive print. By these prints, the artist of the original composition could spread his designs far and wide, and the engraver could make a living. They were created by very talented engravers who devised a series of patterns of marks meant to mimic brushstrokes, fabric, hair, feathers, all the while in black and white. You can imagine that the advent of photography in the late 1830s killed this entire industry and engraving along with it. One hundred years later, Hayter revitalized the technique, but in a wholly new way. Reproductive prints are the bastard stepchild of the already bastard stepchild of prints, making them the bottom of the barrel. They don't get a lot of respect, but there has been a growing interest in them in the last few decades. Maybe they will soon have their day in the spotlight. I used to skim past these kinds of prints when going through solander boxes in the storeroom. They tended to be portrait after portrait of persons I didn't recognize or care about. They seemed trite, fussy, controlled, old fashioned, and are markedly different from the modernist prints of Hayter and the associated artists at Atelier 17. But as happens with prints, the more you slow down your looking, the more you see. As we used to say in the print room: "these reward scrutiny." I had a chance today to paw through Tru Ludwig's copy of Anthony Griffith's monumental book, The Print Before Photography (EDIT: not Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques, as first reported). The book is impressive, and the images are drawn solely from the collection of the British Museum. Its endpapers are a detail of a reproductive engraving by Antoine Masson of a portrait of Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt, by Nicolas Mignard from 1667. In the first few pages are more details plus the entire image. As you look through these details, check out how many different patterns are used and what they describe. This is when reproductive engravings get interesting for me: imagining an artist looking at a painting, or, more likely, a drawing of the painting, and attempting to render the flesh of the sitter's hand with black lines and dashes. Or the curling hair of his mustache. Or the shine of his satin sleeves. The list goes on. It truly boggles the mind. Antoine Masson (French, 1636–1700), after Nicolas Mignard (French, 1606–1668) Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt, 1667 Engraving Plate (trimmed within platemark) 544 x 390 (20 1/2 x 16 in.) British Museum: Bequest of Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode, R,6.209

1 Comment

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed