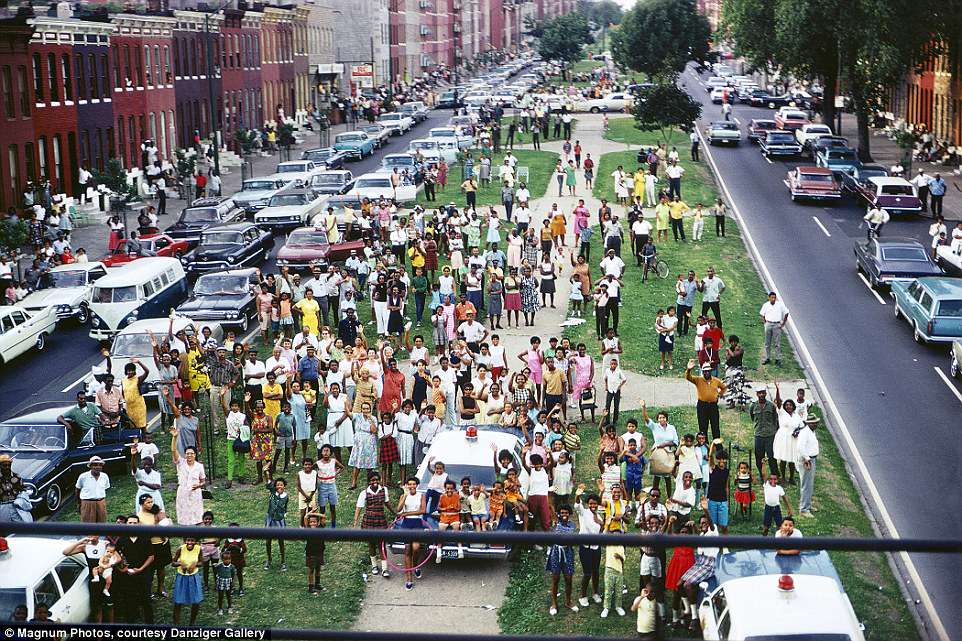

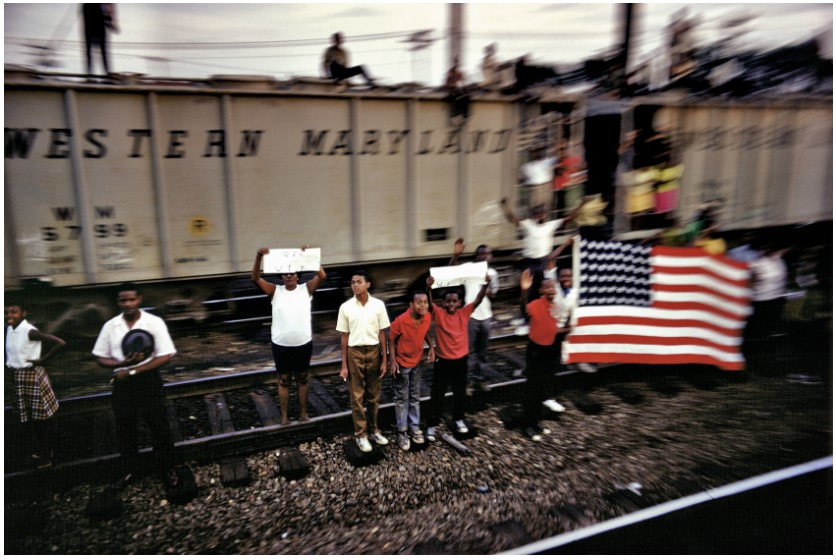

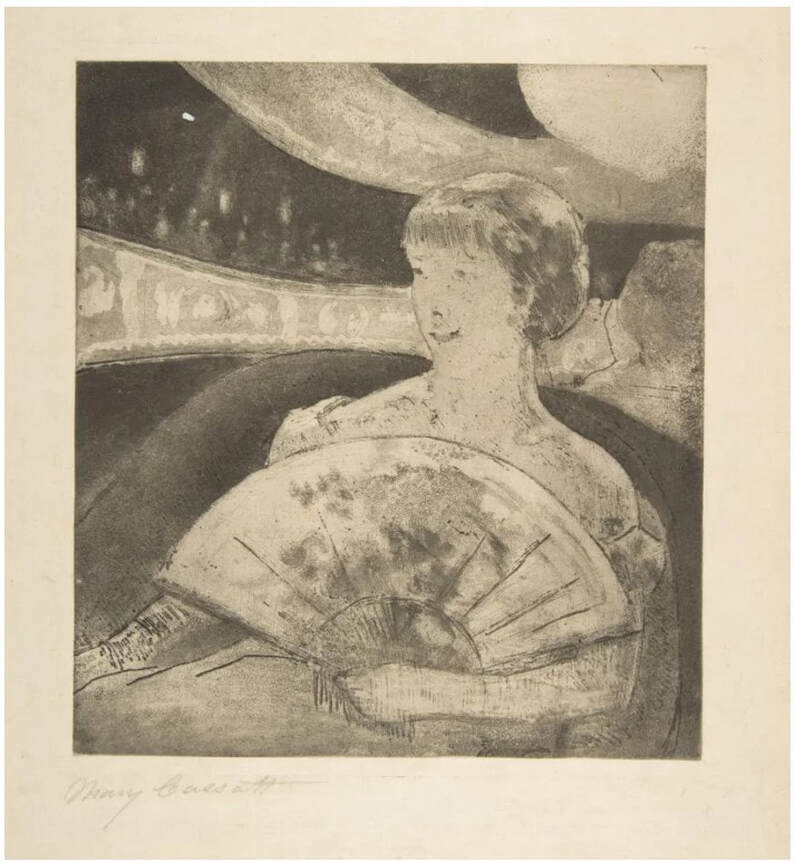

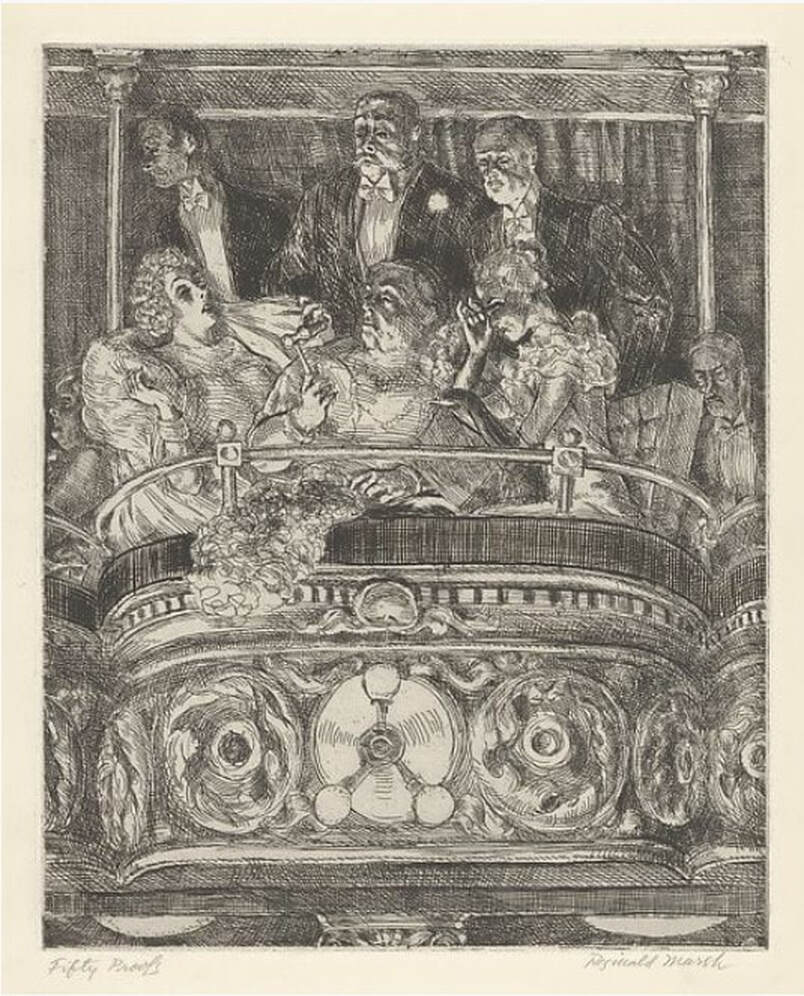

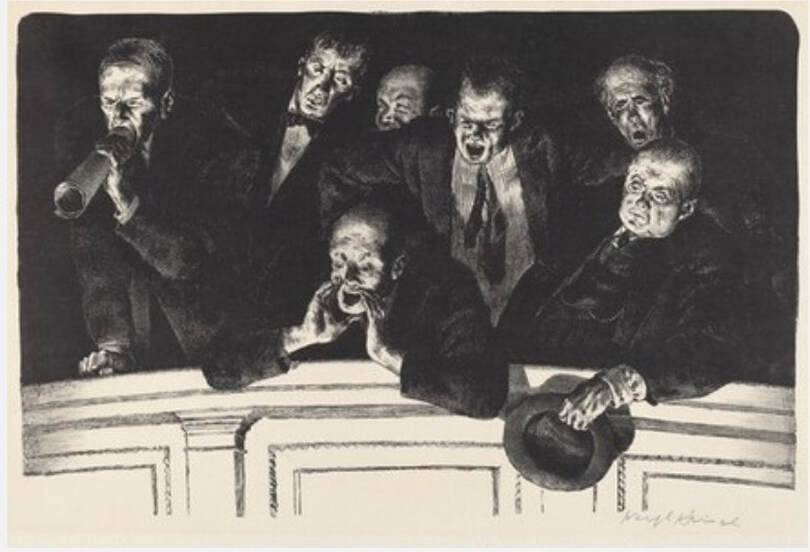

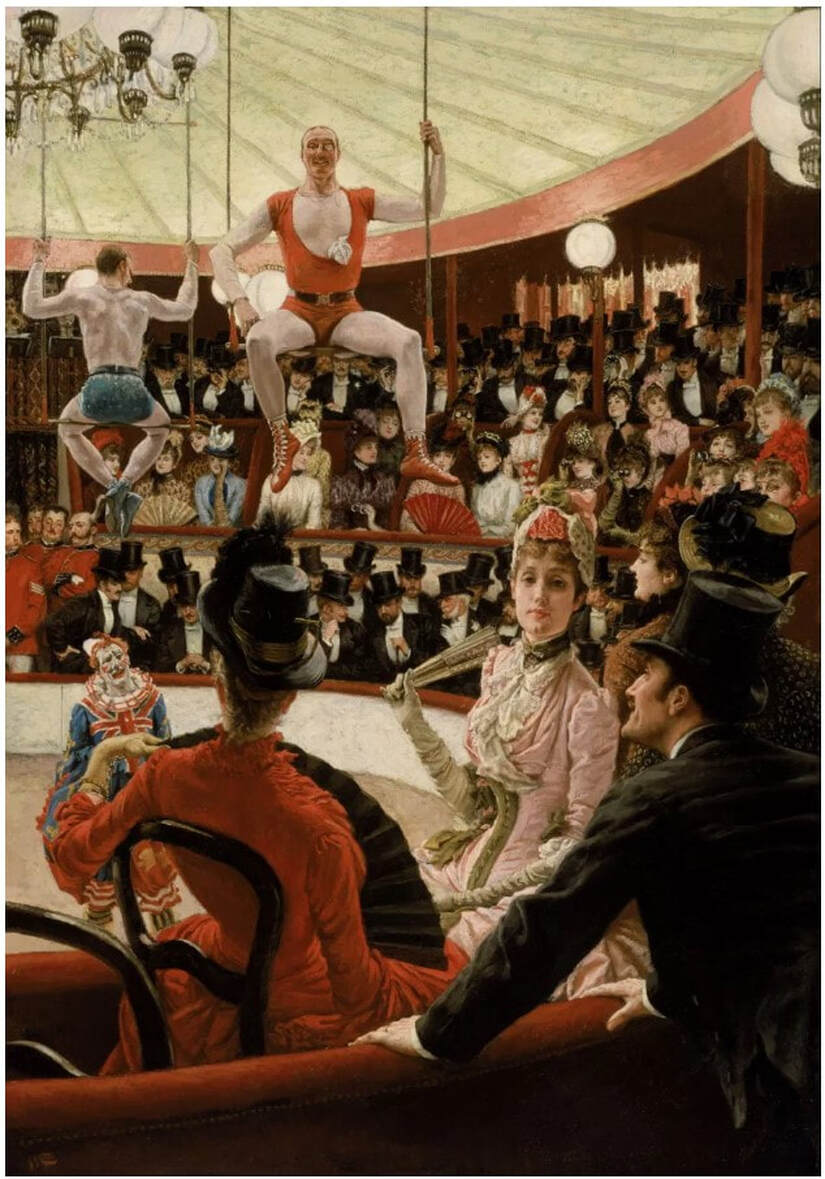

Ann ShaferI always wanted to do an exhibition about the audience. Portraying not the main attraction—the action on stage—but the people who are watching seems ripe for capturing a slice of life. The lookers being looked at flips convention. Voyeurism is a funny thing, alternately creepy and, what’s the opposite of creepy? Oh, pleasant. There are some great prints from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that would fit in this proposed exhibition nicely like Mary Cassatt’s In the Opera Box, 1879, Reginald Marsh’s Box at the Metropolitan, 1934, Joseph Hirsch’s Hecklers, 1943. Of course, there are plenty of paintings portraying audiences, too. My favorite is Tissot’s Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885. Though these images may seem quirky and quaint now, it is possible for an image of this type to cross over into social justice and to capture the zeitgeist. For me, one of the most searing group of images of an audience is Paul Fusco’s series taken in 1968 from the train carrying the body of Robert F. Kennedy from New York to Washington, D.C., for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The photographs capture an emotionally naked populace witnessing the end of optimism in the country. RFK’s assassination followed that of his brother, President Kennedy on November 22, 1963; Malcolm X on February 21, 1965; and Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968. RFK was shot just two months after Dr. King’s death, on June 5, 1968. By then, the country had seen more than its share of sorrow and senseless killing. The photographer, Paul Fusco, died last week, and it reminded me of how powerful the images are still. I marvel at how much emotion is conveyed across decades; they give me chills to this day. It may not surprise you to know that one of the photographs, a shot up North Broadway, just before the train dips underground on its approach into Penn Station in Baltimore, is one that got away. I pitched this photograph some years ago and got enough pushback to return it to the dealer. Part of the issue was that my colleagues weren’t convinced it was Baltimore in the photograph (of course it is), and the other had to do with vintage prints versus later reprints. Many curators seek and prefer to collect vintage prints, meaning the photographs were printed at the time they were shot. The photograph in question was a later printing, and thus was less desirable. I am certain Fusco wasn’t thinking in terms of museum collections in 1968. In fact, as a member of Magnum Photos, an international cooperative agency, he was on assignment for Look magazine, which published two of the photographs in black and white. The series was unknown until Aperture published it in 2008. Hence the later printings. In an earlier post I said I have never forgotten those that got away, and it’s true. To this day, when I see one of these works on the wall in some exhibition, I think “yes, I was right.” A few years after my failed pitch, I saw an exhibition of Fusco’s RFK train pictures at SFMoMA, and there was the North Broadway shot, front and center. Vindication. Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (North Broadway, Baltimore), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Family), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Western Maryland Railroad), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926) In the Opera Box (No. 3), c. 1880 Etching, softground etching, and aquatint Sheet: 357 x 269 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 9/16 in.) Plate: 197 x 178 mm. (7 3/4 x 7 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Imrie de Vegh, 1949, 49.127.1 Reginald Marsh American (1898–1954) Box at the Metropolitan, 1934 Etching and engraving Sheet: 250 x 202 mm. (9 13/16 x 7 15/16 in.) Plate 322 x 252 mm. (12 11/16 x 9 15/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of The Honorable William Benton, 1959, 59.609.15 Joseph Hirsch (American, 1910–1981) The Hecklers, 1943–1944, published 1948 Lithograph Sheet 312 421 mm. (12 5/16 x 16 9/16 in.) Image: 251 x 388 mm. (9 7/8 x 15 ¼ in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2503 James Tissot (1836–1902) Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885 Oil on canvas 147.3 x 101.6 cm. (58 x 40 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 58.45

0 Comments

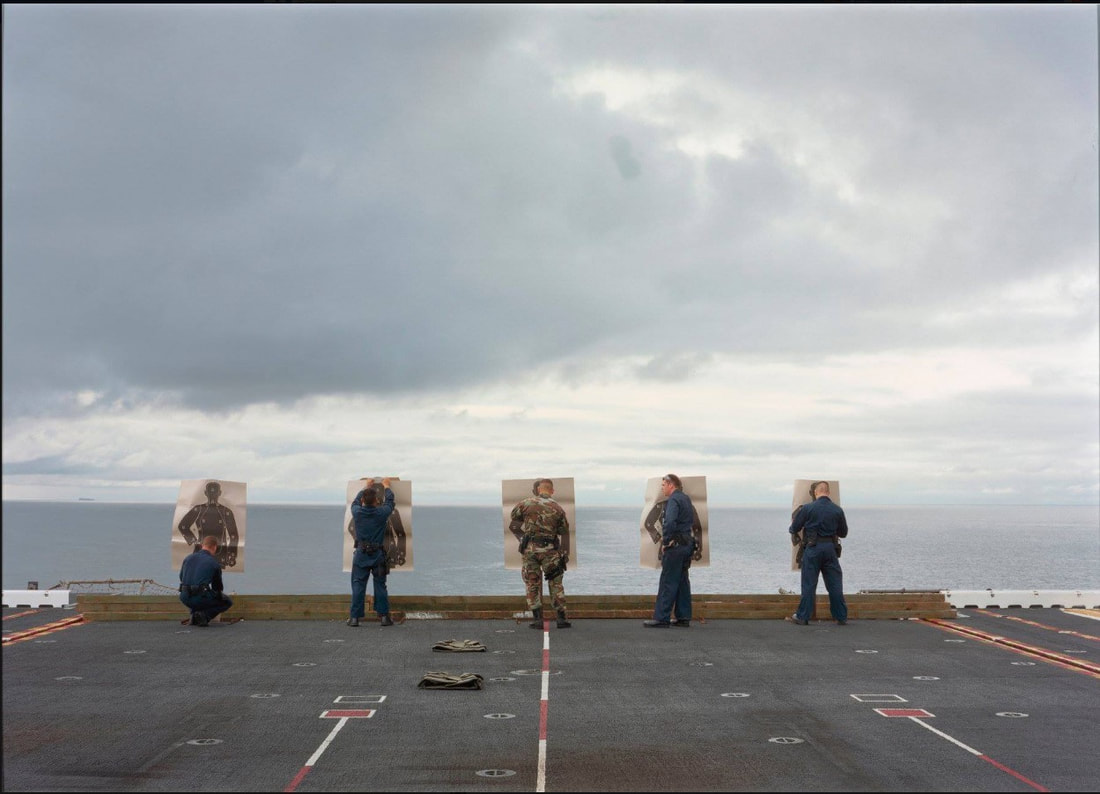

Ann ShaferFile this one under it's not always about prints and printmaking. In the fall/winter of 2013-14, the BMA showed the work of photographer An-My Lê (pronounced Ann-Mee Lay). It was an honor to work with her and, as often happens, the museum acquired one of the photographs from the show. When it came time to select objects to talk about on video for the BMA Voices initiative, this one was a no-brainer. It's got it all. Here's the link to the short video we made: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fuT0JHVXmE. In the brochure for the exhibition, I concluded in this manner: In their quiet, unassuming way, Lê's sublime landscapes remind us that war is complex and contradictory. Alongside the brutality of combat, there is also the thrill of danger and adventure. Where there is enormous loss, there is also honor. Where there is heated protest, there is also heartfelt patriotism. By calling attention to the global reach of the U.S. military, Lê's photographs point out how martial power is balanced by humanitarian assistance and support of scientific research. Any discussion of the military will be polarizing, but Lê is able to find equilibrium between opposing points of view. While her photographs appeal to conservatives who see her work as pro-military, they also speak to liberals who read her work as anti-war. In drawing back the curtain to reveal the inner workings of the military as a giant facet of the global economy, Lê's photographs encourage us to think about its many complexities. An-My Lê (American, born Vietnam, 1960) Target Practice, USS Peleliu, 2005 Inkjet print, pigment-based Sheet: 1016 x 1435 mm. (40 x 56 1/2 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2014.5 Ann ShaferSometimes you get lucky and come across an artist by chance whose work you love. Even better is when you become friends. I made a studio visit to an artist who happened to be married to Susan Harbage Page. Because their studios were adjacent, I was able to see both in one visit. Susan's work runs the gamut: photography, drawing, performance, fibers, writing. One project has always risen to the top for me. The Border Project is a long running exploration of immigration issues focused on the border at the Rio Grande river in Brownsville, Texas. (An exhibition catalogue about the project is available here: https://susanharbagepagedotcom.files.wordpress.com/…/1_bord….)

Long before children were being separated from their parents, Susan spent a lot of time photographing objects in situ and then collecting them. The objects left behind by migrants--bras, wallets, identification cards, shirts, toothbrushes--are catalogued and photographed in an anti-archive. The large-scale, color photographs of objects in the landscape hold power for me. Yet, sometimes no object is needed as evidence of a human presence. In Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, a human-sized divot in the dry, tall grasses has been recently used as a resting or hiding place after crossing the border from Mexico. Easy to miss, once we understand how these crossings occur, we will recognize signs like this one forever. This now-empty nest is simple, stark, potent, and full of untold stories both of hope for a better life and fear of capture. Susan Harbage Page (American, born 1959) Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, 2011, printed 2012 Inkjet print, pigment–based Sheet: 1067 × 1553 mm. (42 × 61 1/8 in.) Image: 965 × 1448 mm. (38 × 57 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of the Artist, BMA 2012.156 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed