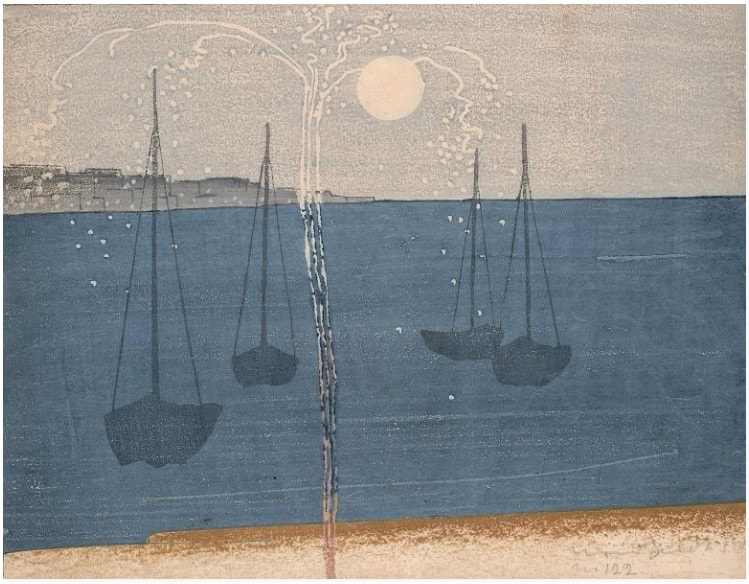

Ann ShaferI had the chance occasionally to acquire objects for the BMA’s collection at auction. It was always exciting, particularly when we won. The museum acquired an impression of this print, B.J.O. Nordfeldt’s The Skyrocket in this manner from Swann Auction Galleries in 2012.

The Skyrocket is my favorite of Nordfeldt’s woodcut compositions, which have a distinctive Japan-esque quality to them. (He also made etchings, which are more reminiscent of Whistler’s Thames series.) Inspired by 19th-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts, Nordfeldt developed a new method of printing color woodblocks. Instead of carving multiple blocks to carry individual colors in the Japanese manner, Nordfeldt carved images onto a single block, and inked each section with a different color. Sometimes, to keep colors separate on the block, small grooves were carved between each segment that create distinctive white lines in printing. This white-line style became a hallmark of his and other artists’ works made in Provincetown in 1916 and onward. That doesn’t appear to be the case here, and it is a decade before those works, but the design sensibility is definitely present. You should know that the image I’m showing here is the impression from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It’s slightly different in its printing, though the colors are similar. For instance, the BMA impression has less of that brown along the bottom. I can’t show the BMA’s impression because it is not included on the online database. Not every object is available on the website and I suspect it will be many years before the online database includes everything. More reasons to make an appointment to see the work in person after the pandemic has eased and museums reopen their doors to the public. B.J.O. Nordfeldt (American, born Sweden, 1878–1955) The Skyrocket, 1906 Color woodcut on Japan paper Image: 220 x 285 mm. (8 ¾ x 11 1/4 inches) Smithsonian American Art Museum: Gift of L. Laszlo Ecker-Racz

1 Comment

Ann ShaferIf ever I turned my attention to making art instead of writing about it, I would pull out my watercolors and brushes and head outdoors. It’s hard to imagine a world when that wasn’t possible—but it wasn’t so long ago that the first paints in tubes became commercially available. The first premixed watercolors were introduced to the market in England in the 1760s, but it wasn’t until the 1840s that those little tubes we know today were invented.

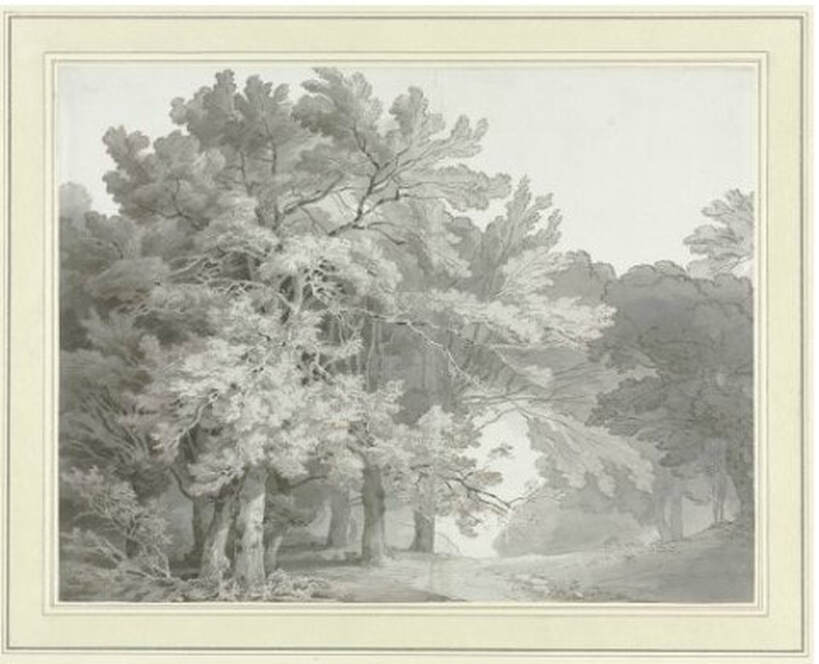

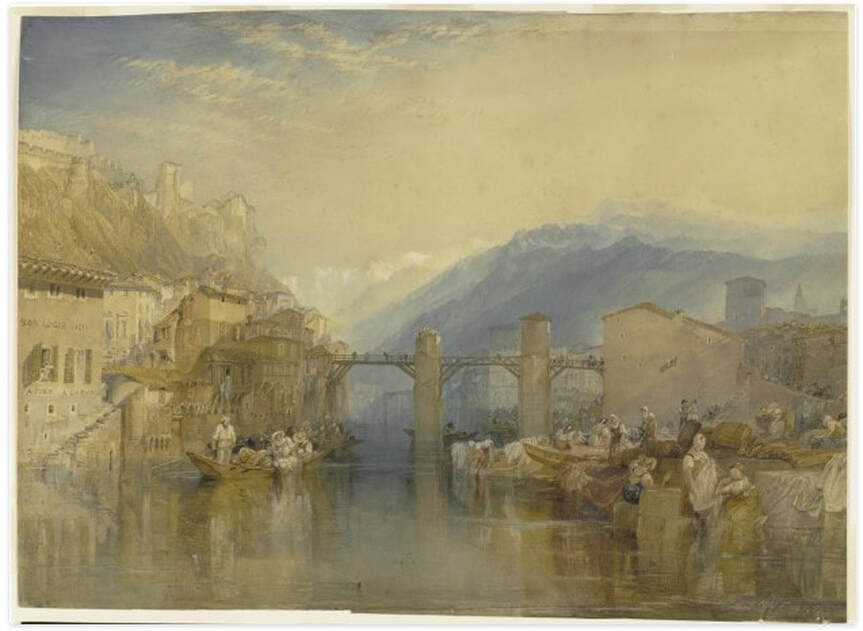

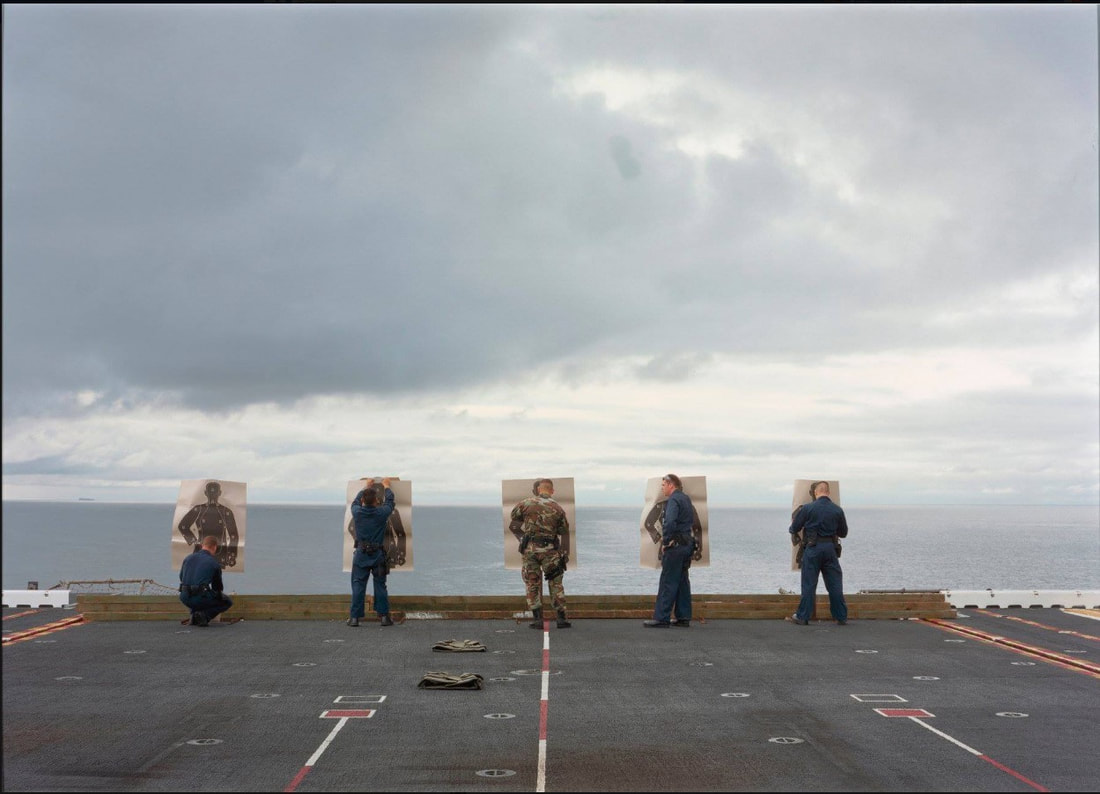

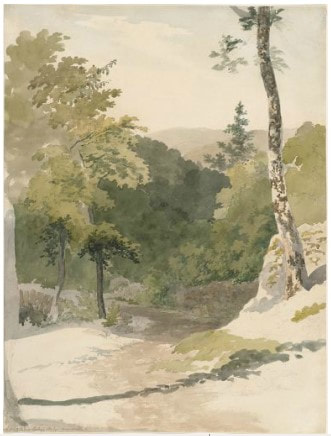

The proliferation of watercolor landscapes in England in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was due in no small part to the introduction of those premixed watercolor paints. Artists began to experiment with the medium and test the boundaries of what could be accomplished. Soon these works found their way into the annual exhibitions of the English Royal Academy, but they were so marginalized that a group of artists split from the Academy in 1804 to establish the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. The goal of this new Society was to place watercolors on an equal footing with oil paintings, and artists responded by creating large-scale, highly finished watercolors displayed in elaborate gold frames. The Baltimore Museum of Art is fortunate to have an example of one of these presentation watercolors by Britain’s favorite son, Joseph Mallord William Turner. In contrast to the highly finished exhibition watercolors, many artists created more intimate works in the same medium. Artists went outdoors with sketchbooks and paints to test their skills at portraying the landscape. One such work from a sketchbook (notice the crease down the center) is a favorite acquisition. The artist is John White Abbott, a country surgeon and apothecary from Exeter, who as an amateur artist painted for his own enjoyment (the term amateur indicates only that the artist did not earn money making art, but is no indication of a lack of talent). After inheriting an estate from his uncle, he was able to devote himself full time to painting. Abbott probably drew A Path through the Woods first in graphite pencil on the spot, and then returned to his studio to finish the work with gray washes and pen and brown ink. I continue to be amazed at the quality of light through the dappled foliage painted with just gray and brown. In fact, the execution is so masterful that I see this monochromatic scene in full color. In addition, the peacefulness of the scene always transports me to somewhere else. For me, this work is a figurative and literal breath of fresh air. John White Abbott (English, 1763‑1851) A Path through the Woods, c. 1785‑1795. Pen and brown and gray ink with brush and gray ink over graphite Sheet: 256 x 335 mm. (10 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Rhoda Oakley, Baltimore, BMA 2008.9 Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, 1775‑1851) Grenoble Bridge, c. 1824. Transparent and opaque watercolor with scraping over traces of graphite Sheet: 530 x 718 mm. (20 7/8 x 28 1/4 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased with exchange funds from Nelson and Juanita Greif Gutman Collection, BMA 1968.28 Ann ShaferFile this one under it's not always about prints and printmaking. In the fall/winter of 2013-14, the BMA showed the work of photographer An-My Lê (pronounced Ann-Mee Lay). It was an honor to work with her and, as often happens, the museum acquired one of the photographs from the show. When it came time to select objects to talk about on video for the BMA Voices initiative, this one was a no-brainer. It's got it all. Here's the link to the short video we made: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fuT0JHVXmE. In the brochure for the exhibition, I concluded in this manner: In their quiet, unassuming way, Lê's sublime landscapes remind us that war is complex and contradictory. Alongside the brutality of combat, there is also the thrill of danger and adventure. Where there is enormous loss, there is also honor. Where there is heated protest, there is also heartfelt patriotism. By calling attention to the global reach of the U.S. military, Lê's photographs point out how martial power is balanced by humanitarian assistance and support of scientific research. Any discussion of the military will be polarizing, but Lê is able to find equilibrium between opposing points of view. While her photographs appeal to conservatives who see her work as pro-military, they also speak to liberals who read her work as anti-war. In drawing back the curtain to reveal the inner workings of the military as a giant facet of the global economy, Lê's photographs encourage us to think about its many complexities. An-My Lê (American, born Vietnam, 1960) Target Practice, USS Peleliu, 2005 Inkjet print, pigment-based Sheet: 1016 x 1435 mm. (40 x 56 1/2 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2014.5 Ann ShaferSometimes you get lucky and come across an artist by chance whose work you love. Even better is when you become friends. I made a studio visit to an artist who happened to be married to Susan Harbage Page. Because their studios were adjacent, I was able to see both in one visit. Susan's work runs the gamut: photography, drawing, performance, fibers, writing. One project has always risen to the top for me. The Border Project is a long running exploration of immigration issues focused on the border at the Rio Grande river in Brownsville, Texas. (An exhibition catalogue about the project is available here: https://susanharbagepagedotcom.files.wordpress.com/…/1_bord….)

Long before children were being separated from their parents, Susan spent a lot of time photographing objects in situ and then collecting them. The objects left behind by migrants--bras, wallets, identification cards, shirts, toothbrushes--are catalogued and photographed in an anti-archive. The large-scale, color photographs of objects in the landscape hold power for me. Yet, sometimes no object is needed as evidence of a human presence. In Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, a human-sized divot in the dry, tall grasses has been recently used as a resting or hiding place after crossing the border from Mexico. Easy to miss, once we understand how these crossings occur, we will recognize signs like this one forever. This now-empty nest is simple, stark, potent, and full of untold stories both of hope for a better life and fear of capture. Susan Harbage Page (American, born 1959) Nest (Hiding Place), Laredo, Texas, 2011, printed 2012 Inkjet print, pigment–based Sheet: 1067 × 1553 mm. (42 × 61 1/8 in.) Image: 965 × 1448 mm. (38 × 57 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of the Artist, BMA 2012.156 Ann ShaferYou may not know that I have a secret passion for British watercolors of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The BMA has a glorious Turner presentation watercolor of Grenoble Bridge, but few companions. In 2008 I put together a small show featuring the Turner and was able to acquire this watercolor to augment the show and the collection. It's by Robert Hills, an artist best known as an animalier--one who specialized in painting animals. In this watercolor he captured the curve in the country road with the broken-down fence at left and singular tree at right. It's a crisp, lovely sheet--the whites are white and the colors strong--and it has all the features one wants in such a composition: a path leading the eye back in space, a framing tree and shadow, that broken down fence as a bit of nostalgia in industrializing Britain, the sense that it was painted on the spot (it likely was), and its uncontrolled picturesqueness. I think this was my first purchase for the collection. I love it still.

Robert Hills (English, 1769–1844) Nook End, Ambleside, c. 1807 Watercolor over graphite Sheet: 357 x 270 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 5/8 in.) The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from Bequest of Saidie A. May, BMA 2006.93 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed