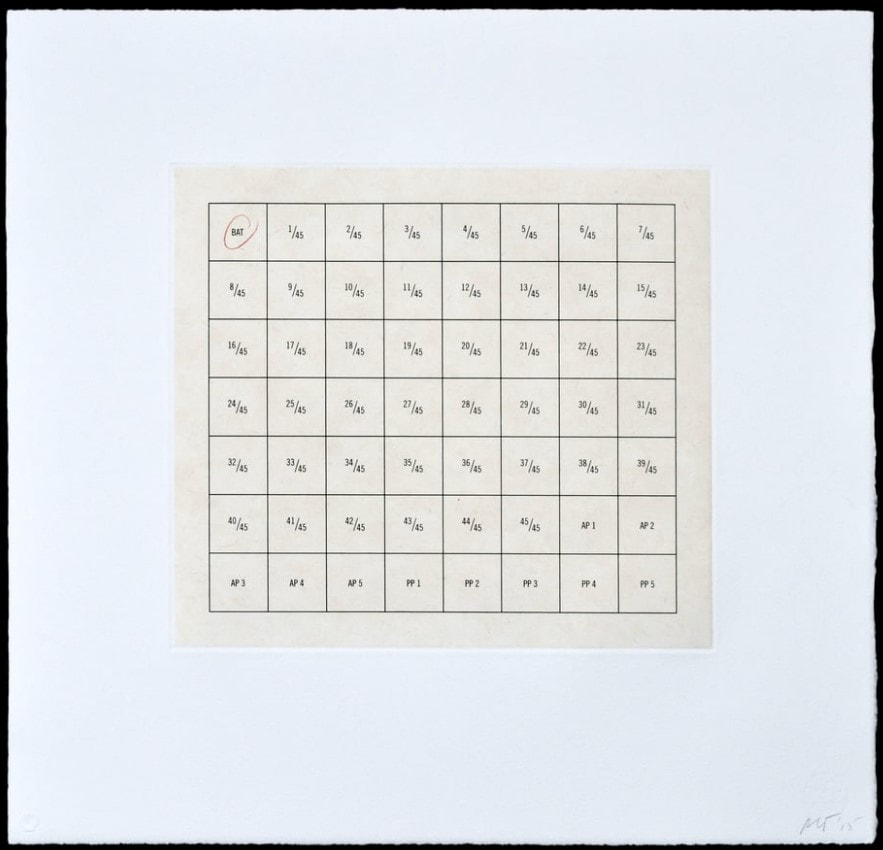

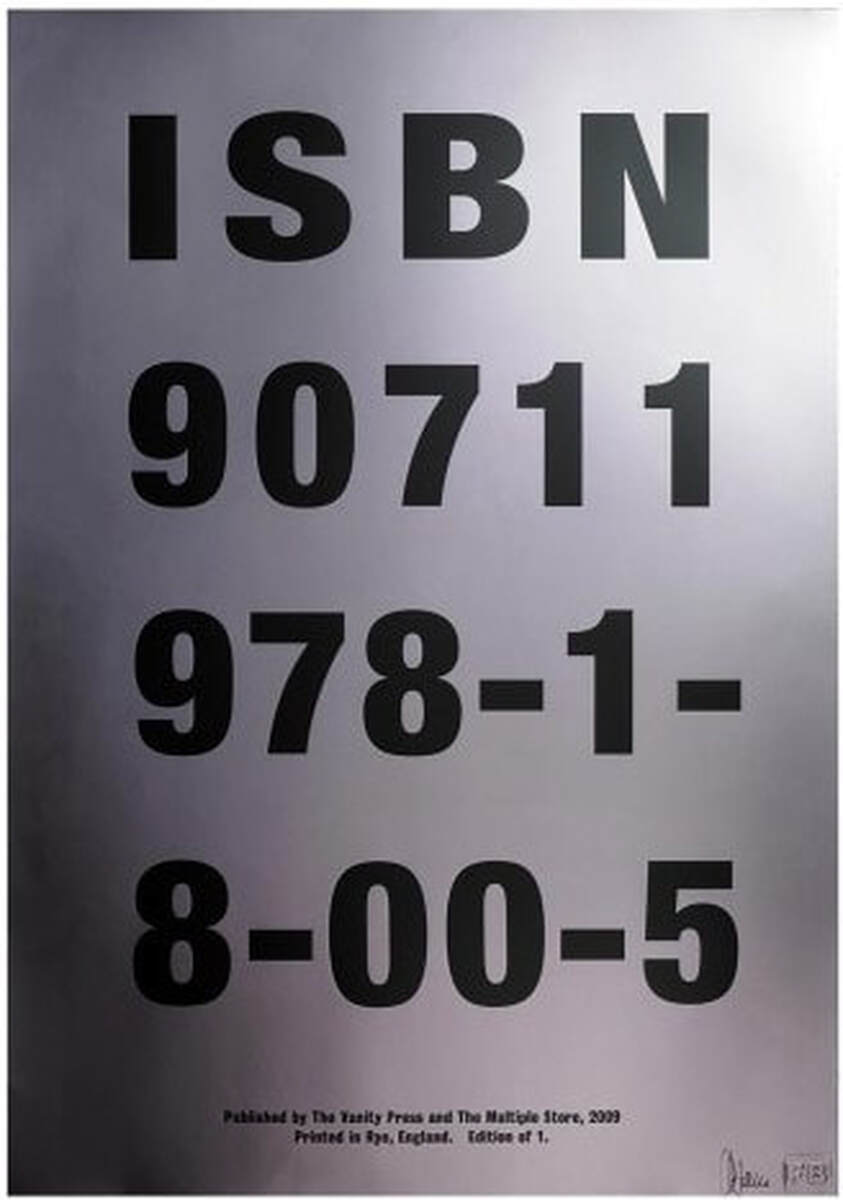

Ann ShaferLet's talk about editions, the idea of creating a limited number of a particular work of art—generally used in prints and multiples. The practice of limiting the number means that multiple collectors can possess the same image, that as the number dwindles an artificial rarity may create demand, and that artists control dissemination. (Know that the idea of a limited edition is a relatively new one, dating to the late-nineteenth century.) People often ask about editions and how it is that if there are more than one print, why are they considered original works of art and not copies. Basically, it has to do with the artist’s intention. (I can point you to the definition established by the Print Council of America here: https://printcouncil.org/defining-a-print/.) Printmakers naturally take advantage of the medium’s implicit multiplicity, but can the edition itself be the subject of an edition? How meta can it get? I like an artist who is aware of the structure of the enterprise. But is meta too clever, too cheeky? Is it possible to be funny, smart, aesthetically pleasing, and collectible? Check out this etching by Bill Thompson, which was printed by Jim Stroud at Center Street Studio. The print, Edition, 2015, is a minimalist composition featuring a simple grid. Inside of each square is a fraction running from 1/45 to 45/45—these reflect the numbers in the edition. There are also squares for one BAT (bon à tirer—meaning “good to print,” the proof an artist approves to proceed with printing), 1AP to 5AP (artist’s proofs), and 1PP to 5PP (printer’s proofs). These last few are outside the official edition of 45, but they often find their way into the market eventually. It may seem like they are special in some way, but this is artificial. For the most part, master printers will produce nearly identical impressions to such a degree that a print from the numbered edition will be no different from any of the proofs. Since all the possible impressions are represented within Thompson’s print itself, instead of the number getting handwritten below the image as is usual, in this case the artist circled each number in succession. So, the hand addition of the colored pencil circles indicates the number in sequence and also becomes the focal point of the image. It’s a visually elegant work, and its meta-ness is cheeky. (Impressions of Thompson’s prints are available here: http://www.centerstreetstudio.com/pur…/bill-thompson-edition). A second meta work is Fiona Banner’s Book 1/1, 2009, published by the now defunct The Multiple Store. The work is more print than book for it is simply bold black letters on a single piece of mirror-finish card. The type spells out the ISBN number of the books—each individual book, that is. Each ISBN (International Standard Book Number) number is registered—it’s an official publication full of nothing, containing only its registration information. Because books are usually reproduced in great numbers, that each of Banner’s books is unique plays against the norm. In addition, the mirror finish performs an important role. Because the viewer necessarily sees him/herself in the reflection, they are automatically the subject of the image/book. In addition, because of the reflective surface, the books are also impossible to photograph and reproduce well; their uniqueness is even more firmly established. Any image of said book will necessarily be different depending on the reflections caught in the process. Banner’s work is a published and registered book, without contents, unreproducible, unique, and reflects the viewer. Talk about meta! Bill Thompson (American, born 1957) Printed and published by Center Street Studio Edition (BAT), 2015 Etching with chine collé Sheet: 546 x 565 mm. (21 ½ x 22 ¼ in.) Plate: 318 x 368 mm. (12 ½ x 14 ½ in.) Fiona Banner (British, born 1966) Published by The Vanity Press and The Multiple Store Book 1/1, 2009 Block print on mirror card 685 x 492 mm. (27 x 19 ½ in.)

0 Comments

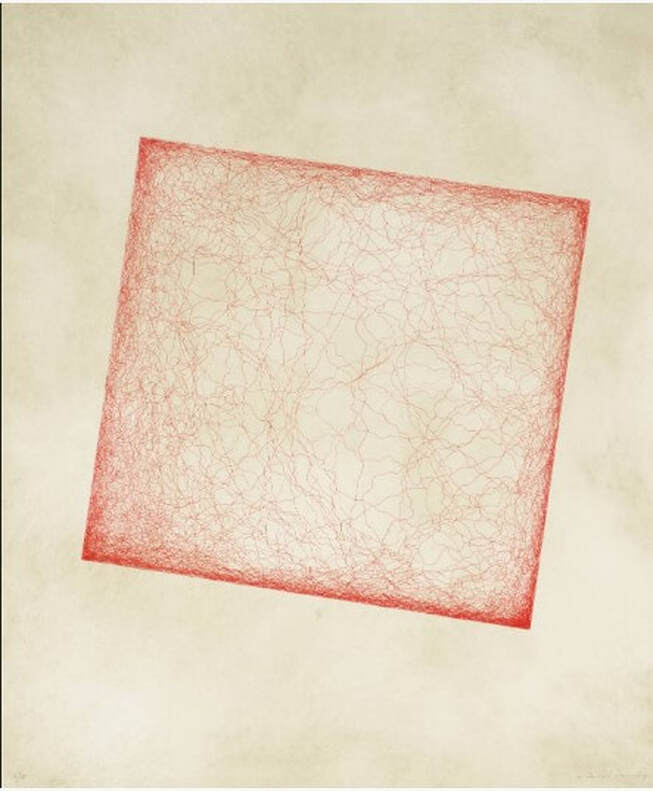

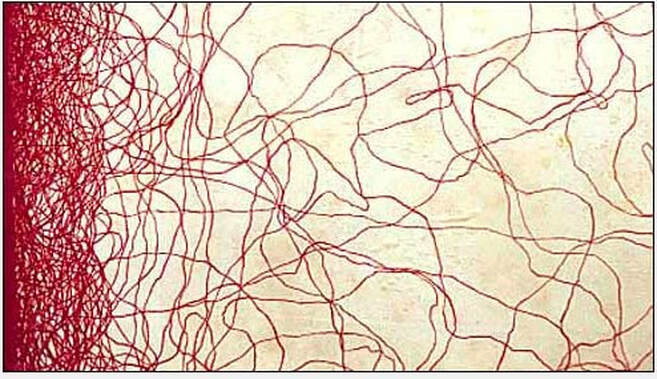

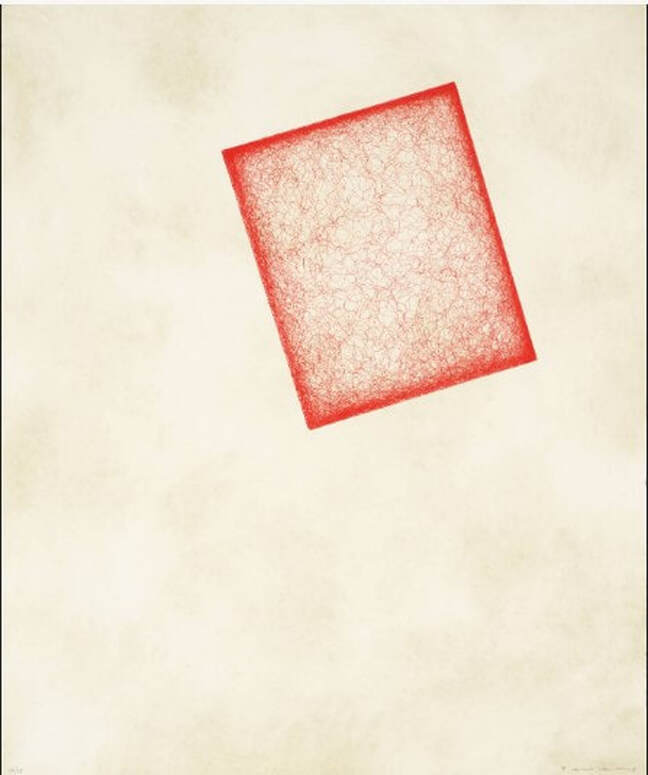

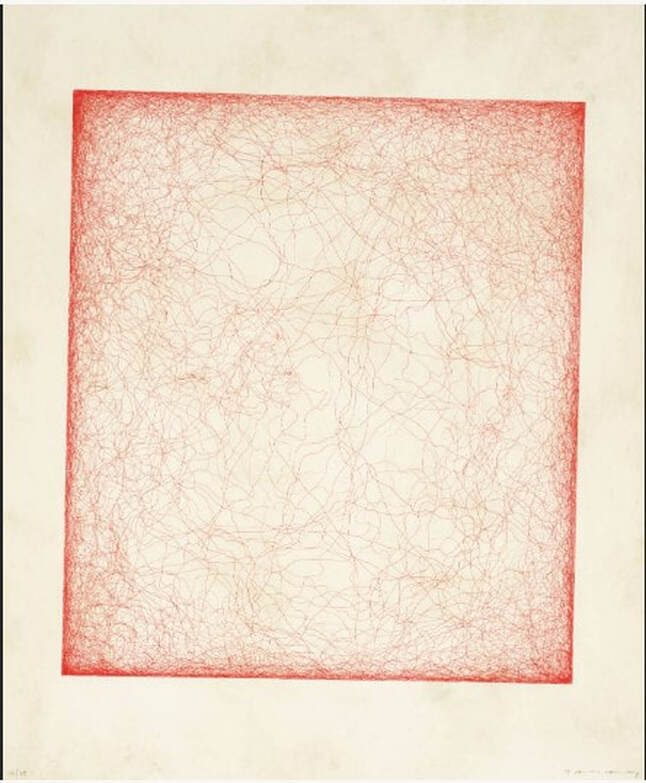

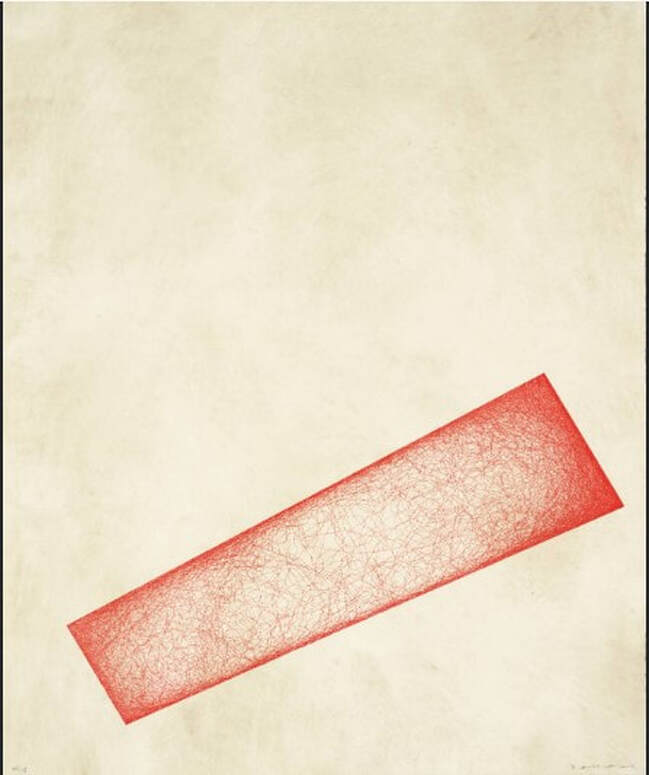

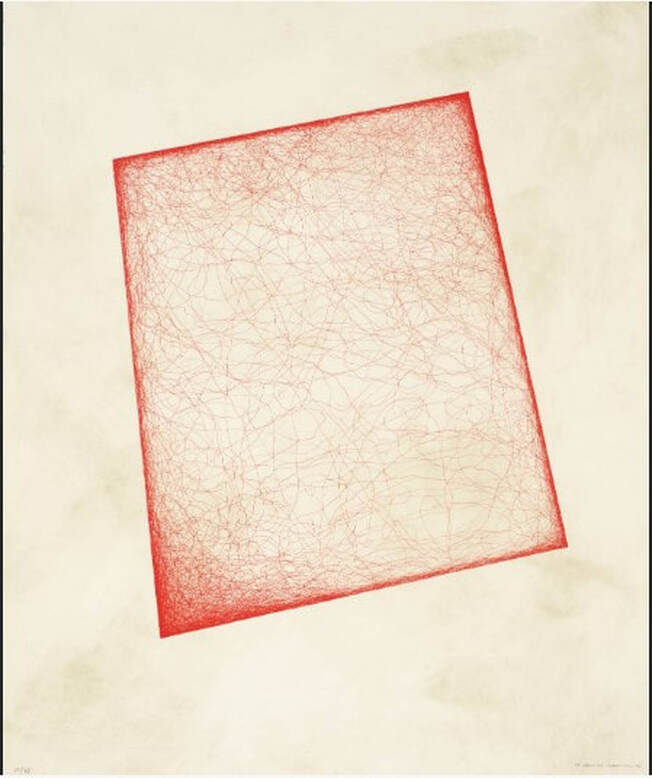

Ann ShaferIs the Enlightenment really the Endarkenment? It’s one thing to strive to understand and organize all human knowledge, and it is another thing to use that knowledge to justify the enslavement of a people and the subjugation of women. Stay with me here.

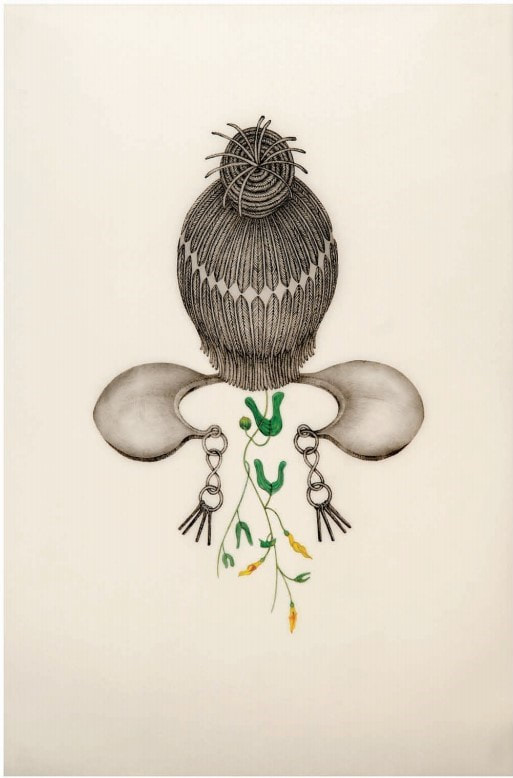

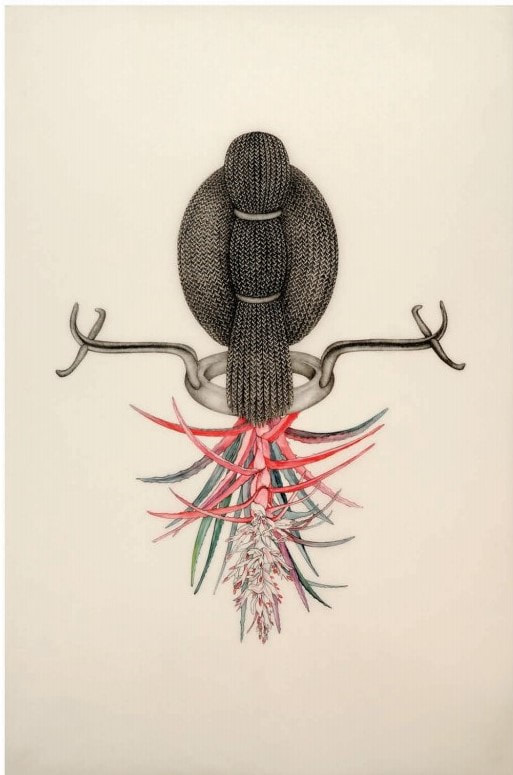

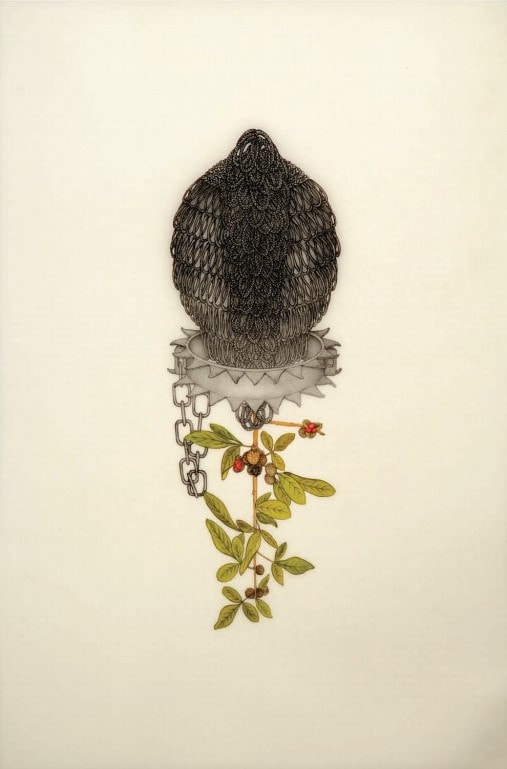

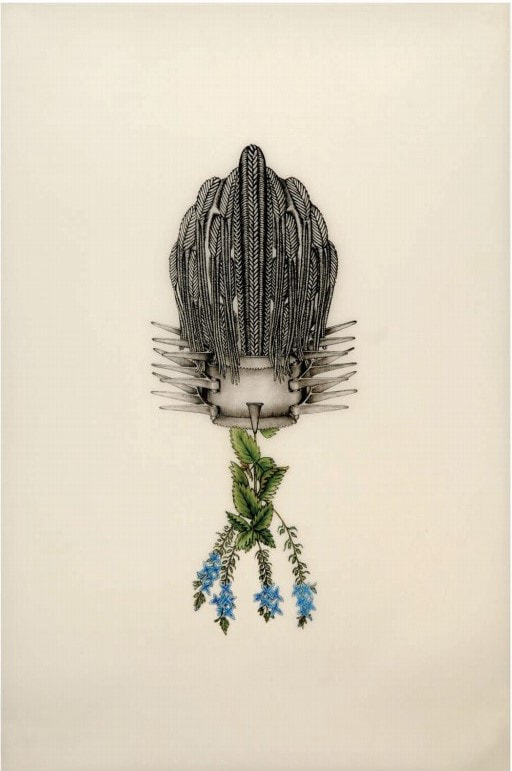

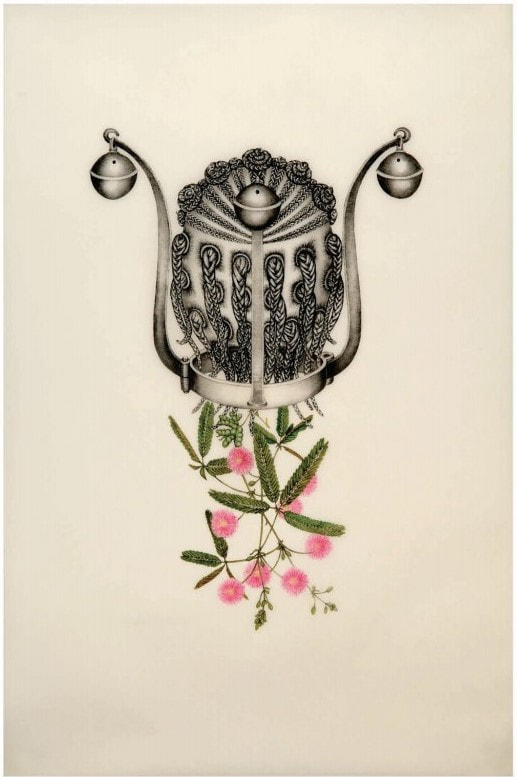

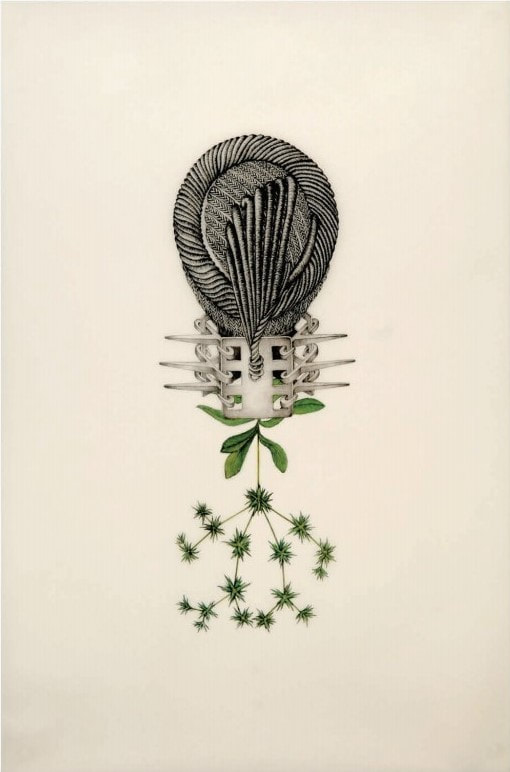

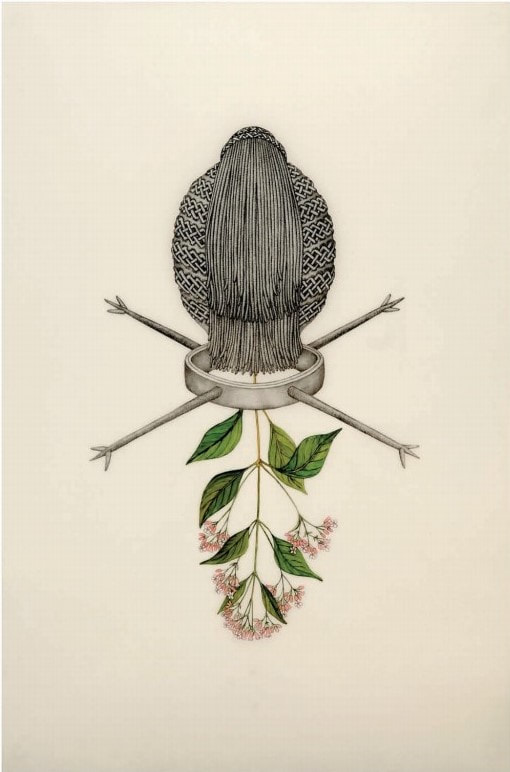

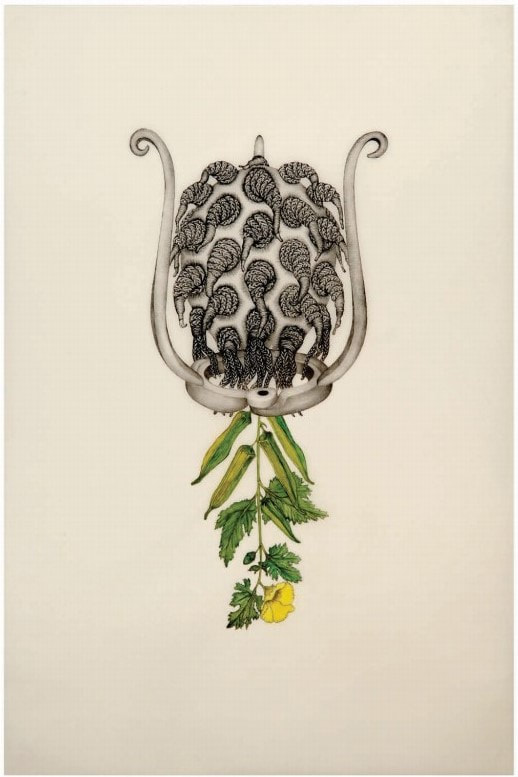

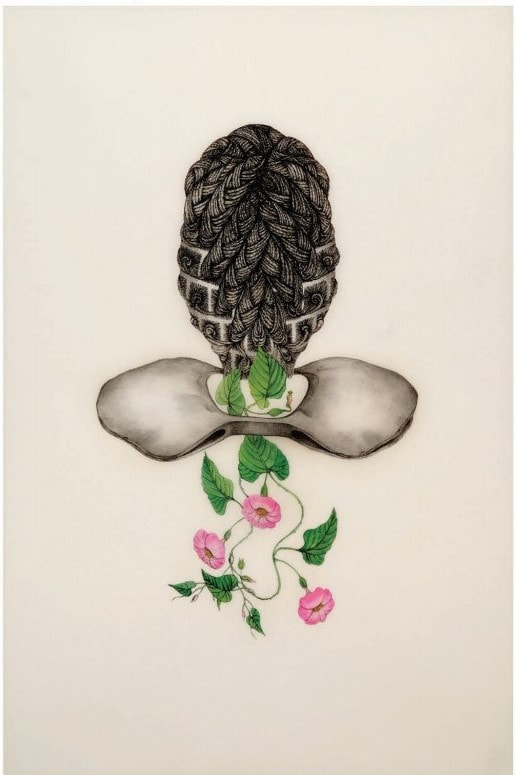

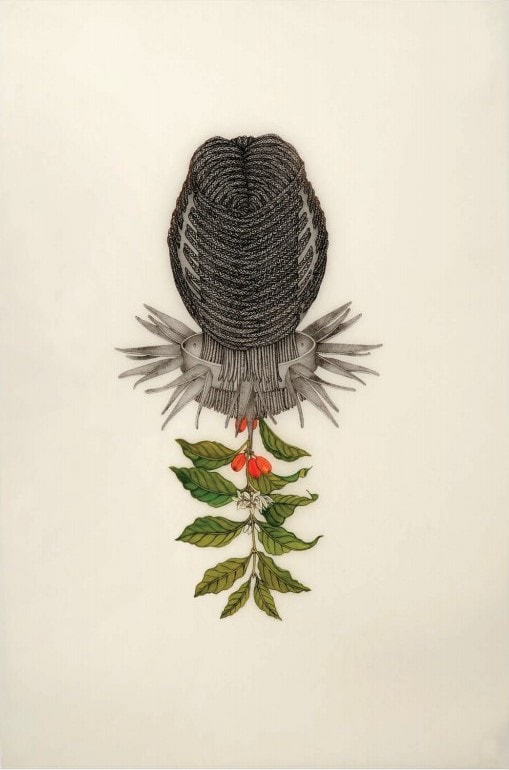

On a recent, long drive, we started listening to Isabel Wilkerson’s new book, Caste. The recording is fourteen hours long, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. In fact, we’re still in the eight-pillars-of-the-caste-system part that sets up the whole thing. It’s dense, intense, and important. One of the pillars was an ah-ha for me. It has to do with heredity, the idea that one’s caste is inherited through family. In most cultures, this placement into a certain level of society follows the patriarchal line. In America, however, from its earliest days, caste was passed down through the matriarchal line. This turnabout was necessary because it enabled the upper caste (white men/slave owners) to rape enslaved women in order to produce yet more slaves that could add to the labor force or be sold for a profit. Rape as a profit center. It makes me sick. Maybe I’m naïve for being surprised, but that one really got to me. WTAF?!? After the trip, a friend/colleague mentioned the artist Joscelyn Gardner's portfolio, Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers…, 2009–11, and I knew it would make a powerful post. It also felt like no coincidence that she told me about the works at the same time I’m deep in Wilkerson’s book. I have never resisted talking about and introducing you to works that pack a political punch. Hold on to your hats, here we go. First, know that Gardner’s portfolio intertwines information gleaned from the papers of an English slaveholder and amateur botanist named Thomas Thistlewood who settled in Jamaica in 1750. His papers are well known and are one of the fullest and most extensive accountings of that period, including everyday matters having to do with the slave business, the weather, horticulture and botany, crops, and financial issues (they are held by Yale’s Beinecke Library). In addition, the papers include a meticulous accounting of his violent sexual transactions. Scholar Alison Donnell (in an exhibition catalogue featuring Gardner’s work from 2012) uses the term transaction because Thistlewood recorded in excruciating detail some 3,852 acts of intercourse with 138 women. He was no sex addict. Donnell goes on to pose these pertinent questions: “How do we represent the violence and violation of slavery without repeating its spectacular effect? How do we speak about subjects lost to history and yet not entirely unknown? How can we make visible the systems of representation that support an unequal distribution of authority, knowledge, and power?” Enter the artist Joscelyn Gardner. She grew up in Barbados where her family dates back to the seventeenth century—one can only assume they were land- and slaveowners—and now calls London, Ontario, home. In her portfolio of twelve lithographs printed on frosted Mylar (lending a particular luminescence), each portrait includes the head of an African woman seen from behind showcasing an elaborately braided hairstyle, a complicated torture device, and a delicate botanical specimen. The delicacy and intricacy of the rendering draws viewers in; it is an oft-used trope that usually works. In traditional portraiture, the subject faces the viewer, often confronting them. Portraits were created to showcase the sitter’s stature, knowledge, and wealth. Yes, these would be mostly men. Women were often portrayed as allegorical figures (nude, naturally), or in relation to the men in their lives. Gardner’s subjects have their backs turned to us, preventing us from knowing who they are individually. This does several things. It not only subverts the male gaze and objectification, but also allows the artist to portray women whose identities are lost to history. For me, they become symbols of the strength and determination of enslaved women without the spectacle of their circumstances. This seems especially appropriate in this instance because the artist herself is white. (This is a much larger debate that requires its own post.) In Gardner’s hands, the hair is the manner of capturing character as she bears witness to lives lived. The elaborate hairstyles of meticulous braiding mark each as an individual, but also reflect the sisterhood required to accomplish them. These hairstyles are based on contemporary examples tying the past to the present and acknowledging hair’s position as a signifier of personhood, status, and position, as well as being a key means of individual expression. But remember, hair is also a fundamental means of differentiating race and class. During slavery, the worn instruments of torture were visible manifestations of control and systematic enforcement of authority. Interestingly, depictions of bucolic plantation life appear in contemporaneous artworks, but few examples exist showing the habitual violence necessary for keeping the system operational. More truthful imagery begins to surface with the Abolitionist movement at the end of the eighteenth century, but the subjects are faceless—a continued effort to dehumanize slaves. This is surprising when one considers the power of postcards of lynchings produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that were widely shared and had the effect of reinforcing that terror. Perhaps the pastoral images of exotic plantations for a European audience naturalized the injustices that were codified into laws making men and women the property of others. By subverting accepted narratives of the era, Gardner recognizes slave women, gives them a voice and a presence. Representation matters. As the world became fascinated with classification of things, the definitions of words, the knowledge of how things worked, of Enlightenment, was this all code for “we have to justify the subjugation of ‘other’ human beings in order to build a new world?” The botanical specimens Gardner adds to each portrait echo the style of eighteenth-century books cataloging plants with exquisitely delicate illustrations. Gardner includes their Latin names—a colonizing effect wholly tied to European conventions of the study of natural history, which was a booming industry in the print trade in the eighteenth century. The names set in parentheses are not the common names of the plants but the names of slaves from Thistlewood’s diaries, reflecting another colonizing act in which the assignment of names was arbitrary and separated slaves from their African identities—more subjugation and dehumanization. But the applied knowledge of plants has long been the domain of women, and whose use has long been distrusted by men. Remember healers were thought to be witches in the early years of the Republic? In Gardener’s prints, these particular plants are in fact Abortifacients, which were used to abort unwanted pregnancies. Gardner’s portraits allow these women to control the male gaze upon them, display individualism through hairstyles, acknowledge but transform the objects of torture, and twist Thistlewood’s intense interest in botany to identify plants used to counter his attempts to impregnate and profit from the births of black bodies carried by women with few options. Notes: The portfolio was printed at Open Studio, Toronto, with master lithographer Jill Graham. See the thorough and thoughtful catalogue on Gardner’s work that includes essays by Jennifer Law, Alison Donnell, and Janice Cheddie here: https://fcd17b62-2ec4-4ce5-8701-cf90a26cd17a.filesusr.com/…. Joscelyn Gardner (Barbadian and Canadian, born 1961) Printed by Jill Graham, Open Studio, Toronto Aristolochia bilobala (Nimine), 2010 Bromeliad penguin (Abba), 2011 Trichilia trifoliate (Quamina), 2011 Veronica frutescens (Mazerine), 2009 Mimosa pudica (Yabba), 2009 Eryngium foetidum (Prue), 2009 Cinchona pubescens (Nago Hanah), 2011 Hibiscus esculentus (Sibyl), 2009 Manihot flabellifolia (Old Catalina), 2011 Convovulus jalapa (Yara), 2010 Petiveria aliacea (Mirtilla), 2011 Coffee arabica (Clarissa), 2011 From the portfolio Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers… Portfolio of twelve lithographs with hand coloring on frosted Mylar Each sheet: 915 x 610 mm (36 x 24 in.) Ann ShaferIn the BMA’s study room, I welcomed classes from area colleges and high schools and enjoyed the groups from MICA the most. I loved showing young artists works that made their brain synapses fire. You could see them igniting. Sometimes it was fun to play the “how was it made” game. Usually these works were conceptual in that there is a set of rules governing the making, and also indexical in which the image is of its own making. One such drawing by Baltimore artist Denise Tassin always made the cut. The BMA’s online database doesn’t include the drawing so I can’t show you the actual work, but it is similar to the version I posted below (know that the paper is bright white, not pink). The abstract image is on a large sheet and is made of only red ink. Sometimes the students would guess correctly: Tassin used earthworms and red pigment to create the image. In some of the marks one can discern the ribbed rings of the worms’ two ends, which were usually the giveaway. It’s a beautiful drawing and enables a discussion about conceptual works of art in which a set of rules are established and followed. In this case the rules are simple: the worms are allowed to wriggle around for X time, no other intrusions interrupt the process. Next, I would pull out another critter-based work: the portfolio Wandering Position by Japanese artist Yukinori Yanagi. Coincidentally also in red ink, the five untitled sheets in this portfolio are etchings and the featured insect is an ant. On a plate coated with a hard ground, the artist followed the ant with an etching needle, tracing its path in the confined shape. Looking closely reveals the ant’s repeated attempts to get out; there is a marked build-up of lines in the corners and against the boundary. I suspect the rules included a time limit in which to follow the creature. And here is another indexical image. Yanagi didn’t draw an image of an ant traversing a space, rather, the ant’s recorded path is the image. The students seemed to love the portfolio; they always reacted with a hearty “ooh!” It’s such a simple concept really, following a bug with an etching needle. But there’s more to it. There’s a weird power struggle here, a both/and situation. The tiny and vulnerable ant is in charge of the artist’s labor and yet is confined to a prescribed space. On the other hand, the artist is at the whim of the bug and is also in control of the situation. In this and in other works Yanagi looks at issues of control in society, drawing a through-line from borders, nationality, and migration to incarceration. (The artist created an installation piece at Alcatraz in 1996.) I always strove to show works that expanded what was possible as well as different modes of art making. Yanagi’s portfolio is an intriguing set of prints that always resonated with young artists. Denise Tassin (American, born 1966) Drawing by Worms Red ink Denisetassin.com Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959) Wandering Position, 1997 Printed by Harlan & Weaver Published by Peter Blum Editions Sheet (each): 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.) Portfolio of five etchings printed in red Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5  Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5.  [DETAIL] Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5.  Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5.  Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5.  Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5.  Yukinori Yanagi (Japanese, born 1959). Untitled, from the portfolio Wandering Position, 1997. Printed by Harlan & Weaver; published by Peter Blum Editions. Sheet: 615 x 510 mm. (24 3/16 x 20 1/16 in.). Etching printed in red. Baltimore Museum of Art: Women's Committee Acquisitions Endowment for Contemporary Prints and Photographs, BMA 2001.352.1–5. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed