Ann Shafer One of the exhibitions I curated for the BMA, Alternate Realities, was a true highlight for me. This was back in the fall of 2014 when the prints, drawings, and photographs department had a small gallery in the contemporary wing for rotating exhibitions drawn from the permanent collection. It was a single room and just big enough to mount a small but meaningful show on a single topic. In this case, I was able to include nine works of art: two were multi-part portfolios, one was an artist’s book in a case, and the rest were prints framed on the wall.

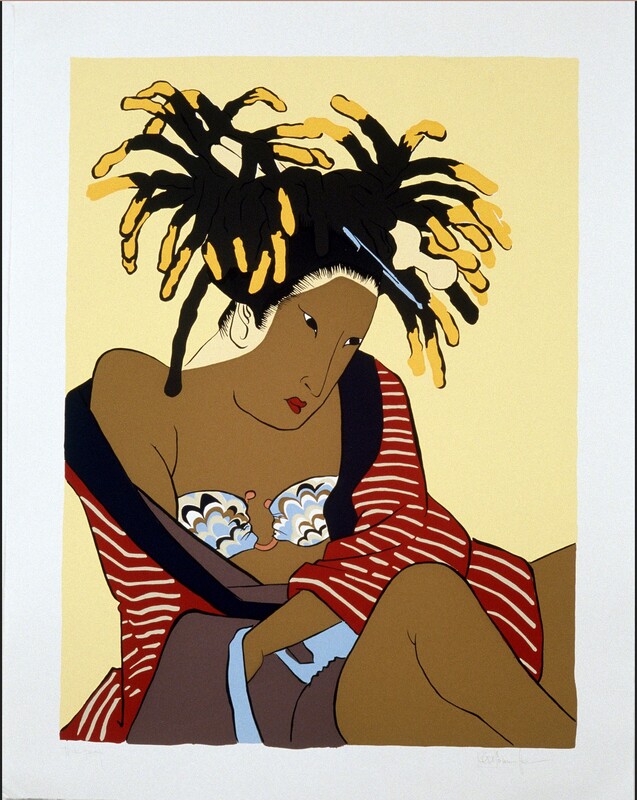

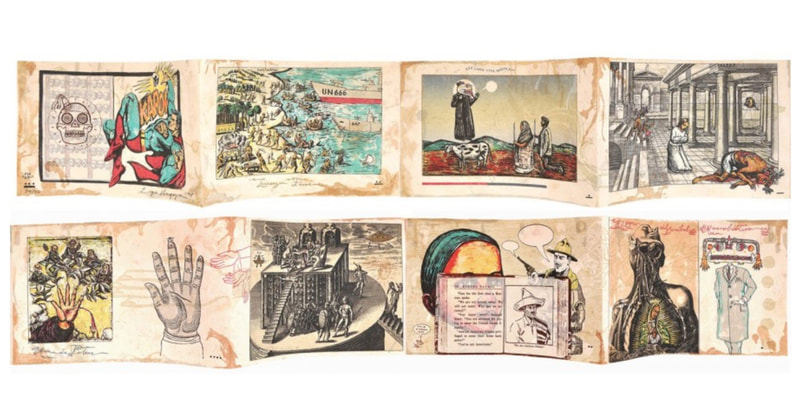

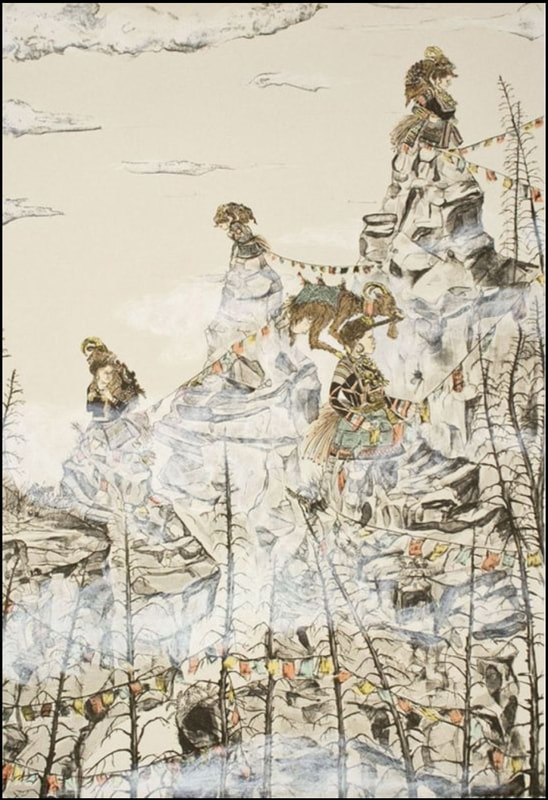

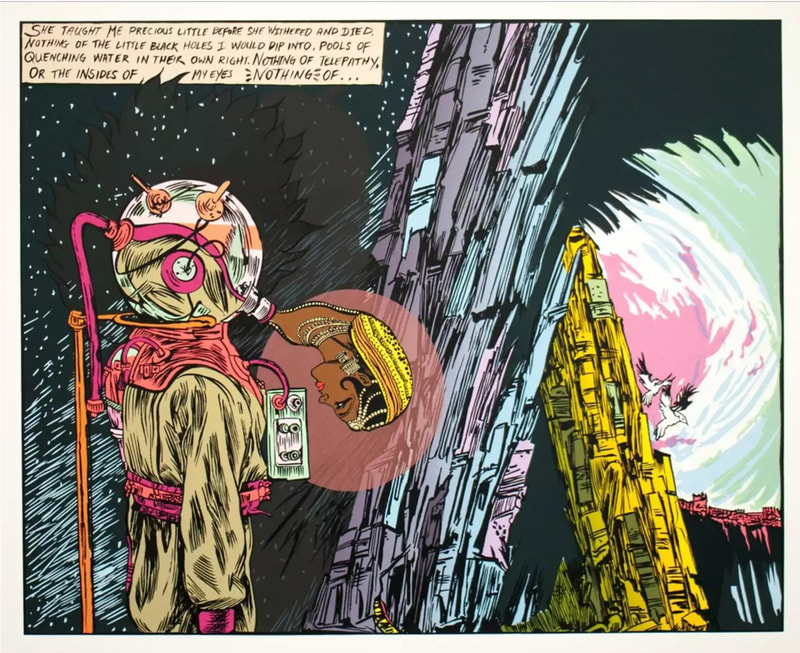

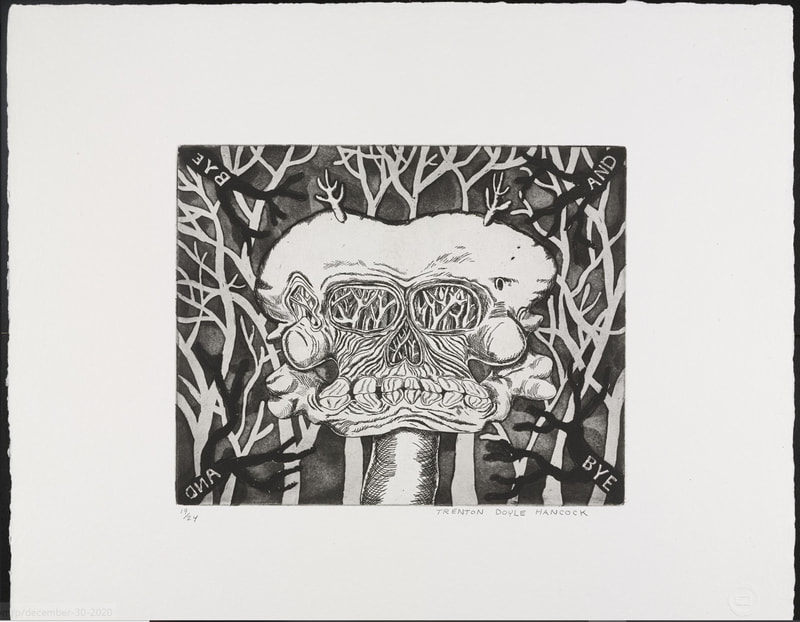

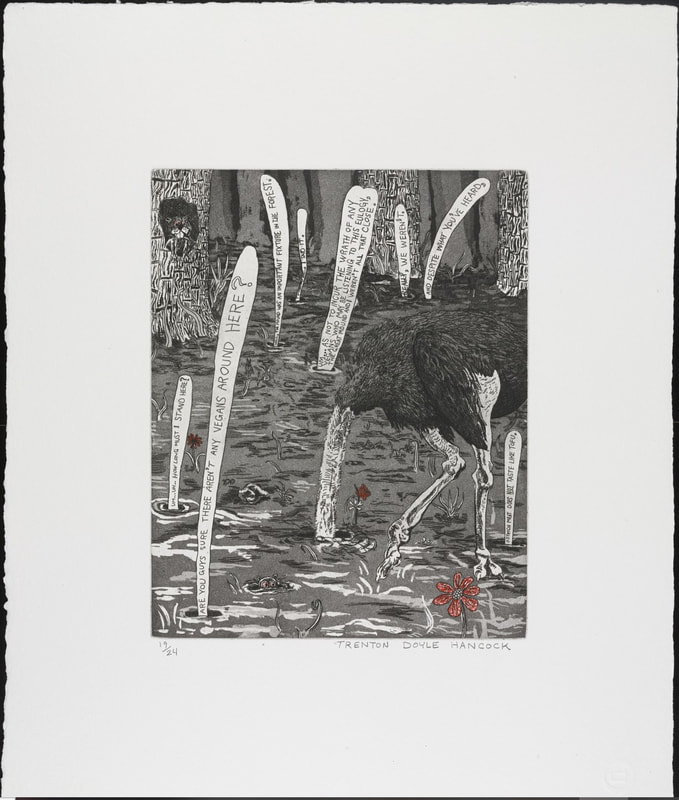

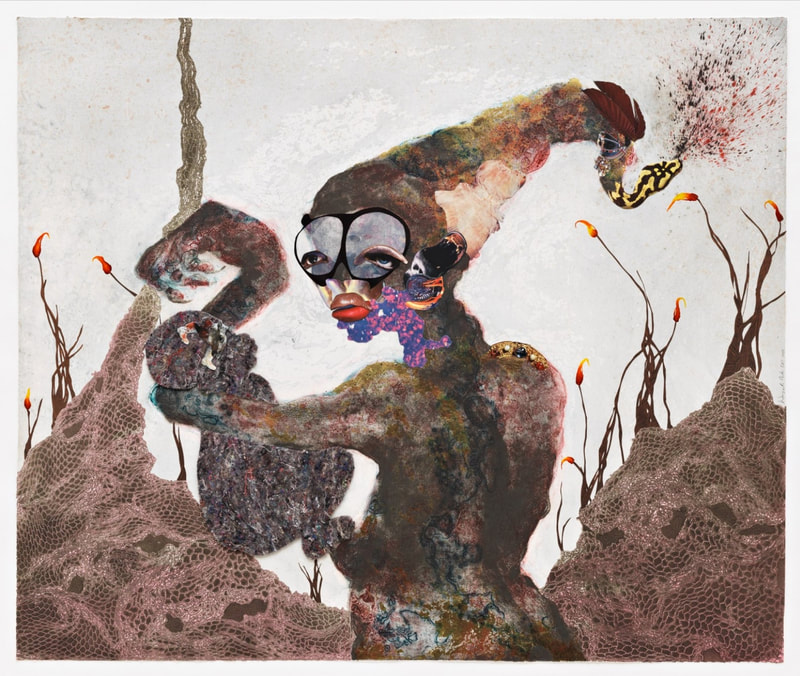

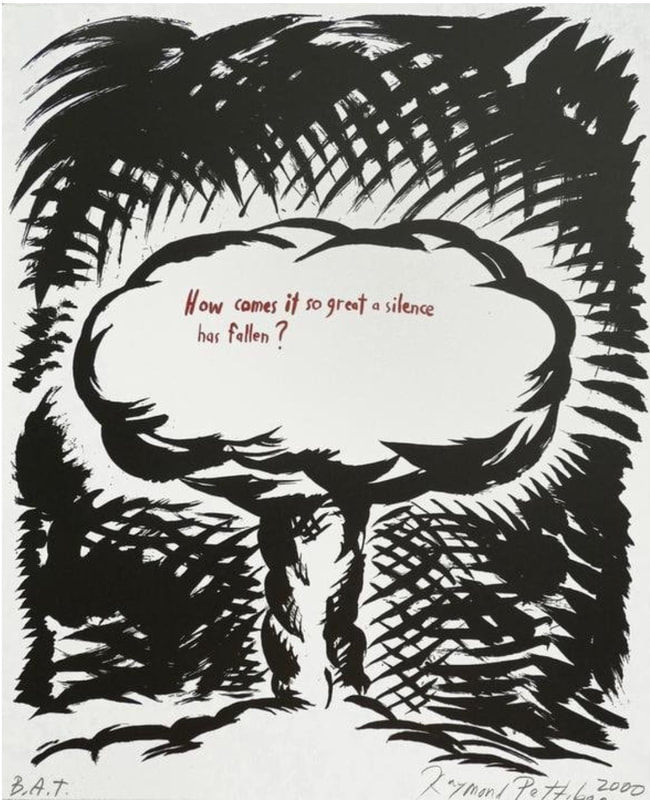

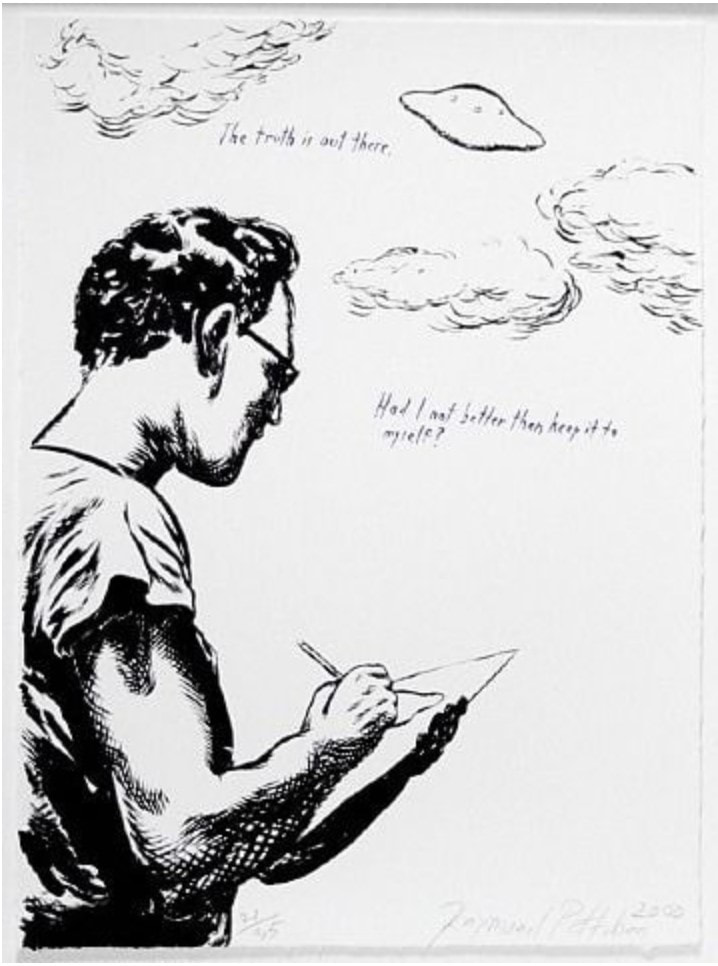

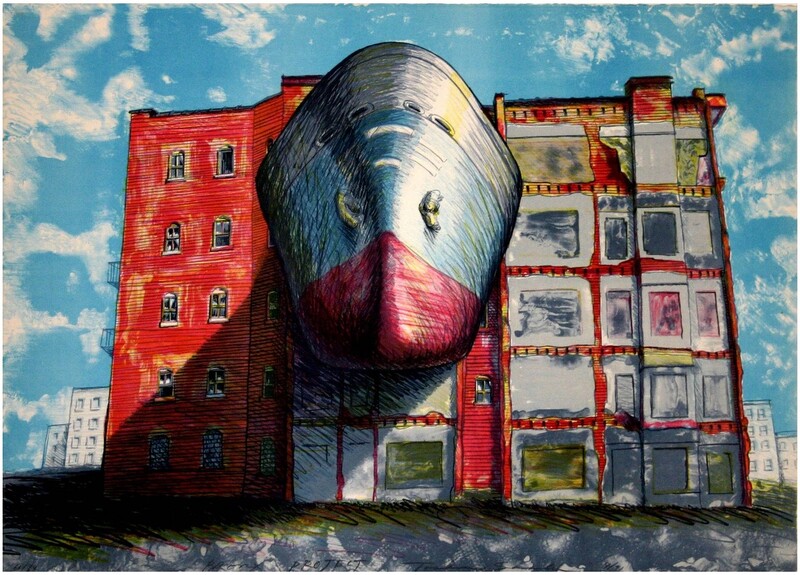

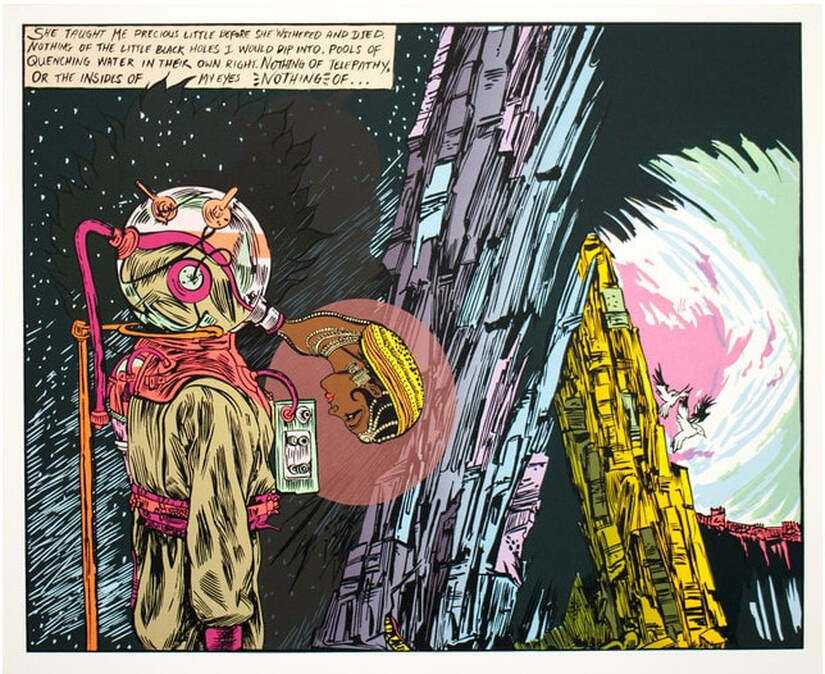

Alternate Realities included prints by iona rozeal brown, Amy Cutler, Chitra Ganesh, Wangechi Mutu, Toshio Sasaki, William Villalongo; portfolios by Trenton Doyle Hancock and Raymond Pettibon; and a book by Enrique Chagoya. The through-line of these works is that they are set in fictional (alternate) worlds and are extracted from personal narratives. The portrayed worlds are all quite different from each other, but within them these artists playfully exaggerate and reimagine the visual language of popular culture—religious stories, myths, and folk and fairy tales—as they consider larger societal issues. Through modes of picture making such as comics, street art, graffiti, and use of found images, these sometimes-humorous images rise above specific places and time to investigate issues of the human condition, cultural appropriation, gender roles, race issues, political protests, and other global issues. Most of the works were new to the collection at that point, meaning they came into the collection through purchases I made or through gifts I shepherded. I began seeking out these kinds of prints in response to requests I was getting from MICA students in the study room. They would come to see me with an assignment for their classes, which often consisted of studying one specific object for an extended period, drawing it, and then writing about it. After multiple requests to see something that reflected their interests in graffiti, zine culture, or comics, I realized we just didn’t have much to offer. The germ of an idea started with three objects already in the collection: Bye and Bye (9 sad etchings), 2002, by Trenton Doyle Hancock, Plots on Loan I, 2000, by Raymond Pettibon, and El Regreso del Caníbal Macrobiótico, 1998, by Enrique Chagoya. Slowly, over several years, I was able to acquire the remaining objects. Well, truth be told, the iona rozeal brown print was brought in by my colleague Rena Hoisington. The show came together is a magical way. I knew I wanted to be able to offer a show that would inspire those students who had asked if the museum had this kind of work. But the unanticipated consequence was that in pulling the works together, they ended up being by a rather organically diverse group of artists. By organic I mean I don’t think I could have planned it and succeeded. The other remarkable thing was the speed with which I was able to bring the show from idea to finished product on the wall. It’s super unusual to get new acquisitions out on view with any speed. Museums move like molasses in winter. Feedback on the show was very positive from the MICA students. I think they felt they were being heard, for once. And I was happy to oblige them. For all the times I emphasized how important it is to know who came before you—as Tru would say, upon whose shoulders you stand—I think it legitimized this mode of image-making for all those young artists. And for that I am truly pleased. Here is the label copy (with a few edits) that appeared on the walls of the exhibition. iona rozeal brown (American, born 1966) Untitled (Female), 2003 Published by Mueller Studios, New York Color screenprint BMA 2014.7 iona rozeal brown’s Untitled (Female) is a portrait of a geisha, a popular type of image found in woodblock prints from nineteenth-century Japan (see below); however, something is definitely different here. First, we notice the extra-large scale and brighter color palette of the twenty-first-century print. Even stranger is the dark brown tonality of the geisha’s skin, her peroxide-tipped dreadlocks, and her trendy Missoni-designed bikini top. This contemporary figure represents a sub-culture of Japanese teenagers known as Ganguro (which translates to “blackface”), who emulate African-American hip- hop style through dress, hair, and darkened skin. This sampling and remixing of cultural markers is in line with the artist’s own side-line as a hip-hop DJ. Enrique Chagoya (American, born Mexico, 1953) El Regreso del Caníbal Macrobiótico (The Return of the Macrobiotic Cannibal), 1998 Published by Shark’s Ink., Lyons, Colorado BMA 1999.113 Enrique Chagoya’s work addresses the complexity of cross-cultural identity and calls attention to the power relationships that exist when one culture is overcome or vanquished by another. This volume takes the form of a codex, a book form drawn from ancient Central American cultures. (Few examples of these Mayan and Aztec books remain since most were destroyed by Spanish conquistadors.) In The Return of the Macrobiotic Cannibal, Chagoya questions the structure of power and muses about how things would be different if the tables had been turned—that is, if Mesoamerica had been the dominant culture and had “cannibalized” the European culture and used it for its own purposes. Utilizing symbols pulled from ancient Mexican iconography, American popular culture, Christianity, and art history, Chagoya lets the conquered recast history on their own terms, serving up a smorgasbord of serious cultural critique heavily laced with satire. Amy Cutler (American, born 1974) Widow’s Peak, 2011 Published by Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Albuquerque, New Mexico Color lithograph BMA 2014.30 Mixing absurdity with whimsy, Amy Cutler creates surreal scenes that turn ideas about traditional women’s work on their head. In Widow’s Peak, women in old-world costumes have become the mountain peaks all while bearing goats on their backs. The goats attempt to direct the women forward by pulling on their braids. The setting, strung with prayer flags, is both dreamlike and inviting, and despite their burden, the women carry on with self-reliance and strength. Without an obvious narrative, Cutler leaves the significance of her image intentionally open-ended. However, the artist is known to be deeply concerned about the repression and oppression of women, which neglects that they are foundational. Chitra Ganesh (American, born 1975) Away from the Watcher, 2014 From the series Architects of the Future Published by Durham Press, Durham, Pennsylvania Color screenprint and woodcut BMA 2014.29 Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Chitra Ganesh is known for creating mysterious narratives inspired by comics and science fiction from both Western and Eastern traditions. By combining compositional elements, color, and text, she creates an otherworldly moment plucked out of an enigmatic narrative. This image raises many questions: Is somebody inside the scuba/space suit? Why does it appear to be propped up? Is the Indian goddess being expelled or inhaled? Are we are underwater or in outer space? What do the small-winged creatures signify? What calamity has befallen the city at right? The somber melancholy of the text seems at odds with the dynamic depiction of the planet’s fissures, as well as the brilliant color and energetic comic-book style representation. These alternate moods and narratives clash and connect in a newly constructed vision of the future. Trenton Doyle Hancock (American, born 1974) Bye and Bye (9 Sad Etchings), 2002 Co-published by Dunn & Brown Contemporary, Dallas, Texas, and James Cohan Gallery, New York Portfolio of nine etchings printed in black and red BMA 2003.35.1-9 Trenton Doyle Hancock is well known for envisioning and recounting an epic-sized saga of arch enemies, the peace-loving Mounds and evil Vegans. Over his career, Hancock has presented chapters of this twisted tale of good and evil in painting, sculpture, performance, drawing, and printmaking in a style melding comics, cartoons, and psychedelia. In Bye and Bye (9 Sad Etchings), the great and wise Mound Number One has died, and a lion, squirrel, elephant, shark, alligator, and ostrich have gathered to eulogize him. Wangechi Mutu (Kenyan, born 1972) Second Born, 2013 Published by Pace Editions, Inc., New York 24 kt gold, collagraph, relief, digital printing, collage, and hand coloring BMA 2014.8 Wangechi Mutu has lived and worked in Brooklyn, New York, since the 1990s. By combining hand drawing with collage elements, she creates powerful and deeply unsettling female figures that directly challenge ideas about contemporary consumption of the female African body. Set in a fantasy world that looks equal parts scorched earth, outer space, and aquarium, this oddly alluring mother and child dominate a landscape of fire-tipped weeds. Holding her child in the crook of her elbow, the mother twists her hand, which resembles a claw, over the child’s head. A snake seems to emerge from her hair, spitting sparks of fire or dirt. As we take in the strangeness of this figure, she seems to turn back and look at us, challenging us to enter her at once dreamlike and nightmarish realm. Raymond Pettibon (American, born 1957) Plots on Loan I, 2000 Co-published by Brooke Alexander, New York, and David Zwirner Gallery, New York Portfolio of ten color brush and tusche lithographs BMA 2000.56.1-10 Raymond Pettibon’s lithographs combine the satirical bent of political cartoons and the DIY aesthetic of zines, album covers, and underground comics. Pettibon marries each drawing with a brief text—often a fragment of a quotation taken out of context from nineteenth-century writers, such as Robert Louis Stevenson and Henry James. (Some texts are drawn from the writers’ personal letters, rather than from works of published literature.) Since the authors never intended their words to be associated with Pettibon’s images, the viewer is challenged to consider how word and image might be related, or what Pettibon might have had in mind when he put them together. Toshio Sasaki (Japanese, 1946–2007) Bronx Project, 1991 Published by Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Color offset lithograph Promised Gift of Darnell Burfoot Toshio Sasaki was a Japanese architect, who split his time between New York and his homeland. He is best known for his design submission for the World Trade Center memorial. (The project was ultimately awarded to another architect.) Here, the print shows the prow of a ship either attached to or breaking through the outer wall of a tenement in the Bronx. Perhaps it is a comment on the way domestic and industrial interests vie for space in one of the country’s most crowded cities. The print’s cartoon quality adds a touch of humor to a serious societal issue, enabling viewers to either engage with the growing problem or at least become aware of its existence. William Villalongo (American, born 1975) Through the Fire to the Limit, 2006 Published by Lower East Side Printshop, New York Color screenprint and archival inkjet print with collage elements BMA 2014.34 Brooklyn-based artist William Villalongo uses a cartoon and graffiti aesthetic to render Hurricane Katrina as a raging monster with teeth, tongue, and four enormous eyeballs. Even as black clouds move away and the brilliant blue sky appears, bright orange flames and a hand floating in the water tell of immeasurable damage to life and property. One wonders whether Villalongo’s Saturday-morning-cartoon style makes the disturbing image easier to digest, or if the tension between subject and technique heightens the viewer’s feelings of alarm and dread.

0 Comments

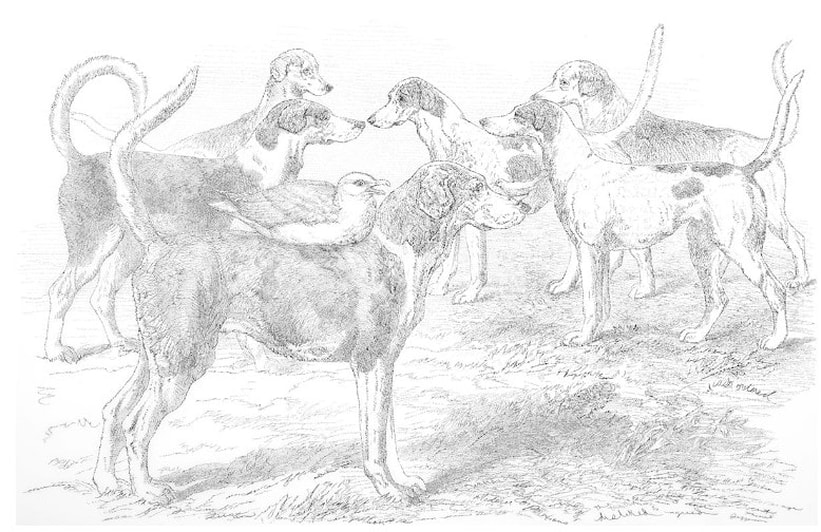

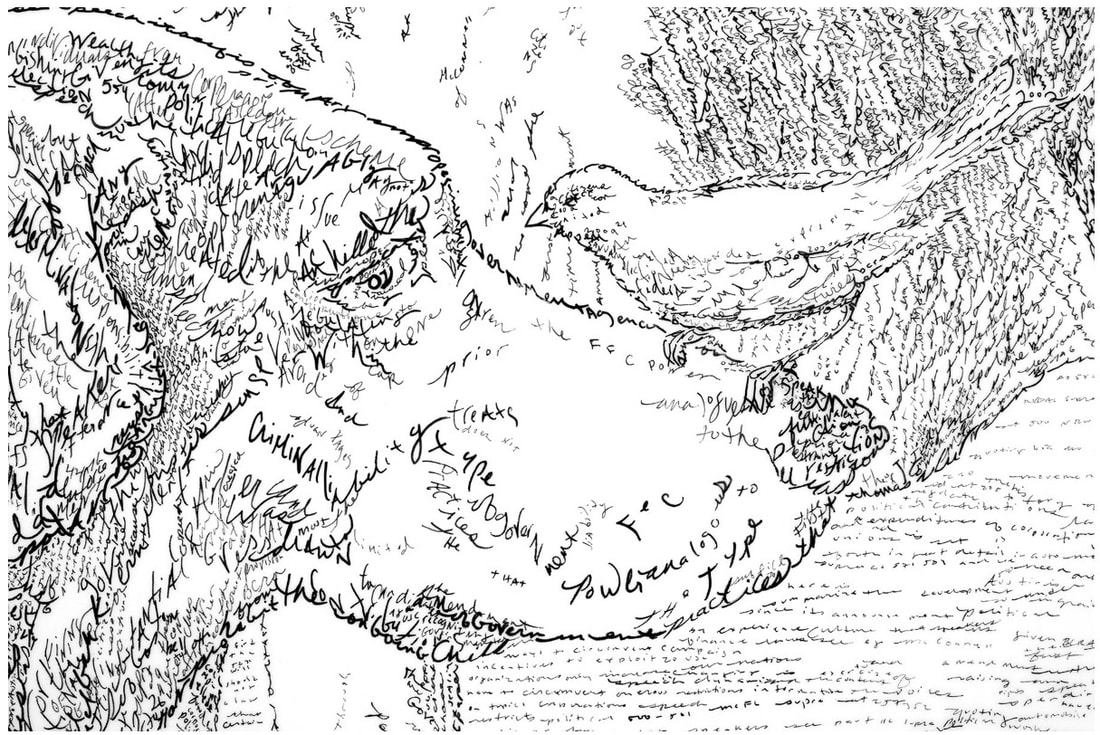

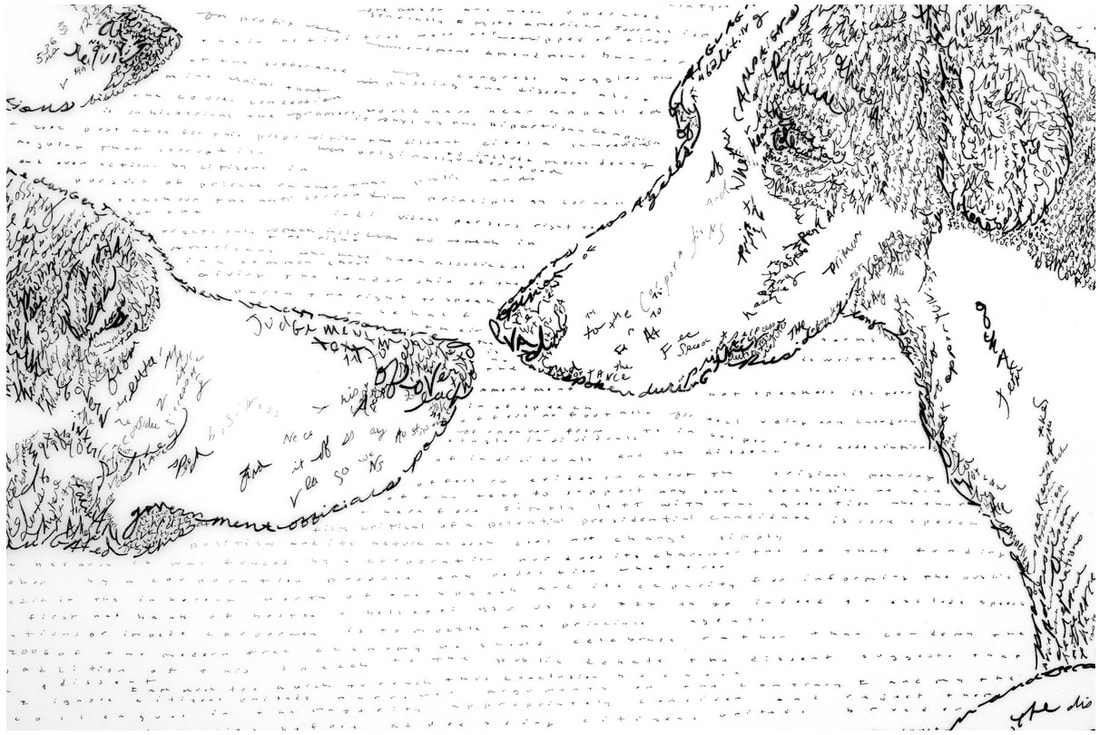

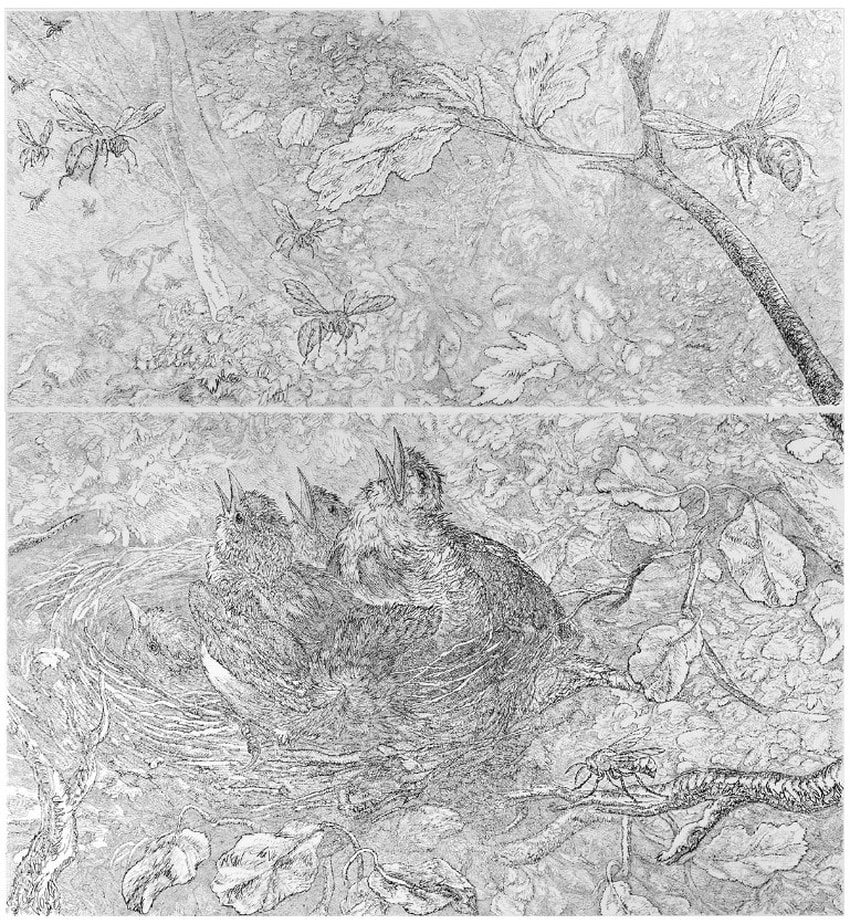

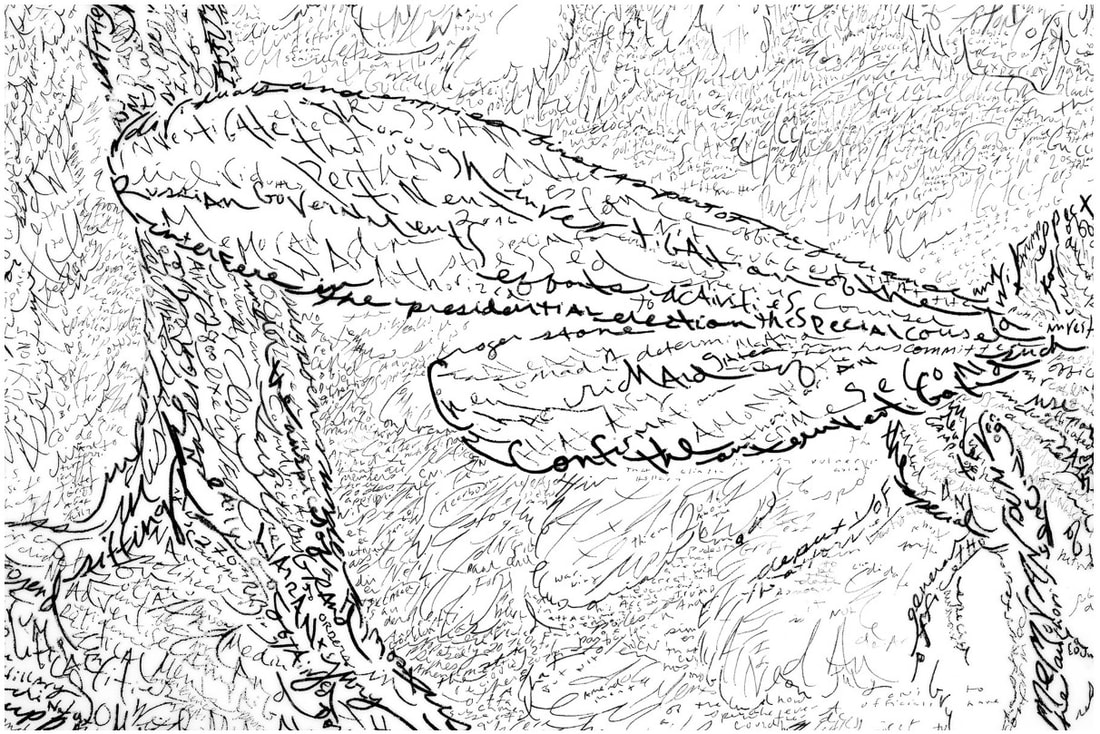

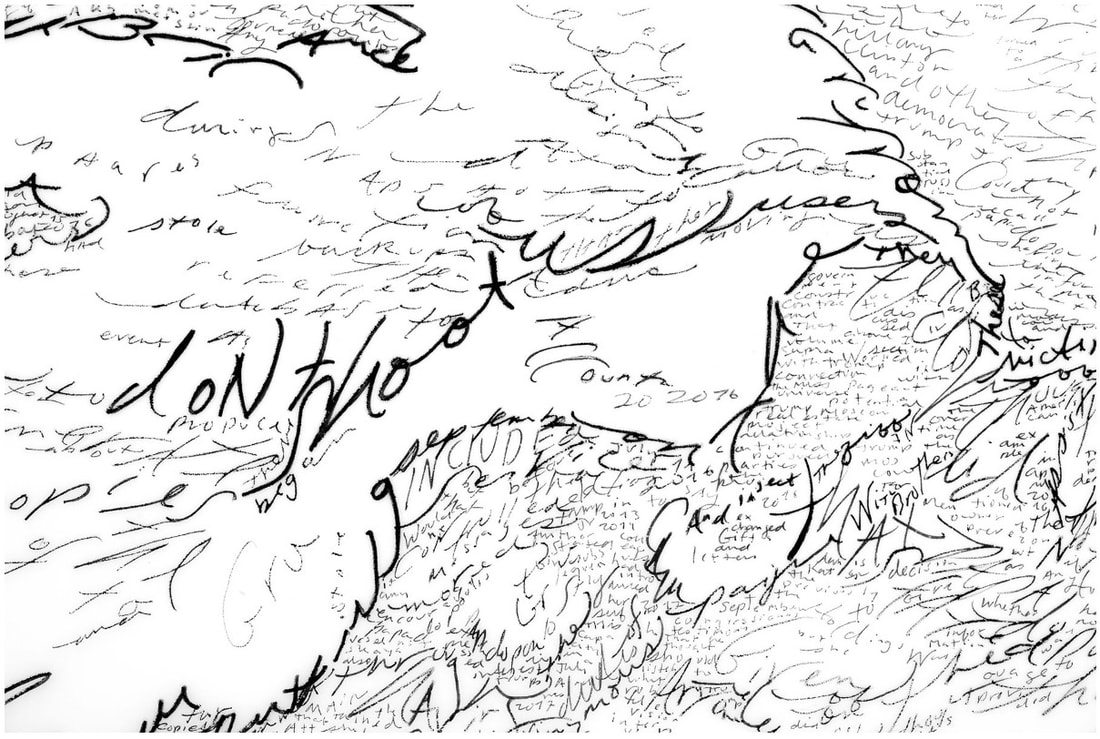

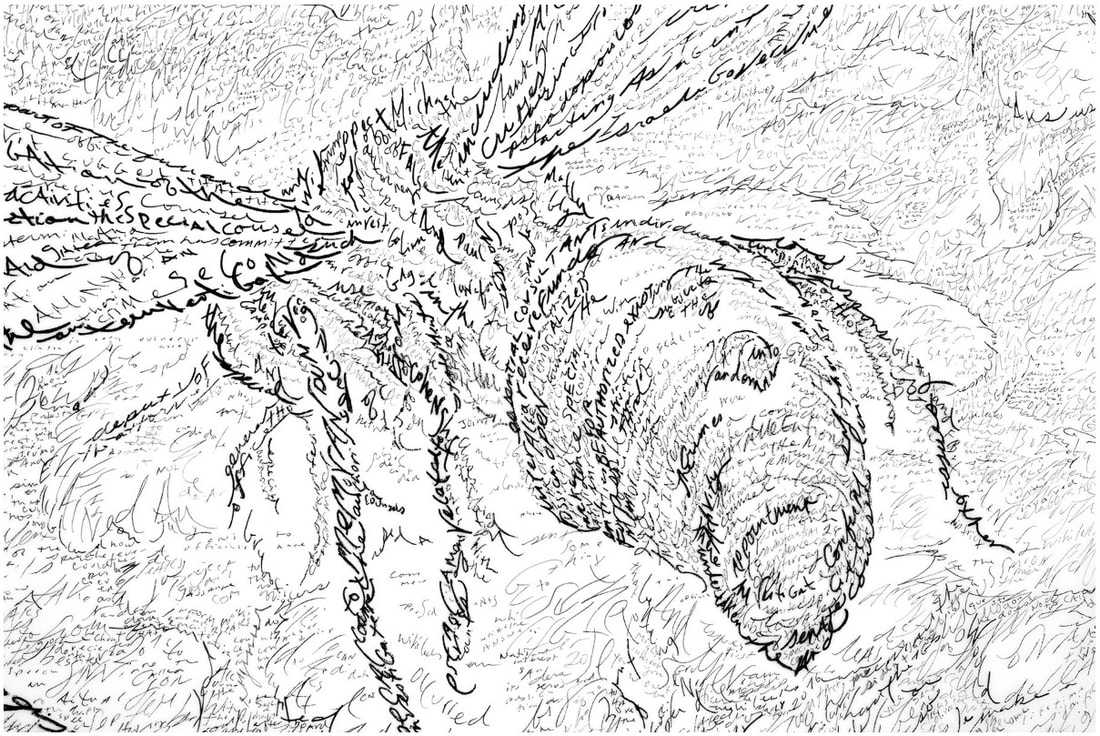

Ann ShaferFor the very first time since I left the museum three years ago (today is the anniversary), I am glad I’m not there anymore. The museum sector is going through some real come-to-Jesus moments. I am having a hard time watching from the sidelines and I can only imagine how frustrated I would be as a museum employee with little to no power to address the issues. Museums, by definition, are collections of things. Categorizing and defining objects and identifying the cultures from whence they came, as well as the notion of them as specimens for our study, has me feeling queasy. The whole enterprise has been rightly identified as a colonializing one. This idea isn’t new—I certainly didn’t come up with it—but at this moment, all these factors are colliding, and I am not sure I see a way for museums to come through it. What do you do when they are entirely based on the idea of studying the “other.” Is it possible to change courses to what necessarily has to be a wholly different model? Just what is the blueprint for this shift? I loved working in museums. I did it for nearly thirty years. I’m an object person. I believe art can help us think through difficult concepts as well as give us pleasure. I never wanted to do anything else besides create ways to tell interesting stories through great art. I love works that sit at the intersection of new and old, of abstract representation and representational abstraction, of beauty and toughness. Filed in the ones-that-got-away column is the work of Mike Waugh whose large-scale drawings demand attention. On the surface one sees an image that harkens back to traditional tropes of Americana: eagles, ducks, hounds, horses. One could write them off as illustrative and backward facing; but stay with it. Zoom in and notice each drawn line is really text. (This technique has a name: micrography.) These lines are not just random words selected because their shapes fit the bill, but words that together make up important political manifestos and bureaucratic documents. In a drawing from earlier this year, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, Waugh has written out the text of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling. Hugely controversial, it reversed campaign finance restrictions and enabled corporations and other groups to spend unlimited funds on elections. Reversing the one-hundred-year-old law allows wealthy donors, corporations, and special interest groups to have dramatically expanded influence on campaigns with negative repercussions for American democracy and the fight against political corruption. In Waugh’s image, a pack of hunting dogs are waiting for guidance—the blind leading the blind—while a seagull seated on one hound’s back seems to be anticipating the other shoe dropping. For Redacted, 2019, Waugh copied over 350 pages of The Mueller Report. It took months of meditative labor to accomplish the work (which is huge for a drawing at some 6 x 6 feet). A nest of baby birds with mouths agape are innocently stuck in the nest until they gain maturity. For the moment they are just waiting to be fed and hoping for the best. Wasps swarm above them menacingly. While the Mueller Report laid out definitive evidence of corruption and criminal activity within the 2016 Trump election campaign, the populace is unable to take really meaningful action (until November 3, that is). Politically charged content and “traditional” imagery intersect here. The beauty and intricacy of the drawings engages us. Understanding what the text says and represents gives us pause. Artists are always interested in getting people to linger longer over their work, and Waugh’s delicate, massive, impactful drawings richly reward scrutiny. Michael Waugh (American, born 1967) Citizens United, 2020 Pen and black ink on Mylar 45 x 69 inches (114.3 x 175.3 cm) Courtesy Von Lintel Gallery Michael Waugh (American, born 1967) Redacted (The Mueller Report, volume I & II), 2019 Diptych, pen and black ink on Mylar Overall: 81 x 76 inches (206 x 193 cm.) Courtesy Von Lintel Gallery Ann ShaferWhen the museum acquired Chitra Ganesh’s work, I already had the seed of a show growing in my mind. I had been asked to come up with an exhibition drawn from the collection featuring works by artists of color. This is problematic on many levels. I have always believed that separation is sometimes useful, but that integration must be the goal. In any case, the works available for a show of that sort lacked any thematic cohesion. At the same time, I’d had many MICA students inquire about seeing works from the storeroom that reflected a graffiti or comic book sensibility. The collection did not have much to offer. It took time and several acquisitions to bring together an exhibition that focused on the theme of alternate realities—artists looking at real-world problems through visual fantasies, comics, sci-fi. Ganesh’s gorgeous print fit the bill beautifully and was installed along with prints by Trenton Doyle Hancock, Wangechi Mutu, Toshio Sasaki, Enrique Chagoya, William Villalongo, iona rozeal brown, Raymond Pettibon, and Amy Cutler. On Paper: Alternate Realities was on view September 21, 2014–April 12, 2015. It was the most organically diverse show of my career and remains one about which I feel extremely proud.

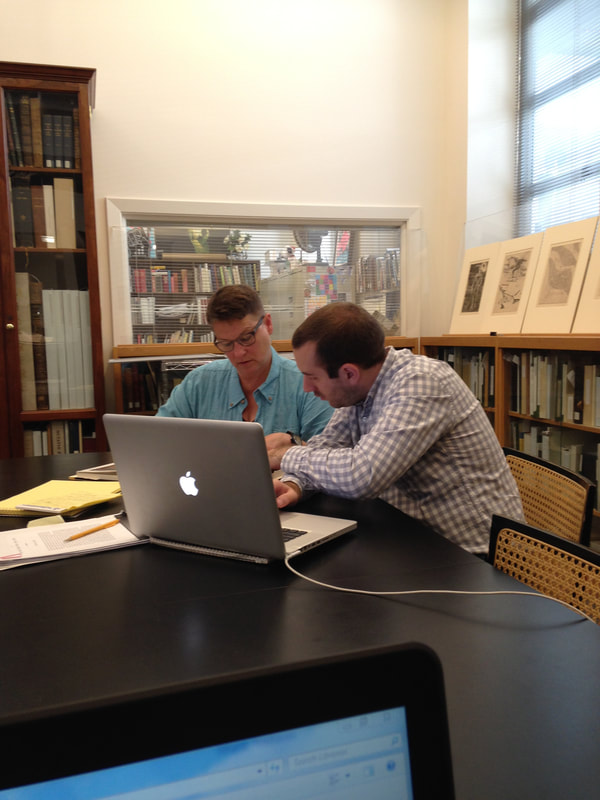

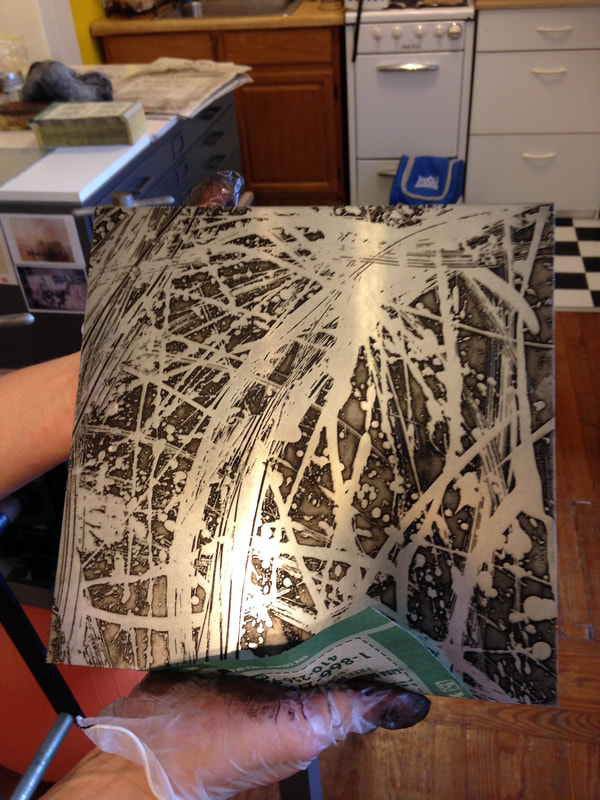

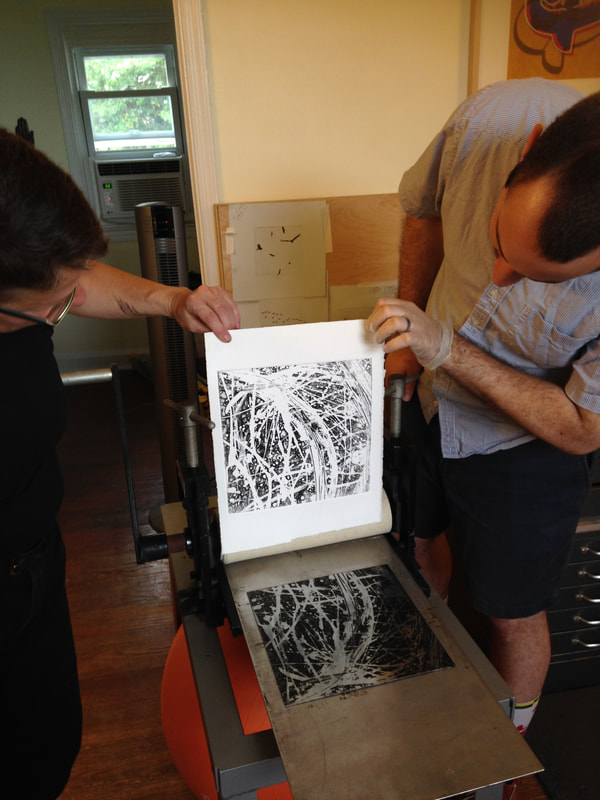

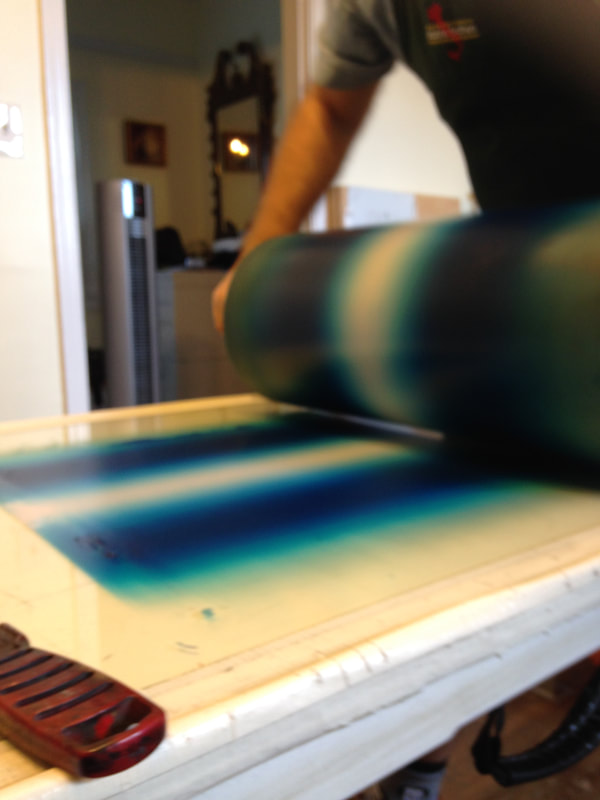

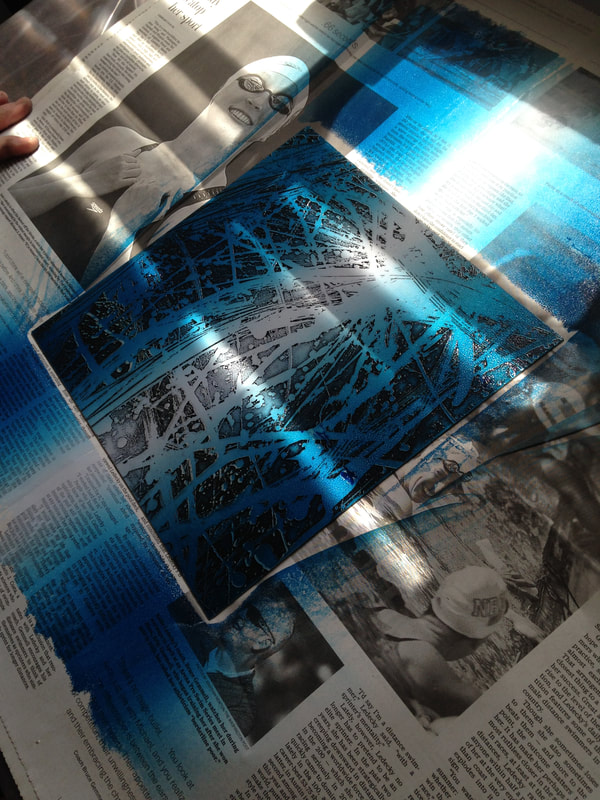

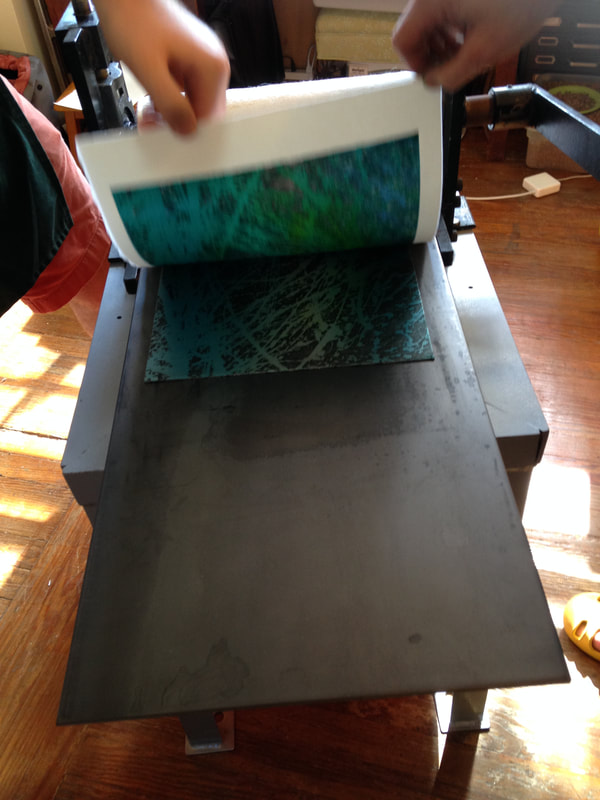

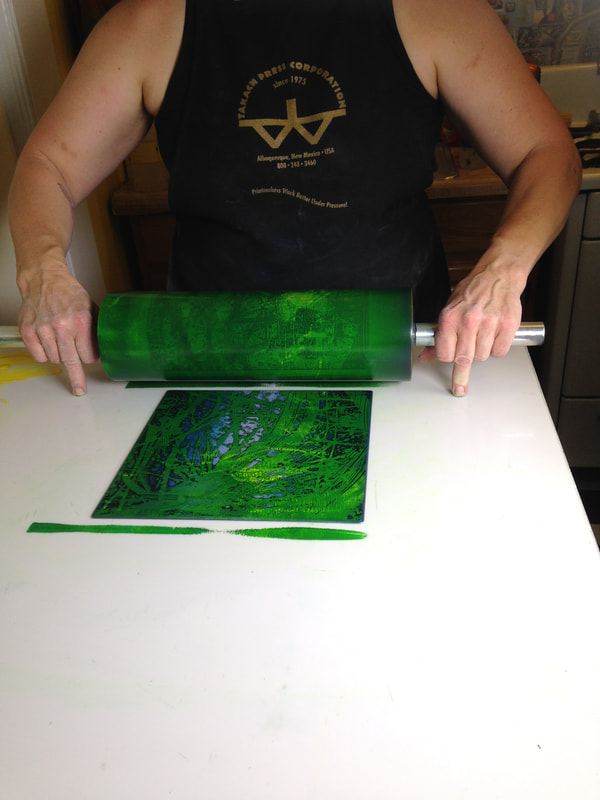

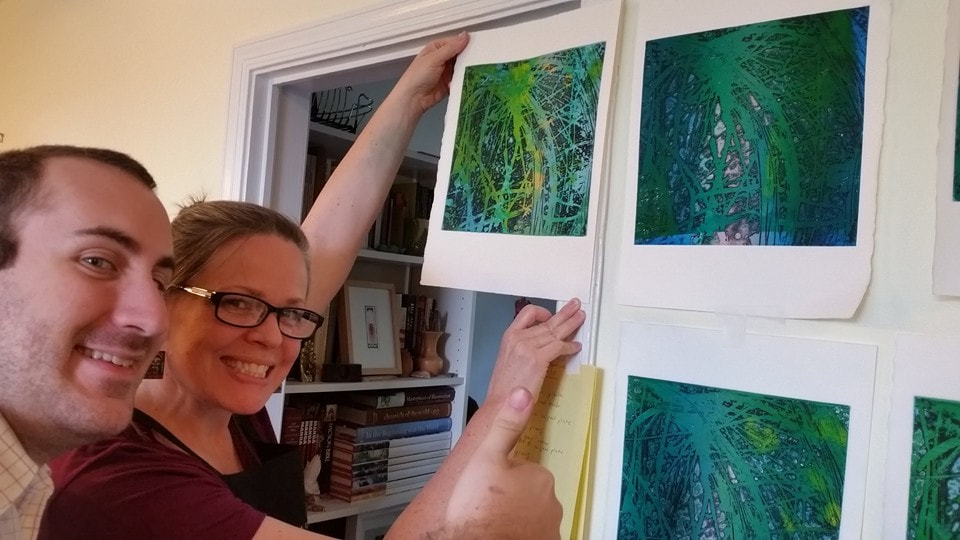

I love a print that looks cool and asks more questions than it answers. Chitra Ganesh’s Away from the Watcher is a colorful combination of screenprint and woodcut that features an enigmatic figure at left (in a scuba or space suit—you decide) who seems to be exhaling an Indian goddess figure, while watching a city on a hill possibly being destroyed. Along the top left is a comic-strip-style thought bubble that reads: “She taught me precious little before she withered and died. Nothing of the little black holes I would dip into. Nothing of telepathy, nor the insides of my eyes. Nothing of…” This image raises many questions: Is somebody inside the scuba/space suit—isn’t it propped up? Is the Indian goddess figure being expelled or inhaled? Are we underwater or in outer space? What do the small winged creatures signify? What calamity has befallen the city at right? The somber melancholy of the text seems at odds with the dynamic depiction of the planet’s fissures, as well as the brilliant color and energetic comic-book style of representation. These alternate moods and narratives clash and connect in a newly constructed vision of the future. Chitra Ganesh (American, born 1975) Printed and published by Durham Press Away from the Watcher, 2014 From the series Architects of the Future Woodblock and screenprint 629 × 797 mm. (24 3/4 × 31 3/8 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of an Anonymous Donor, BMA 2014.29 Ann ShaferIn my previous post I talked about Stanley William Hayter's 1959 open bite etching Cascade and promised to dig into its making. It takes many images to describe the process of simultaneous color printing, so I created a PDF slide deck to illustrate how Ben Levy, Tru Ludwig, and I made a group of test prints to figure it all out. You can find the PDF here:

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed