Ann Shafer The Big Bang. How do you express the formation of the planet and its inhabitants, and what kind of craziness had to come together to create the elements that, put together, make humans capable of thought, creativity, love? It’s really all dumb luck, isn’t it?

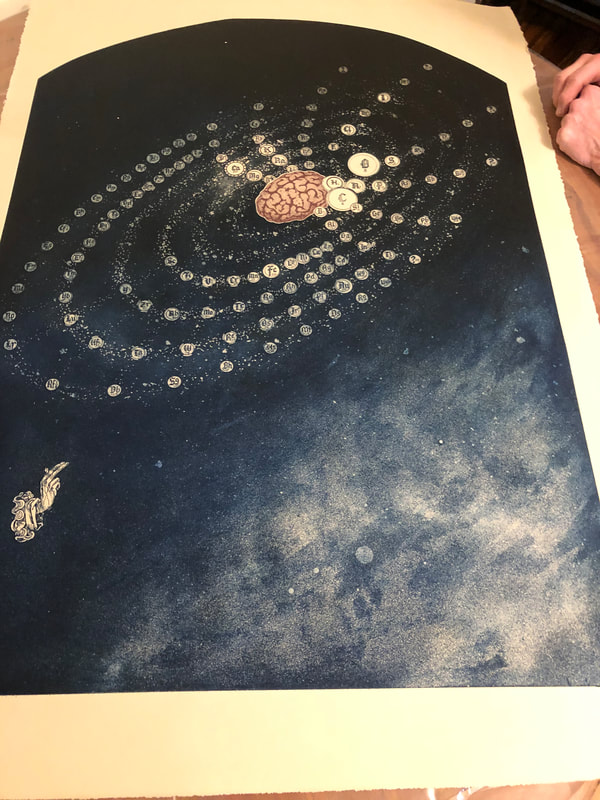

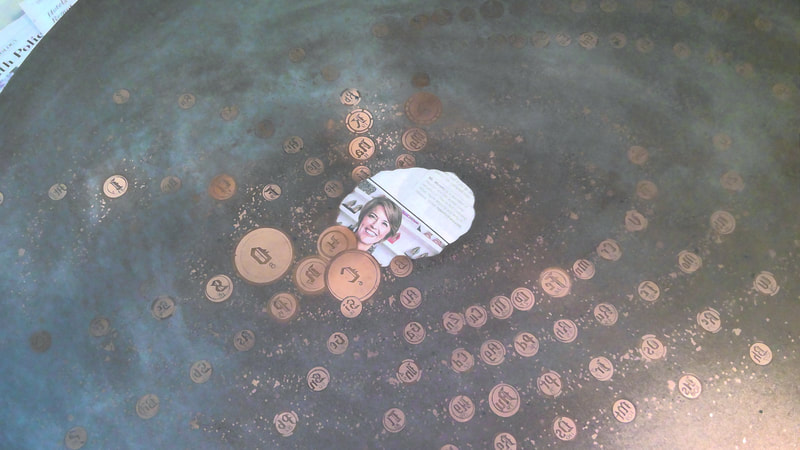

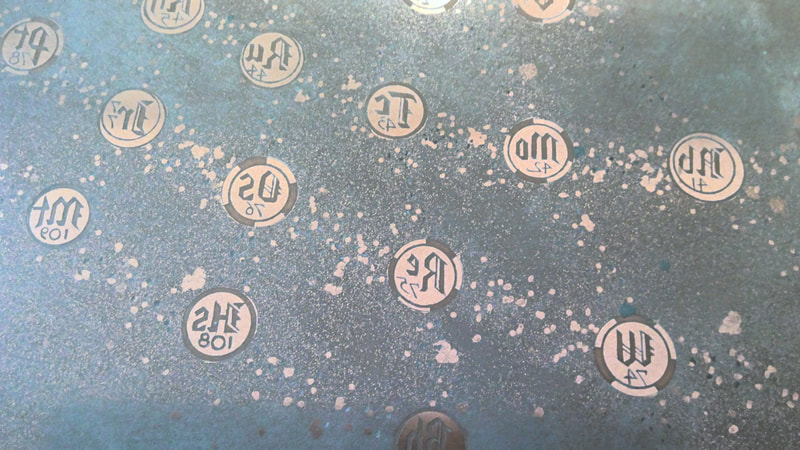

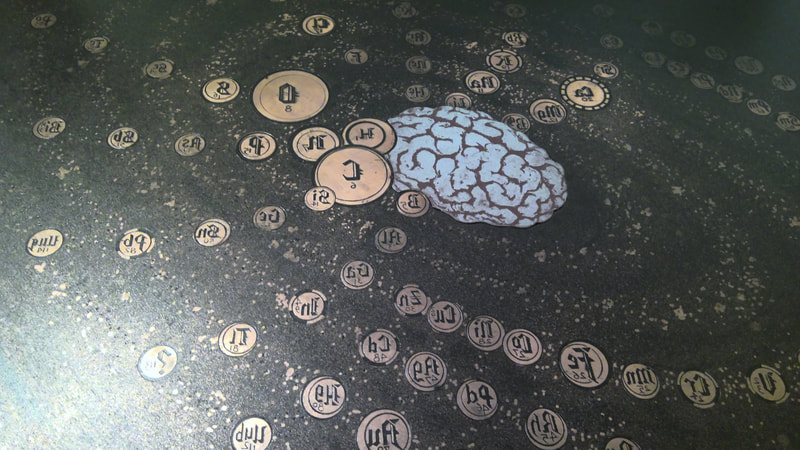

I recently helped Tru Ludwig print a rather large etching tackling this concept, Dumb Luck, 2009. The composition is a ring of periodic table elements swirling around a human brain set against a galaxy of stars. That brain is a zinc plate cut to fit into the center of the copper plate. The image is printed in blue-black (on the copper plate) and deep red (on the zinc plate). Scribing the element symbols took Tru three months to complete. I believe it. They are intricate, delicate discs floating on an aquatinted galaxy of stars and planets. Three bright white, far-off stars are drilled holes in the plate that carry no ink. They are a small yet vital part of the composition. Then there is a set of blessing hands at lower left. So, in addition to pondering the dumb luck that enables our existence, it raises questions about whether a higher power had a hand in our design. I love this print. I’ve always loved looking at pictures of the stars and galaxies and I’ve always been amazed by the Big Bang theory. How could it be that all this was created without some sort of intentionality? I’m not a particularly religious person, but it does make one wonder. That Tru figured out a way to convey this mystery astounds me. You may recall that Tru and I printed another of his prints, Ask Not…, last weekend, during which I was sort of helpful. I think I graduated to really helpful printing Dumb Luck. By the end of the session, I was wiping that little brain without supervision. I was wiping those element discs. I even came up with a method of quickly removing the first layer of ink—I’m pretty proud of that. We fell into the print-shop ballet that will be familiar to anyone who prints. I loved being in the studio and it reignited my long-held desire to open a print shop and publish prints. If only I would win the lottery in order to be able to do so. <sigh>

0 Comments

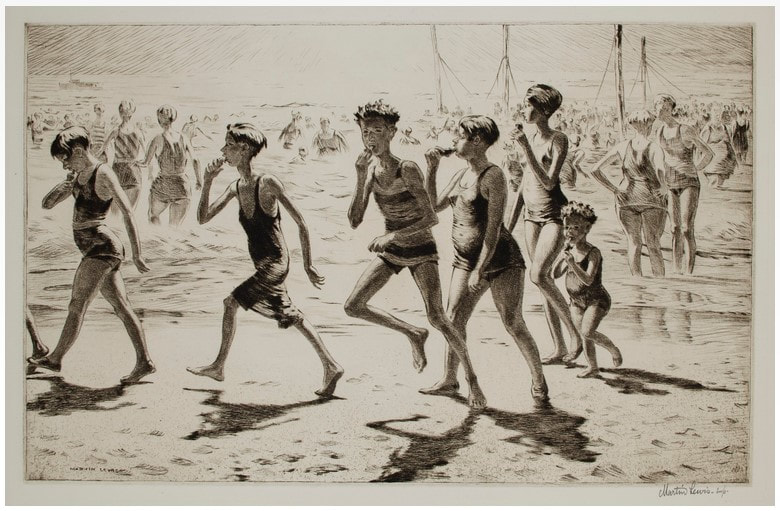

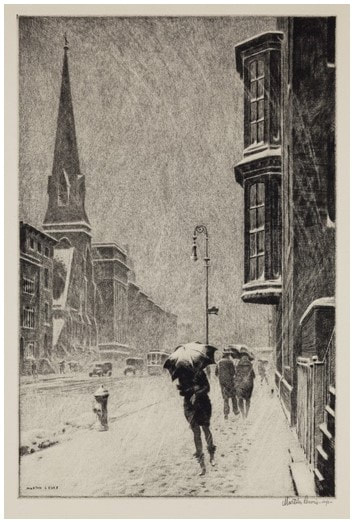

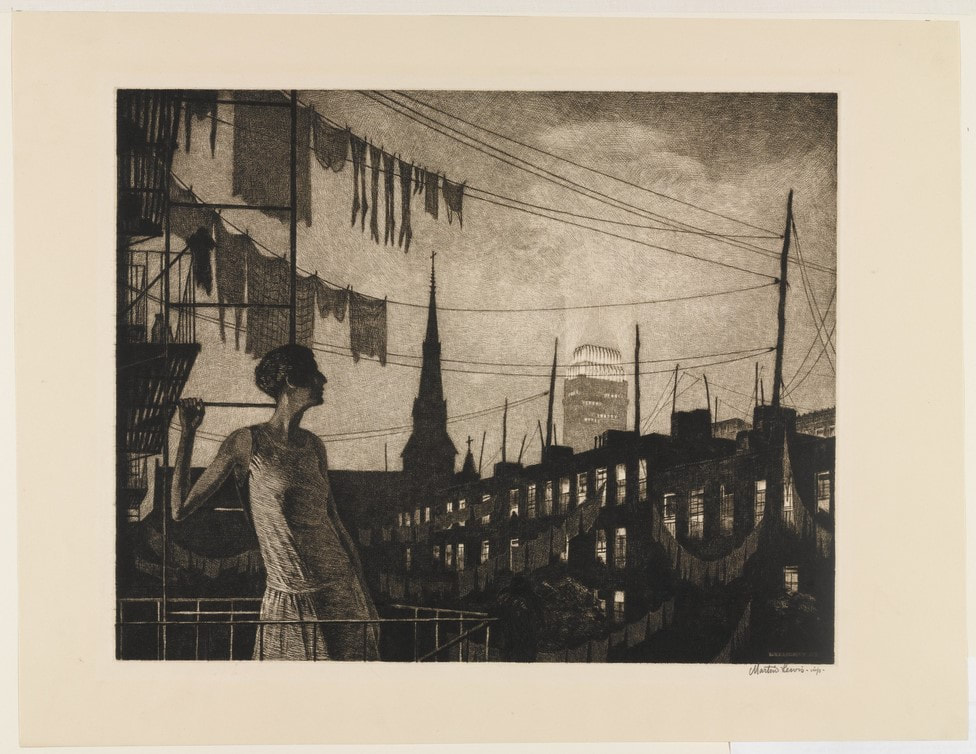

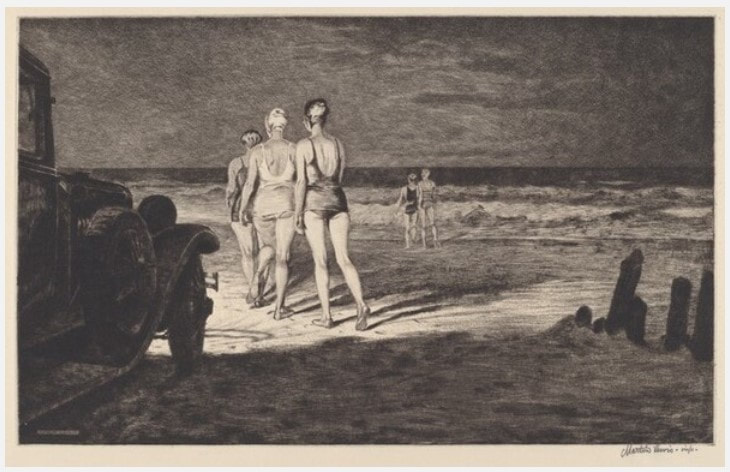

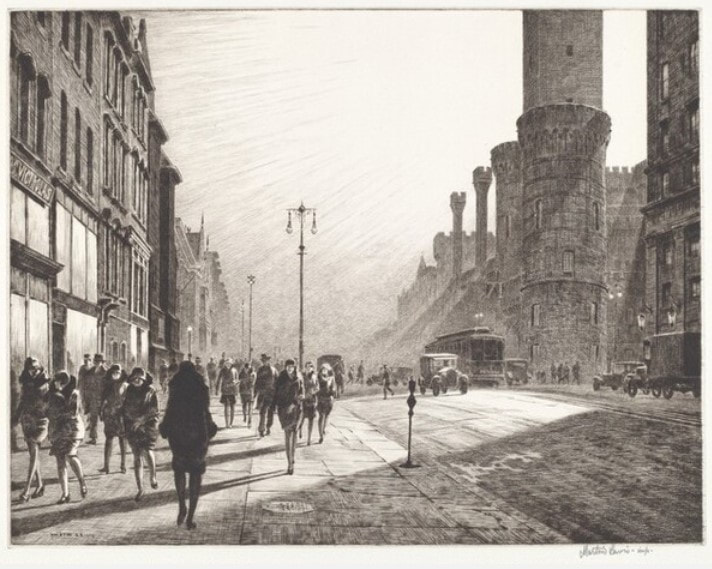

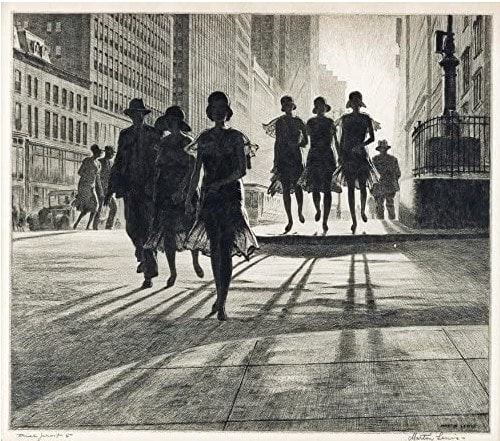

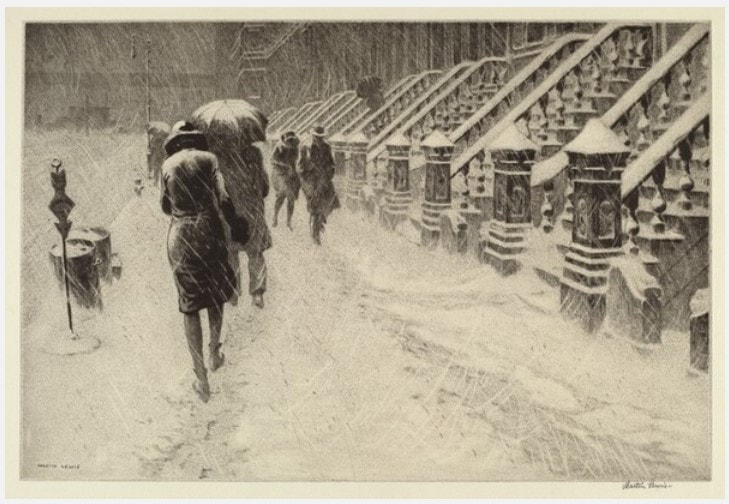

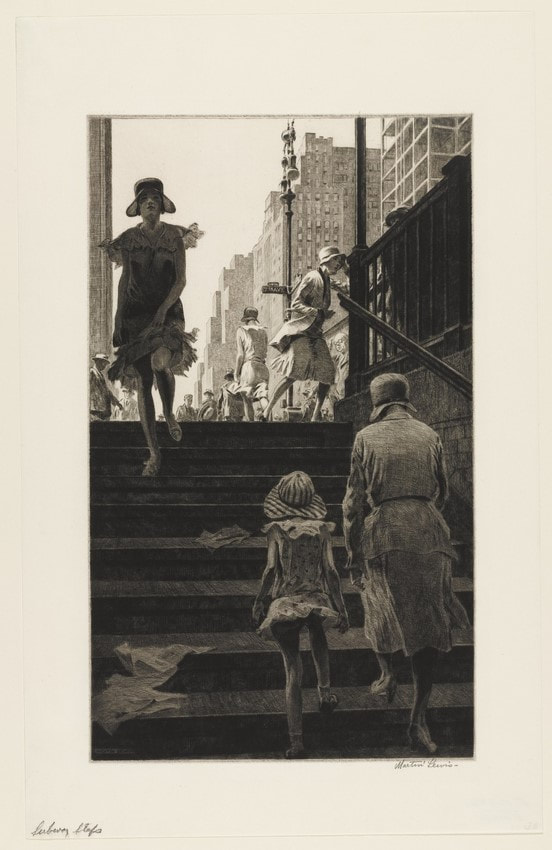

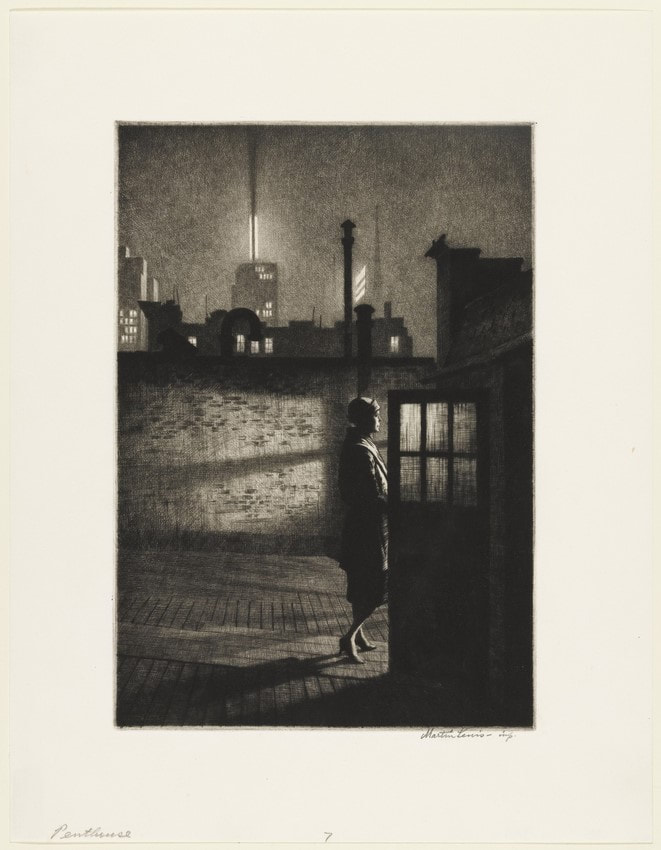

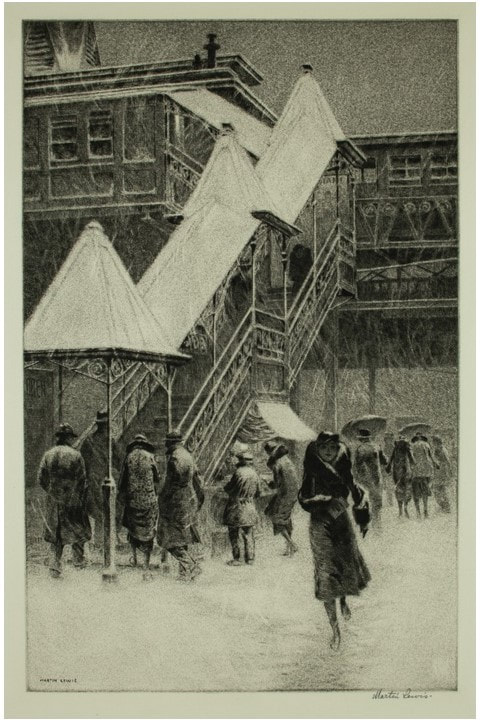

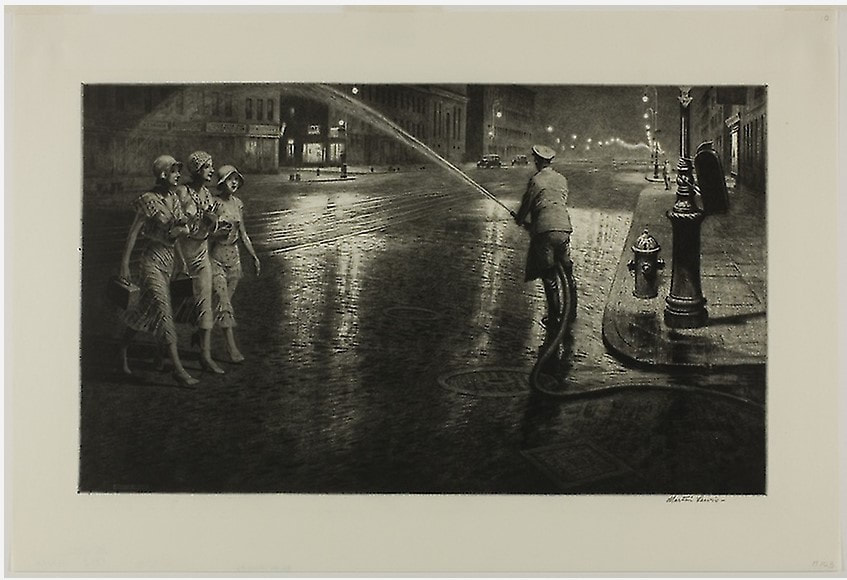

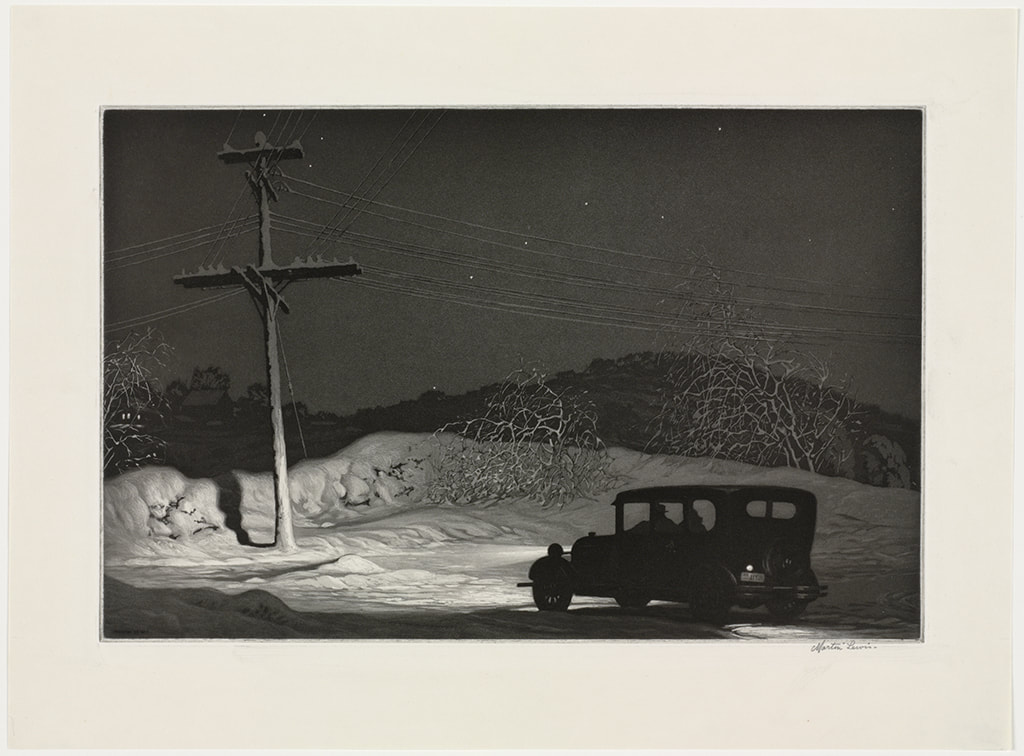

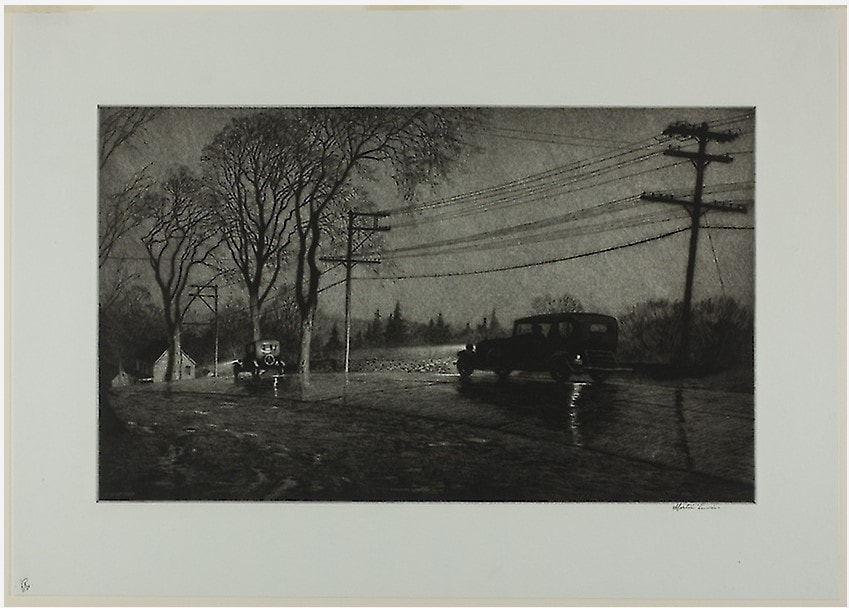

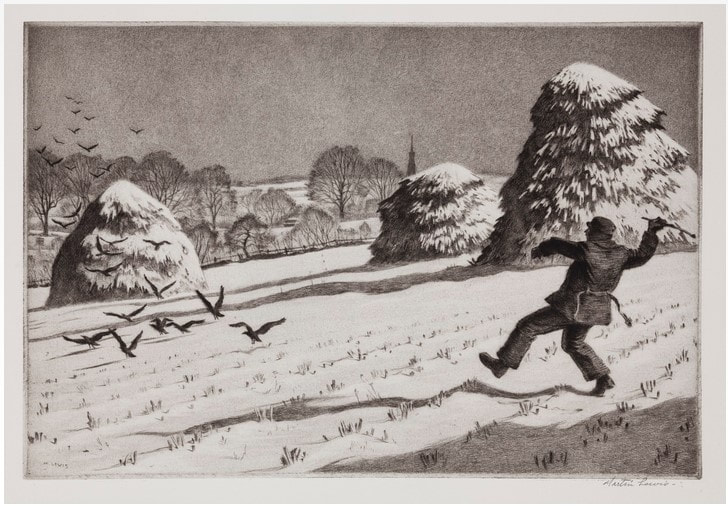

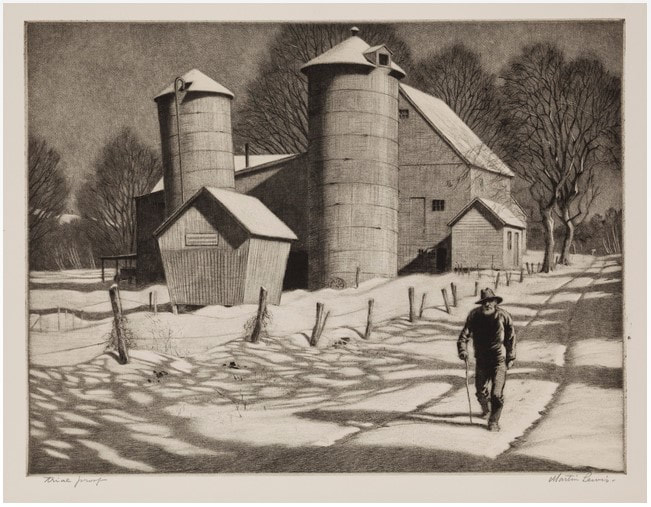

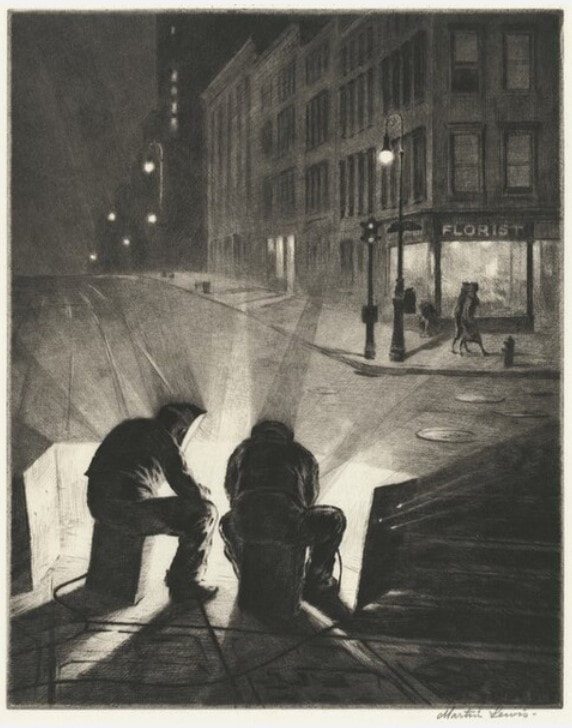

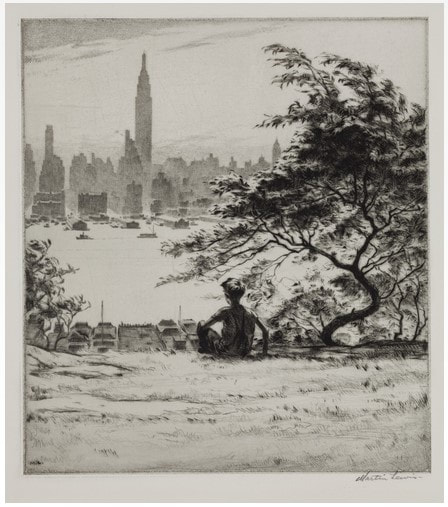

Ann Shafer I’ve loved Martin Lewis’ etchings and drypoints of urban and rural scenes from the 1920s and 1930s since I tripped over an impression of Shadow Dance in a solander box at the museum. That print’s light, the shadows, the translucency of the dresses, and the composition are soooo good. And that’s a self-portrait—the man on the left is Lewis himself. His prints would feature prominently in my imagined exhibition City/Country.

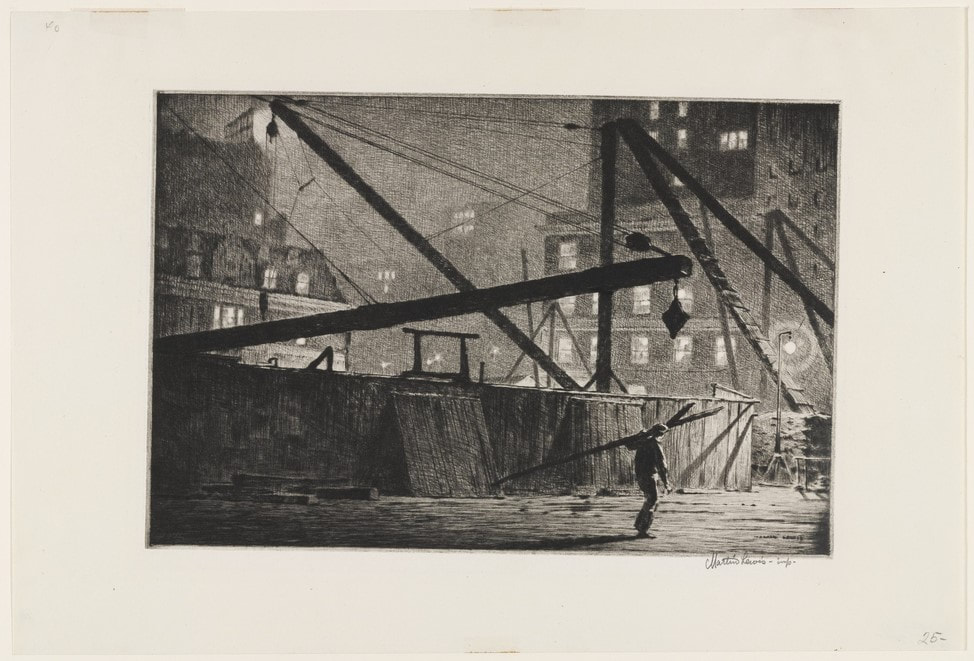

Maybe I’m drawn to Lewis’ work because of my time in New York as a young professional. I mean, I never walked to the Whitney in heels and a flapper dress with a cloche hat, but I did hoof it across town in a suit and white sneakers, work shoes tucked in my oversized purse. Of course, I was blasting some good eighties ballads on my Walkman—Paul Young, anyone? I was young and had recently discovered that I wanted nothing else than to be a curator. I was full of hope for my future and was thrilled to be living in the Big Apple. Living in New York, with its water towers, brownstones, skyscrapers, parks, yellow cabs, and subways made me appreciate the urbanism popularized by Alfred Stieglitz and his stable of early-twentieth-century artists. The Whitney’s permanent collection cemented my love for them. There were gorgeous paintings hanging on the third floor of the Whitney’s Breuer building including canvases by Georgia O’Keeffe, Joseph Stella, Charles Sheeler, and my two first loves, Charles Demuth and Edward Hopper. Demuth’s My Egypt and Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning were pilgrimage stops for me when I wandered the galleries before opening. Lewis may not be as well-known as other artists working in New York in the first half of the century, but his prints are worth a look. Plus, he is credited for introducing Hopper to printmaking—the two remained lifelong friends. Both these artists’ print prices are sky high now, and it always makes me laugh when these prints have original prices scrawled on them: $25 or even $15 (see Derricks at Night--$25 is marked at lower right). Wouldn’t it have been nice to reward the artists with today’s prices during their lifetimes? Lewis was born in 1881 in Victoria, Australia. As a youth, Lewis worked on cattle ranches in the Australian Outback, in logging and mining camps, and as a sailor. In 1898, he moved to Sydney and studied art for two years (his only formal training). It is unclear if he learned printmaking in Sydney, although we do know a local radical paper, The Bulletin, published two of his drawings. In 1900, Lewis arrived in San Francisco and made his way to New York shortly thereafter. Like many other artists, Lewis made his living as a commercial artist. He produced his first etching in 1915 and soon taught Hopper how to make them. In 1920, Lewis used his entire savings to travel to Japan to study and make art. After two years there, he returned New York and resumed his commercial art career, while also making his own paintings and prints. From 1944–1952 Lewis taught a graphics course at the Art Students League. Over thirty years, Lewis made some 145 drypoints and etchings. His prints, like Shadow Dance and Stoops in Snow, were admired during the 1930s for their realistic portrayal of daily life. (Remember there was still a divide between artists who worked in an “American style” versus European Modernism.) Call me a fan. I love Lewis’ compositions, the range of lights and darks, the transparencies, the “alone in a crowd”-ness of them. If only we could afford them. See what you think. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed