Ann ShaferI’ve been thinking a lot about why I feel compelled to write posts about art. Since I am no longer at a museum, and because of these crazy and scary times—we just hit that unfathomable milestone of 100K dead—I wanted to get some stuff down for the record. A blog seem like a good method to share some thoughts.

This pandemic has brought into the light so many cracks in our society. How we come through the other side remains to be seen. There are many things that I hope will change, and many institutions that I hope will survive. I think writing about art takes me away to somewhere beautiful, thoughtful, hopeful. It all takes me back to why I was drawn to art history in the first place. It is a truth that understanding history is critical for humankind’s survival; it’s crucial to understand where we’ve been in order to move forward with hindsight's wisdom. When I was in school, history classes consisted of a straight-up recounting of politics, governments, and wars. While important, those things felt pretty far away, and I confess to feeling a combination of boredom and depression. (Acknowledging privilege here.) It always felt like there had to be more. More information about hopeful aspects of human life. More information about society and how culture is key and revelatory. More about things that closely impact our individual and personal lives. In art history I found a recounting of human history through the perspective of art and culture. Rather than the contentious and divisive world of politics and warfare, culture and art offer hopeful, uplifting perspectives and still convey our history. Aha! And yet, throughout thirty years in the art business, I periodically had a crisis of faith. It sometimes seemed like art was an unnecessary and frivolous aspect of society, the proverbial icing on the cake. Nice to have, but not essential. But I have come to believe that art is a critical component in our lives. (Let’s not forget to mention the economics of this robust sector. It may not be the best paying of careers, but there are many, many people engaged in this important work.) Further, I believe that creativity is the best part of being human. I believe that artists are uniquely suited to create art that not only pleases the eye but also challenges the mind. It is a higher-order type of thinking and is unique to humans. It would be sad indeed if we were to squander this amazing ability, but embracing it fully gives me hope for our future. The possibilities for impacting lives are endless. For me, it is an honor to help people understand art a bit better. And I hope that my passion for it is infectious. Image: Ann Shafer giving a talk to the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society of the Baltimore Museum of Art in March 2013. Photo credit: Ben Levy

0 Comments

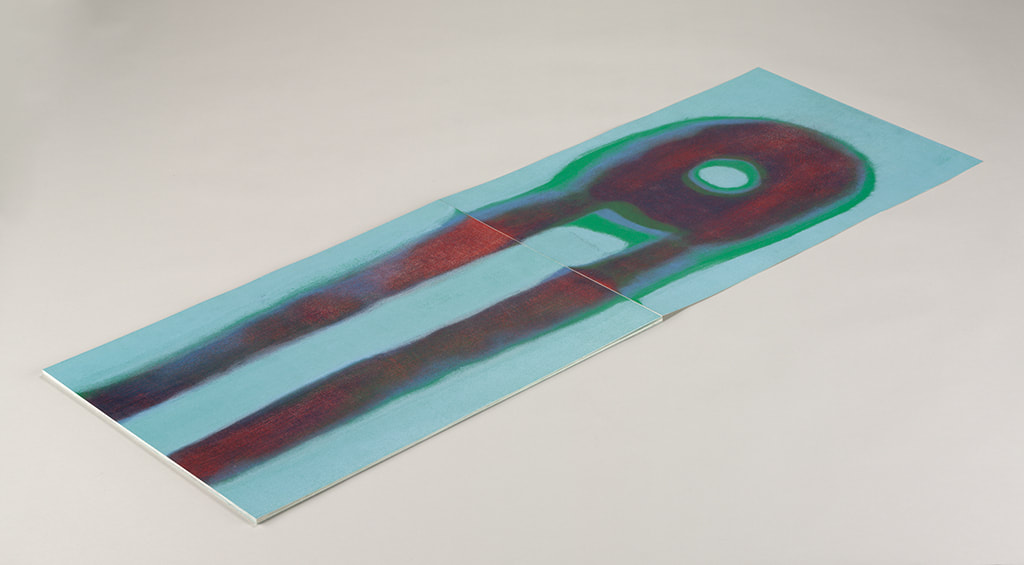

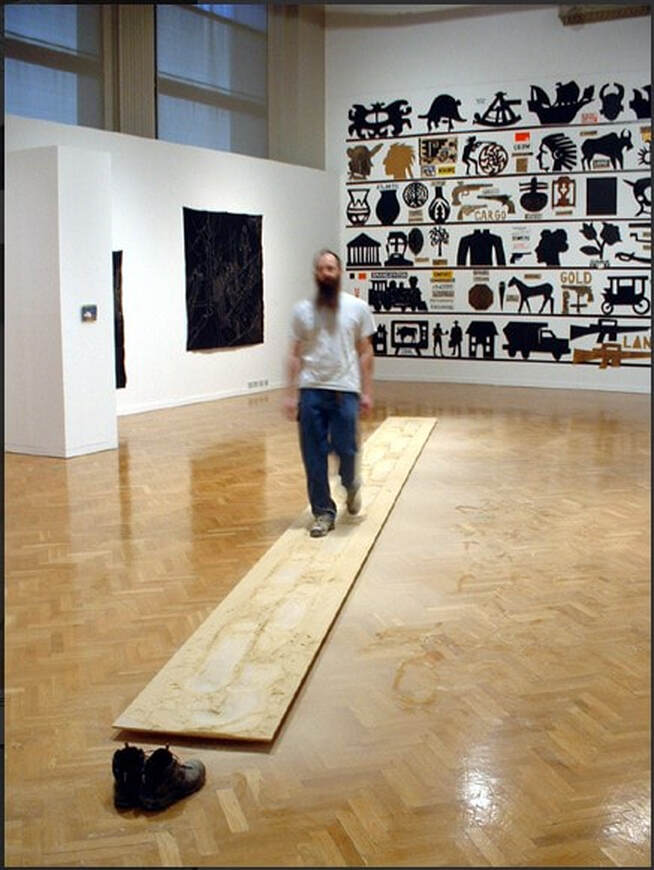

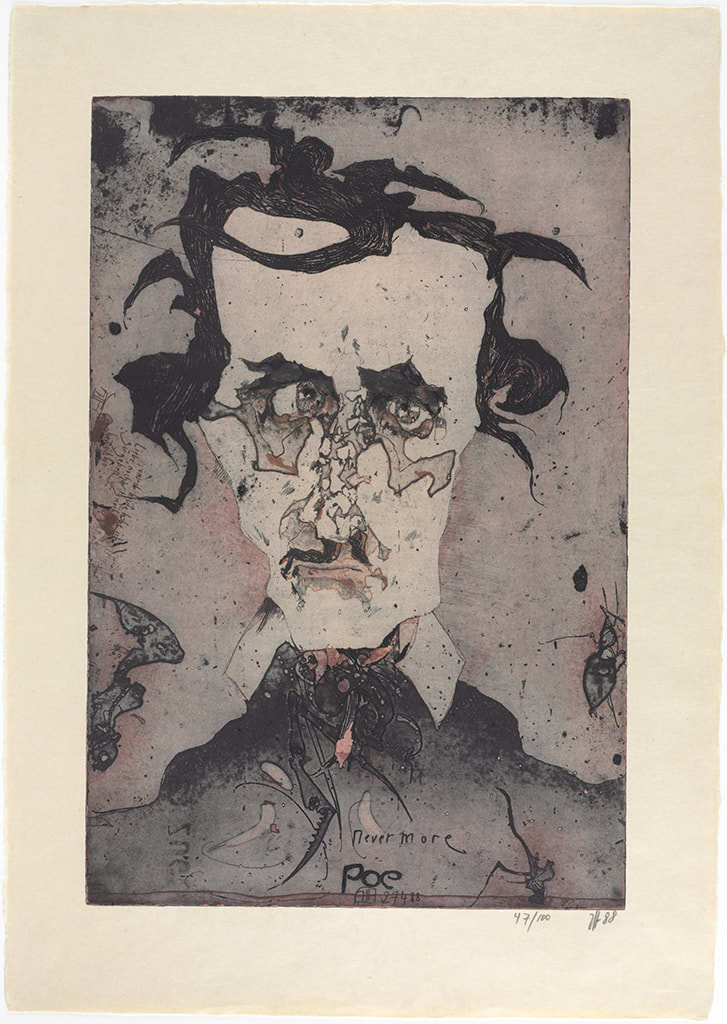

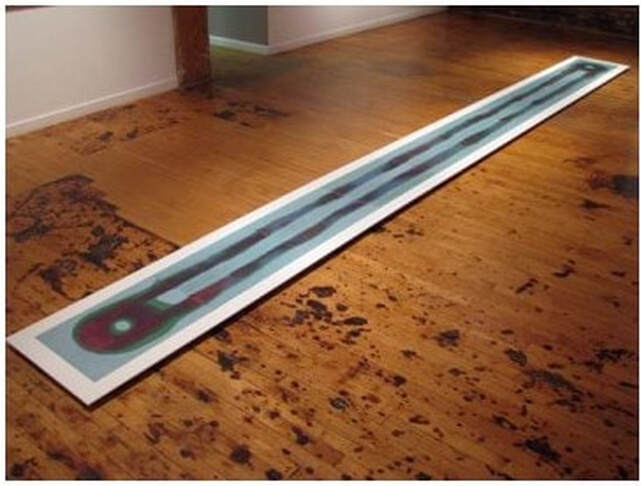

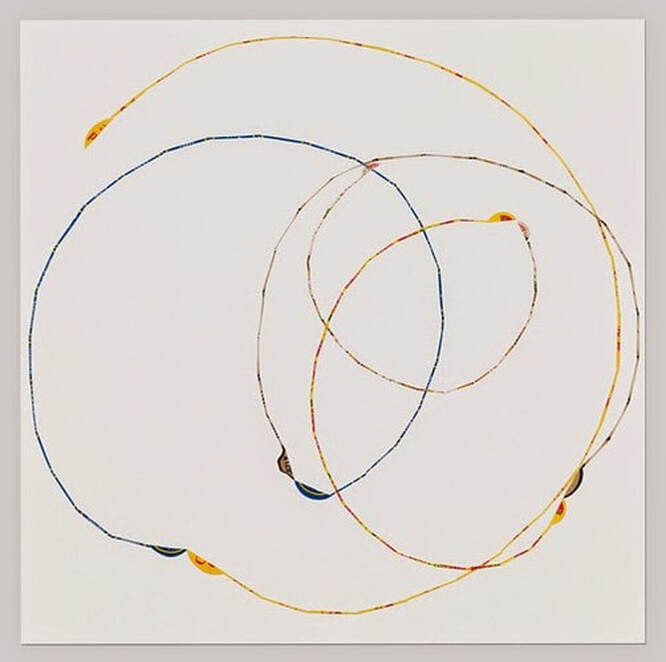

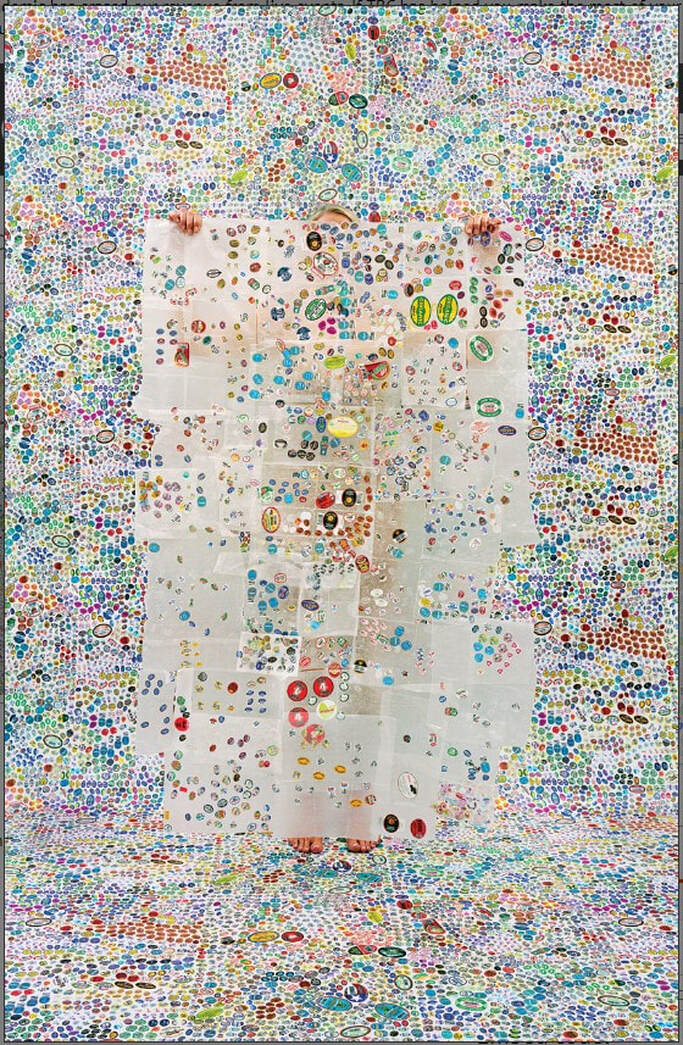

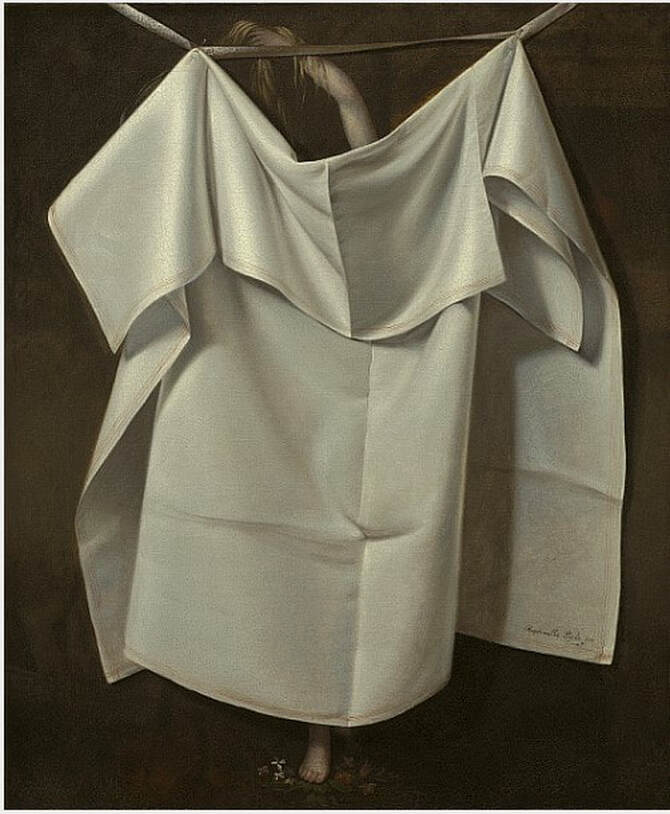

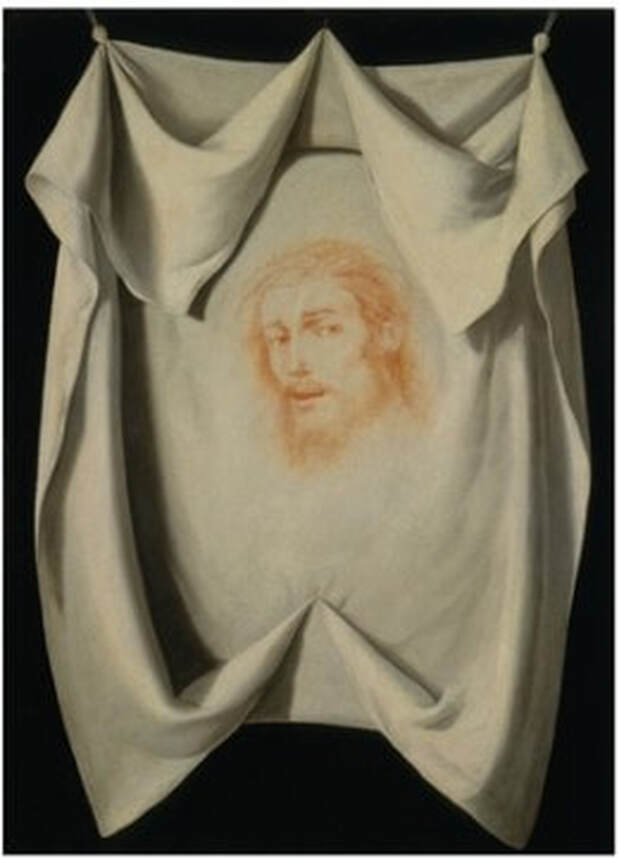

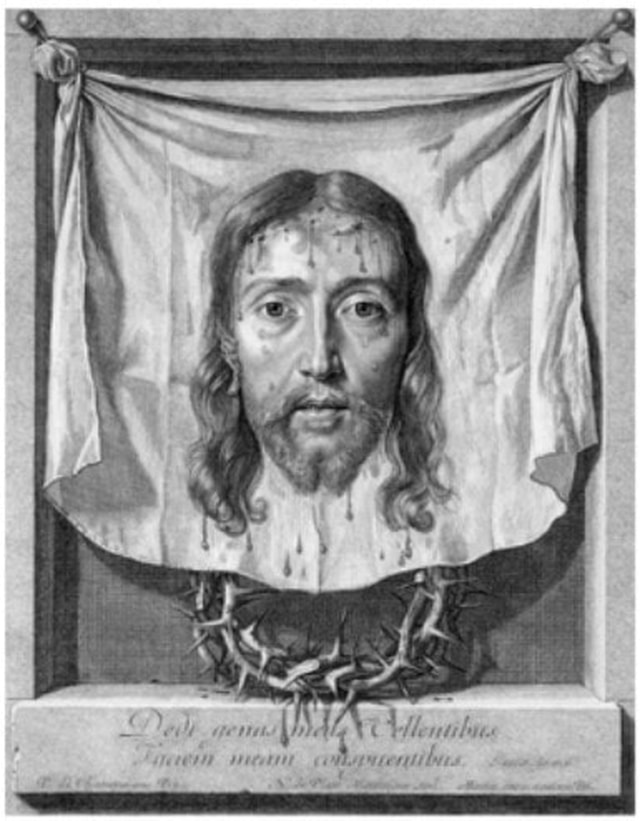

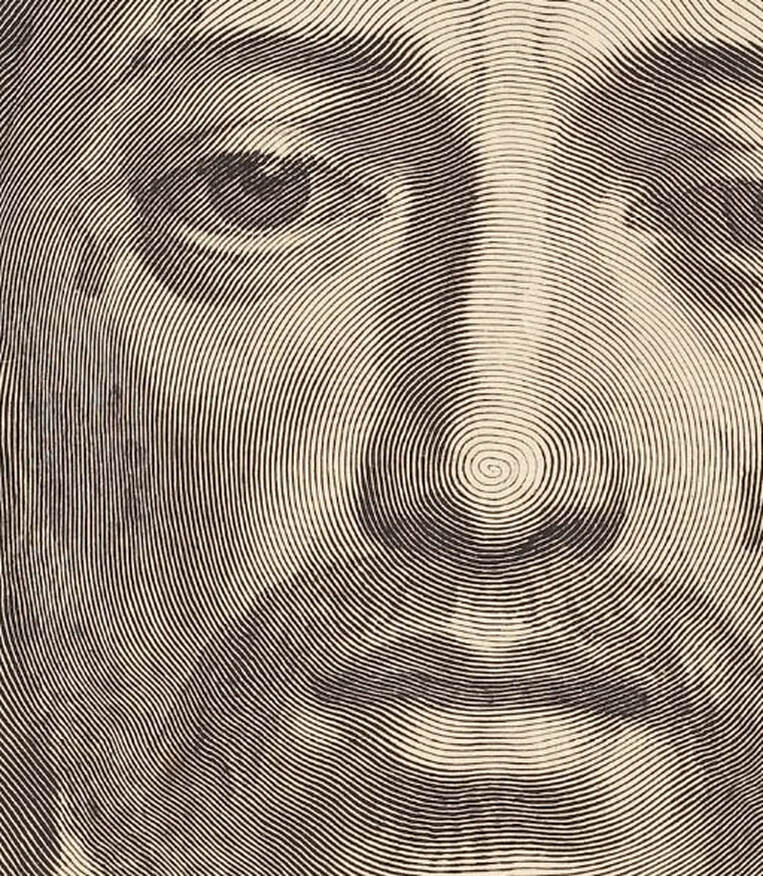

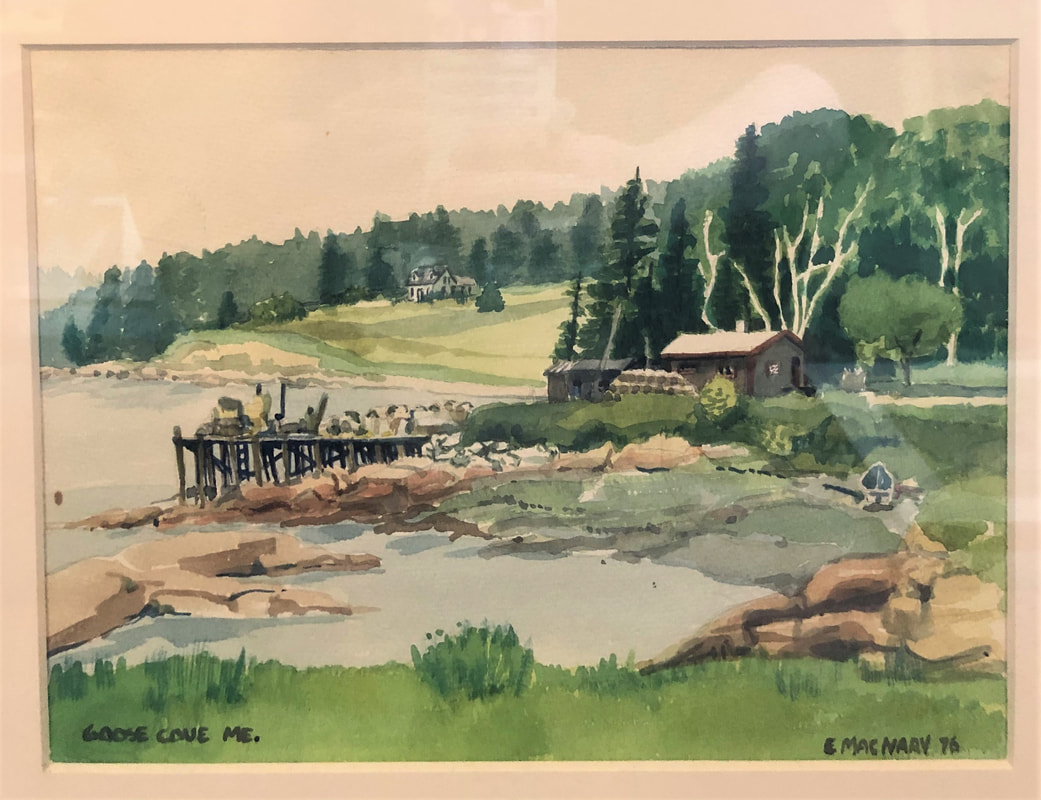

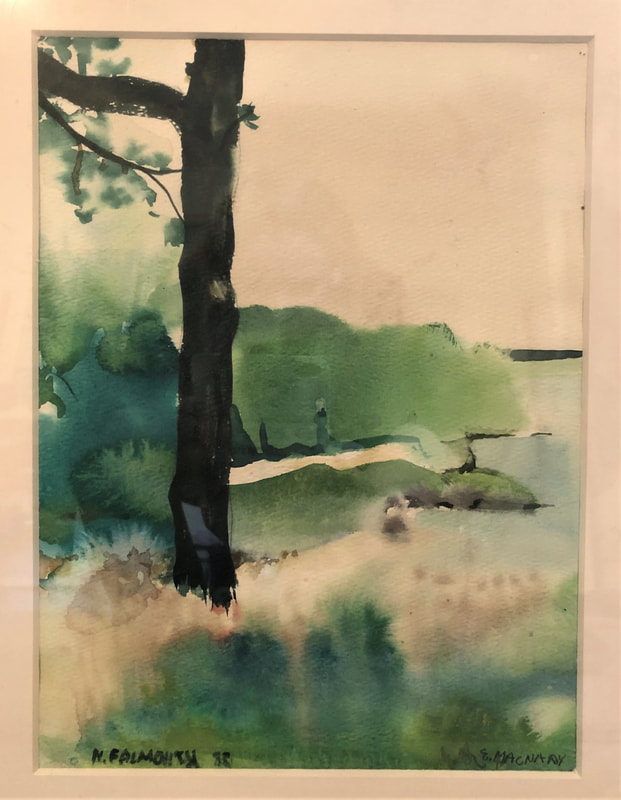

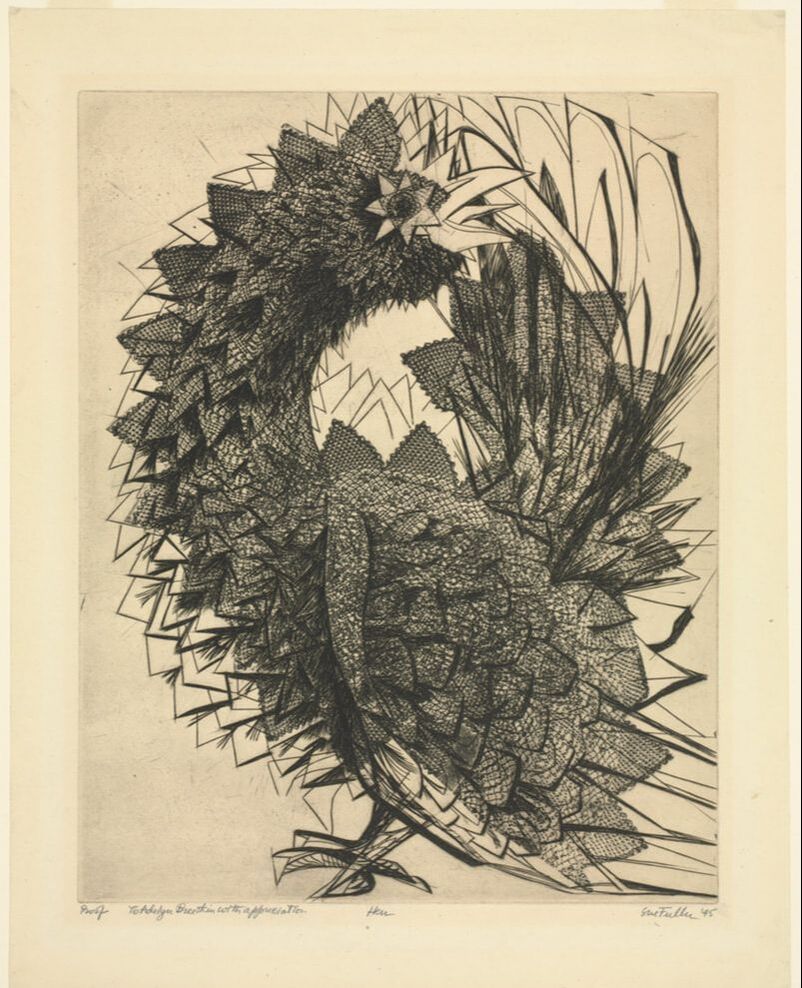

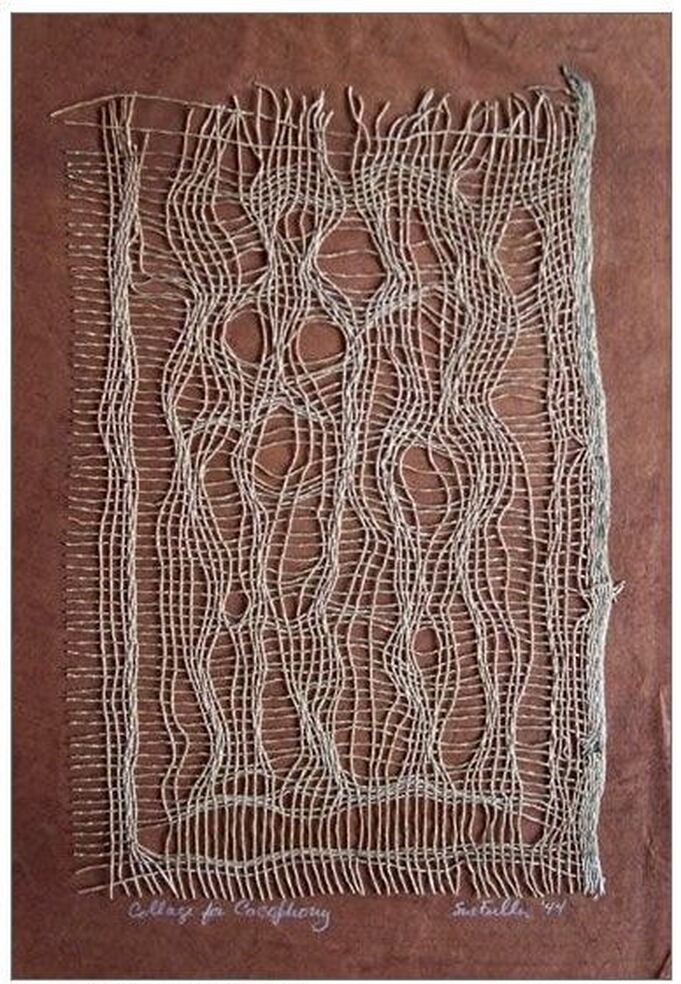

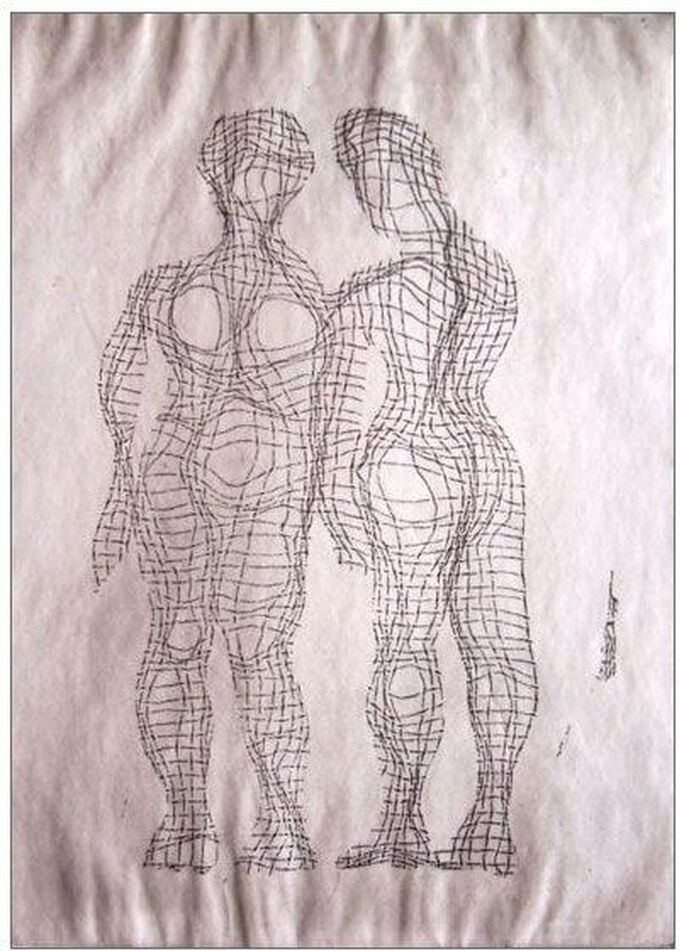

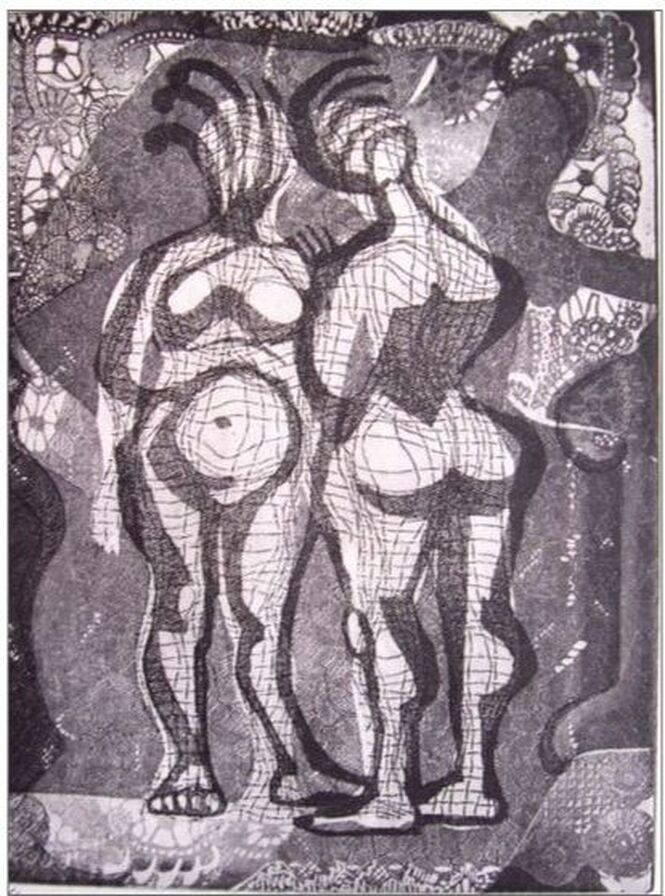

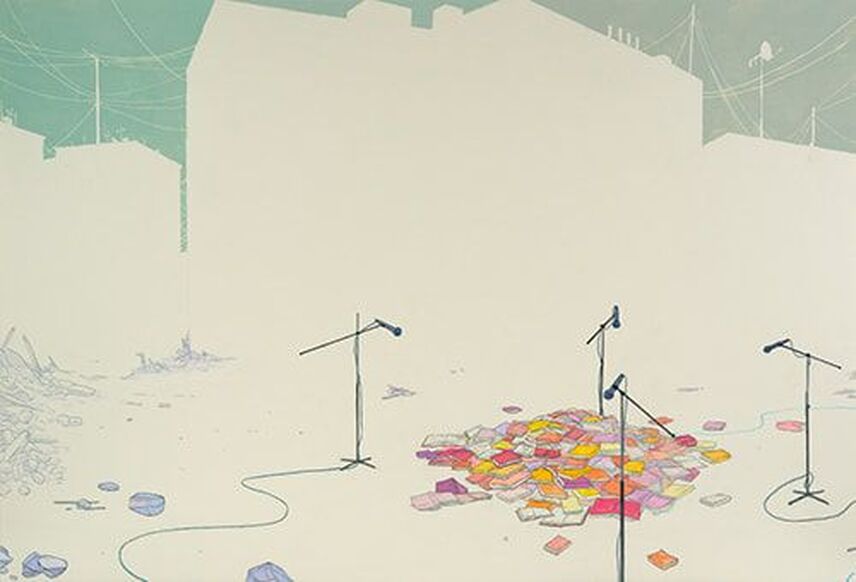

Ann ShaferIt is a truth universally acknowledged that performance art is difficult to collect. Just as with dance or music, when the performance is over, there remains nothing solid. Sure, there might be a recording or video, but the thing itself evaporates as soon as it is done. With performance art, often the tangible, collectible thing is some sort of documentation of it—usually photographs. Rarely does one find a work that is a product of the performance—an indexical work, if you will. When Tru Ludwig and I stumbled across Western Exhibitions’ booth at the Editions and Artists Books Fair (E/AB) in 2011, gallery owner Scott Speh had Stan Shellabarger’s book front and center. Stan Shellabarger is known for extended, endurance performances, say walking in a circle for twelve hours, marking the earth and a moment in time. Taking the idea of creating a drawing on the ground further, Shellabarger also walks in shoes outfitted with graphite or sandpaper on the soles and performs an endurance walk on paper or wood. In this way, the artwork is not only the performance itself, but also the drawing created in the process. Like many before him, Shellabarger wanted to be able to create more than one object from a given performance, and, no surprise, he turned to printmaking. The method Shellabarger came up with to record a performance is known as a reductive or suicide woodcut. In this method, a multi-color print is created using a single block by carving away more of the surface in between printing each color. After drawing the outline of the image on the woodblock, first any areas that are to remain the color of the paper are carved away and the first color is printed. It is critical to print more sheets than you think you will need for the planned edition because you will undoubtedly have several mishaps (that’s where the suicide part comes in). After the first color is printed and the block is cleaned, the artist carves away any area that will remain that first color. After printing the second color, the steps are repeated. In the final cutting, usually all that is left is the key or black line, which brings the whole composition together. Shellabarger used the reduction method but in a slightly different way. The woodblock has the various layers of image cut away by the artist walking on it with sandpaper-soled shoes rather than by carving in the conventional manner. For this walking performance piece, there were multiple boards laid out on the floor and walked upon. After each board was printed, after every walking session and every different color printing, the prints pulled from each board were assembled into accordion-fold books. When fully opened and unfolded, the book reaches eighteen feet. Before beginning to walk, Shellabarger took the boards to Spudnik Press, a cooperative printshop in Chicago, printed the first color, the dark red, ending up with a flat red on each sheet. After walking for a period of time (at least four hours), Shellabarger printed the second color, the dark blue. He repeated the process, wearing away more and more of the blocks by sanding them with his shuffle, and printed each successive layer: green, then medium blue, then finishing with light blue. I included Shellabarger’s book in my exhibition at the BMA called On Paper: Spin, Crinkle, Pluck, which was on view April 19–September 20, 2015. Each of the objects in the exhibition was indexical, meaning the image was the product of its own making. The action verbs in the exhibition title refer to three of the works in the show: spin for Trisha Brown’s softground pirouettes in Untitled Set One, 2006 (BMA 2007.336–338, and the subject of an earlier post); crinkle for Tauba Auerbach’s Plate Distortion II, 2011 (BMA 2012.198); and pluck for Ann Hamilton’s warp & weft I, 2007–08 (BMA 2009.128). We lacked enough room in the gallery to install Shellabarger’s book on the floor, which would enable viewers to really grasp how it was made. Instead, we installed it running up the wall, which brought it into a very nice conversation with the Trisha Brown prints on the adjacent wall. The museum made a video about the work for its 100th Anniversary celebration, BMA Voices. Here is the link to that video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OU4pAdE2z2Q. Stan Shellabarger (American, born 1968) Untitled, 2011 Accordion–bound volume of six–color reduction woodblock print Book: 381 x 559 mm. (15 x 22 in.); sheet (unfolded): 381 x 5588 mm. (15 x 220 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2012 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2012.190  Stan Shellabarger (American, born 1968), Untitled, 2011, accordion–bound volume of six–color reduction woodblock print, book: 381 x 559 mm. (15 x 22 in.); sheet (unfolded): 381 x 5588 mm. (15 x 220 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2012 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2012.190  Installation shot at BMA: Stan Shellabarger (American, born 1968), Untitled, 2011, accordion–bound volume of six–color reduction woodblock print, book: 381 x 559 mm. (15 x 22 in.); sheet (unfolded): 381 x 5588 mm. (15 x 220 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Print, Drawing & Photograph Society Fund, with proceeds derived from the 2012 Contemporary Print Fair, BMA 2012.190  Stan Shellabarger, Untitled Performance (Autumnal Equinox 1994), Madison, WI. On the Autumnal Equinox Shellabarger paced east to west in a straight-line from sunrise to sunset on the lawn of a former astrological observatory. The twelve-hour performance left a narrow path of dead grass on the observatory’s lawn. This mark was visible until the following spring. Photo courtesy of Western Exhibitions.  Stan Shellabarger. Untitled Performance (Sanding 2002) Chicago, IL. Shellabarger paced on a wooden walkway thirty feet by two feet for approximately one hundred and twenty hours. The soles of his shoes were covered with sixty grit sandpaper so as he paced he eroded the surface of the walkway. Eventually he wore a depression over an inch deep into the surface of walkway. Photo courtesy of Western Exhibitions.  Stan Shellabarger. Untitled Performance (Sanding 2002) Chicago, IL. Shellabarger paced on a wooden walkway thirty feet by two feet for approximately one hundred and twenty hours. The soles of his shoes were covered with sixty grit sandpaper so as he paced he eroded the surface of the walkway. Eventually he wore a depression over an inch deep into the surface of walkway. Photo courtesy of Western Exhibitions. Ann ShaferDavid St. Hubbins: It's such a fine line between stupid, and uh... Nigel Tufnel: Clever. David St. Hubbins: Yeah, and clever. (From the movie, This is Spinal Tap) As a curator, I like work that is thoughtful, has a tight conceptual circle, and says a lot using minimal means. I appreciate it if the artist uses techniques that align with the meaning of the work. And I really appreciate it if there is a sly nod to some earlier piece of art history. This latter part is divisive among my colleagues. Is it clever or stupid? Is it derivative or smart in accessing its forebears? I spent many years hosting visitors and classes in the print room and offering critiques in the studios of artists. Occasionally I came across someone who said they didn’t want to learn about artists who came before them because it would influence their thinking and creativity. The sentiment “they have nothing to teach me,” always strikes me as foolhardy. Imagine exhibiting your work and getting comments like, “Oh, so-and-so did work like this in the 1980s.” I always tried to impress upon these non-believers that being ignorant of the work of artists “upon whose shoulders you stand,” to quote Tru Ludwig, is foolish and makes them look stupid rather than clever, in Spinal Tap parlance. Whenever I converse with artists about their work, I think about what other artists they should look at, or specific objects they need to see in the museum’s collection. I always reinforce the idea of visiting print rooms in any museum, which are there for the study of works on paper not on view in the galleries. Normally, 99.9% of the collection of works on paper is only accessible by making an appointment to look at them under supervision in a print room. And most museums, no matter where you are, have such a thing. I believe print rooms are one of the front doors of the museum. As the first contact point for print room visitors, I think it is important to give them access to objects, resources, and me (or whoever is there). Not that I know everything—far from it—but that I could at least offer a suggestion of where to turn next if I didn’t have the answers. Honestly, this was just about the most fun part of the job: watching artists looking at objects you know will spark something in their brains, inevitably leading to better work. Does this mean a work is derivative, a copy, a nod, an appropriation because of ideas formed looking at other objects? Personally, I don’t think so. (There are shades all along the spectrum on this.) I would rather the artist know that someone else thought of it first and that they took the time to think through that aspect and morph it into their own vision of the same idea. I also love that often there is more than one object that speaks to a particular work. Hang on, we’re going down a rabbit hole. Years ago, the museum purchased a drawing by Rachel Perry that is made up of cut slivers of fruit stickers forming loops. That work, S.O.O.O. Good, 2008, is not included in the online database (many, many things aren’t), but it looks a lot like Peach Party, 2012. I always loved the drawing and used it often in classes. That one could take something as mundane as a bunch of fruit stickers and create such a lyrical drawing always struck me as brilliant. While Perry was collecting the fruit stickers for these drawings, she also produced a series of photographs called Lost in my Life that feature the artist obscured and overwhelmed by an overabundance of an everyday object like price tags, twist ties, bread tabs, take-out containers, and, of course, fruit stickers. They are perfect statements about consumerism and waste. When the photograph series was first shown at Yancey Richardson Gallery, I was excited to pitch the photo with the fruit stickers to the museum for acquisition thinking it was a beautiful pendant to the drawing we’d already acquired. My pitch was unsuccessful. But the smallest version of the photograph (Perry published it in three sizes) hangs in my living room. In Lost in my Life (fruit stickers), Perry holds in front of her a patchwork of squares of wax paper upon which she has been storing the fruit stickers she harvested from her family kitchen. The top of her head is visible, as are her bare feet. Through the translucent wax paper, it appears that she is naked, as if she has just emerged from the shower. Behind her, the wallpaper is images of fruit stickers, created by the artist. I was entranced by the photograph anyway, but when my art-partner-travel-companion Tru Ludwig made the connection to Raphaelle Peale’s painting, Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception, c. 1822, I was sold. Peale’s painting is complex and fascinating and warrants further reading. A short description from the Nelson-Atkins Museum (which owns it), is here: https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/30797/venus-rising-from-the-seaa-deception. A rather in-depth look at it both historically and physically is found here: Lauren Lessing and Mary Schafer. “Unveiling Raphaelle Peale’s Venus Rising from the Sea—a Deception.” Winterthur Portfolio 43, no. 2/3 (summer/autumn 2009), pp. 229–59. Suffice it to say that painting a trompe l’oeil kerchief obscuring a nude woman was rather scandalous in 1820s America. The kerchief, a length of fabric worn around a woman’s neck and tucked into her bodice, would have been seen as if not erotic then at least alluring. That it is hiding a nude woman emerging from her bath would have been titillating in puritanical America. Sure, the Europeans had been portraying nudes forever, but not so in this country. It’s an amazing painting and is worth the trip to Kansas City to see. But back to the idea of copying, appropriating, whatever you want to call it. The figure behind the draped kerchief is a direct quotation from a c. 1722 painting by James Barry. I doubt Peale would have seen the Irishman’s painting in person, but no surprise, there was a reproductive print made of the composition to spread Barry’s reputation and imagery. The mezzotint, by Valentine Green, would have likely found its way into a collection in Philadelphia or Baltimore, where Peale would have seen it. The idea of painting drapery in this fashion probably derives from a work by the Spaniard Francisco de Zubarán, whose The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1630s, shows the sudarium with the visage of Jesus Christ, which was imprinted on the veil when Veronica wiped Christ’s face as he carried the cross. Close in composition is Philippe de Champaigne’s etching and engraving after the painting by Nicolas de Plattemontagne—another example of prints as a way of disseminating imagery. They were that time’s Instagram. And of course, one must mention the incredible engraving of the sudarium by Claude Mellan, whose single line starts at the nose and works its way outward. Yes, you read that right, one line. That’s a lot of layers to get back to Rachel Perry’s photograph about contemporary life and consumerism. This through-line deserves a more thorough analysis to be sure, but I thought I would suck you in with this teaser. Rachel Perry (American, born 1962) Peach Party, 2012 Fruit stickers and archival adhesive 279 x 279 mm. (11 x 11 inches) Private Collection Rachel Perry (American, born 1962) Lost in my Life (fruit stickers), 2010 Pigment print 762 x 508 mm. (30 x 20 in.) Private Collection Raphaelle Peale (American, 1774–1825) Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception, c. 1822 Oil on canvas 740 x 613 cm. (29 1/8 x 24 1/8 in.) The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 34-147 James Barry (Irish, 1741–1806) The Birth of Venus, c. 1772 Oil on canvas 260.3 x 170.2 cm. (102 ½ x 67 in.) Dublin City Gallery, the Hugh Lane Valentine Green (British, 1739–1812) after James Barry (Irish, 1741–1806) The Birth of Venus, 1772 Mezzotint Plate: 612 x 391 mm. (24 1/8 x 15 3/8 in.) Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: William A. Whitaker Foundation Art Fund Francisco de Zubarán (Spanish, 1558–1664) The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1630s Oil on canvas 101.6 x 832 cm. (42 ½ x 31 ¼ in.) Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston Nicolas de Plattemontagne (French, 1631–1706) after Philippe de Champaigne (French, 1602–1674) The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1654 Etching and engraving Sheet (trimmed within platemark): 554 x 353 mm. (17 15/16 x 13 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art: Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1998.34.2 Claude Mellan (French 1598–1688) The Sudarium of Saint Veronica, 1649 Engraving Plate: 430 x 318 mm. (16 15/16 x 12 ½ in.) Sheet: 517 x 395 mm. (20 3/8 x 15 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art: Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.6144 Ann ShaferOnce I got through Art History 101 (what a whirlwind), at the beginning of my second year at the College of Wooster I took a class in nineteenth century art (read: French) with the professor that turned me into an art history nut. Arn Lewis was a quiet and intense man whose passion for his subject viscerally came through. I don’t think I ever expected to be excited about any subject that wasn’t studio art or music (oboe, alto). And I remember thinking: finally, something I can sink my teeth into. I was a copious note-taker. Not only did it help me stay awake in the dark classroom, but also it was clear to me that note-taking made the test-taking a whole lot easier. (Actually, I am rather nerdishly proud that I have never fallen asleep in an art history lecture.) We were exploring the oeuvre of French artist Edouard Manet one day and I was busily jotting something down when I looked up to see Bouquet of Lilacs (c. 1882) on the screen. This was my first jaw-dropping art history moment, which I have referred to several times in earlier posts. Edouard Manet, who some think of as the father of Modernism, painted some magnificent paintings. (Please note I claim zero expertise in Manet.) In the fall of 1983, there was a blockbuster exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was my “home” museum having grown up in the NY suburbs. All the biggies were there. The Balcony (1868–69) was the mascot, if you will. It was on the cover of the catalogue and was made into a poster that I had in my dorm room throughout college and graduate school. I honestly can't recall, and don't have the catalogue handy, to know if other key works were also in the exhibition. But some of his most important paintings include: Olympia (1863), Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), The Railway (1872–73), and A Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882). It was my first blockbuster show, and at the time I had no idea museums and curating exhibitions were going to be my career (I’ll save the story of when that lightbulb went off for another post). Manet died at fifty-one, a year after painting A Bar at the Folies Bergère. He had contracted syphilis in his forties and was in considerable pain in his final years. He suffered from jerky, uncontrolled body movements and had his left foot amputated eleven days before he died. In that last year, Manet painted Bouquet of Lilacs and other flowers and fruit as symbols of transience, a kind of vanitas. Apparently one of his close friends, Méry Laurent, brought him flowers every day, and Manet painted them against a plain background. One assumes it was to better focus on the fragile beauty of the blooms. What made my jaw drop in that classroom in Ohio? Part of it, I’m sure, was the scale. It was really big up on that screen--it's 21 x 16 inches in reality. Part of it was because the flowers are set against a dark background in the painting, and in that dark classroom those white blossoms really popped. But I think what really got me was the way he captured the stems in the water and the glass. How did he paint the water? We’re sure the water level is halfway up, but the way he paints the stems in and out of the water are exactly the same but not. What the heck! As a would-be artist, all I could think was: no fair, you bastard! Edouard Manet (1832–1883) Bouquet of Lilacs, c. 1882 Oil on canvas 54 x 42 cm. (21 ¼ x 16 ½ in.) Nationalgalerie | Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin © Photo: Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz Edouard Manet (1832-1883) The Balcony, 1868–69 Oil on canvas 170 x 124.5 cm. (67 x 49 in.) Musée d'Orsay: Gustave Caillebotte Bequest, 1894 © Musée d'Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt Ann ShaferMothers’ Day is not a big deal in our house. The husband does not believe we should let Hallmark dictate when to say, “I love you,” since we tell each other that every day. I don’t disagree, but sometimes these holidays sneak up on you and leave an impression. This year, I’m guessing due to this crazy quarantine/deadly virus issue, I’m missing my mom more than usual. Ellen Medart MacNary was a graduate of Wash U’s art school and continued to paint throughout her life. I don’t know if she had any formal training in watercolors (I doubt it), but she seemed to pick it up effortlessly. I would watch her and sometimes try to copy what she was doing, without a tremendous amount of luck. Good thing I dropped my studio art aspirations for art history, which gave my father much relief since he felt he had watched Mom “suffer” as an artist to gain recognition. He veritably begged me not to major in studio art at the College of Wooster. During our summer vacations, either sailing in Maine and Nova Scotia, or camping in any number of places with our trusty VW bus (the regular one, not the camper one) and two tents, Mom brought watercolors with her. She carried a small tackle box full of brushes and tubes, along with a small palette, and a block of watercolor paper. When we anchored for the night, or set up camp somewhere, she would pull out her paints and jot off something like it was nothing. In one of the watercolors you can see a little girl sitting at a picnic table. Mom and I were driving to Nova Scotia to collect the rest of the family as they disembarked from a trip sailing my grandfather’s Concordia Yawl, Westray, from Maine to Nova Scotia (another family would take her from there). I think that drive, and the several nights we camped along the way, was the only time I ever traveled with Mom by myself. Boy, was that a treat. There are a good number of Mom’s watercolors out there in the world and are prized possessions. At my house, most of them are resting in the dark at the moment (watercolor is highly susceptible to light damage), so when I pulled them out to photograph them, it was lovely to see the group together. I especially love the one of me sitting at that picnic table. Ann ShaferVarious print dealers made annual visits to the BMA’s print department, during which we were able to look through several boxes and portfolio carriers they brought. More often than not, we retained one or more works for possible acquisition. One day in 2011, a particular dealer came who always had great stuff to offer. Out of one of the medium-sized boxes came an etching by Horst Janssen. It caught my eye immediately for several reasons. One, it’s totally cool. Two, the subject is Edgar Allan Poe, who Baltimore claims as one of its own because he died here. Three, Poe’s poem The Raven is the reason Baltimore’s NFL team is called the Ravens. Four, Horst Janssen was unrepresented in the collection. Five, museum director Doreen Bolger was working on an exhibition about Poe and it seemed a great addition. Six, we had been searching for an appropriate work to bring into the collection in memory of Doreen’s mother, who had recently passed away (back then it was customary for museum members to send in some money to be put toward an acquisition for a particular person’s retirement or death). In other words, it was a no brainer. Horst Janssen was an amazingly prolific printmaker in nearly every technique (everything but screenprinting). He completed landscapes, portraits of notable people including Edgar Allan Poe, erotica, as well as a huge number of self-portraits. A glance at a sequence of the self-portraits shows every bit of his hard life, which was challenging: he never knew his father, his mother died when he was fourteen, he had multiple marriages and children, he was an alcoholic, and probably had a host of other issues. As for Poe, Janssen portrays him as a bit of a kook, or at least as a tortured soul like the artist himself. Poe’s nose seems to have broken down, his eyes are unfocused, the bags under his eyes rival his eyebrows, his hair is a fright, a bug crawls up the right-hand side of the composition, and his tie seems to be made of a crustacean of some sort. This is a portrait of a tortured artist/creative, raising all sorts of questions about artistic genius and whether one must be a bit crazy to access that kind of creativity. But that’s a debate for another day. Horst Janssen (German, 1929–1995) Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, 1988 Color etching Sheet: 686 x 483 mm. (27 x 19 in.) Plate: 559 x 381 mm. (22 x 15 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased in Memory of Alice Bolger with funds contributed by her Friends, Staff and Board of Trustees of The Baltimore Museum of Art, BMA 2011.70 © Horst Janssen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn  Horst Janssen (German, 1929–1995), Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, 1988, color etching, sheet: 686 x 483 mm. (27 x 19 in.); plate: 559 x 381 mm. (22 x 15 in.), Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased in Memory of Alice Bolger with funds contributed by her Friends, Staff and Board of Trustees of The Baltimore Museum of Art, BMA 2011.70 © Horst Janssen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Ann ShaferA spirit of collaboration and experimentation was at the heart of Atelier 17. Prints by Hayter and his associates are conceptually and passionately full of ideas about the human condition, dreams, mythology, war, and natural phenomena. The exceptional rigor of subject matter in these images was achieved by means of three technical innovations, which changed the course of twentieth century printmaking. First, Hayter revived the art of engraving, which he believed was uniquely suited to address issues of modern art. (Historically engraving had been used to reproduce more famous works for a large market.) Second, members of the studio pioneered the use of textiles, paper, string, wood, and other materials pressed into a softground-coated plate to gain an amazing variety of textures. Third, Hayter and his colleagues (credit to Krishna Reddy and Kaiko Moti) developed several inventive methods of printing in colors from a single plate, eliminating the need to print separate plates for each color. All of these are counterintuitive to admirers of traditions intaglio prints. While looking at the works from this studio, know that often when you think you are seeing etching, it is actually engraving. When you think you are seeing aquatint, it is really softground etching. When you see a color print, it is not the result of each color being printed from separate plates, but of being applied to a single plate. Today’s post zooms in on the second element, softground etching. Not a new technique by any means, the possibilities were greatly expanded by one of the women artists working at Atelier 17, Sue Fuller, who used bits of fabric that went beyond a simple pattern like pantyhose used to create tonal passages mimicking aquatint. Rather, she utilized lace and pieces of string to create the subject of the image itself. Fuller’s print Hen, 1945, is the clearest example of this in its use of a lace collar to form the hen. Fuller’s Cacophony, 1944, features several standing female figures, which are delineated by string. Fortunately for us, Fuller also created collages of some of her compositions, including the one for Cacophony, which is currently “on view” in an online exhibition from Susan Teller Gallery. Seeing the collage of string in the same composition really brings it together and enables viewers to imagine what is meant by softground etching. Teller also is showing the first state and the final, all of which makes clear the composition’s creation. Susan Teller is the go-to person for works by Fuller. Her breadth of knowledge and depth of stock by Fuller and others who worked at the Atelier during its New York years is legendary. The online exhibition is here. For a superb read on Sue Fuller and the many female artists working at Atelier 17, look no further than the recently published book by Christina Weyl, The Women of Atelier 17: Modernist Printmaking in Midcentury New York (Yale University Press, 2019). Christina’s accomplishment with her book is tremendous and it is required reading for students of this era. Yesterday, Joanne B Mulcahy published a review of Christina’s book for Hyperallergic, beautifully summing up its contents. I suspect there may be a run on the book from online sources; I suggest if you are thinking a procuring a copy, act fast. Sue Fuller (American, 1914–2006) Hen, 1945 Engraving and softground etching Sheet: 458 x 364 mm. (18 1/16 x 14 5/16 in.) Plate: 378 x 299 mm. (14 7/8 x 11 3/4 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Adelyn D. Breeskin, BMA 1948.52 Sue Fuller (American, 1914–2006) Cacophony, 1944 Collage 11 x 8 inches Susan Teller Gallery, New York (courtesy the Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York) Sue Fuller (American, 1914–2006) Cacophony (first state), 1944 Softground etching, 11 x 8 inches Susan Teller Gallery, New York (courtesy the Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York) Sue Fuller (American, 1914–2006) Cacophony (final state), 1944 Etching, softground etching, and aquatint 11 x 8 inches Susan Teller Gallery, New York (courtesy the Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York) Ann ShaferSometimes my pitch for a potential acquisition failed for one reason or another, and I kept a list of them, the ones that got away. And sometimes the ones that got away felt like they needed to find their way into my own collection. (Once the museum declares it is not interested in a work, one is free to pursue it oneself.) Such was the case with Amze Emmons, a terrific artist based in Philadelphia. I first became aware of Amze because of the blog he worked on with friends and colleagues Robert Tillman and Jason Urban called Printeresting. The blog’s tagline was “The thinking person's favorite resource for interesting print miscellany.” Luckily for everyone, the site is archived here: https://archive.printeresting.org/. Back in 2012, Ben Levy and I invited the three to give a talk at the museum during the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. They also created a post about the fair, which is here: http://archive.printeresting.org/2012/05/06/baltimore-contemporary-print-fair/?fbclid=IwAR2nXkMqKRc4VmrV3fUA62rSsI0G-fHU3ZcO86rxOVMy_TMoMKvVvBlGg0s. Amze teaches printmaking at the Tyler School of Art, part of Temple University. In addition, he is an artist, curator, and critic. He’s an eloquent thinking person with abundant energy. In his work he often looks for objects and ideas that are particular to place yet universal. Many have a dystopian feel. One drawing caught my eye because it not only speaks to Amze’s overall themes, but also it speaks to social protest and history. Publisher Publisher is a drawing in graphite and gouache (opaque watercolor) from 2014. In an empty urban lot is a pile of discarded books surrounded by microphones on stands. The books have the opportunity to speak through the microphones, but are, by nature, incapable. The missing link is us. We are the only ones that can ingest and distill the books’ information and turn around and share that knowledge aurally (or is it orally). What information the books hold is unknowable, unless we rescue them for this pile, open them, and give them our attention. The possibility is right there on the precipice and is only lacking human care and intervention. I see a push-pull of knowledge and ignorance, of potential and impotence, of knowledge and its censure, of sorrow at the books' destruction, of them as symbols of humans’ frailty, and fear of other, of learning, of living. My pitch for its acquisition fell on deaf ears. But all is not lost. The drawing now graces the walls of my dining room. It’s a rare work that appeals to my industrial-Americana-loving husband, my own need for beauty, and my deep desire for works that pack a punch. Amze, I thank you and I tip my hat to you. Amze Emmons (American, born 1974) Publisher Publisher, 2014 Gouache and graphite 26 x 38 in. Private Collection |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed