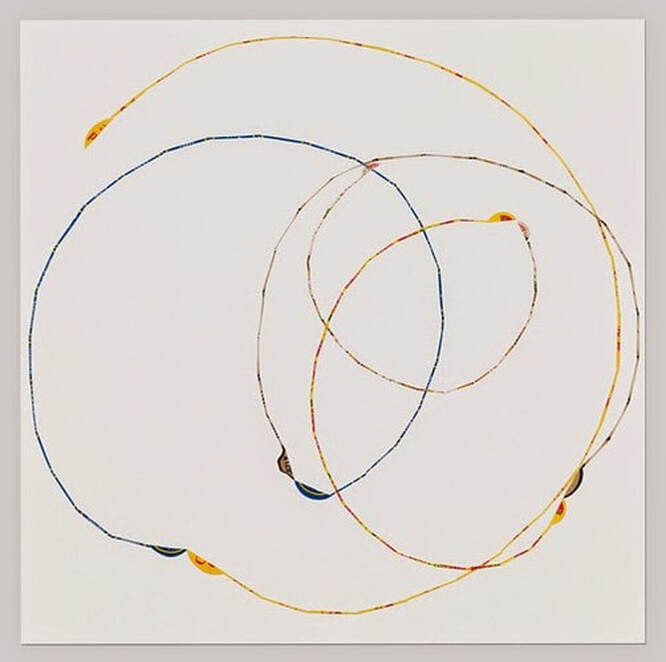

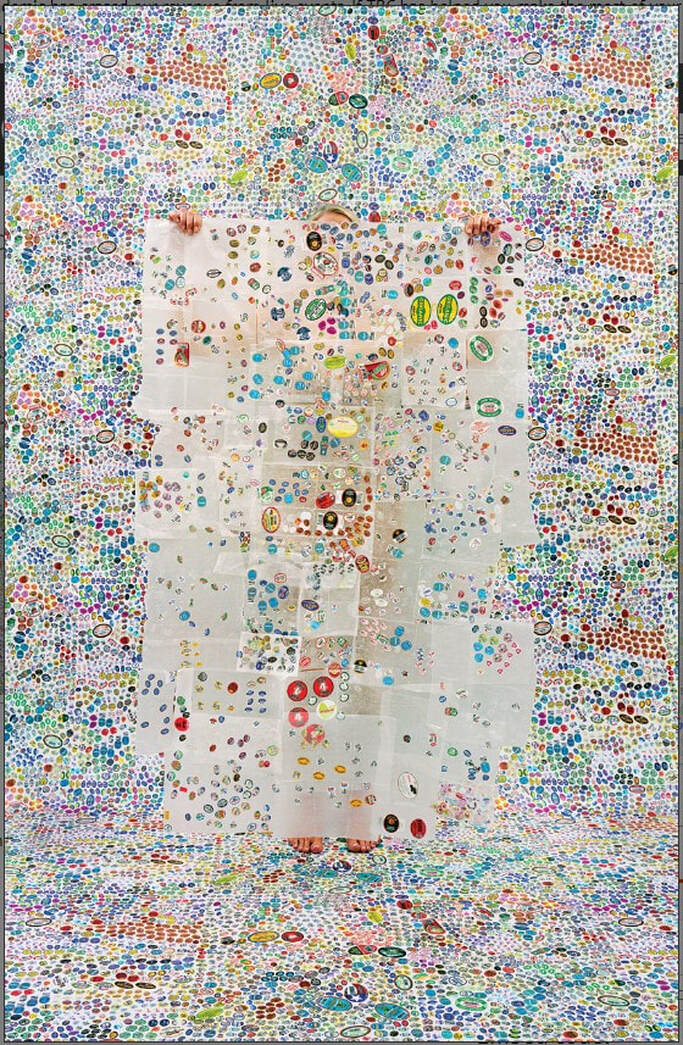

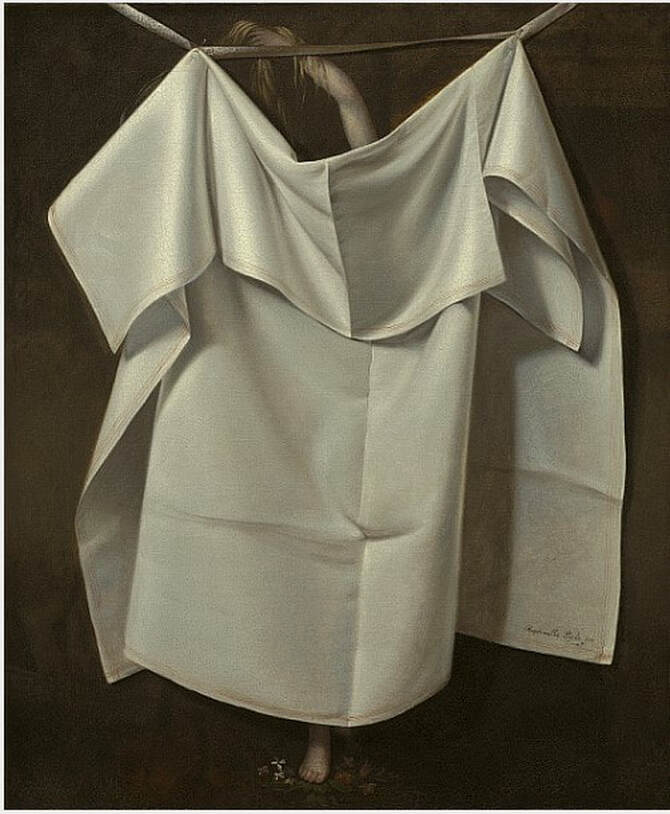

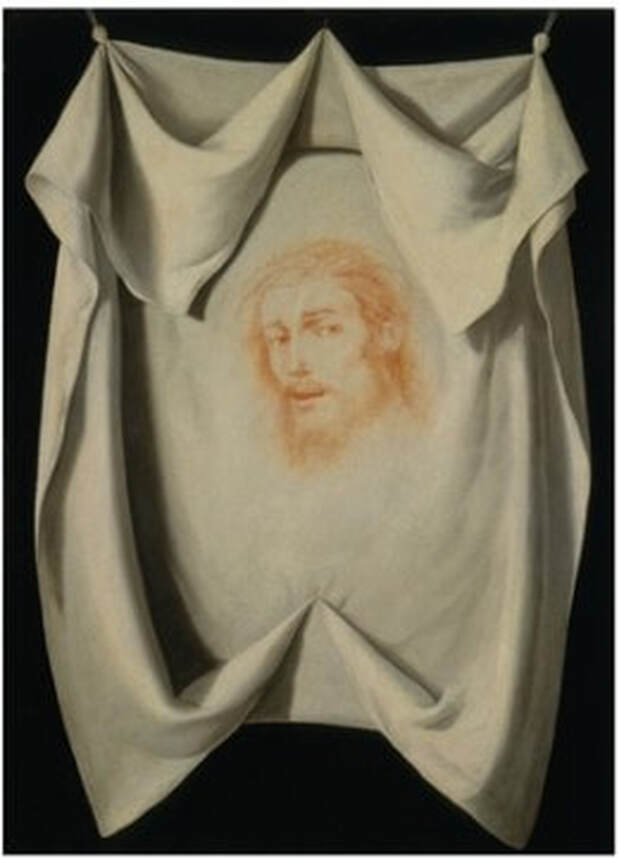

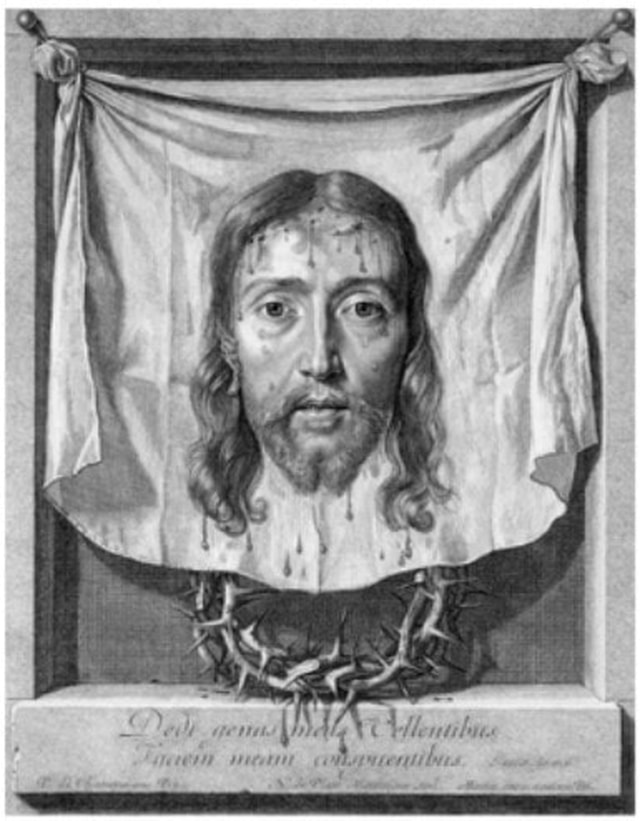

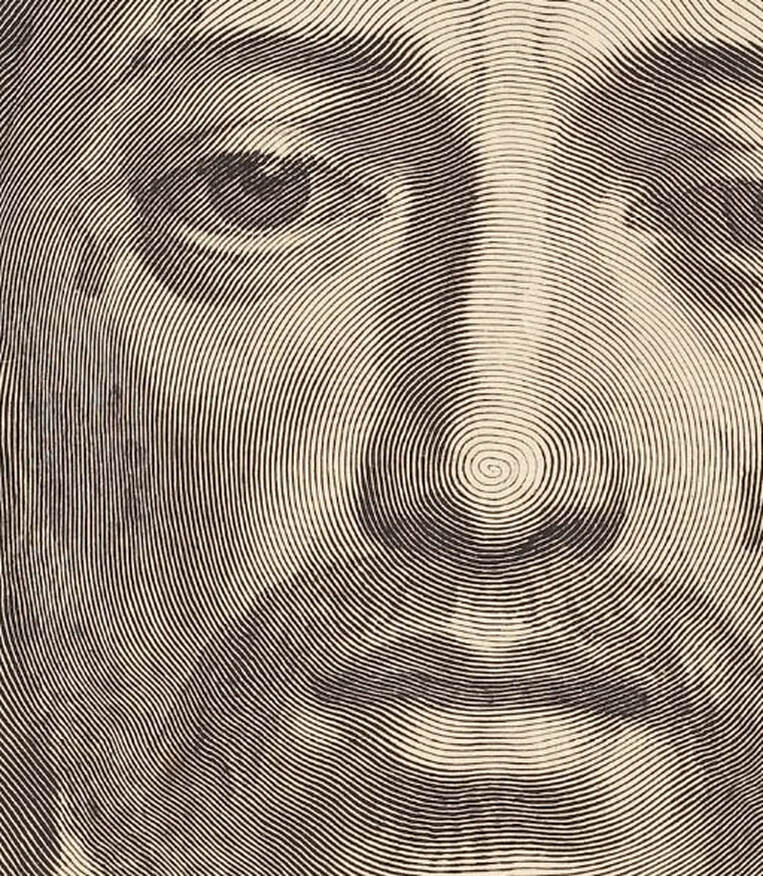

Ann ShaferDavid St. Hubbins: It's such a fine line between stupid, and uh... Nigel Tufnel: Clever. David St. Hubbins: Yeah, and clever. (From the movie, This is Spinal Tap) As a curator, I like work that is thoughtful, has a tight conceptual circle, and says a lot using minimal means. I appreciate it if the artist uses techniques that align with the meaning of the work. And I really appreciate it if there is a sly nod to some earlier piece of art history. This latter part is divisive among my colleagues. Is it clever or stupid? Is it derivative or smart in accessing its forebears? I spent many years hosting visitors and classes in the print room and offering critiques in the studios of artists. Occasionally I came across someone who said they didn’t want to learn about artists who came before them because it would influence their thinking and creativity. The sentiment “they have nothing to teach me,” always strikes me as foolhardy. Imagine exhibiting your work and getting comments like, “Oh, so-and-so did work like this in the 1980s.” I always tried to impress upon these non-believers that being ignorant of the work of artists “upon whose shoulders you stand,” to quote Tru Ludwig, is foolish and makes them look stupid rather than clever, in Spinal Tap parlance. Whenever I converse with artists about their work, I think about what other artists they should look at, or specific objects they need to see in the museum’s collection. I always reinforce the idea of visiting print rooms in any museum, which are there for the study of works on paper not on view in the galleries. Normally, 99.9% of the collection of works on paper is only accessible by making an appointment to look at them under supervision in a print room. And most museums, no matter where you are, have such a thing. I believe print rooms are one of the front doors of the museum. As the first contact point for print room visitors, I think it is important to give them access to objects, resources, and me (or whoever is there). Not that I know everything—far from it—but that I could at least offer a suggestion of where to turn next if I didn’t have the answers. Honestly, this was just about the most fun part of the job: watching artists looking at objects you know will spark something in their brains, inevitably leading to better work. Does this mean a work is derivative, a copy, a nod, an appropriation because of ideas formed looking at other objects? Personally, I don’t think so. (There are shades all along the spectrum on this.) I would rather the artist know that someone else thought of it first and that they took the time to think through that aspect and morph it into their own vision of the same idea. I also love that often there is more than one object that speaks to a particular work. Hang on, we’re going down a rabbit hole. Years ago, the museum purchased a drawing by Rachel Perry that is made up of cut slivers of fruit stickers forming loops. That work, S.O.O.O. Good, 2008, is not included in the online database (many, many things aren’t), but it looks a lot like Peach Party, 2012. I always loved the drawing and used it often in classes. That one could take something as mundane as a bunch of fruit stickers and create such a lyrical drawing always struck me as brilliant. While Perry was collecting the fruit stickers for these drawings, she also produced a series of photographs called Lost in my Life that feature the artist obscured and overwhelmed by an overabundance of an everyday object like price tags, twist ties, bread tabs, take-out containers, and, of course, fruit stickers. They are perfect statements about consumerism and waste. When the photograph series was first shown at Yancey Richardson Gallery, I was excited to pitch the photo with the fruit stickers to the museum for acquisition thinking it was a beautiful pendant to the drawing we’d already acquired. My pitch was unsuccessful. But the smallest version of the photograph (Perry published it in three sizes) hangs in my living room. In Lost in my Life (fruit stickers), Perry holds in front of her a patchwork of squares of wax paper upon which she has been storing the fruit stickers she harvested from her family kitchen. The top of her head is visible, as are her bare feet. Through the translucent wax paper, it appears that she is naked, as if she has just emerged from the shower. Behind her, the wallpaper is images of fruit stickers, created by the artist. I was entranced by the photograph anyway, but when my art-partner-travel-companion Tru Ludwig made the connection to Raphaelle Peale’s painting, Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception, c. 1822, I was sold. Peale’s painting is complex and fascinating and warrants further reading. A short description from the Nelson-Atkins Museum (which owns it), is here: https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/30797/venus-rising-from-the-seaa-deception. A rather in-depth look at it both historically and physically is found here: Lauren Lessing and Mary Schafer. “Unveiling Raphaelle Peale’s Venus Rising from the Sea—a Deception.” Winterthur Portfolio 43, no. 2/3 (summer/autumn 2009), pp. 229–59. Suffice it to say that painting a trompe l’oeil kerchief obscuring a nude woman was rather scandalous in 1820s America. The kerchief, a length of fabric worn around a woman’s neck and tucked into her bodice, would have been seen as if not erotic then at least alluring. That it is hiding a nude woman emerging from her bath would have been titillating in puritanical America. Sure, the Europeans had been portraying nudes forever, but not so in this country. It’s an amazing painting and is worth the trip to Kansas City to see. But back to the idea of copying, appropriating, whatever you want to call it. The figure behind the draped kerchief is a direct quotation from a c. 1722 painting by James Barry. I doubt Peale would have seen the Irishman’s painting in person, but no surprise, there was a reproductive print made of the composition to spread Barry’s reputation and imagery. The mezzotint, by Valentine Green, would have likely found its way into a collection in Philadelphia or Baltimore, where Peale would have seen it. The idea of painting drapery in this fashion probably derives from a work by the Spaniard Francisco de Zubarán, whose The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1630s, shows the sudarium with the visage of Jesus Christ, which was imprinted on the veil when Veronica wiped Christ’s face as he carried the cross. Close in composition is Philippe de Champaigne’s etching and engraving after the painting by Nicolas de Plattemontagne—another example of prints as a way of disseminating imagery. They were that time’s Instagram. And of course, one must mention the incredible engraving of the sudarium by Claude Mellan, whose single line starts at the nose and works its way outward. Yes, you read that right, one line. That’s a lot of layers to get back to Rachel Perry’s photograph about contemporary life and consumerism. This through-line deserves a more thorough analysis to be sure, but I thought I would suck you in with this teaser. Rachel Perry (American, born 1962) Peach Party, 2012 Fruit stickers and archival adhesive 279 x 279 mm. (11 x 11 inches) Private Collection Rachel Perry (American, born 1962) Lost in my Life (fruit stickers), 2010 Pigment print 762 x 508 mm. (30 x 20 in.) Private Collection Raphaelle Peale (American, 1774–1825) Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception, c. 1822 Oil on canvas 740 x 613 cm. (29 1/8 x 24 1/8 in.) The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 34-147 James Barry (Irish, 1741–1806) The Birth of Venus, c. 1772 Oil on canvas 260.3 x 170.2 cm. (102 ½ x 67 in.) Dublin City Gallery, the Hugh Lane Valentine Green (British, 1739–1812) after James Barry (Irish, 1741–1806) The Birth of Venus, 1772 Mezzotint Plate: 612 x 391 mm. (24 1/8 x 15 3/8 in.) Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: William A. Whitaker Foundation Art Fund Francisco de Zubarán (Spanish, 1558–1664) The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1630s Oil on canvas 101.6 x 832 cm. (42 ½ x 31 ¼ in.) Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston Nicolas de Plattemontagne (French, 1631–1706) after Philippe de Champaigne (French, 1602–1674) The Veil of Saint Veronica, 1654 Etching and engraving Sheet (trimmed within platemark): 554 x 353 mm. (17 15/16 x 13 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art: Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1998.34.2 Claude Mellan (French 1598–1688) The Sudarium of Saint Veronica, 1649 Engraving Plate: 430 x 318 mm. (16 15/16 x 12 ½ in.) Sheet: 517 x 395 mm. (20 3/8 x 15 9/16 in.) National Gallery of Art: Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.6144

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed