Ann Shafer What happens if you live in Melbourne in the early part of the twentieth century in an era of pretty conservative art making? How do you learn about what is going on in Europe and other places that are so far away? There is no television, no internet.

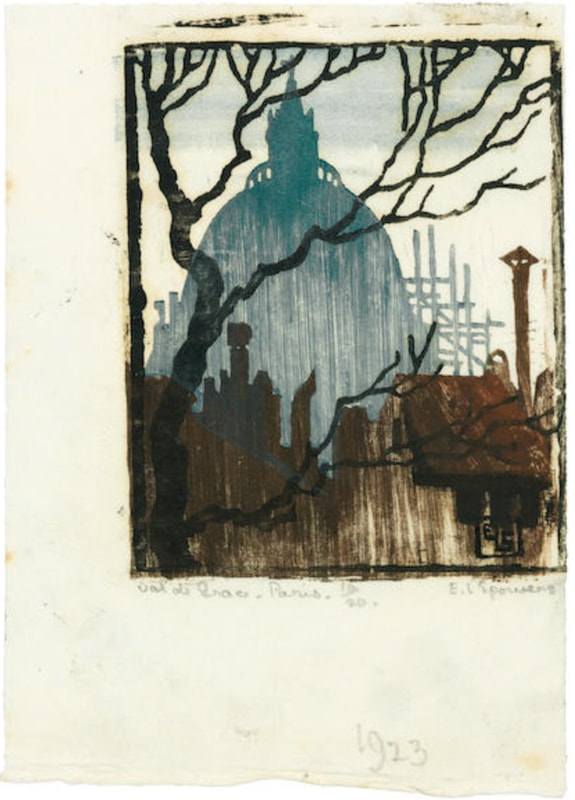

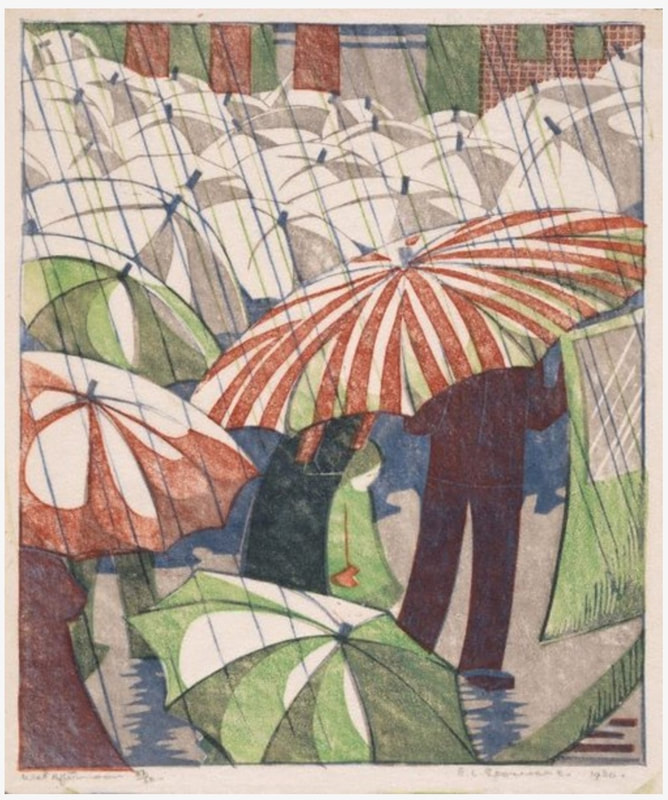

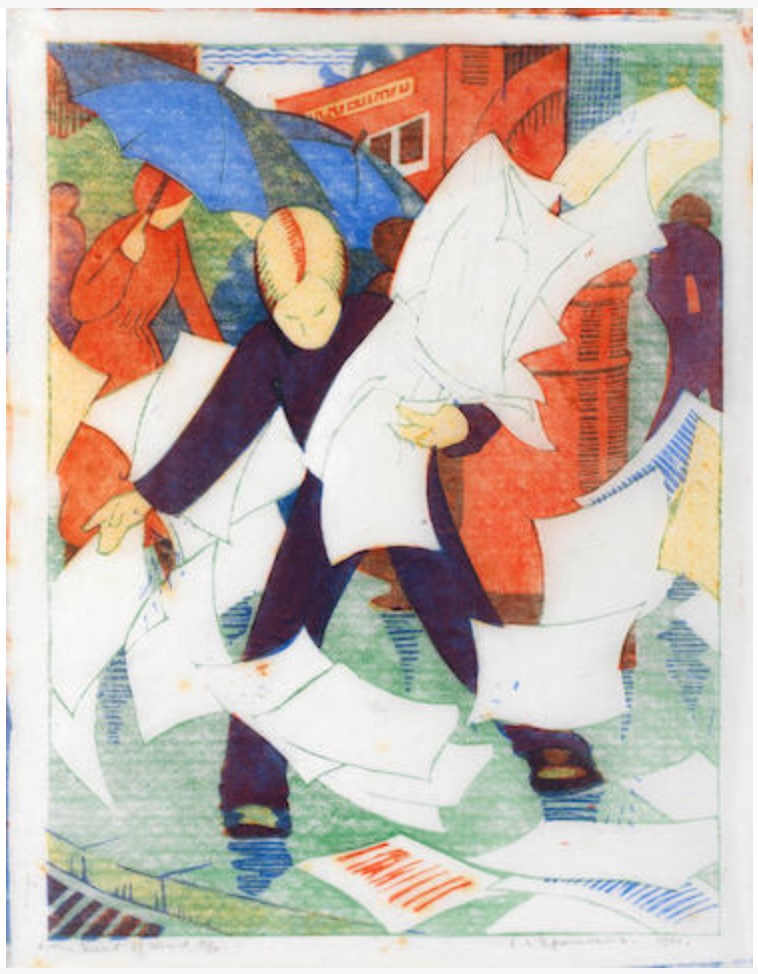

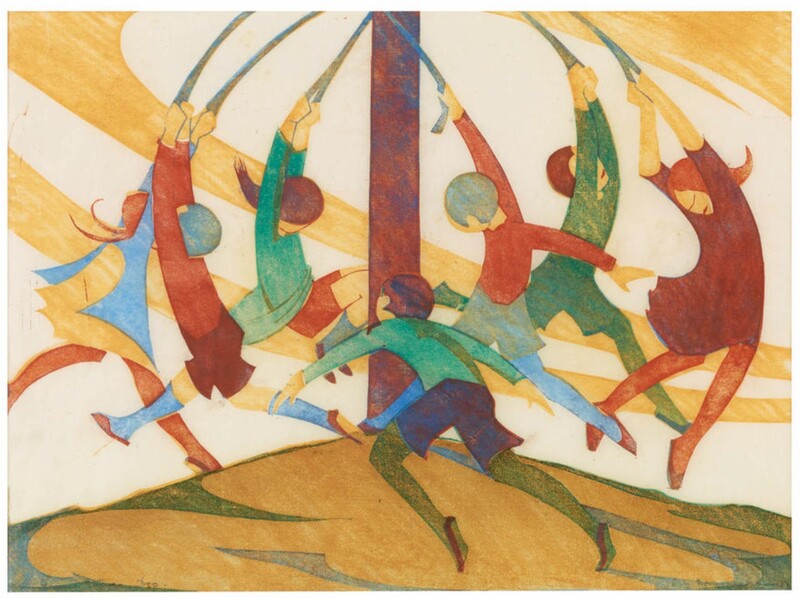

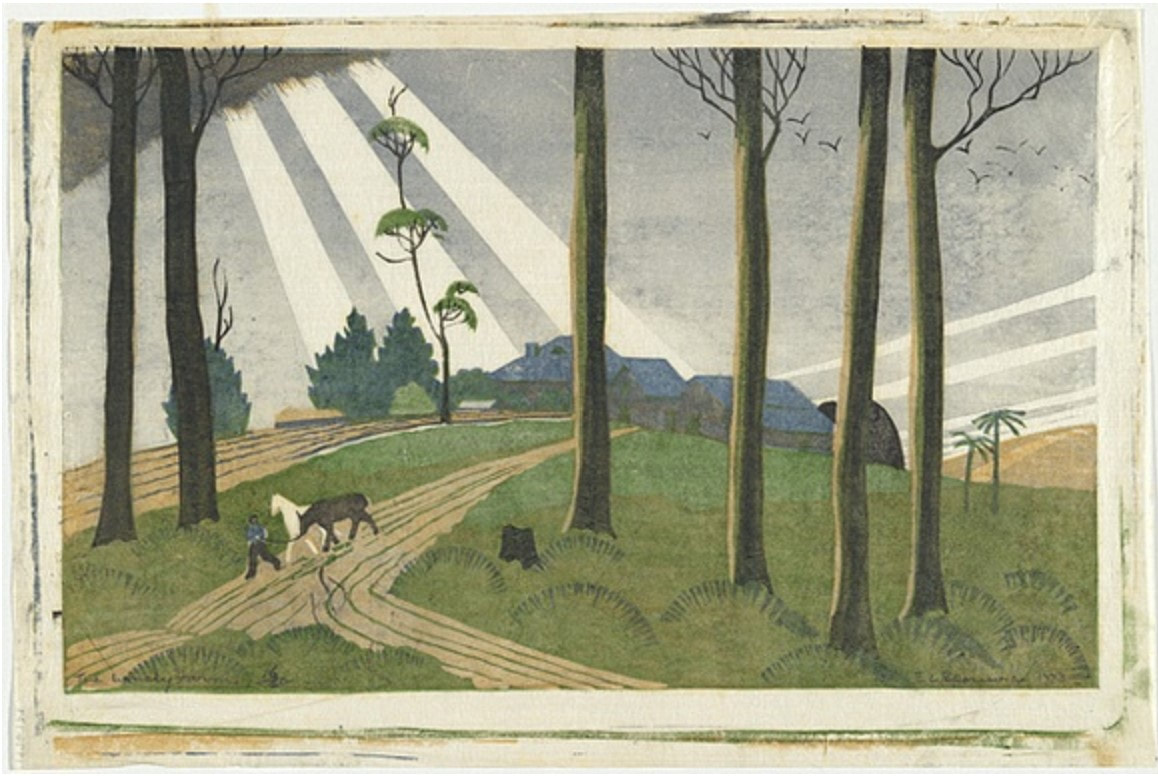

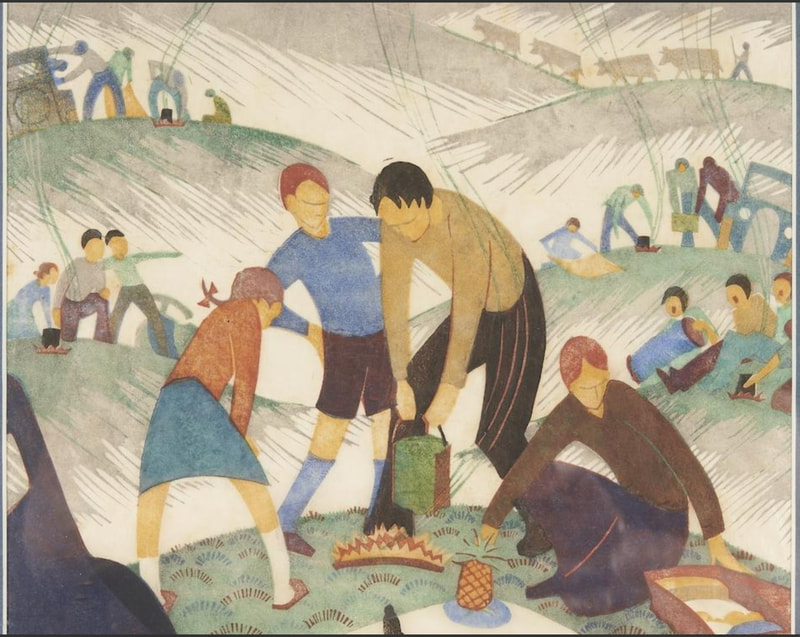

Why, one goes to libraries and book stores to find publications that might expand one’s horizons. One such oasis of cosmopolitan culture in Melbourne was found at the Depot Bookshop run by the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria. It was there in 1928 that a young artist named Eveline Syme came across a small booklet called Lino-Cuts, written by Claude Flight. Claude Flight was the well-known teacher at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in London who was the defacto leader of a group of printmakers named for the school. (We recently met Lill Tschudi and Ursula Fookes who both studied there.) Syme and another young artist, Ethel Spowers, would have seen the school advertised in The Studio, the leading British art-periodical also available at the Depot Bookshop. Both women were so taken by the illustrations in Flight's booklet that they traveled to London and enrolled—Spowers arrived in late 1928, and Syme came a few months later, in 1929. Located in London's Warwick Square, the Grosvenor School was an informal place that offered up random courses. It had a growing reputation due mainly to Flight who was one of its charismatic teachers. He inspired many artists to work in linoleum cuts in multiple colors (one block for each color) and to adopt Flight’s method of using both printing ink and oil paint to achieve particular color effects. Flight promoted the idea of the democratic virtue of linoleum cuts as a cheap commodity in an overpriced art market. (The Grosvenor School closed its doors in 1940.) Syme wrote about Flight and his style: “Sometimes in his classes it is hard to remember that he is teaching, so complete is the camaraderie between him and his students. He treats them as fellow-artists rather than pupils, discusses with them and suggests to them, never dictates or enforces. At the same time he is so full of enthusiasm for his subject, and his ideas are so clear and reasoned that it is impossible for his students not to be influenced by them." Today’s artist, Spowers, studied with Flight from 1928 to 1930, went home for a bit, and returned to London in 1931 for a spell. During her time back home in 1930, she mounted a show, Exhibition of Linocuts, at the Everyman Lending Library in Melbourne that featured her prints as well as those by Syme and fellow Aussie Dorrit Black. In turn, the three women all found an outlet at the Modern Art Center established in Sydney by Black in 1931. Spowers also acted as an informal agent for Flight, promoting his work down under. Spowers, sadly, died of cancer at the young age of 56 in 1947. Meanwhile, in England, influential touring exhibitions, arranged in conjunction with the Redfern Gallery, traveled around promoting the linoleum cuts of the Grosvenor School, and included the work of the Australian women. Linoleum cut prints by the artists of the Grosvenor School were popular until they seemed too colorful and optimistic in the face of the War. They fell off the radar and it wasn’t until the 1970s that there was really any market for them. Now, of course, their prices are sky high.

0 Comments

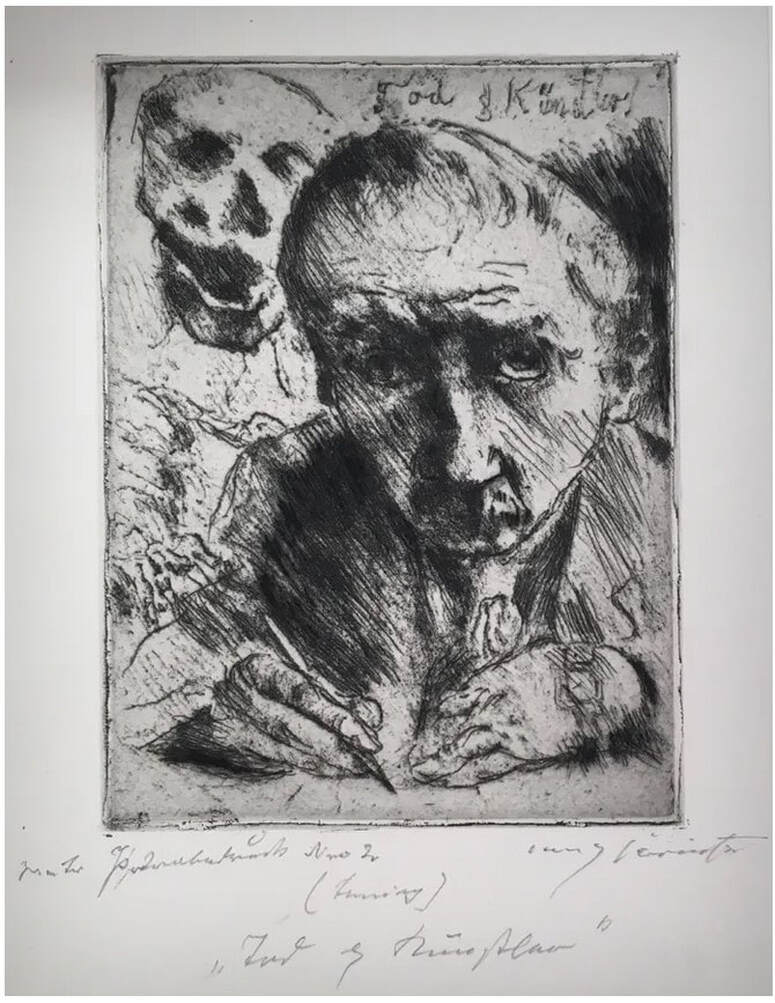

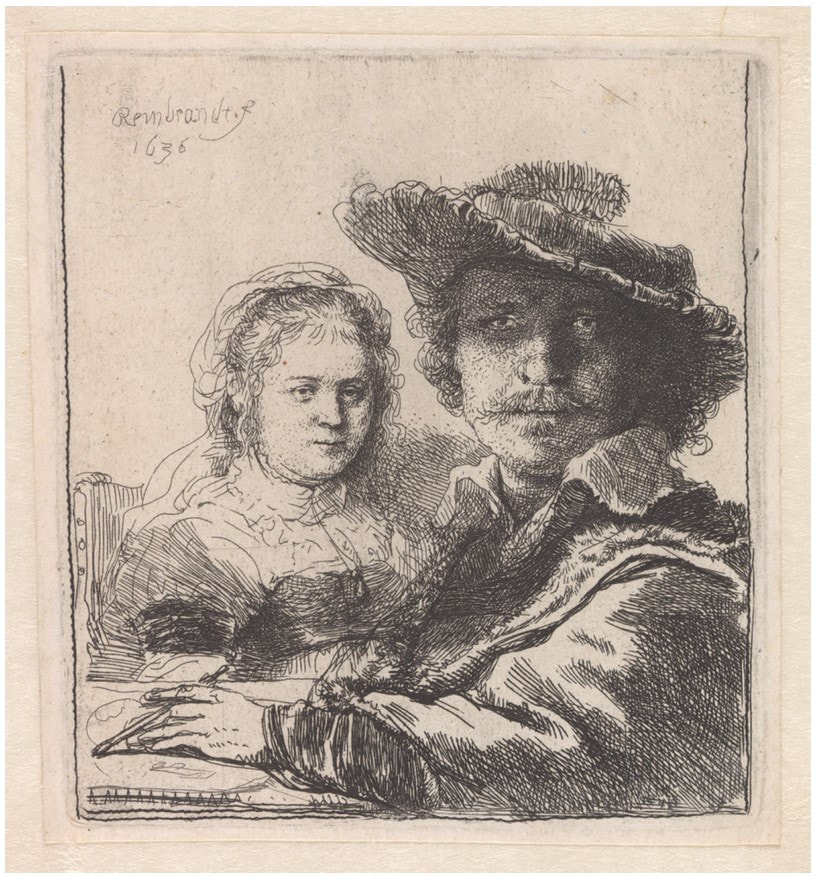

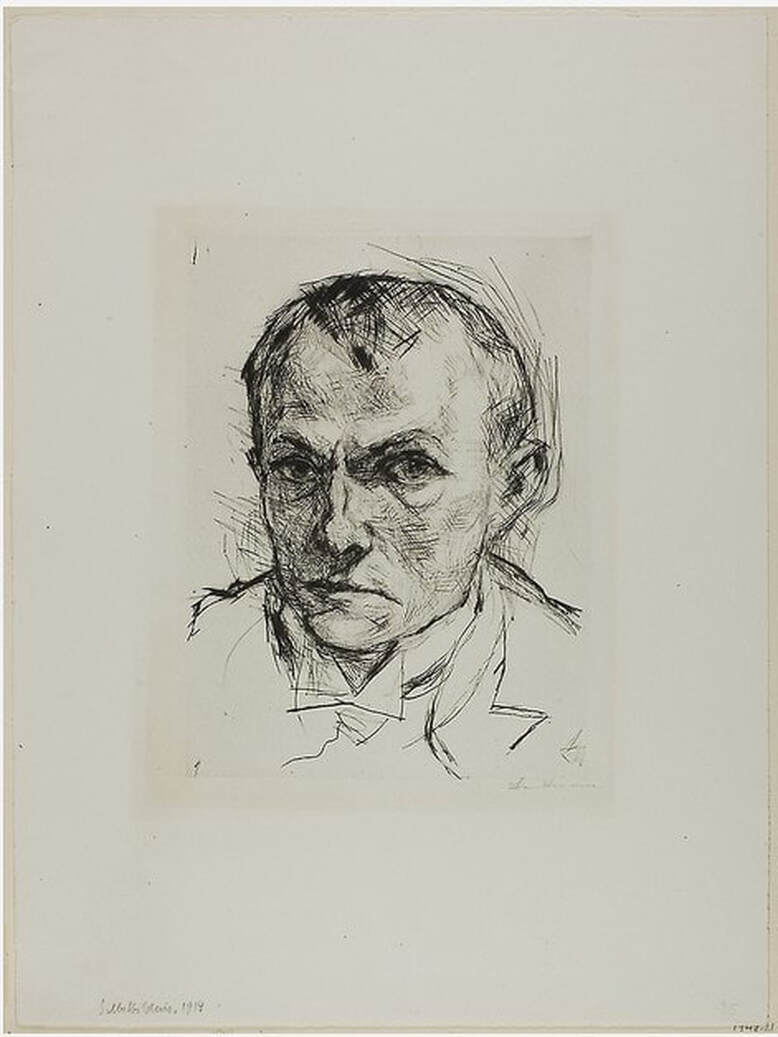

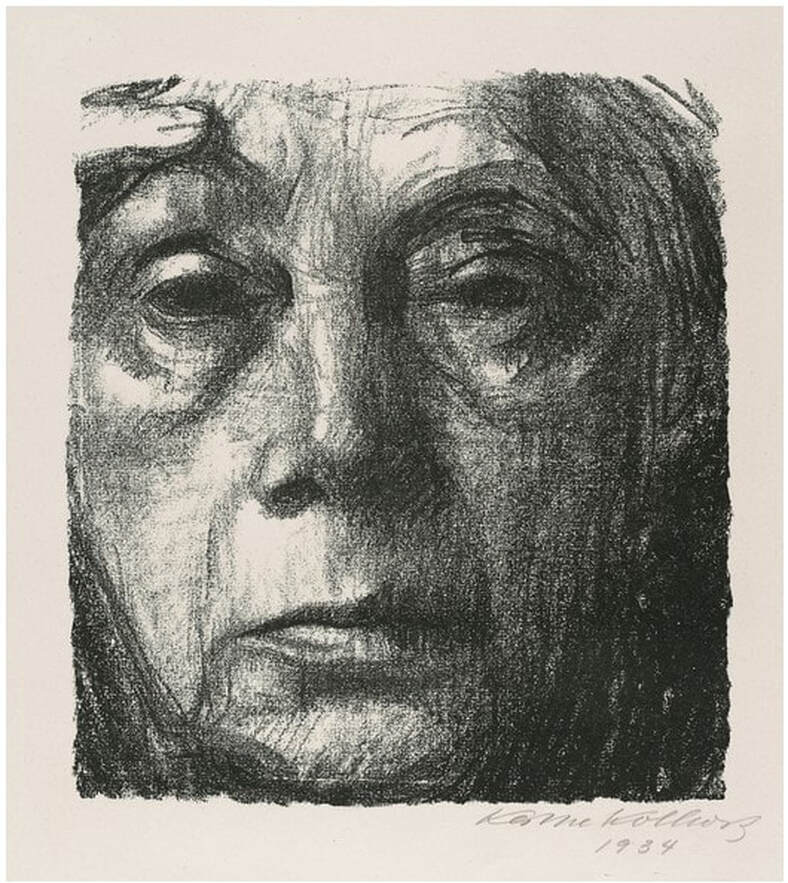

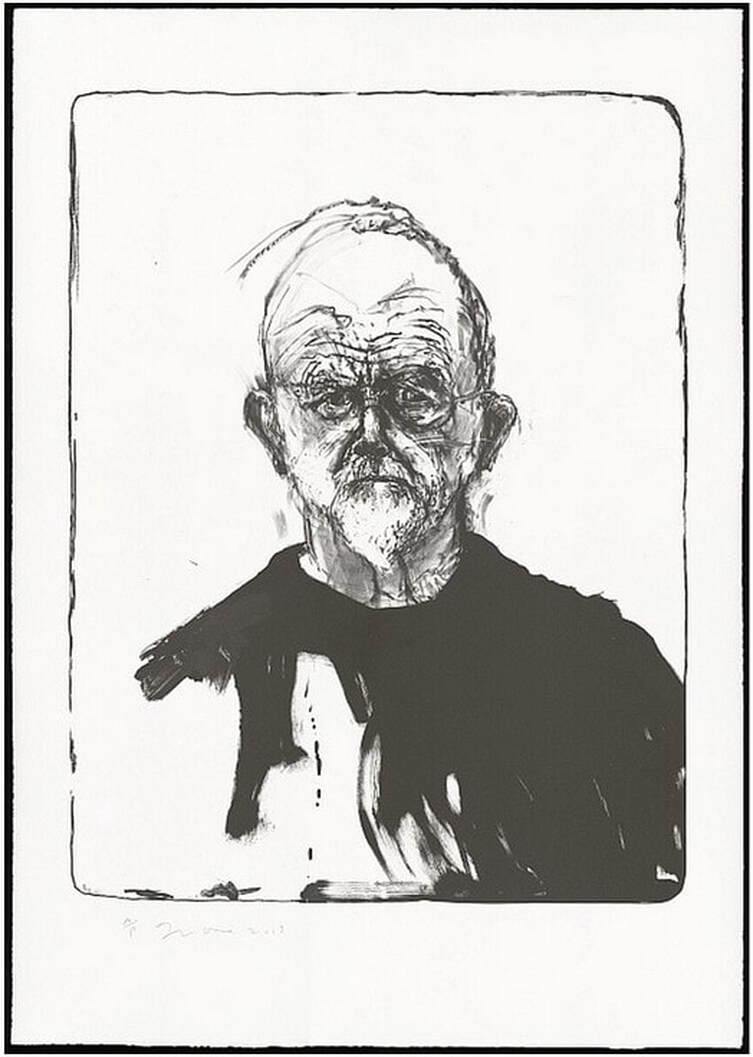

Ann Shafer When I started working for Full Circle, I was curious to see what kinds of art was in its stable, and what I could do to bring any of it to light for you. One painting, which is hanging in Catalyst Contemporary’s “backroom” among other represented artists’ works, I just love. It’s by Damon Arhos and it’s a self-portrait. I’ve always been fascinated by self-portraits and why they are rife throughout art. Let’s look back for a minute before we get to Arhos’ painting. In Western art the first self-portrait is believed to be by Jan van Eyck in 1466. Why then; why him? Likely it has to do with the development of clear, useful mirrors. Until then, there was no way to see ourselves with any accuracy. Those first mirrors must have surprised and delighted. Consider, too, that historically there had been little distinction between individual artists and artisan-craftsmen of guilds, so no cause for taking one’s own likeness. Individualism was not a thing yet. When and who decided that an artist’s work was the product of immense and unusual talent worthy of a signature and individual notice? I’m sure there are other examples, but my printmaking mind goes directly to our old friend Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) since he was a master of self-promotion and marketing. He drew his first self-portrait at age 13—but it is a drawing and its circulation was limited. Hell, he wasn’t even a professional artist at that age. But I’ve always been impressed that by 1500 (age 28) he had the kahunas to portray himself in the guise of Jesus Christ. I mean, honestly. Self-portraits were a way of promoting one’s talent, a calling card if you will. Plus, the model was accessible and cheap. But more than that, they are a means of introspection. Self-portraiture enables artists to look inside, figure out who and what they are, how they want to be seen. Many artists have made them, but how many have really dug in and investigated their own selves in a serial manner? Obviously for me, printmakers come to mind: Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Jim Dine. It’s fascinating to think about what drives us to picture ourselves and to what end. I’d suggest artists use self-portraiture to reflect on what it means to be human, creative, alive. These days, are self-portraits still relevant, especially in this era of selfies, or do they seem old fashioned? What if the self-portrait was only one element in a work that explores more than the physical features of a face? The painting hanging in the backroom at Catalyst Contemporary, which I mentioned at the top of this post, is by Damon Arhos who unfolds queer culture and seeks to promote love and acceptance while investigating social and political issues of gender and sexuality across media. He uses pop culture references fused with the personal to make his work approachable to viewers, and also to be true to himself. In Agnes Moorehead & Me (No. 1/Figure Portrait), 2019, Arhos digitally combined his own face with that of actor Agnes Moorehead as the basis for the painting. The two are merged in a stylistic way with an acidy palette—I love that mustard color. It's one of a series of Moorehead paintings. But why Moorehead? She was an accomplished actor who is now best known as Endora, the mother of the main character in the 1960s television series Bewitched. Endora and her brother Uncle Arthur, played with zeal by gay actor Paul Lynde, became lightning rods for the gay community in subsequent decades due to the characters themselves, but also because of assumptions made about the actors’ personal lives. For Arhos, who would have watched Bewitched in reruns, Uncle Arthur was the first positive, if coded, gay character to come across the television screen. And Endora was full-on glamour and fabulousness. What better character to use to explore one’s identity and challenge gender normativity? In Arhos’ hands, the merged image of two faces is reductive and colorful, playful and serious, objective and subjective. He’s used the idea of a self-portrait but turned it into something that is not recognizable as such. Rather, it becomes a symbol for absorbing different identities into oneself in order to expand the possibility of a more open concept of self, one without boundaries or constraints, norms or rules. It speaks of openness, love, inclusion, everyone’s uniqueness, as well as wishes and hopes for a day when one can be whoever one wants to be. In other words, it’s a masterwork. Damon Arhos (American, born 1967) Agnes Moorehead & Me (No. 1/Figure Portrait), 2019 Acrylic on hardboard panel 40 × 30 × 2 in (101.6 × 76.2 × 5.1 cm) Catalyst Contemporary, Baltimore Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, c. 1390–1441) Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), 1433 Oil on oak 26 x 19 cm (10 ¼ x 7 ½ in) National Gallery, London Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528) Self-Portrait, 1484 Silverpoint 27.5 x 19.6 cm (10 5/8 x 7 5/8 in) Albertina, Vienna Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528) Self-Portrait, 1500 Oil on panel 67.1 cm × 48.9 cm (26.4 in × 19.3 in) Alte Pinakothek, Munich Rembrandt van Rijn (Netherlandish, 1606–1669) Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636 Etching Plate: 10.5 x 9.4 cm (4 1/8 x 3 11/16 in) Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950) Self-Portrait, 1914 Drypoint Plate: 239 × 179 mm (9 3/8 x 7 1/16 in) Art Institute of Chicago: H. Simons Fund, 1948.21 Lovis Corinth (German, 1858–1925) Death and the Artist (Tod und Künstler), from the series Dance of Death (Totentanz) 1921, published 1922 Etching, soft-ground etching, and drypoint Plate: 23.9 x 17.9 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/16 in) Block Museum, Northwestern University, Evanston: Gift of James and Pamela Elesh, 1999.21.13 Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945) Self-Portrait, 1934 Crayon lithograph Image: 20.5 x 18.5 cm (8 1/16 x 7 3/8 in) National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Jim Dine (American, born 1935) Berlin 1, 2013 Lithograph 140.4 x 99.2 cm (55 ¼ x 39 in) Albertina, Vienna: Gift of the Artist and Diana Michener, DG2015/68  Lovis Corinth (German, 1858–1925). Death and the Artist (Tod und Künstler), from the series Dance of Death (Totentanz) 1921, published 1922. Etching, soft-ground etching, and drypoint. Plate: 23.9 x 17.9 cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/16 in). Block Museum, Northwestern University, Evanston: Gift of James and Pamela Elesh, 1999.21.13. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed