Ann Shafer For all that museums are going through at the moment—financial hardships due to covid-19 closures, reckoning with their ingrained colonialism, rewriting the art historical canon to include women and BIPOC, reckoning with a spate of questionable deaccessioning, dealing with issues of social justice and diversity both externally in programming and internally with staff composition—I still believe in the transformative power of art.

If you have been following along, you know that there have been three times in my life when my jaw dropped in response to a work of art. The first was in a college art history class looking at a slide of an Edouard Manet still life of lilacs in a vase. The second time was in the tiny garden behind Charles Demuth’s Lancaster home over which an enormous church steeple looms. I've written posts about both of these moments; hope you check them out. The third time my jaw dropped was while standing in front of Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas, 1656, at the Prado in Madrid. Of the three moments, this was the most surprising occurrence for me. My love for Demuth is such that I spent my senior year in college writing my thesis on him. And who doesn’t love a beautiful still life by Manet? My reaction to Las Meninas surprised me because I have no training in art of the seventeenth century, have never taken a class in Spanish art of any sort, and only know what I’ve read in the skimmiest way possible. The combination of my lack of knowledge and my reaction to it means, for me, Velasquez’s painting is the ultimate example of transformative art. I have avoided writing about the painting because of my lack of knowledge. There’s a lot to pull apart while attempting to get at its meaning and why it is visually so spectacular. But recently a link to an article about it crossed my feed. So, here’s that article, which I encourage you to check out. Also, if you ever find yourself in Madrid, don’t miss Las Meninas at the Prado. Diego Velasquez (Spanish, 1599-1660) Las Meninas, 1656 Oil on canvas 318 x 276 cm (125.2 x 108.7 in) Museo del Prado, Madrid

0 Comments

Ann ShaferOnce I got through Art History 101 (what a whirlwind), at the beginning of my second year at the College of Wooster I took a class in nineteenth century art (read: French) with the professor that turned me into an art history nut. Arn Lewis was a quiet and intense man whose passion for his subject viscerally came through. I don’t think I ever expected to be excited about any subject that wasn’t studio art or music (oboe, alto). And I remember thinking: finally, something I can sink my teeth into. I was a copious note-taker. Not only did it help me stay awake in the dark classroom, but also it was clear to me that note-taking made the test-taking a whole lot easier. (Actually, I am rather nerdishly proud that I have never fallen asleep in an art history lecture.) We were exploring the oeuvre of French artist Edouard Manet one day and I was busily jotting something down when I looked up to see Bouquet of Lilacs (c. 1882) on the screen. This was my first jaw-dropping art history moment, which I have referred to several times in earlier posts. Edouard Manet, who some think of as the father of Modernism, painted some magnificent paintings. (Please note I claim zero expertise in Manet.) In the fall of 1983, there was a blockbuster exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was my “home” museum having grown up in the NY suburbs. All the biggies were there. The Balcony (1868–69) was the mascot, if you will. It was on the cover of the catalogue and was made into a poster that I had in my dorm room throughout college and graduate school. I honestly can't recall, and don't have the catalogue handy, to know if other key works were also in the exhibition. But some of his most important paintings include: Olympia (1863), Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), The Railway (1872–73), and A Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882). It was my first blockbuster show, and at the time I had no idea museums and curating exhibitions were going to be my career (I’ll save the story of when that lightbulb went off for another post). Manet died at fifty-one, a year after painting A Bar at the Folies Bergère. He had contracted syphilis in his forties and was in considerable pain in his final years. He suffered from jerky, uncontrolled body movements and had his left foot amputated eleven days before he died. In that last year, Manet painted Bouquet of Lilacs and other flowers and fruit as symbols of transience, a kind of vanitas. Apparently one of his close friends, Méry Laurent, brought him flowers every day, and Manet painted them against a plain background. One assumes it was to better focus on the fragile beauty of the blooms. What made my jaw drop in that classroom in Ohio? Part of it, I’m sure, was the scale. It was really big up on that screen--it's 21 x 16 inches in reality. Part of it was because the flowers are set against a dark background in the painting, and in that dark classroom those white blossoms really popped. But I think what really got me was the way he captured the stems in the water and the glass. How did he paint the water? We’re sure the water level is halfway up, but the way he paints the stems in and out of the water are exactly the same but not. What the heck! As a would-be artist, all I could think was: no fair, you bastard! Edouard Manet (1832–1883) Bouquet of Lilacs, c. 1882 Oil on canvas 54 x 42 cm. (21 ¼ x 16 ½ in.) Nationalgalerie | Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin © Photo: Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz Edouard Manet (1832-1883) The Balcony, 1868–69 Oil on canvas 170 x 124.5 cm. (67 x 49 in.) Musée d'Orsay: Gustave Caillebotte Bequest, 1894 © Musée d'Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt Ann ShaferEdward Hopper, the original social distancer. Seems like the perfect time to write about the first artist I studied in depth. Back in college, I was aiming at American paintings, mainly of the first half of the twentieth century. That I ended up a print person surprises me still since I backed into their study unintentionally. I wrote my junior thesis on Edward Hopper and his depiction of women in paintings. (Tip of the hat to my brother Ren MacNary, who helped me type it--on a typewriter.) I think I tried to approach it with a feminist lens but really, I was writing from my gut. I haven’t looked back at it in years; I don’t even know if I still have a copy, which is just as well. New York Movie, 1939, is one of my favorite Hopper paintings featuring a lone figure. I’m fascinated by artists’ depictions of the audience and the loneliness that can be felt in a room full of people. Hopper’s woman is a great example of the theme of alone in a crowd.

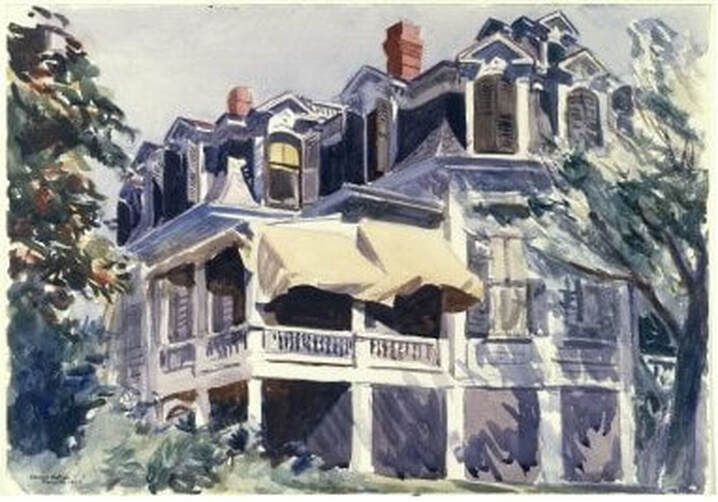

Like so many artists, Hopper also made work in other media as a regular part of his practice. I have a soft spot in my heart for good watercolors (I dabble, and my mother was pretty darn good at them) and Hopper painted some real beauties like The Mansard Roof, 1923. I love that he portrays Victorian domestic architecture (considered out of fashion at the time) rather than the picturesque harbor of the fishing village of Gloucester, Massachusetts, which was the focus of other artists working there in the twenties. Painted on an angle and from below, the house’s billowing yellow awnings dominate. While this is an accurate representation of the house, really it is an exercise in light and shadow. When he painted this house in 1923, Hopper was spending the first of six summers in Gloucester, was trying out watercolor for the first time, and had just met his soon-to-be-wife, Josephine Nivinson. In addition, after not selling any work for the prior ten years, this watercolor was included in an exhibition at, and subsequently purchased for the collection of, the Brooklyn Museum. Not bad for a first stab at the notoriously difficult medium of watercolor. His facility with the brush reminds me of another watercolorist who seemed to be able to whip off a gorgeous work in no time, John Singer Sargent. Because of my own experience and love of watercolors, landing a first job as a curator in a works on paper department represented a shift, but a good one. It wasn’t until much later that I made the final shift to loving prints, which are a tough sell to the public. The barriers to entry are many: the technical information is challenging and complicated, the concept of multiples is confusing, and what does “original” mean anyway. But, once we get people past a certain point, they’re in. Hence my self-identification as a print evangelist. My transition to the dark side was completed under the expert eye of Tru Ludwig. We’ve looked at thousands of prints together and he is my rock. Prior to painting in watercolor in Gloucester, Hopper began making etchings in 1915. He is said to have taught himself, but there is some thought that he learned some of the technical ins and outs from Martin Lewis (more on him in a future post). Of his seventy-some etchings (only 28 were published), my favorite is American Landscape, 1920. Formally, it is such an odd composition with its horizontality and the main subjects—a group of cows trundling over railroad tracks—occupying the lower half of the composition. Only the top of the house rises into the sky. Perhaps we could read into it that Hopper’s prevailing theme of loneliness is personified in the house that is cut off from society by the railroad tracks. Perhaps the cows are the farmer’s only link to the outside world. Who knows? But I do know that to our twenty-first century eyes, the composition looks like a film still: dramatic angle, stark lighting, mundane action portending the future. It all seems apropos in these times of pandemics, quarantines, and social distancing. Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) New York Movie, 1939 Oil on canvas 81.9 x 101.9 cm (32 1/4 x 40 1/8 in.) Museum of Modern Art, 396.1941 Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967) The Mansard Roof, 1923. Watercolor over graphite 352 x 508 mm. (13 7/8 x 20 in.) Brooklyn Museum: Museum Collection Fund, 23.100 Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967) American Landscape, 1920 Etching Sheet: 326 x 442 mm. (12 13/16 x 17 3/8 in.) Plate: 185 x 313 mm. (7 5/16 x 12 5/16 in.) National Gallery of Art: Rosenwald Collection, 1949.5.70 |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed