Ann Shafer During History of Prints class, it’s impossible to show everything. After each class, Tru Ludwig and I would reassess our lists and see where we could make cuts in the early periods to make room for the contemporary works at the end that the museum had recently acquired. For a while we had early Italian female printmaker Diana Scultori as the first woman to appear on the chronological list, but she got bumped off at some point (sorry Diana). If I recall correctly, the BMA’s prints by her were not great representations of her work. So, the first woman on the list became Geertruydt Roghman (Dutch, 1625–1657), an artist from an extensive artist family in Amsterdam.

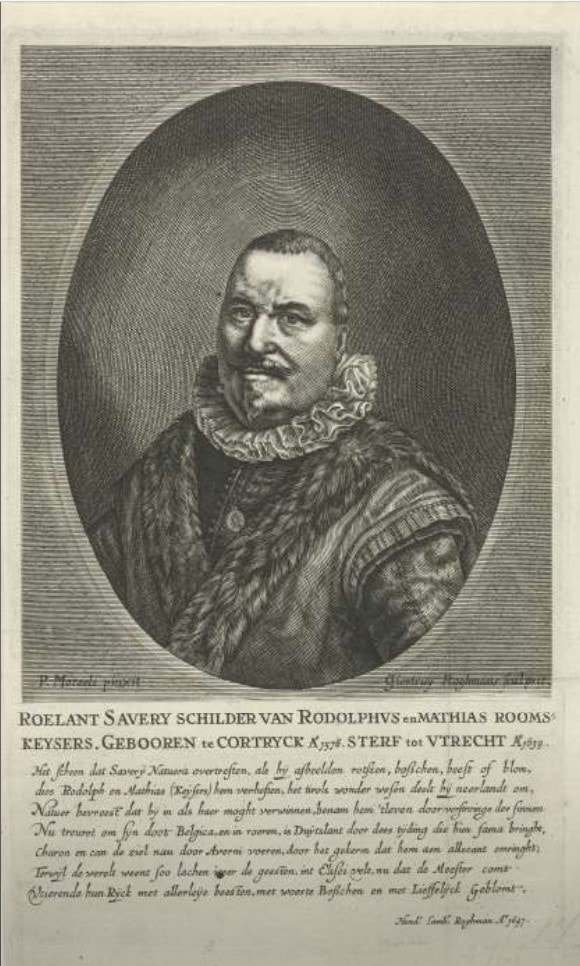

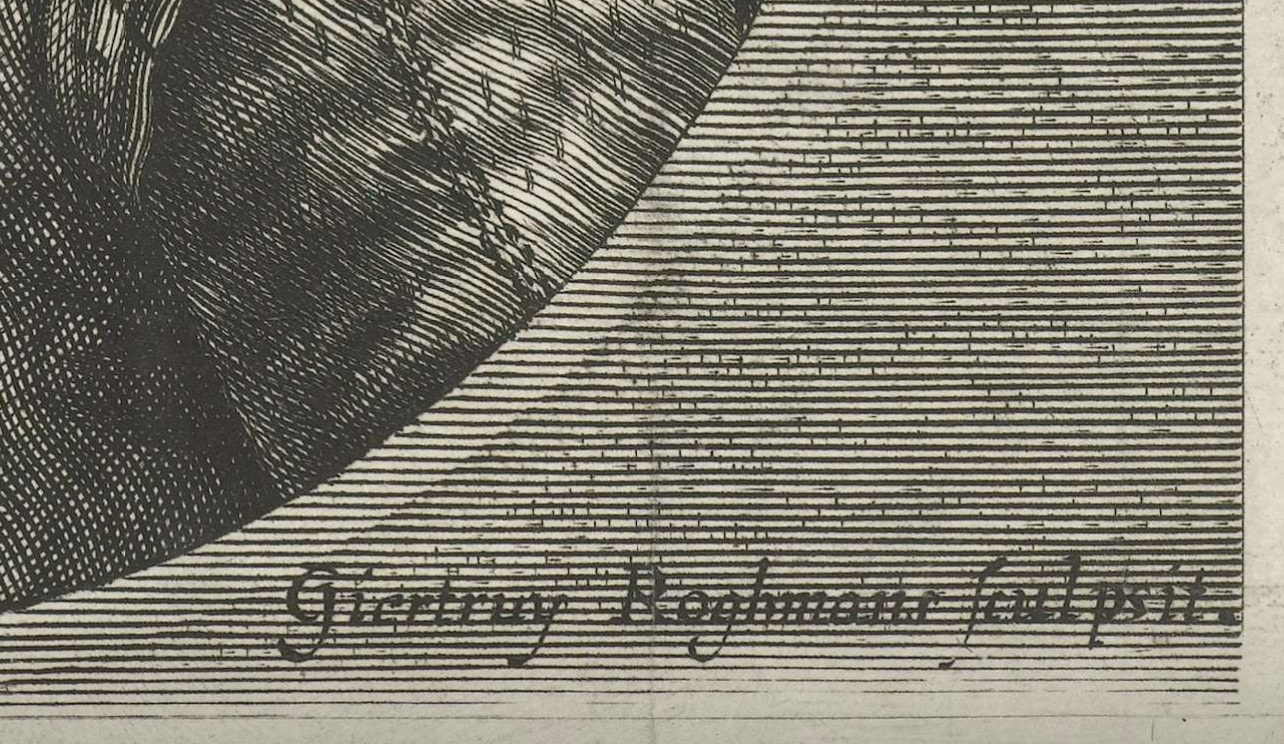

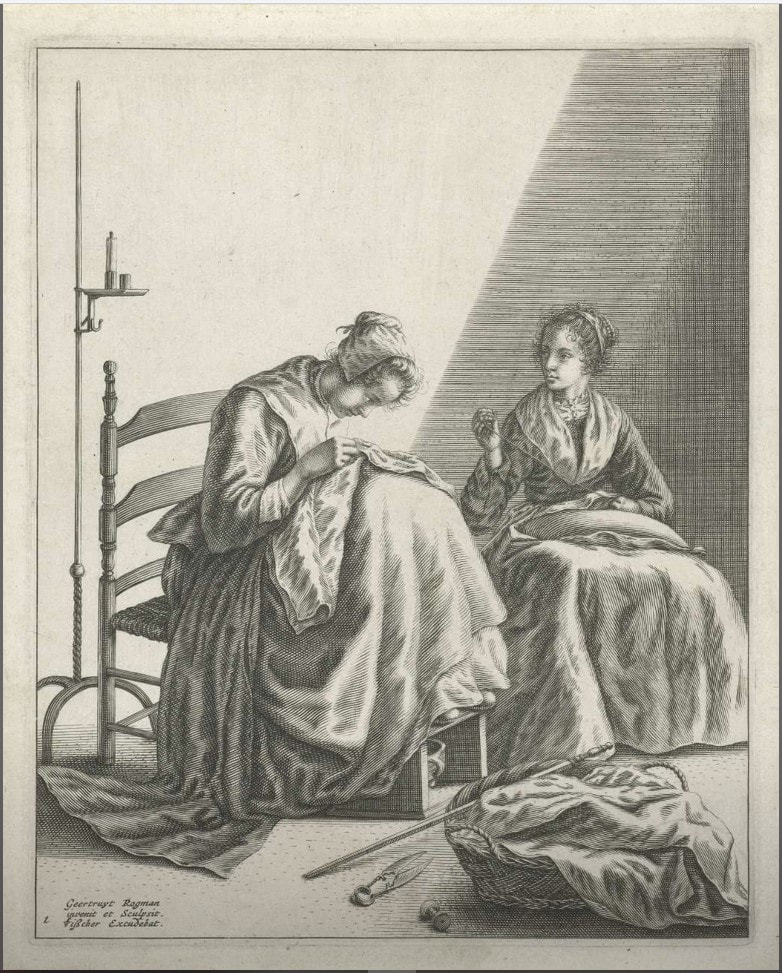

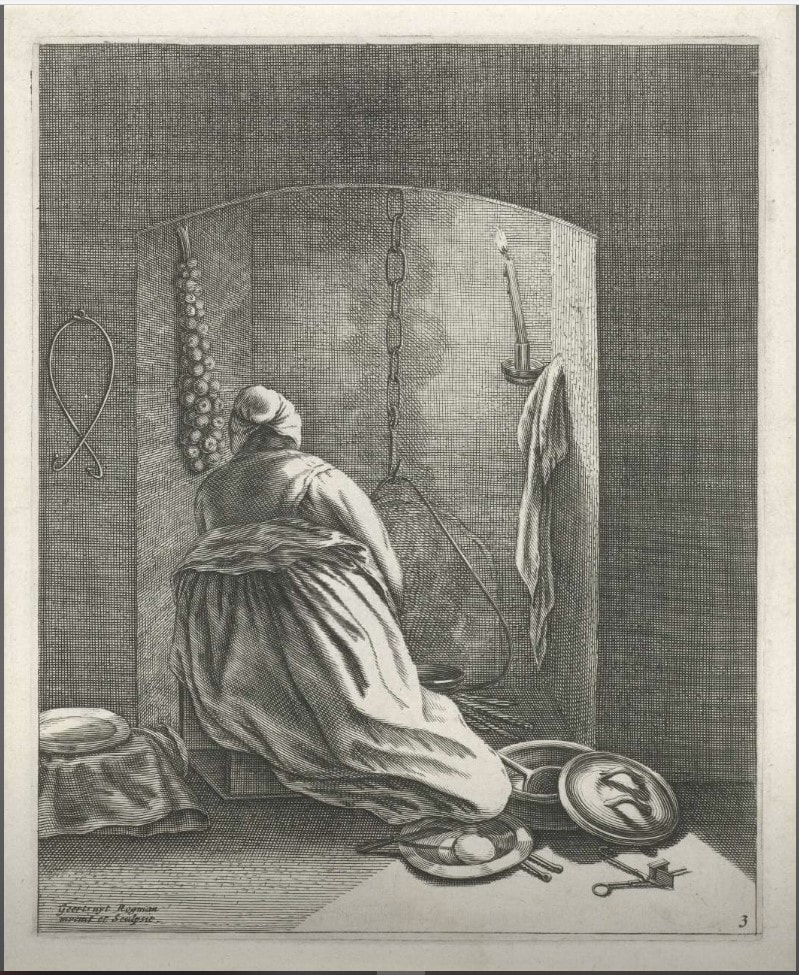

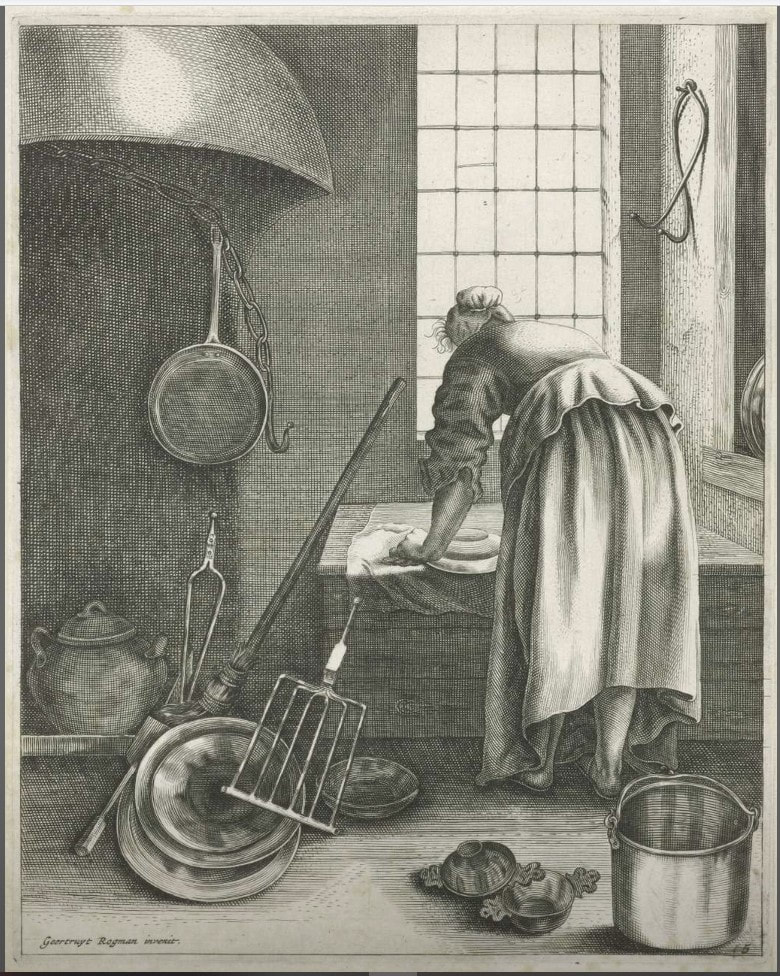

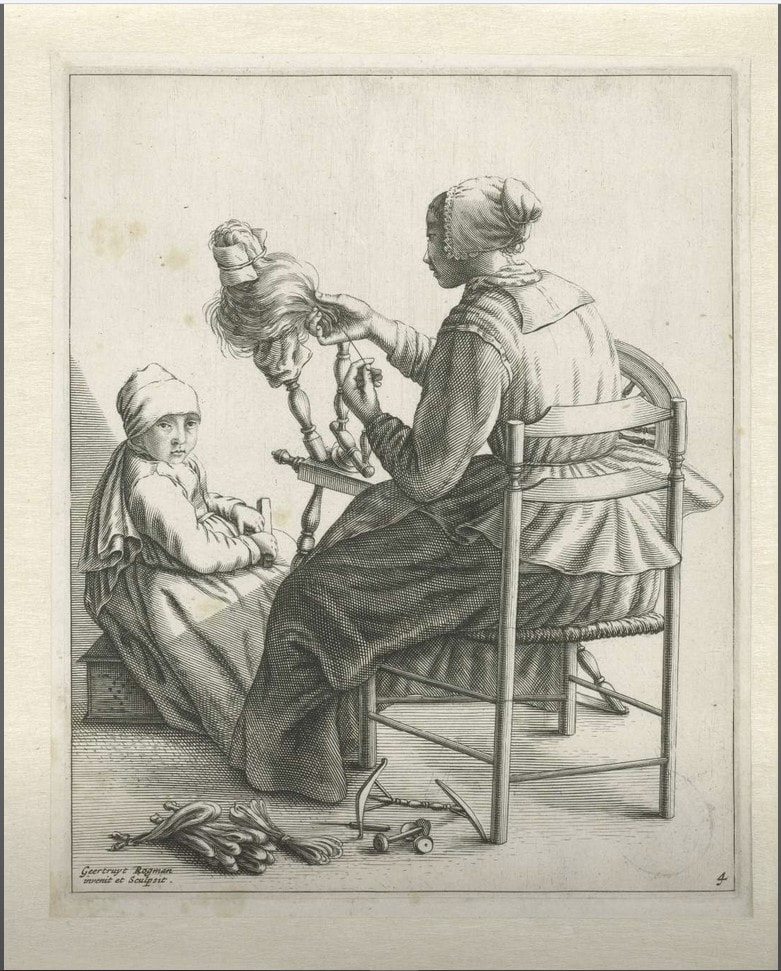

Geertruydt’s father, Hendrik Lambertsz. Roghman (1602–before 1657), was an engraver. Her mother Maritje’s father was Jacob Savery II (1593–c. 1627), a painter and etcher. Her great uncle was the Flemish painter and printmaker Roelant Savery (1576–1639), whose patron was Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612). Geertruydt’s brother Roelant (1627–1692) and sister Magdalena (1637–after 1669) were also artists and the three siblings worked with their father. As we’ve seen in our discussions of Diana Scultori and Elisabetta Sirani (see recent posts), women printmakers were frequently members of a larger artist family. Otherwise, it must have been difficult to access the world of print publishing. Roghman mostly made reproductive prints—meaning prints reproducing the compositions of other works, which can be paintings or even other prints. Her earliest known work is a portrait engraving of her great uncle Roelant, after a painting by Paulus Moreelse (1571–1638). With her brother Roelant, she made fourteen landscape etchings after his drawings. They were in their early twenties when they made these. But, Roghman is best known and celebrated for a set of five prints that are her own designs (not after some other artist’s paintings or prints) that show women engaged in daily household tasks. They are remarkable in their originality and banality. In four of them an anonymous woman is going about her day: ruffling some fabric, spinning yarn, cooking, cleaning cookware. In the fifth print, two women are sewing. Interestingly, in two of the prints, lone figures have their backs turned to the viewer. So why images of daily life rather than moralizing or religious lessons, you ask? The simple answer is that in Northern Europe (Germany, Holland, Flanders), an anti-Catholic movement was born in the sixteenth century. The Protestant movement (protest—get it?) prescribed that people did not need the Church as intercessor but they should instead form a more direct and personal relationship with God. This meant no images in churches, no religious paintings, no religious prints. (It’s more complicated than that, but you get the picture.) This anti-religious-imagery trend marked the rise of other subjects in art: portraits, still lifes, landscapes, scenes of daily life. With Roghman’s series of women doing daily tasks, we get even more of a sense of the reality of women’s daily lives. She was one of the few seventeenth-century Dutch artists to focus on ordinary women. As the Metropolitan Museum’s web site points out: “In comparing Roghman's images of household servants with those of [Gerrit] Dou and [Johannes] Vermeer, it is tempting to distinguish male and female points of view (as some critics have rather emphatically). Whatever the interpretation, it is important to bear in mind that Roghman's prints were intended for a broad art market, whereas Dou's famously expensive paintings (as opposed to the later prints after them) and The Milkmaid by Vermeer were made with individual collectors in mind.” Roghman’s prints were an abrupt departure from the religious imagery we had been covering in class up to that point. The figures are so ordinary that their meaning and importance was lost on the students. Only with context did they come to life. Of course, Tru was there to guide us every step of the way.

0 Comments

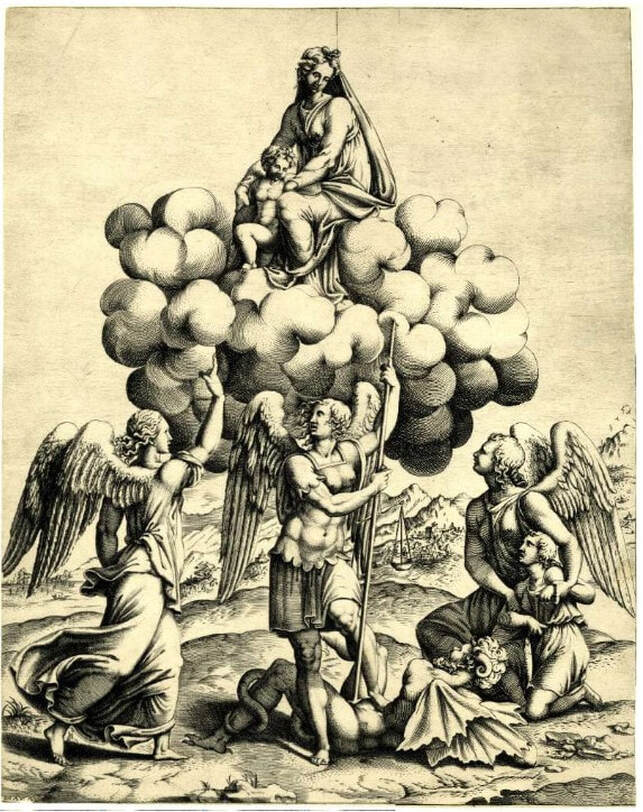

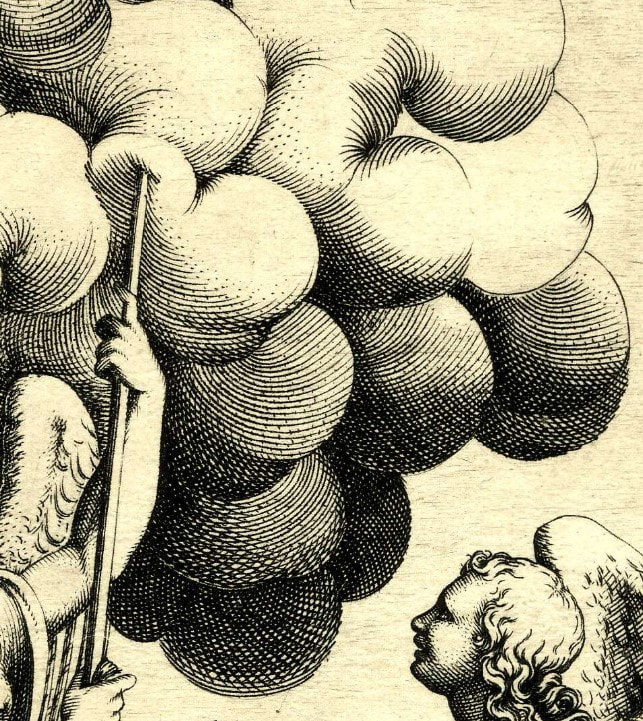

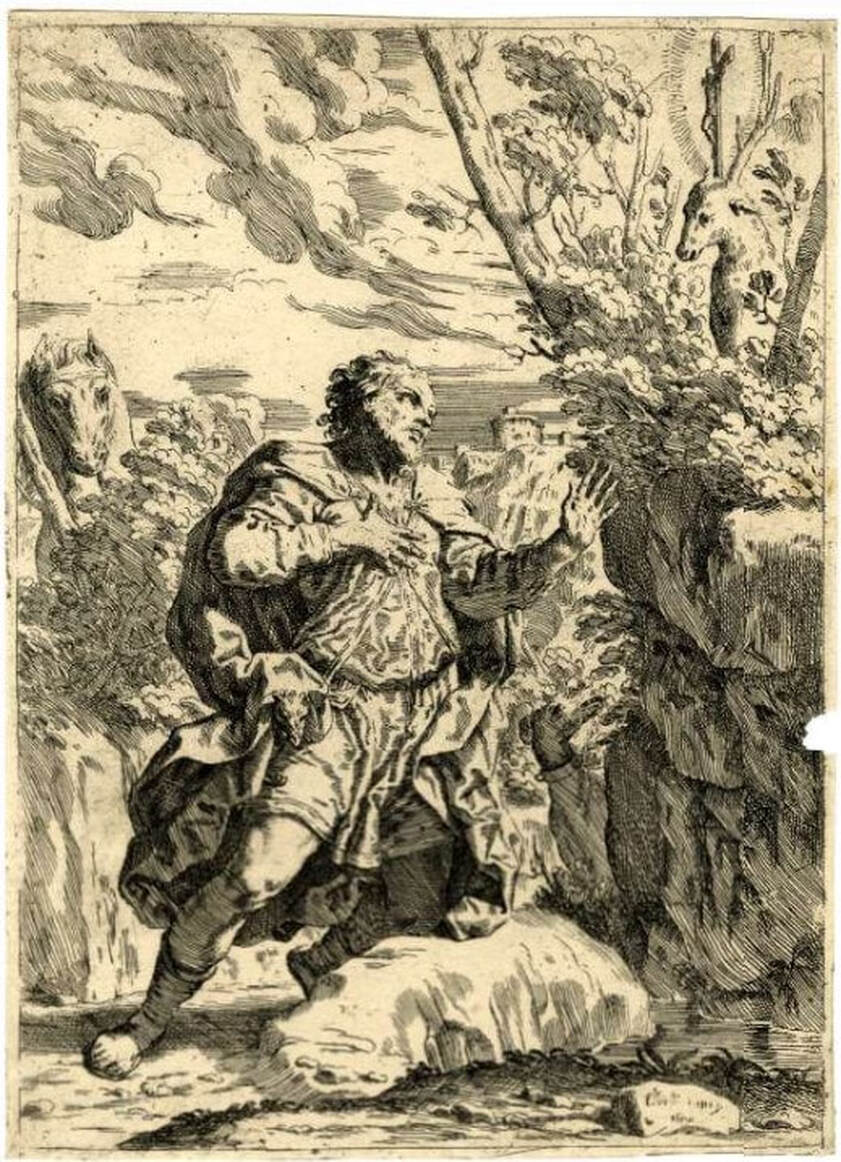

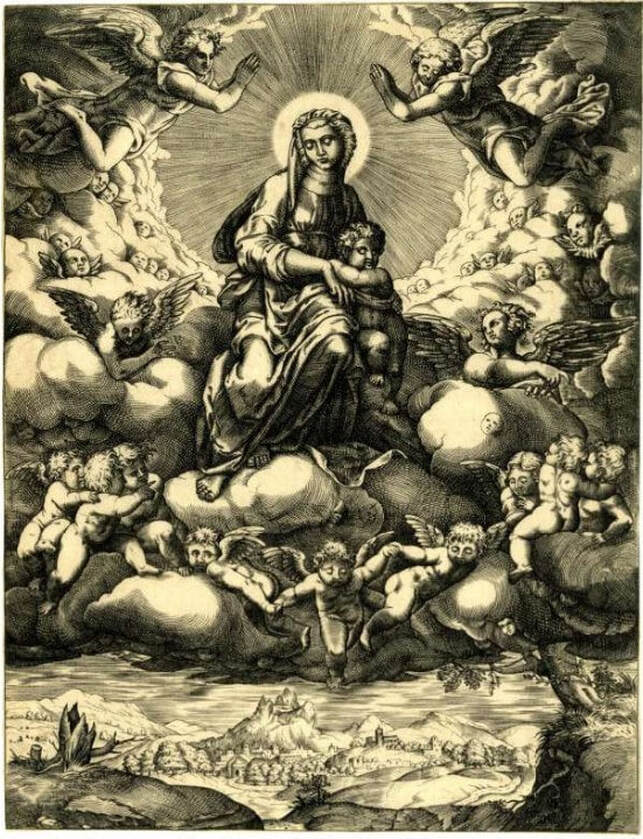

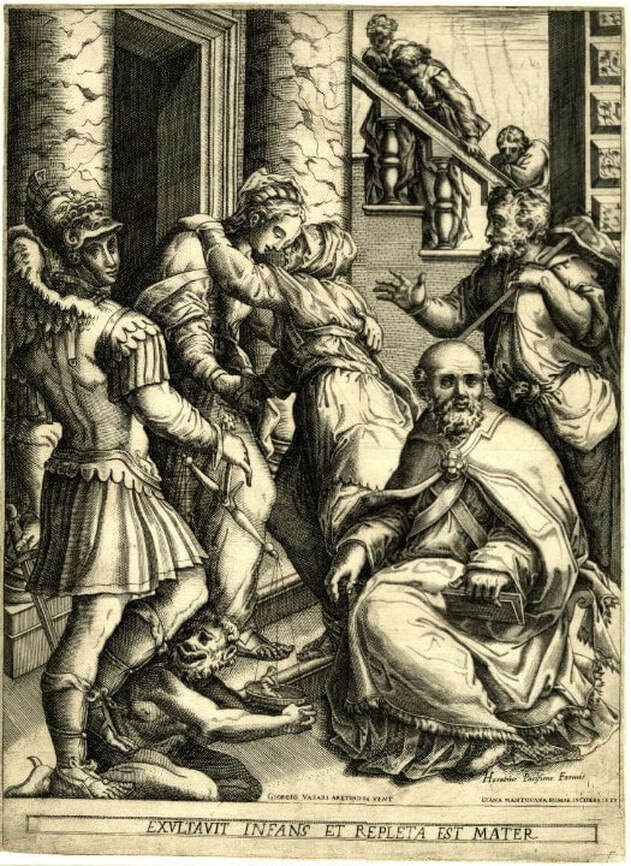

Ann Shafer “Why are there no great women artists?” was the main question tackled by Linda Nochlin in a 1971 essay that changed art history forever. In it, Nochlin didn’t dive into the lives of specific women, rather, she critiqued the systems, schools, and other institutions that were designed to discriminate against women. It was the beginning of a conversation that endures. Yes, there are few female printmakers recorded in the early history of Western printmaking. But does it follow that there aren’t any or is it that we just don’t know who they are? Today, please meet Elisabetta Sirani (Italian, 1638–1665), who produced an astonishing two hundred paintings and fifteen etchings before she died at the young age of twenty-seven. Born in Bologna, Sirani was the daughter of Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was principal assistant to the painter Guido Reni. When her father became ill, Sirani ran the print publishing business supporting the whole family. Luckily for future historians, she was mentored by one Carlo Malvasia, who became her biographer. She was painting professionally by the age of seventeen and she completed commissions for private patrons (usually small-scale devotional paintings) as well as for aristocratic patrons like Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici (these were large-scale religious and historical works). Sirani’s reputation for rapidly painting beautiful canvases drew skepticism as patrons believed her father must be helping her with production. Sirani countered these rumors by opening her studio to visitors to show that she alone was completing the paintings. (One can imagine a society’s shock that such a young artist could be so prolific, especially a female one. And yet, I’m rolling my eyes at their disbelief.) Apparently, Sirani taught more than a dozen young women who went on to become professional artists themselves (aside from her two sisters, I haven’t found a comprehensive list so far). All before age twenty-seven—impressive, indeed. Her touch reminds me of the prints of father and son Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo. Interestingly, G.B. was born in 1696, thirty years after Sirani died. Wonder if he knew her work somehow? All these prints are in the British Museum, which has an astonishingly deep collection of prints and drawings. (Check out each print’s accession number and note the year of acquisition, 1799. American collections were not even a spark in a collector’s eye). These works were acquired as part of the bequest of Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode (British, 1730–1799), a collector of books, drawings, prints, shells, and minerals (a classic eighteenth-century student of the Enlightenment). He was a trustee of the British Museum beginning in 1784, and upon his death in April 1799, his holdings entered the museum’s collection. The Cracherode bequest included forty-five hundred books, many of which are important examples of early printing, and the portfolios of prints included magnificent engravings by Dürer and etchings by Rembrandt and form the basis of the museum’s print collection. By the way, the British Museum’s works on paper collection includes 50,000 drawings and more than two million prints. And I thought 65,000 pieces of paper was a lot to wrangle. Ann Shafer In recognition of the one hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the nineteenth amendment granting women the right to vote, the BMA has just concluded its year of the woman during which it exhibited and acquired only work by female artists. I applaud the effort and am happy to see they have shown some terrific artists during 2020. It is pretty easy in contemporary art to find excellent female artists. Despite the fact that women still account for less than 50% of exhibitions across US museums, the problem is at least recognized. It is much harder to find huge numbers of women working in the early centuries of Western art—say, fourteenth through eighteenth centuries. In the early history of prints, when women artists are noted, most are members of a print and publishing family or are amateur artists. Remember, women were barred from art schools and institutions and there was a serious barrier to entry on multiple fronts. More research is emerging about these should-be-better-known artists. But it takes time and a lot of work. In the next few posts I want to introduce you to a few early female printmakers. Today, please meet Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588). Part of the reason we know about Scultori’s work at all is that she signed her prints, which she did from her earliest known composition, The Continence of Scipio, 1542, to her last. The existence of this first dated print has thrown into question her birth date, which is usually noted as 1536. A birth date in the late 1520s is more likely given the math--most of us would agree that accomplishing an engraving at age six is unlikely, no matter how good she was. Scultori was one of four children of Giovanni Battista Scultori, who lived and operated a print workshop in Mantua. She learned printmaking in her father’s studio and executed a number of prints reproducing the compositions of several artists including Giulio Romano, who was a friend and neighbor. Romano was a pupil of Raphael and was the official artist of Duke Federico Gonzaga of Mantua. Scultori's prints helped spread Romano's renown far and wide. Scultori received her first public recognition as an engraver in Giorgio Vasari's second edition of Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects) in 1568, an early codification of Italian art history. In it Vasari talks about meeting the artist and her father on a trip to Mantua: "To Giovanbattista Mantovano, an engraver of prints and an excellent sculptor, whom we have spoken of, in the Vita of Giulio Romano and that of Marcantonio Bolognese, two sons were born, who engrave prints on copper divinely; and what is more wondrous, a daughter named Diana, who also engraves very well, which is a wondrous thing: and I who saw her, a very young and gracious young girl, and her works which are very beautiful, was astounded." This is a huge deal. Scultori engraved some sixty-two prints (that we know of), mainly of religious and mythological subjects. With her architect husband, Francesco Capriani da Volterra, she moved to Rome in 1575, where she received a Papal Privilege to make and market her own work. From the middle of the sixteenth century print publishers applied for privileges for specific prints or for all of their publications, which gave a legal base for prosecution in case of breach of the privilege. It must have been remarkable for the Pope to give Scultori the privilege on all her prints, which she signed “Diana” or “Diana Mantuana” (indicating she hailed from Mantua). Later, she married another architect, Giulio Pelosi, after her first husband died in 1594. She herself died in 1612. I imagine we would know absolutely nothing about her if she had not insisted on signing her works. Did she understand that any unsigned work would be assumed to be by a man? I am guessing she did, and that that confidence was encouraged by her father and brothers in the family printshop. I would love to have been a fly on the wall in that workshop. Don’t miss how she articulate those clouds in the last detail: stylized and hilarious, in the best way.  Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588), after Giulio Romano (Italian, c. 1499–1546). The archangels Michael, Gabriel and Raphael adoring the Virgin and Child who occur above seated on a cloud, 1547–1612. Engraving. Sheet (trimmed to platemark): 340 x 270 mm. British Museum: Bequest of Sir Hans Sloane, 1799, V,8.12.  [DETAIL] Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588), after Giulio Romano (Italian, c. 1499–1546). The archangels Michael, Gabriel and Raphael adoring the Virgin and Child who occur above seated on a cloud, 1547–1612. Engraving. Sheet (trimmed to platemark): 340 x 270 mm. British Museum: Bequest of Sir Hans Sloane, 1799, V,8.12. Ann Shafer When I started in the print department in fall 2005, I got a request to host a Maryland Institute College of Art History of Prints (HoP) class for multiple visits. The professor had taught the class before and had an already established lists of objects. Even being new to the task, I was surprised to realize the breadth of the plan. For each of six visits we pulled out between eighty and one hundred prints starting with Master ES and ending with yesterday. While those classes were a lot of work, they were so rewarding. The immense impact of HoP on hundreds of young artists is due solely to professor Tru Ludwig who is not only a gifted art historian, but also is a practicing printmaker with some badass technical chops. We clicked from the start and taught HoP together fifteen times between 2005 and 2017. In my time in the print room, no other teachers made as powerful a use of the collection.

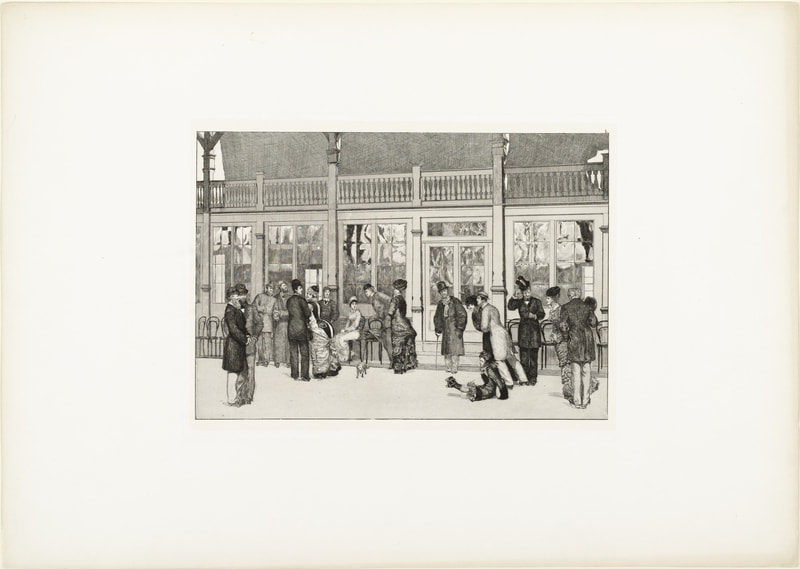

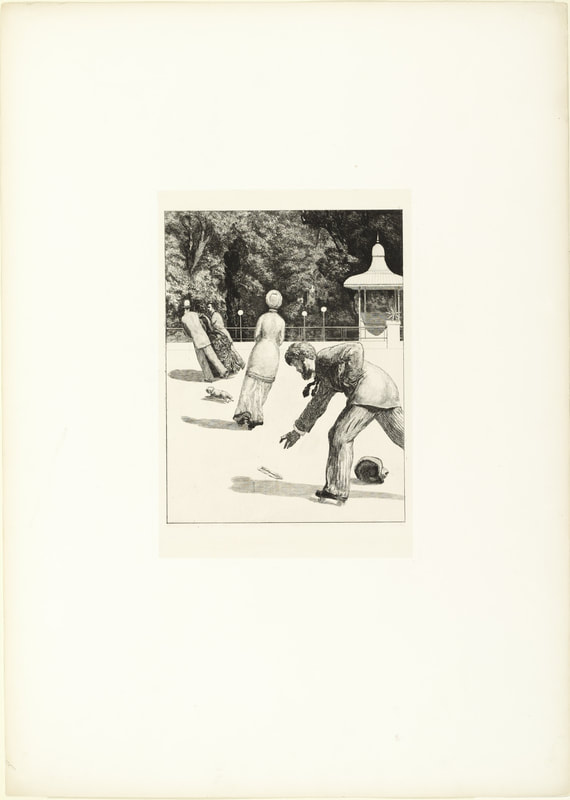

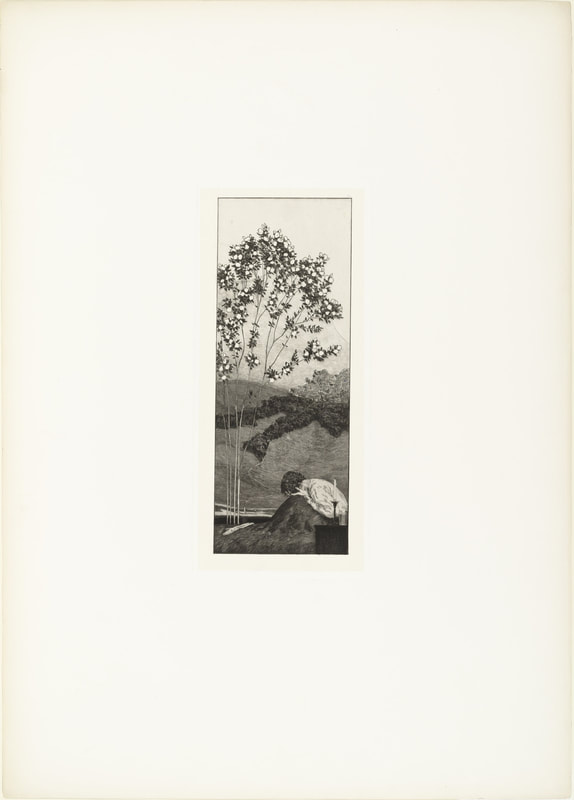

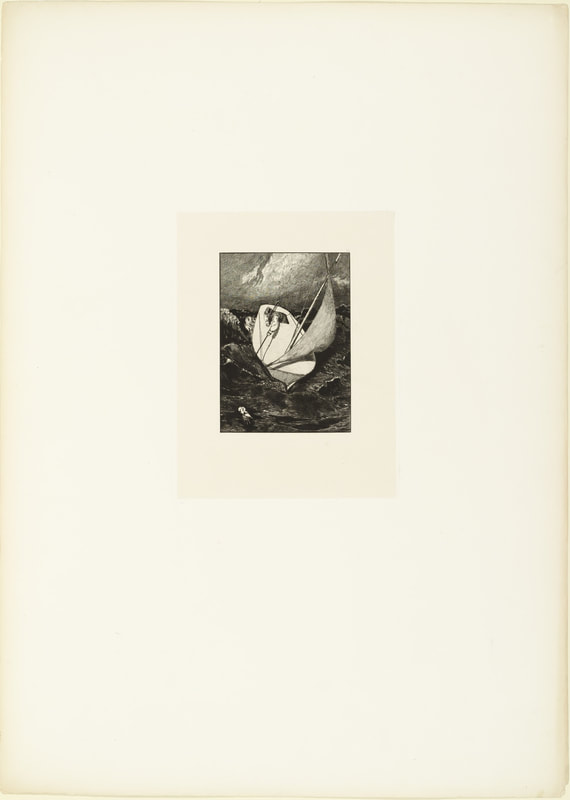

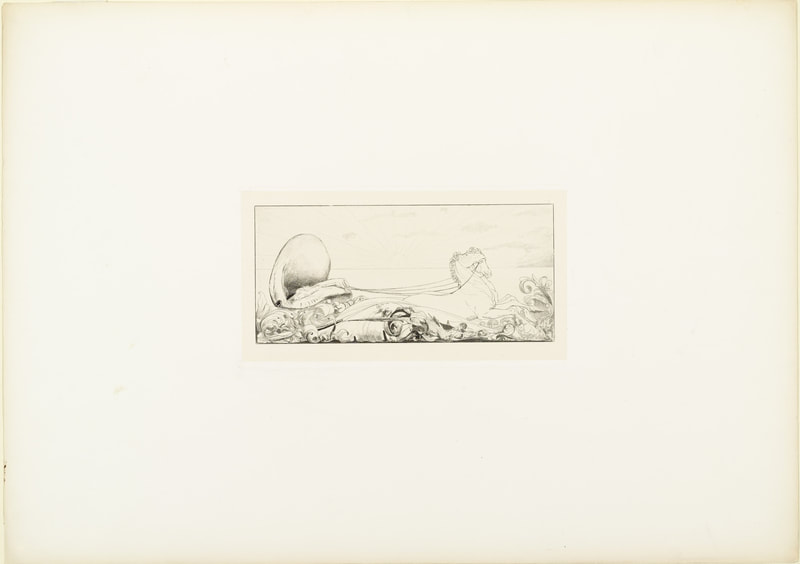

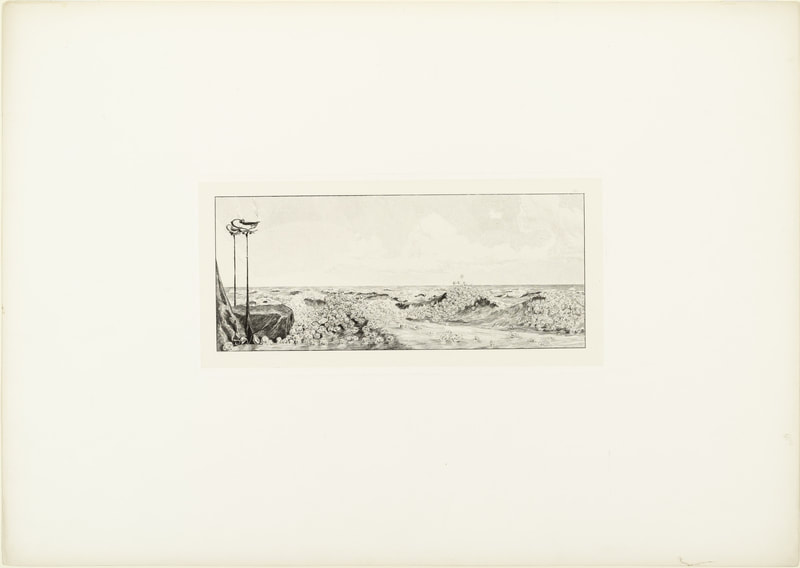

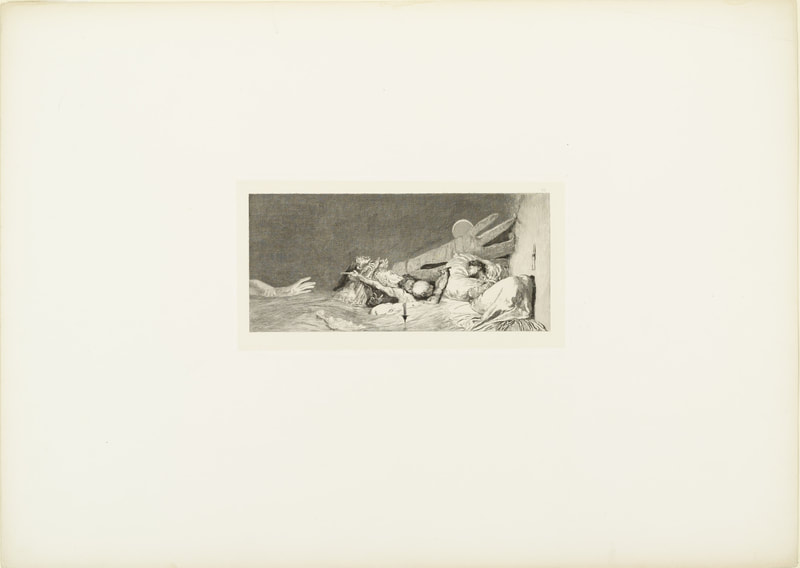

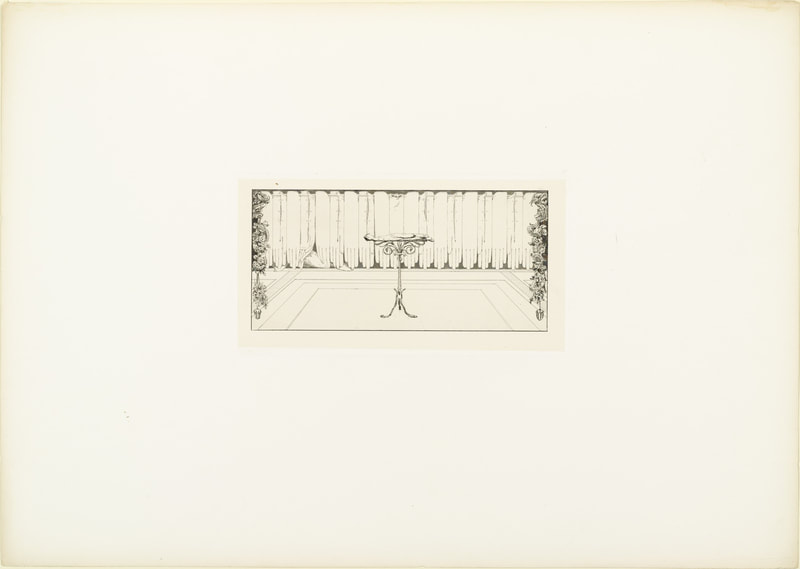

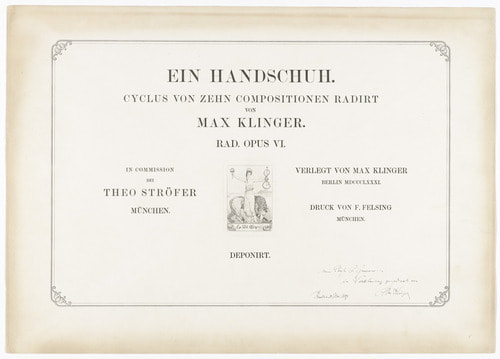

I had never taken a history of prints class (exactly how many colleges offer one?), and with Tru, I had a front row seat to the best teaching I’d ever seen. What does it take to engage twenty-five art students, some of whom think they don’t need to learn anything? It takes a person whose passion is contagious and whose performance is energetic, full of prime historical and technical information, and who encourages students to get up close and personal with the prints themselves. Print nerds know that looking at prints out of their frames is really the only way to get close enough to see what is going on in line quality, tiny details, and textures. The combination of excellent teaching and in-person contact with actual objects is just the best. Tru shines when he starts talking about a time period, movement, or particular artist and gets on a roll. Every semester there was at least one spiel that gave me goosebumps or got me teary-eyed, and more than one that made everyone laugh. After Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, and everyone in between, and having seen hundreds of prints, we’d finally get to the late-nineteenth century. Most of the material from this period is focused on France, but a sudden detour to Germany introduced Max Klinger and his 1881 portfolio, A Glove (Ein Handschuh), to the class. Klinger (1857–1920) was a bit of an outsider. He created visions from his mind’s eye that presaged twentieth-century thinking about the subconscious and dreams before it was a thing. His work influenced surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico, as well as Käthe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch. Of the thirteen portfolios Klinger published during his lifetime, his first is a favorite. It is based on a set of drawings, Fantasies on a Found Glove (Phantasien über einen gefundenen Handschuh), which was exhibited in 1878 at the Berlin Royal Academy of the Arts' annual exhibition. (He was twenty-one years old.) Encouraged by art dealer and engraver Hermann Sagert, Klinger published the set of etchings as a portfolio two years later in 1881. A Glove, Opus VI (Ein Handschuh, Opus VI) features ten etchings and a title page that follows a dream/nightmare sequence of a lost ladies’ glove. First picked up at a skating rink, it becomes an obsession for the central character (Klinger himself) and haunts his waking and sleeping moments. The sexual connotations of such an object are obvious, and Tru’s description had all of us tittering with laughter. The portfolio was always a hit with the class. MoMA’s Heather Hess sums up the portfolio’s narrative nicely: “Klinger meticulously depicts the real and the imaginary with hallucinatory clarity, casting himself as protagonist. At a skating rink in Berlin, Klinger is seen eyeing a beautiful young woman; he swoops down to retrieve her dropped glove. This intimate and potently sexualized object triggers a series of elaborate visions of longing and loss, conveyed through dreamlike distortions of scale and jarring juxtapositions. As desire threatens to engulf Klinger, the fetishized glove takes on a life of its own. It assumes the attributes of Venus, born of sea foam and driving a shell chariot. An outsize version torments him in his sleep, recalling Francisco de Goya's prints. Klinger's grasp on the glove remains elusive, and a fantastic creature finally spirits the object away.” (https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/object/object_objid-64063.html) The portfolio’s popularity is clear; after the first publication, it was issued in several subsequent editions, including one posthumously (meaning after Klinger’s death). This is the publication sequence: the first edition was published in 1881 in an edition of twenty-five; a second edition was published a year later as Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs in an unknown quantity; both a third (1883) and fourth (1892) edition were published in an unknown quantity; the fifth edition was posthumously published in 1924, as Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs by Verlag von Gertrud Hartmann-Klinger in an edition of approximately one hundred. Knowing all this becomes important when it comes to value and marketability. Obviously, it is preferable to have the earliest set. But would I buy a posthumous set for myself if I came across one? Hell yes. It's such an odd, fantastical sequence, and is all the more remarkable because it dates to the early 1880s, comes out of Germany, and is executed by a twenty-something artist. It makes me wonder about the exact nature of creativity and imagination. I mean, from whence do these kinds of visions come? And who is bold enough to make them into a multiple, collectible set of gorgeous etchings? Tru’s presentation of Ein Handschuh was a highlight every semester. I’d wager that former students (we call them HoPsters) would agree that it was indeed memorable. Any HoPster alums want to chime in? |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed