Ann Shafer When I started in the print department in fall 2005, I got a request to host a Maryland Institute College of Art History of Prints (HoP) class for multiple visits. The professor had taught the class before and had an already established lists of objects. Even being new to the task, I was surprised to realize the breadth of the plan. For each of six visits we pulled out between eighty and one hundred prints starting with Master ES and ending with yesterday. While those classes were a lot of work, they were so rewarding. The immense impact of HoP on hundreds of young artists is due solely to professor Tru Ludwig who is not only a gifted art historian, but also is a practicing printmaker with some badass technical chops. We clicked from the start and taught HoP together fifteen times between 2005 and 2017. In my time in the print room, no other teachers made as powerful a use of the collection.

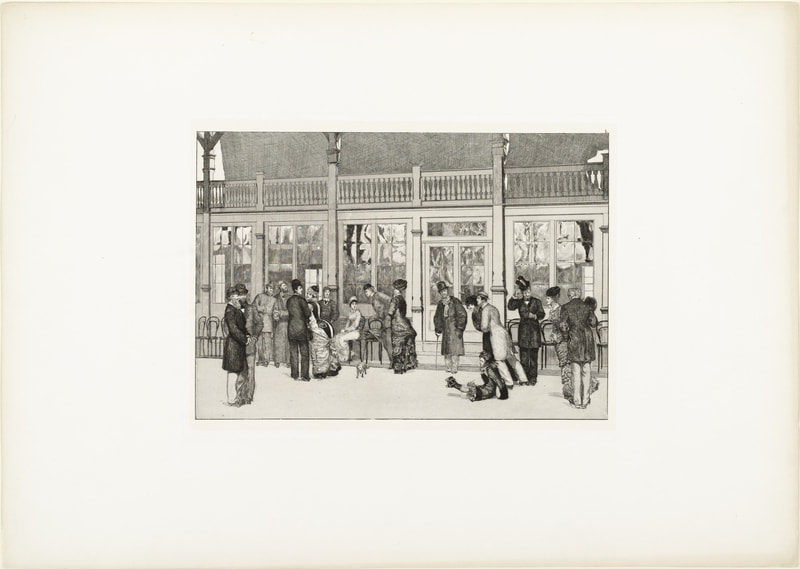

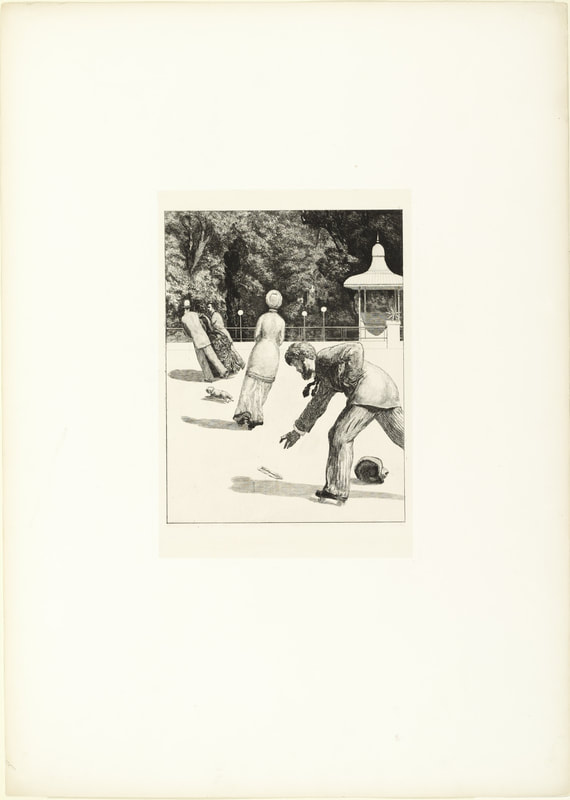

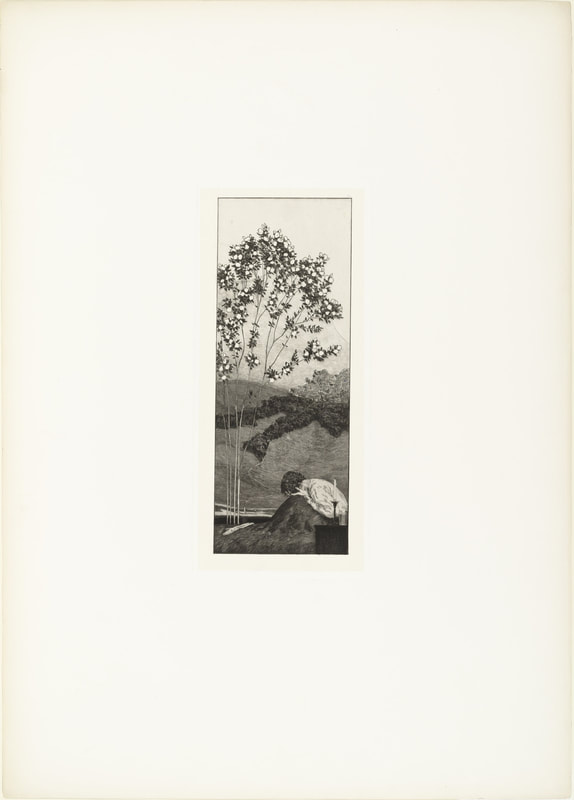

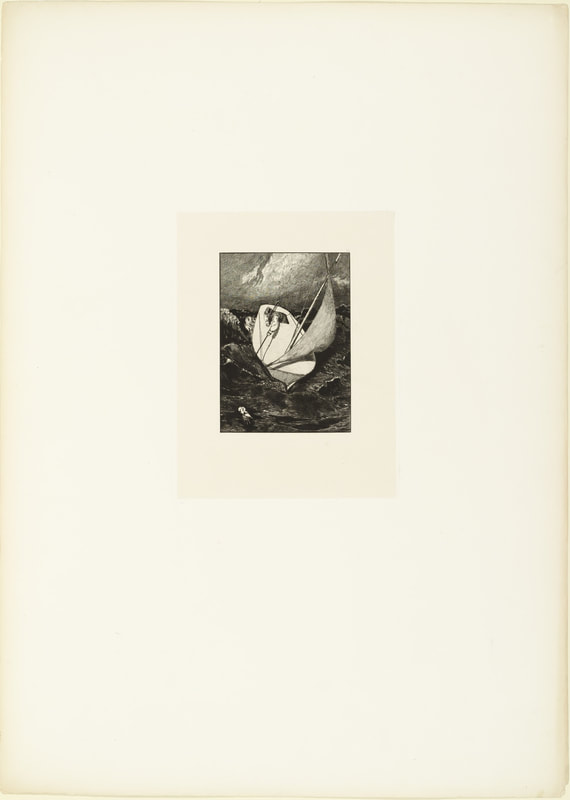

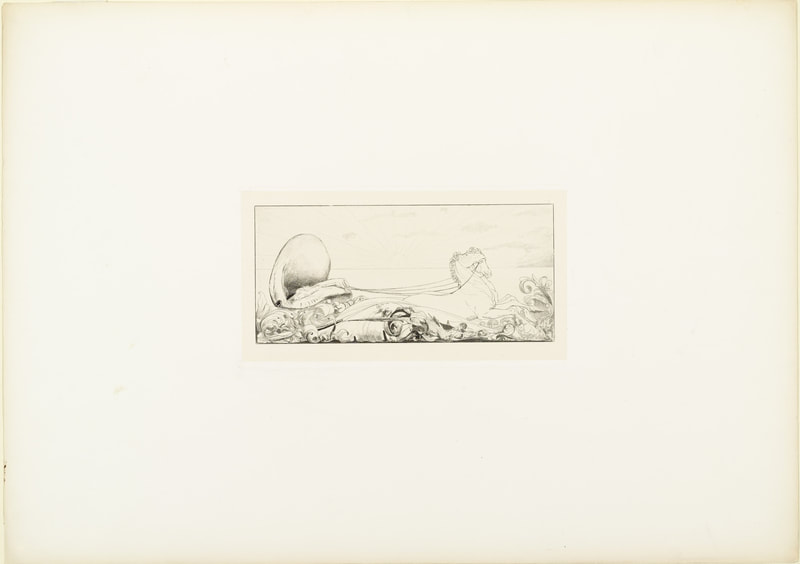

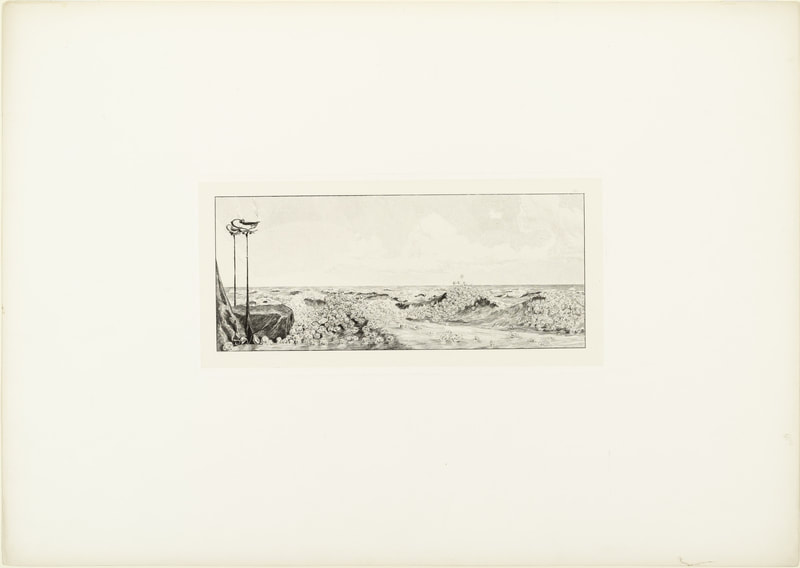

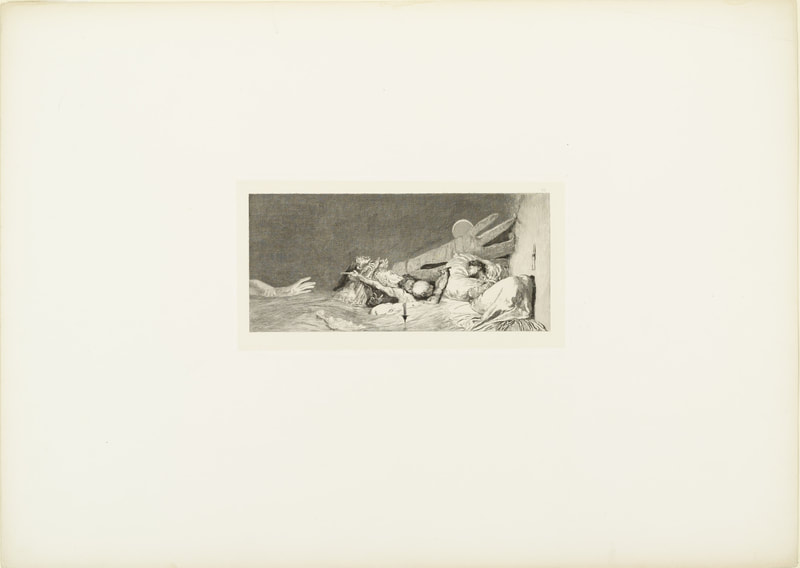

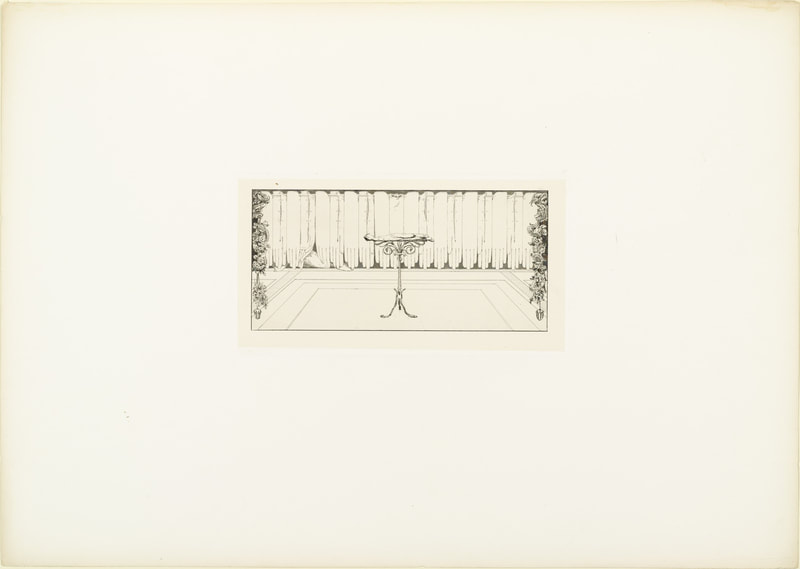

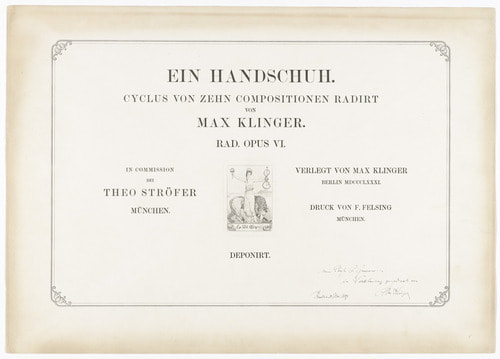

I had never taken a history of prints class (exactly how many colleges offer one?), and with Tru, I had a front row seat to the best teaching I’d ever seen. What does it take to engage twenty-five art students, some of whom think they don’t need to learn anything? It takes a person whose passion is contagious and whose performance is energetic, full of prime historical and technical information, and who encourages students to get up close and personal with the prints themselves. Print nerds know that looking at prints out of their frames is really the only way to get close enough to see what is going on in line quality, tiny details, and textures. The combination of excellent teaching and in-person contact with actual objects is just the best. Tru shines when he starts talking about a time period, movement, or particular artist and gets on a roll. Every semester there was at least one spiel that gave me goosebumps or got me teary-eyed, and more than one that made everyone laugh. After Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, and everyone in between, and having seen hundreds of prints, we’d finally get to the late-nineteenth century. Most of the material from this period is focused on France, but a sudden detour to Germany introduced Max Klinger and his 1881 portfolio, A Glove (Ein Handschuh), to the class. Klinger (1857–1920) was a bit of an outsider. He created visions from his mind’s eye that presaged twentieth-century thinking about the subconscious and dreams before it was a thing. His work influenced surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico, as well as Käthe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch. Of the thirteen portfolios Klinger published during his lifetime, his first is a favorite. It is based on a set of drawings, Fantasies on a Found Glove (Phantasien über einen gefundenen Handschuh), which was exhibited in 1878 at the Berlin Royal Academy of the Arts' annual exhibition. (He was twenty-one years old.) Encouraged by art dealer and engraver Hermann Sagert, Klinger published the set of etchings as a portfolio two years later in 1881. A Glove, Opus VI (Ein Handschuh, Opus VI) features ten etchings and a title page that follows a dream/nightmare sequence of a lost ladies’ glove. First picked up at a skating rink, it becomes an obsession for the central character (Klinger himself) and haunts his waking and sleeping moments. The sexual connotations of such an object are obvious, and Tru’s description had all of us tittering with laughter. The portfolio was always a hit with the class. MoMA’s Heather Hess sums up the portfolio’s narrative nicely: “Klinger meticulously depicts the real and the imaginary with hallucinatory clarity, casting himself as protagonist. At a skating rink in Berlin, Klinger is seen eyeing a beautiful young woman; he swoops down to retrieve her dropped glove. This intimate and potently sexualized object triggers a series of elaborate visions of longing and loss, conveyed through dreamlike distortions of scale and jarring juxtapositions. As desire threatens to engulf Klinger, the fetishized glove takes on a life of its own. It assumes the attributes of Venus, born of sea foam and driving a shell chariot. An outsize version torments him in his sleep, recalling Francisco de Goya's prints. Klinger's grasp on the glove remains elusive, and a fantastic creature finally spirits the object away.” (https://www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/object/object_objid-64063.html) The portfolio’s popularity is clear; after the first publication, it was issued in several subsequent editions, including one posthumously (meaning after Klinger’s death). This is the publication sequence: the first edition was published in 1881 in an edition of twenty-five; a second edition was published a year later as Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs in an unknown quantity; both a third (1883) and fourth (1892) edition were published in an unknown quantity; the fifth edition was posthumously published in 1924, as Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs by Verlag von Gertrud Hartmann-Klinger in an edition of approximately one hundred. Knowing all this becomes important when it comes to value and marketability. Obviously, it is preferable to have the earliest set. But would I buy a posthumous set for myself if I came across one? Hell yes. It's such an odd, fantastical sequence, and is all the more remarkable because it dates to the early 1880s, comes out of Germany, and is executed by a twenty-something artist. It makes me wonder about the exact nature of creativity and imagination. I mean, from whence do these kinds of visions come? And who is bold enough to make them into a multiple, collectible set of gorgeous etchings? Tru’s presentation of Ein Handschuh was a highlight every semester. I’d wager that former students (we call them HoPsters) would agree that it was indeed memorable. Any HoPster alums want to chime in?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed