Ann ShaferIf ever I turned my attention to making art instead of writing about it, I would pull out my watercolors and brushes and head outdoors. It’s hard to imagine a world when that wasn’t possible—but it wasn’t so long ago that the first paints in tubes became commercially available. The first premixed watercolors were introduced to the market in England in the 1760s, but it wasn’t until the 1840s that those little tubes we know today were invented.

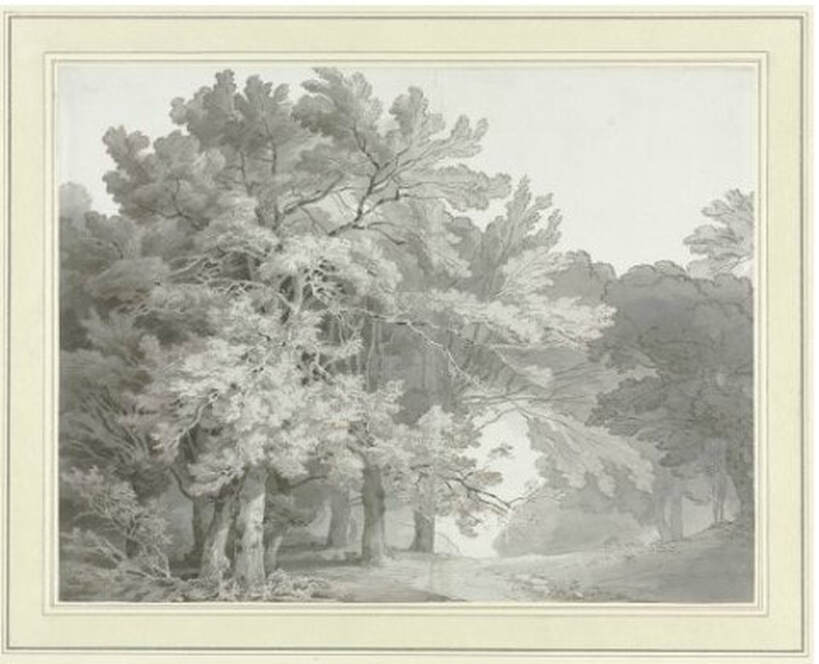

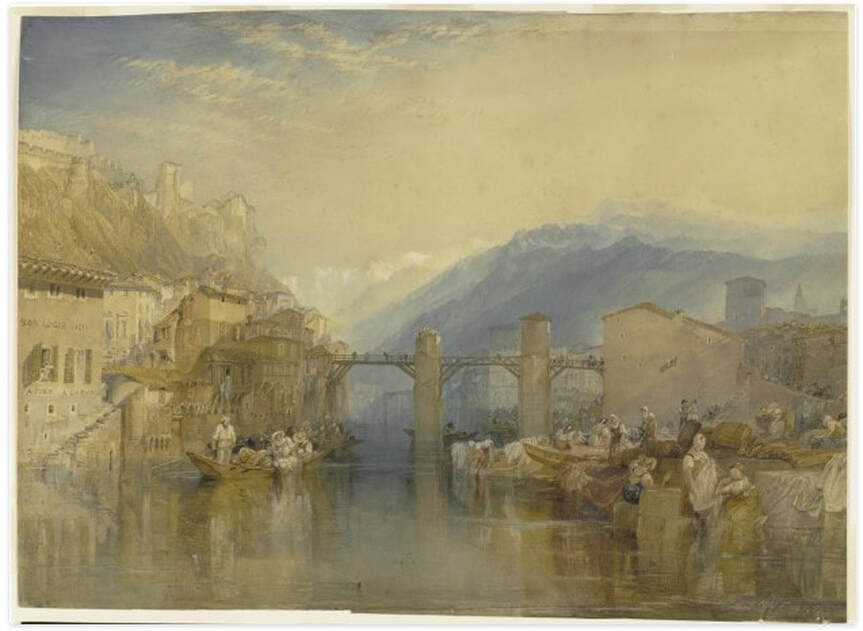

The proliferation of watercolor landscapes in England in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was due in no small part to the introduction of those premixed watercolor paints. Artists began to experiment with the medium and test the boundaries of what could be accomplished. Soon these works found their way into the annual exhibitions of the English Royal Academy, but they were so marginalized that a group of artists split from the Academy in 1804 to establish the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. The goal of this new Society was to place watercolors on an equal footing with oil paintings, and artists responded by creating large-scale, highly finished watercolors displayed in elaborate gold frames. The Baltimore Museum of Art is fortunate to have an example of one of these presentation watercolors by Britain’s favorite son, Joseph Mallord William Turner. In contrast to the highly finished exhibition watercolors, many artists created more intimate works in the same medium. Artists went outdoors with sketchbooks and paints to test their skills at portraying the landscape. One such work from a sketchbook (notice the crease down the center) is a favorite acquisition. The artist is John White Abbott, a country surgeon and apothecary from Exeter, who as an amateur artist painted for his own enjoyment (the term amateur indicates only that the artist did not earn money making art, but is no indication of a lack of talent). After inheriting an estate from his uncle, he was able to devote himself full time to painting. Abbott probably drew A Path through the Woods first in graphite pencil on the spot, and then returned to his studio to finish the work with gray washes and pen and brown ink. I continue to be amazed at the quality of light through the dappled foliage painted with just gray and brown. In fact, the execution is so masterful that I see this monochromatic scene in full color. In addition, the peacefulness of the scene always transports me to somewhere else. For me, this work is a figurative and literal breath of fresh air. John White Abbott (English, 1763‑1851) A Path through the Woods, c. 1785‑1795. Pen and brown and gray ink with brush and gray ink over graphite Sheet: 256 x 335 mm. (10 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased as the gift of Rhoda Oakley, Baltimore, BMA 2008.9 Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, 1775‑1851) Grenoble Bridge, c. 1824. Transparent and opaque watercolor with scraping over traces of graphite Sheet: 530 x 718 mm. (20 7/8 x 28 1/4 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchased with exchange funds from Nelson and Juanita Greif Gutman Collection, BMA 1968.28

0 Comments

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed