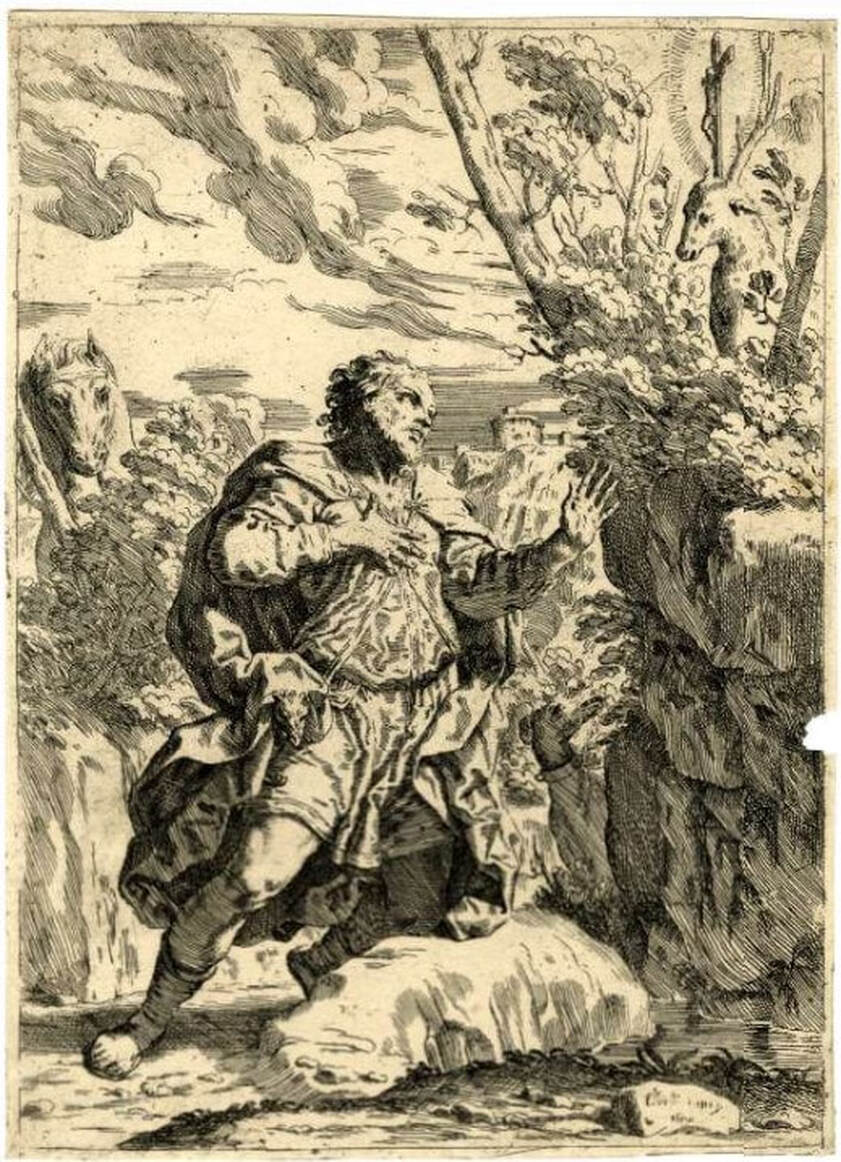

Ann Shafer “Why are there no great women artists?” was the main question tackled by Linda Nochlin in a 1971 essay that changed art history forever. In it, Nochlin didn’t dive into the lives of specific women, rather, she critiqued the systems, schools, and other institutions that were designed to discriminate against women. It was the beginning of a conversation that endures. Yes, there are few female printmakers recorded in the early history of Western printmaking. But does it follow that there aren’t any or is it that we just don’t know who they are? Today, please meet Elisabetta Sirani (Italian, 1638–1665), who produced an astonishing two hundred paintings and fifteen etchings before she died at the young age of twenty-seven. Born in Bologna, Sirani was the daughter of Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was principal assistant to the painter Guido Reni. When her father became ill, Sirani ran the print publishing business supporting the whole family. Luckily for future historians, she was mentored by one Carlo Malvasia, who became her biographer. She was painting professionally by the age of seventeen and she completed commissions for private patrons (usually small-scale devotional paintings) as well as for aristocratic patrons like Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici (these were large-scale religious and historical works). Sirani’s reputation for rapidly painting beautiful canvases drew skepticism as patrons believed her father must be helping her with production. Sirani countered these rumors by opening her studio to visitors to show that she alone was completing the paintings. (One can imagine a society’s shock that such a young artist could be so prolific, especially a female one. And yet, I’m rolling my eyes at their disbelief.) Apparently, Sirani taught more than a dozen young women who went on to become professional artists themselves (aside from her two sisters, I haven’t found a comprehensive list so far). All before age twenty-seven—impressive, indeed. Her touch reminds me of the prints of father and son Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo. Interestingly, G.B. was born in 1696, thirty years after Sirani died. Wonder if he knew her work somehow? All these prints are in the British Museum, which has an astonishingly deep collection of prints and drawings. (Check out each print’s accession number and note the year of acquisition, 1799. American collections were not even a spark in a collector’s eye). These works were acquired as part of the bequest of Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode (British, 1730–1799), a collector of books, drawings, prints, shells, and minerals (a classic eighteenth-century student of the Enlightenment). He was a trustee of the British Museum beginning in 1784, and upon his death in April 1799, his holdings entered the museum’s collection. The Cracherode bequest included forty-five hundred books, many of which are important examples of early printing, and the portfolios of prints included magnificent engravings by Dürer and etchings by Rembrandt and form the basis of the museum’s print collection. By the way, the British Museum’s works on paper collection includes 50,000 drawings and more than two million prints. And I thought 65,000 pieces of paper was a lot to wrangle.

1 Comment

|

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed