Ann ShaferIs the Enlightenment really the Endarkenment? It’s one thing to strive to understand and organize all human knowledge, and it is another thing to use that knowledge to justify the enslavement of a people and the subjugation of women. Stay with me here.

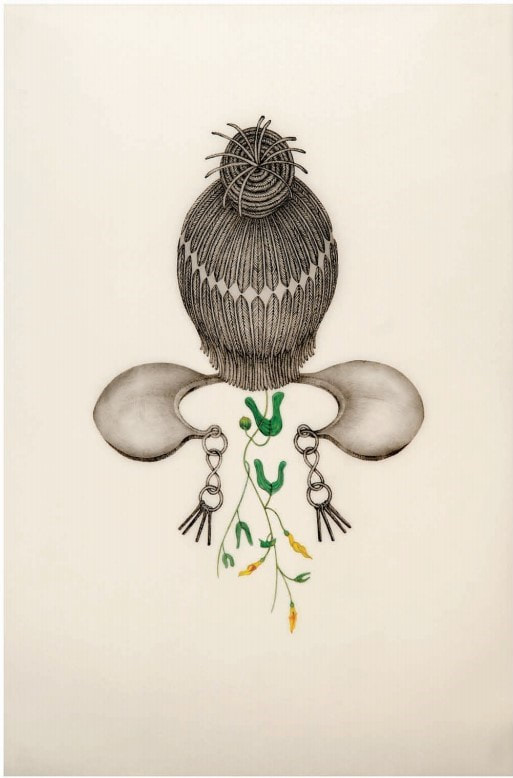

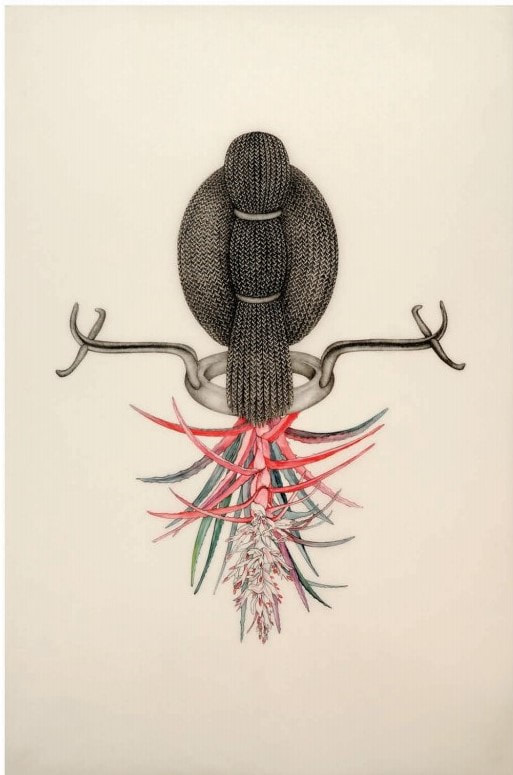

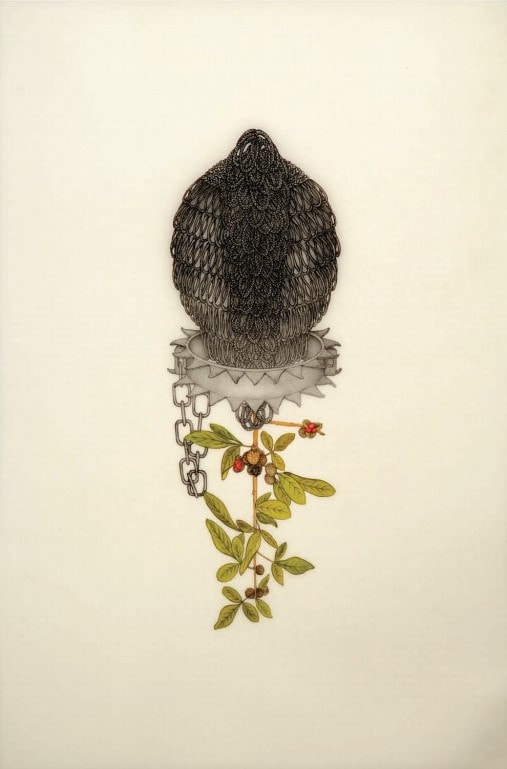

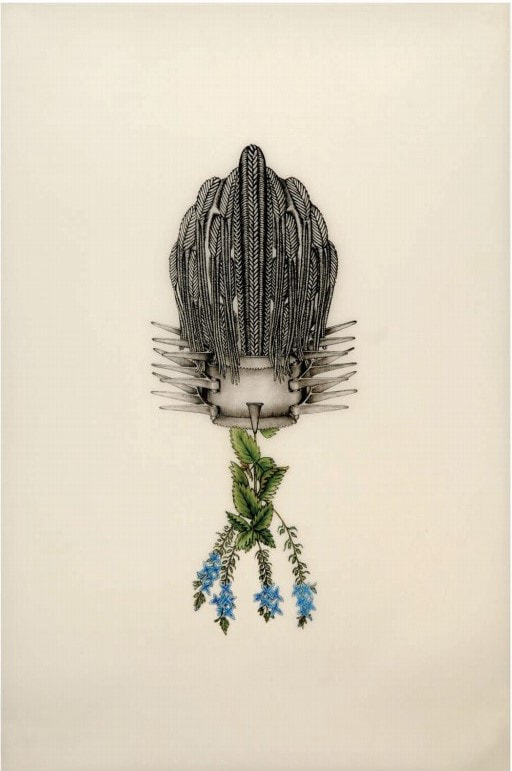

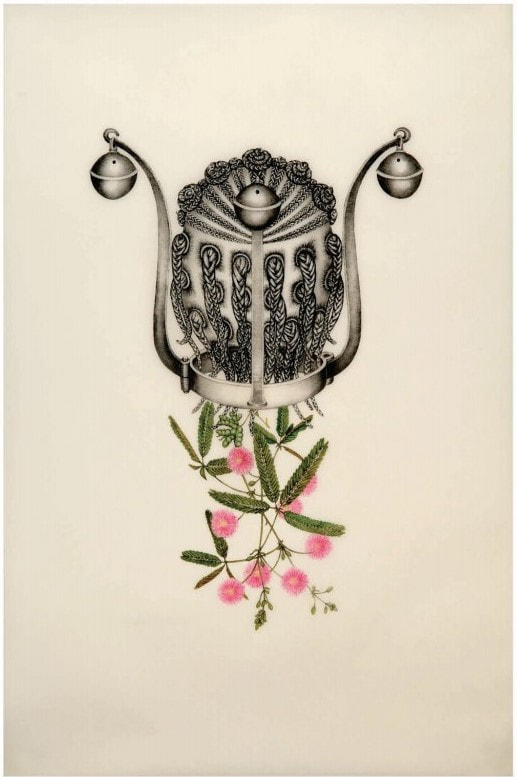

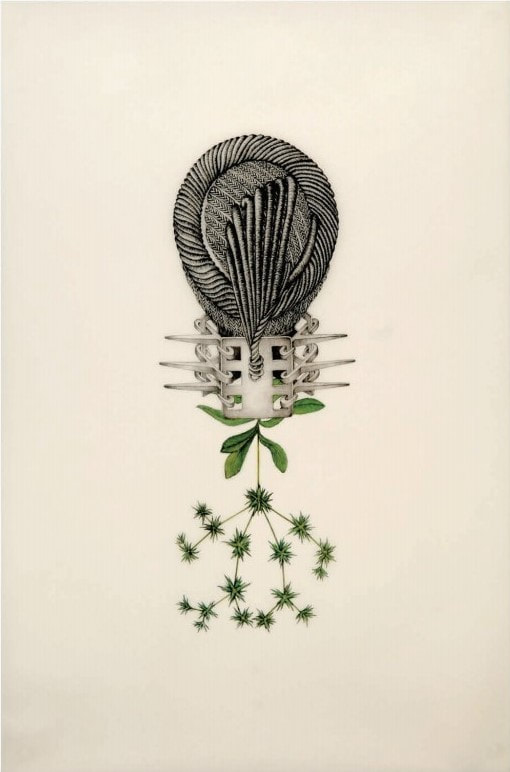

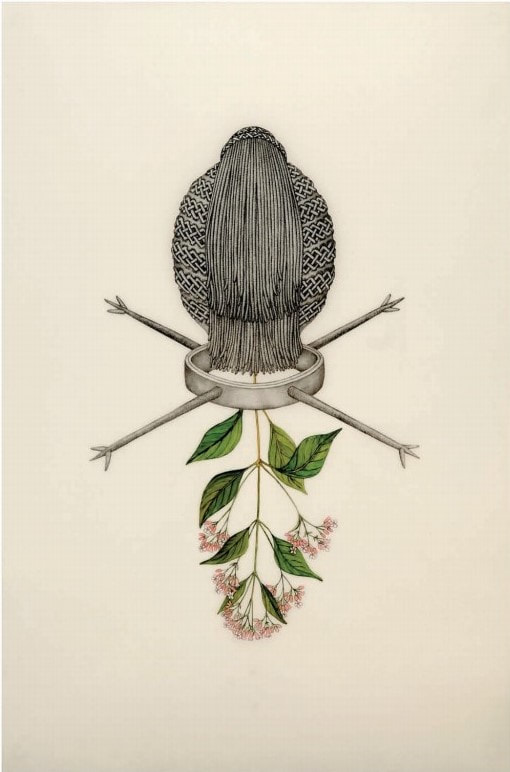

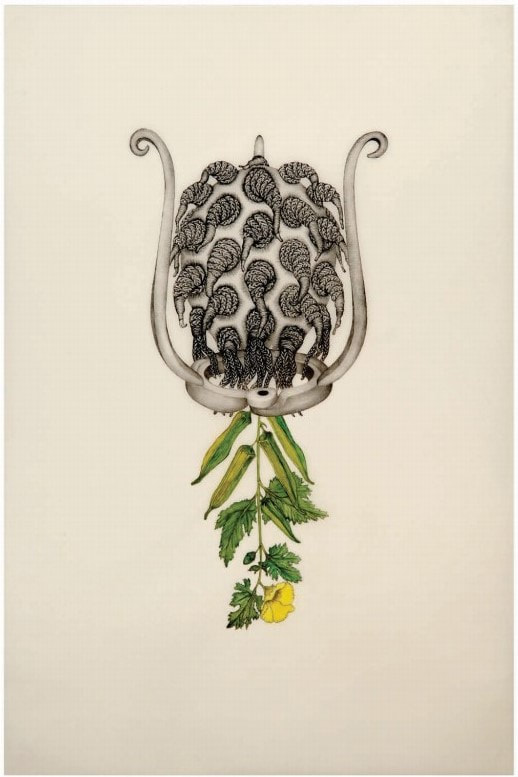

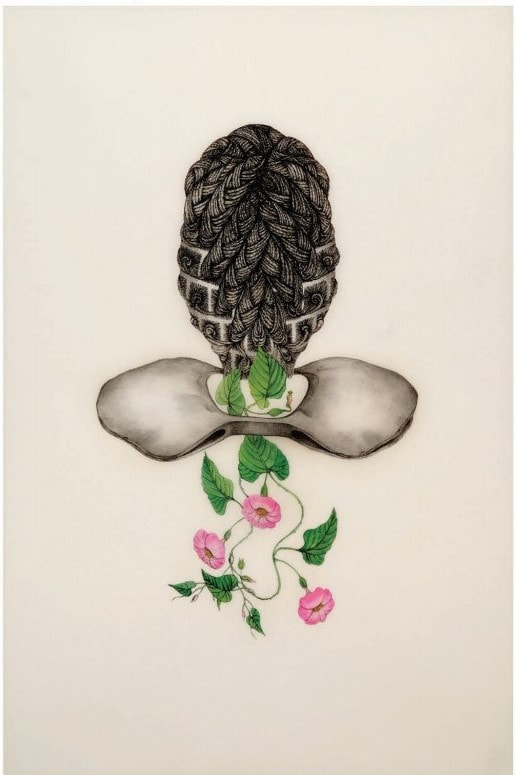

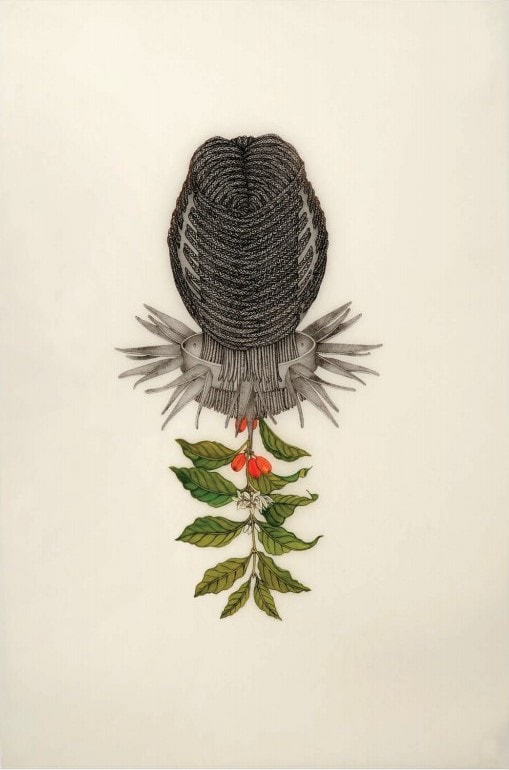

On a recent, long drive, we started listening to Isabel Wilkerson’s new book, Caste. The recording is fourteen hours long, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. In fact, we’re still in the eight-pillars-of-the-caste-system part that sets up the whole thing. It’s dense, intense, and important. One of the pillars was an ah-ha for me. It has to do with heredity, the idea that one’s caste is inherited through family. In most cultures, this placement into a certain level of society follows the patriarchal line. In America, however, from its earliest days, caste was passed down through the matriarchal line. This turnabout was necessary because it enabled the upper caste (white men/slave owners) to rape enslaved women in order to produce yet more slaves that could add to the labor force or be sold for a profit. Rape as a profit center. It makes me sick. Maybe I’m naïve for being surprised, but that one really got to me. WTAF?!? After the trip, a friend/colleague mentioned the artist Joscelyn Gardner's portfolio, Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers…, 2009–11, and I knew it would make a powerful post. It also felt like no coincidence that she told me about the works at the same time I’m deep in Wilkerson’s book. I have never resisted talking about and introducing you to works that pack a political punch. Hold on to your hats, here we go. First, know that Gardner’s portfolio intertwines information gleaned from the papers of an English slaveholder and amateur botanist named Thomas Thistlewood who settled in Jamaica in 1750. His papers are well known and are one of the fullest and most extensive accountings of that period, including everyday matters having to do with the slave business, the weather, horticulture and botany, crops, and financial issues (they are held by Yale’s Beinecke Library). In addition, the papers include a meticulous accounting of his violent sexual transactions. Scholar Alison Donnell (in an exhibition catalogue featuring Gardner’s work from 2012) uses the term transaction because Thistlewood recorded in excruciating detail some 3,852 acts of intercourse with 138 women. He was no sex addict. Donnell goes on to pose these pertinent questions: “How do we represent the violence and violation of slavery without repeating its spectacular effect? How do we speak about subjects lost to history and yet not entirely unknown? How can we make visible the systems of representation that support an unequal distribution of authority, knowledge, and power?” Enter the artist Joscelyn Gardner. She grew up in Barbados where her family dates back to the seventeenth century—one can only assume they were land- and slaveowners—and now calls London, Ontario, home. In her portfolio of twelve lithographs printed on frosted Mylar (lending a particular luminescence), each portrait includes the head of an African woman seen from behind showcasing an elaborately braided hairstyle, a complicated torture device, and a delicate botanical specimen. The delicacy and intricacy of the rendering draws viewers in; it is an oft-used trope that usually works. In traditional portraiture, the subject faces the viewer, often confronting them. Portraits were created to showcase the sitter’s stature, knowledge, and wealth. Yes, these would be mostly men. Women were often portrayed as allegorical figures (nude, naturally), or in relation to the men in their lives. Gardner’s subjects have their backs turned to us, preventing us from knowing who they are individually. This does several things. It not only subverts the male gaze and objectification, but also allows the artist to portray women whose identities are lost to history. For me, they become symbols of the strength and determination of enslaved women without the spectacle of their circumstances. This seems especially appropriate in this instance because the artist herself is white. (This is a much larger debate that requires its own post.) In Gardner’s hands, the hair is the manner of capturing character as she bears witness to lives lived. The elaborate hairstyles of meticulous braiding mark each as an individual, but also reflect the sisterhood required to accomplish them. These hairstyles are based on contemporary examples tying the past to the present and acknowledging hair’s position as a signifier of personhood, status, and position, as well as being a key means of individual expression. But remember, hair is also a fundamental means of differentiating race and class. During slavery, the worn instruments of torture were visible manifestations of control and systematic enforcement of authority. Interestingly, depictions of bucolic plantation life appear in contemporaneous artworks, but few examples exist showing the habitual violence necessary for keeping the system operational. More truthful imagery begins to surface with the Abolitionist movement at the end of the eighteenth century, but the subjects are faceless—a continued effort to dehumanize slaves. This is surprising when one considers the power of postcards of lynchings produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that were widely shared and had the effect of reinforcing that terror. Perhaps the pastoral images of exotic plantations for a European audience naturalized the injustices that were codified into laws making men and women the property of others. By subverting accepted narratives of the era, Gardner recognizes slave women, gives them a voice and a presence. Representation matters. As the world became fascinated with classification of things, the definitions of words, the knowledge of how things worked, of Enlightenment, was this all code for “we have to justify the subjugation of ‘other’ human beings in order to build a new world?” The botanical specimens Gardner adds to each portrait echo the style of eighteenth-century books cataloging plants with exquisitely delicate illustrations. Gardner includes their Latin names—a colonizing effect wholly tied to European conventions of the study of natural history, which was a booming industry in the print trade in the eighteenth century. The names set in parentheses are not the common names of the plants but the names of slaves from Thistlewood’s diaries, reflecting another colonizing act in which the assignment of names was arbitrary and separated slaves from their African identities—more subjugation and dehumanization. But the applied knowledge of plants has long been the domain of women, and whose use has long been distrusted by men. Remember healers were thought to be witches in the early years of the Republic? In Gardener’s prints, these particular plants are in fact Abortifacients, which were used to abort unwanted pregnancies. Gardner’s portraits allow these women to control the male gaze upon them, display individualism through hairstyles, acknowledge but transform the objects of torture, and twist Thistlewood’s intense interest in botany to identify plants used to counter his attempts to impregnate and profit from the births of black bodies carried by women with few options. Notes: The portfolio was printed at Open Studio, Toronto, with master lithographer Jill Graham. See the thorough and thoughtful catalogue on Gardner’s work that includes essays by Jennifer Law, Alison Donnell, and Janice Cheddie here: https://fcd17b62-2ec4-4ce5-8701-cf90a26cd17a.filesusr.com/…. Joscelyn Gardner (Barbadian and Canadian, born 1961) Printed by Jill Graham, Open Studio, Toronto Aristolochia bilobala (Nimine), 2010 Bromeliad penguin (Abba), 2011 Trichilia trifoliate (Quamina), 2011 Veronica frutescens (Mazerine), 2009 Mimosa pudica (Yabba), 2009 Eryngium foetidum (Prue), 2009 Cinchona pubescens (Nago Hanah), 2011 Hibiscus esculentus (Sibyl), 2009 Manihot flabellifolia (Old Catalina), 2011 Convovulus jalapa (Yara), 2010 Petiveria aliacea (Mirtilla), 2011 Coffee arabica (Clarissa), 2011 From the portfolio Creole Portraits III: bringing down the flowers… Portfolio of twelve lithographs with hand coloring on frosted Mylar Each sheet: 915 x 610 mm (36 x 24 in.)

0 Comments

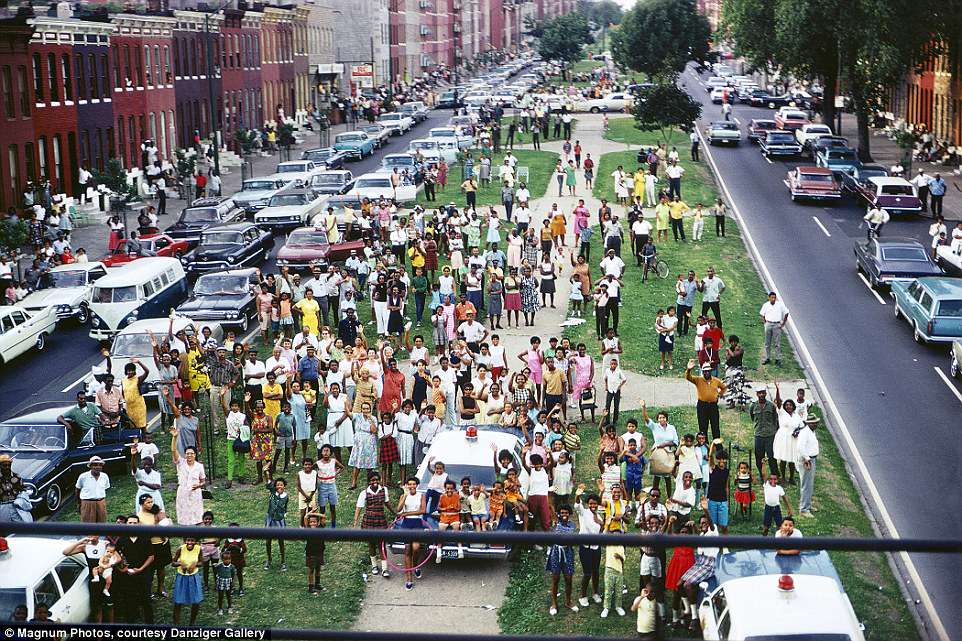

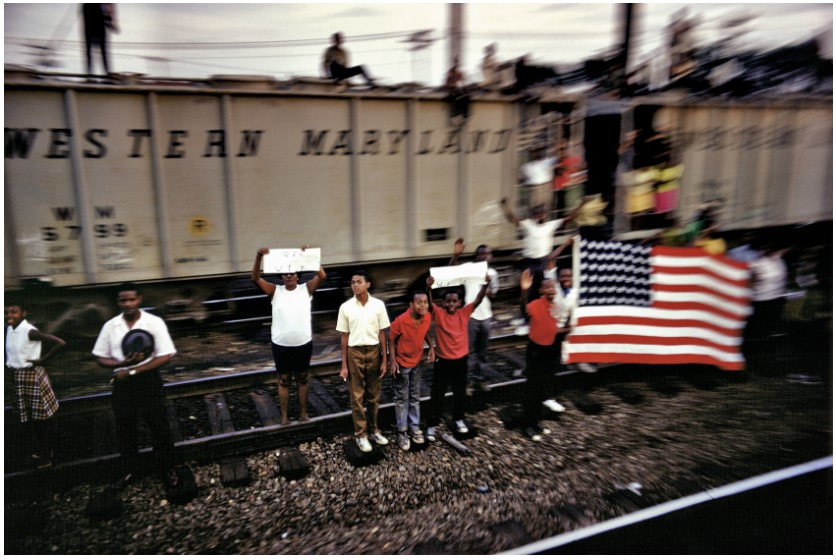

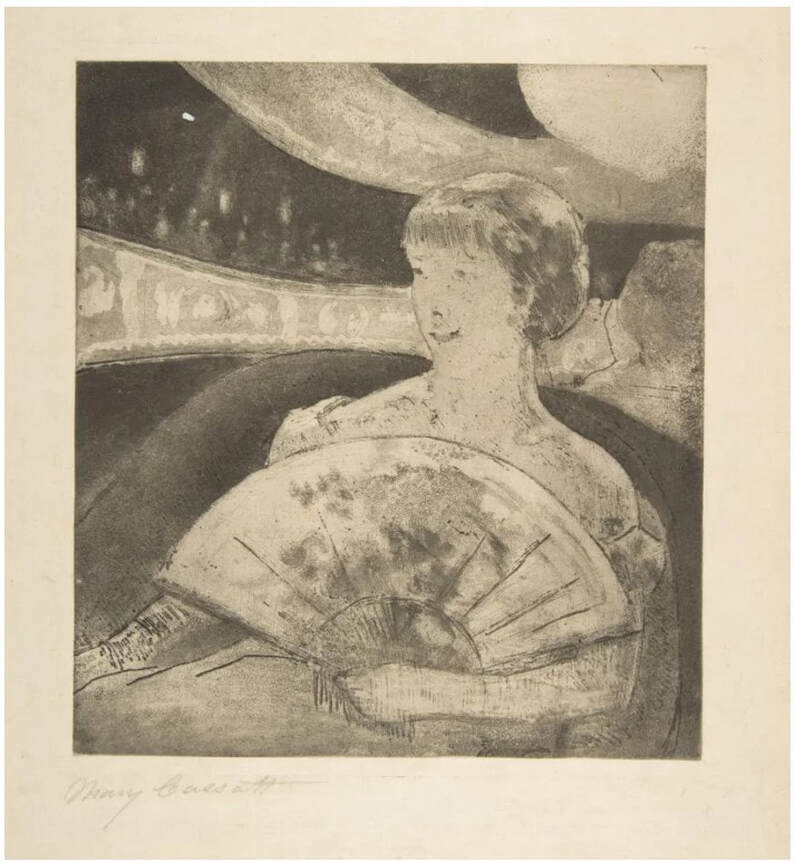

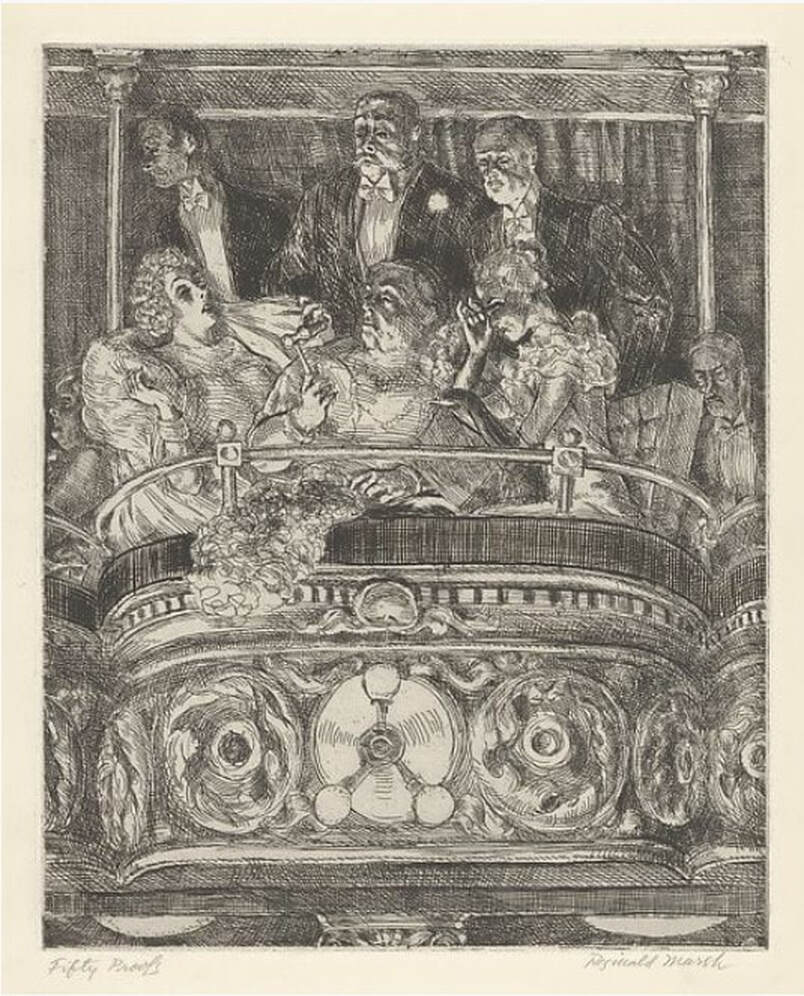

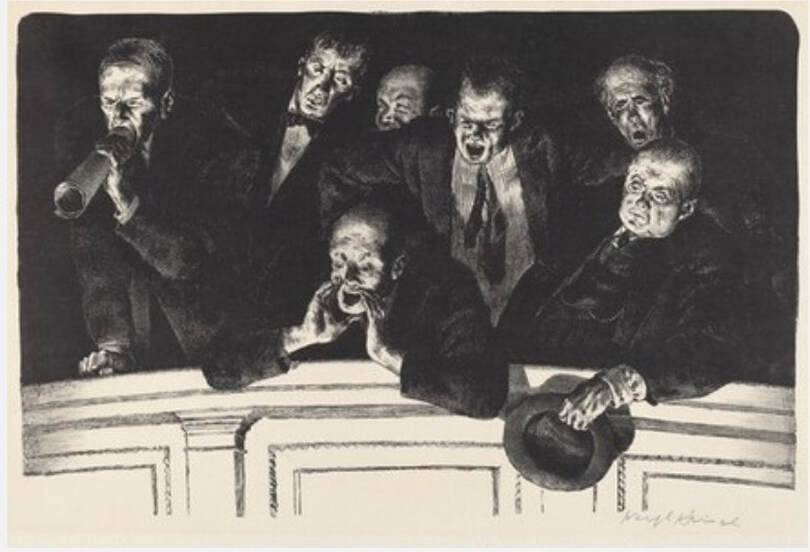

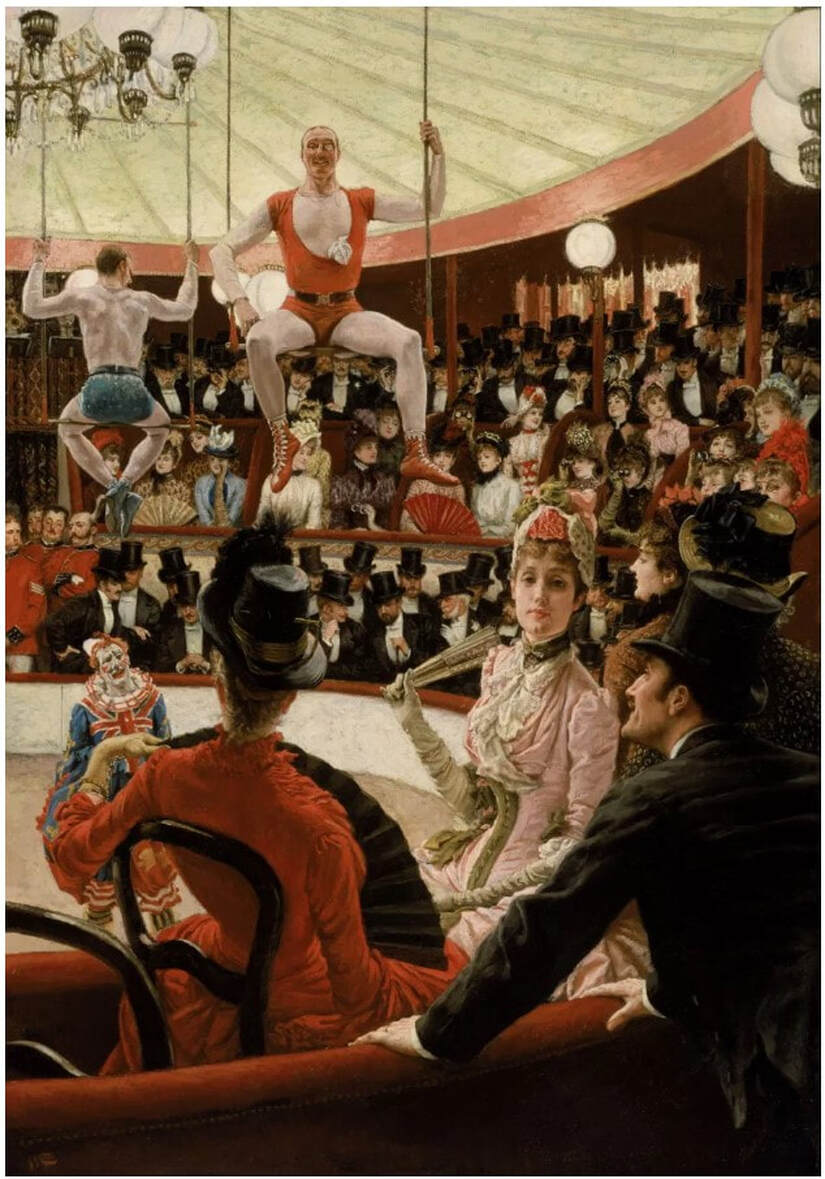

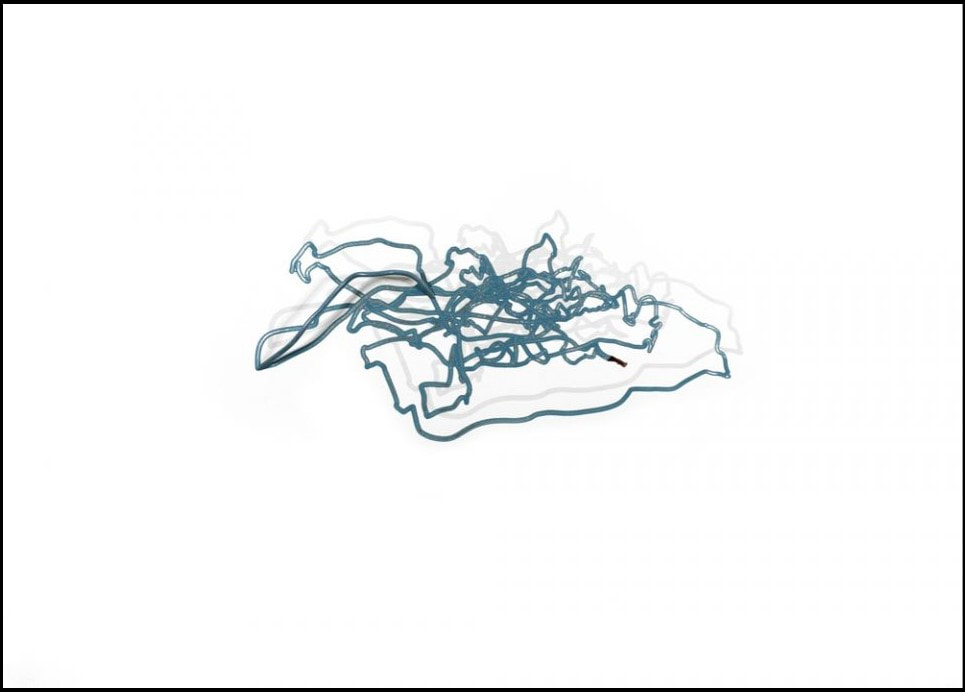

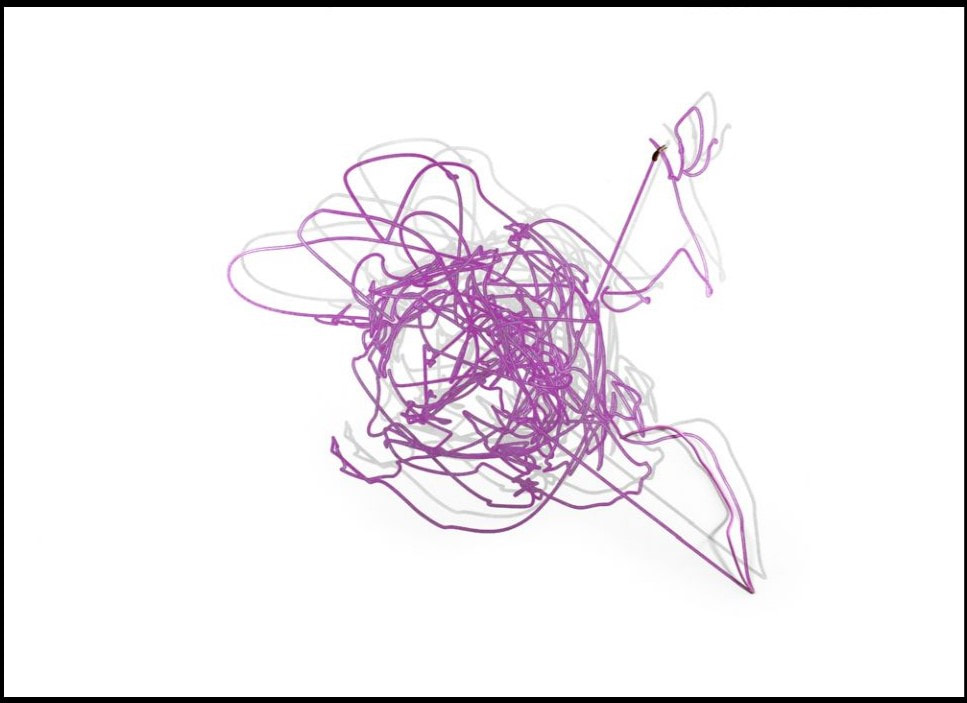

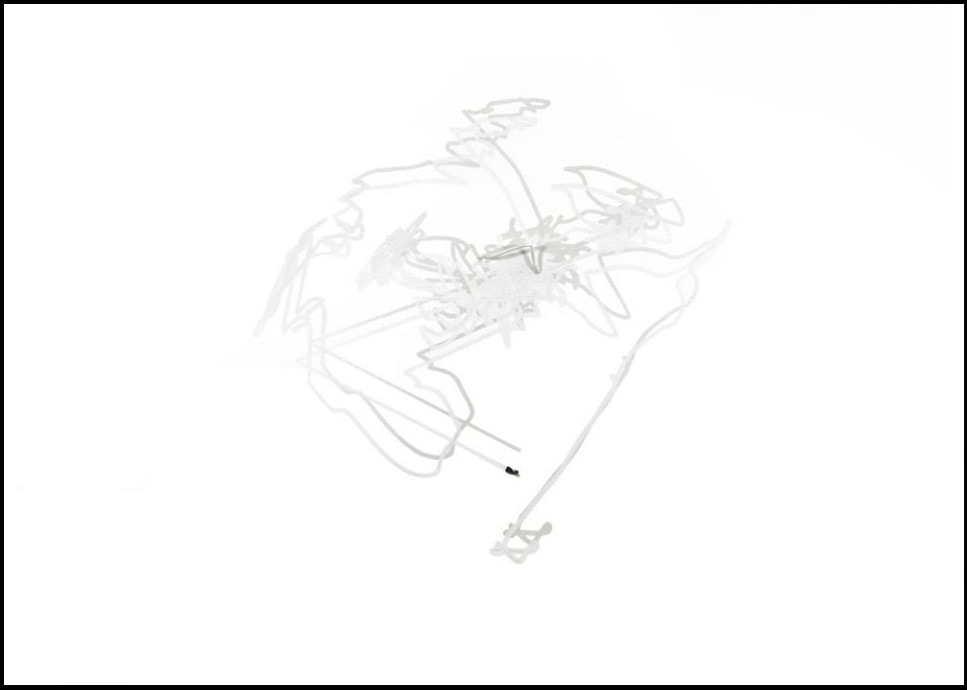

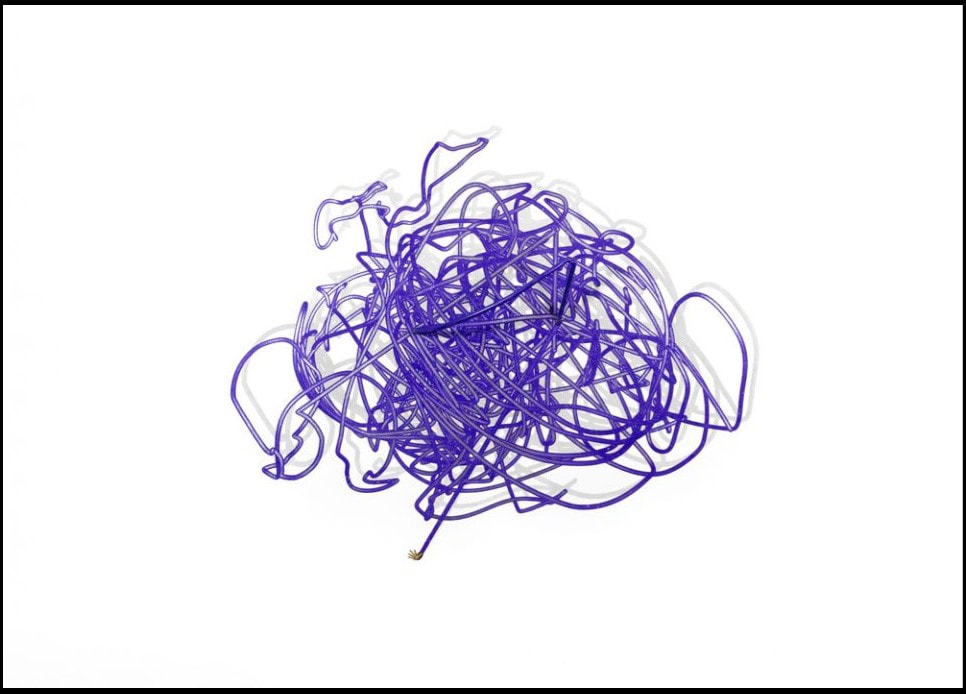

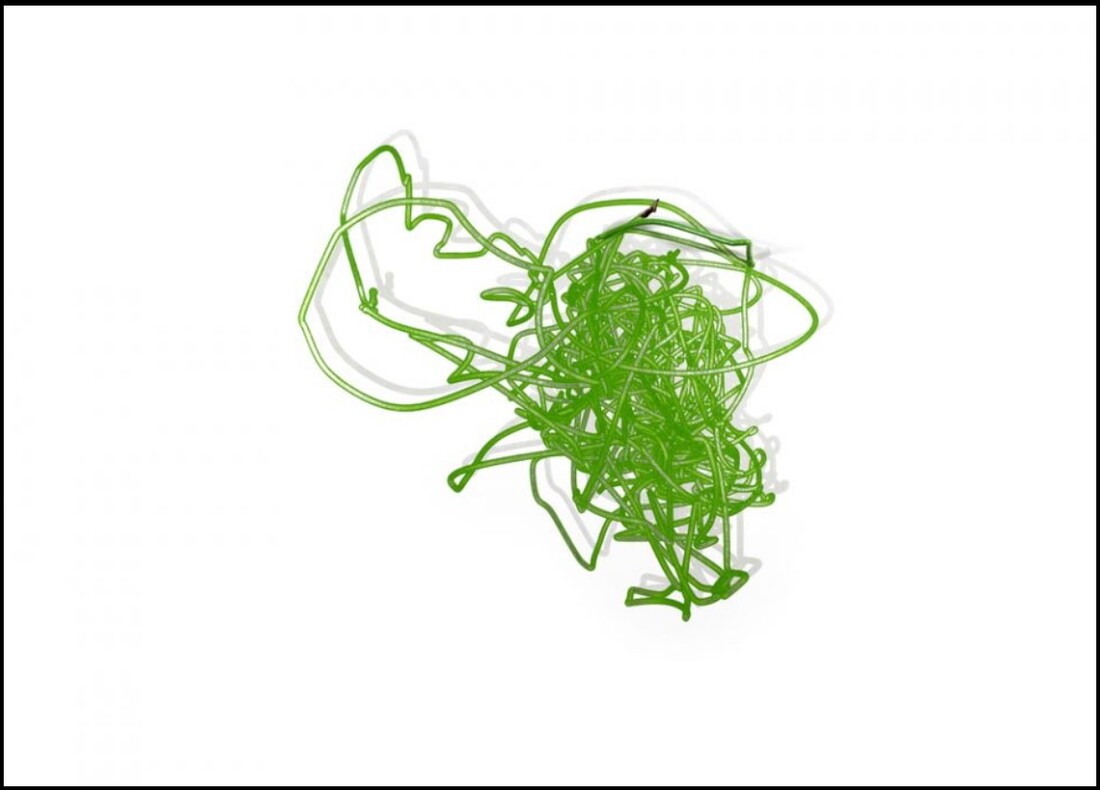

Ann ShaferI always wanted to do an exhibition about the audience. Portraying not the main attraction—the action on stage—but the people who are watching seems ripe for capturing a slice of life. The lookers being looked at flips convention. Voyeurism is a funny thing, alternately creepy and, what’s the opposite of creepy? Oh, pleasant. There are some great prints from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that would fit in this proposed exhibition nicely like Mary Cassatt’s In the Opera Box, 1879, Reginald Marsh’s Box at the Metropolitan, 1934, Joseph Hirsch’s Hecklers, 1943. Of course, there are plenty of paintings portraying audiences, too. My favorite is Tissot’s Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885. Though these images may seem quirky and quaint now, it is possible for an image of this type to cross over into social justice and to capture the zeitgeist. For me, one of the most searing group of images of an audience is Paul Fusco’s series taken in 1968 from the train carrying the body of Robert F. Kennedy from New York to Washington, D.C., for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The photographs capture an emotionally naked populace witnessing the end of optimism in the country. RFK’s assassination followed that of his brother, President Kennedy on November 22, 1963; Malcolm X on February 21, 1965; and Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968. RFK was shot just two months after Dr. King’s death, on June 5, 1968. By then, the country had seen more than its share of sorrow and senseless killing. The photographer, Paul Fusco, died last week, and it reminded me of how powerful the images are still. I marvel at how much emotion is conveyed across decades; they give me chills to this day. It may not surprise you to know that one of the photographs, a shot up North Broadway, just before the train dips underground on its approach into Penn Station in Baltimore, is one that got away. I pitched this photograph some years ago and got enough pushback to return it to the dealer. Part of the issue was that my colleagues weren’t convinced it was Baltimore in the photograph (of course it is), and the other had to do with vintage prints versus later reprints. Many curators seek and prefer to collect vintage prints, meaning the photographs were printed at the time they were shot. The photograph in question was a later printing, and thus was less desirable. I am certain Fusco wasn’t thinking in terms of museum collections in 1968. In fact, as a member of Magnum Photos, an international cooperative agency, he was on assignment for Look magazine, which published two of the photographs in black and white. The series was unknown until Aperture published it in 2008. Hence the later printings. In an earlier post I said I have never forgotten those that got away, and it’s true. To this day, when I see one of these works on the wall in some exhibition, I think “yes, I was right.” A few years after my failed pitch, I saw an exhibition of Fusco’s RFK train pictures at SFMoMA, and there was the North Broadway shot, front and center. Vindication. Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (North Broadway, Baltimore), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Family), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Western Maryland Railroad), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926) In the Opera Box (No. 3), c. 1880 Etching, softground etching, and aquatint Sheet: 357 x 269 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 9/16 in.) Plate: 197 x 178 mm. (7 3/4 x 7 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Imrie de Vegh, 1949, 49.127.1 Reginald Marsh American (1898–1954) Box at the Metropolitan, 1934 Etching and engraving Sheet: 250 x 202 mm. (9 13/16 x 7 15/16 in.) Plate 322 x 252 mm. (12 11/16 x 9 15/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of The Honorable William Benton, 1959, 59.609.15 Joseph Hirsch (American, 1910–1981) The Hecklers, 1943–1944, published 1948 Lithograph Sheet 312 421 mm. (12 5/16 x 16 9/16 in.) Image: 251 x 388 mm. (9 7/8 x 15 ¼ in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2503 James Tissot (1836–1902) Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885 Oil on canvas 147.3 x 101.6 cm. (58 x 40 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 58.45 Ann ShaferHere’s another one that got away. And at my very last opportunity before leaving the museum, too. Rashaad Newsome’s 2016 set of lithographs were front and center in Tamarind’s booth at the 2017 Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. The five lithographs are part of a larger project that begins with a performance of five dancers voguing, which was captured by an Xbox Kinect the artist reprogrammed. Five classic voguing dance forms were performed. The energetic swirls of their movements were captured digitally and subsequently translated into both sculptures and prints. Check out this video of Tornado Revlon. In the performance, each dancer—all of whom are well known in the voguing world—performs a different move: a catwalk is performed by Star Revlon; rapid hand movements are performed by Tornado Revlon; duck walking is performed by Justin Monster Labeija; spin dips are performed by Davon Amazon; and floor work is performed by Jamel Prodigy. For the Tamarind lithographs, the digitally tracked movements are printed in different colors, and a tiny plastic body part that indicates which part was tracked is collaged onto each print. They are 29 ¾ x 42 inches each. I knew they would both have wall power and draw people in. Newsome’s work looks at agency and privilege, asking who gets it, when, and why. Vogue balls, events that became widely known through the 1990 film Paris is Burning, is currently the subject of an FX series called Pose, which is streaming on Netflix, Amazon Prime, and elsewhere. I imagine that people in the voguing world have mixed feelings about being put under a microscope and portrayed by actors, particularly since vogue balls have always been recognized as safe spaces for Black and queer people. But that moniker “safe space” implies outsiders aren’t welcome. What do you do when Hollywood comes calling? Newsome’s performance regains agency for the performers themselves (Newsome is a part of the community) and brings it to the fine art world. Just as balls are safe spaces, I would postulate that artmaking is a safe space, too. In their need to investigate themes, problems, and ideas deeply, artists must have their own safe spaces where ideas are put through the conceptual sausage grinder and are transformed into something that starts conversations and spurs thinking and feeling. I like the parallels. You may recall I love the idea of taking dance/movement to the walls of a gallery (see my post about Trisha Brown). Works that cross disciplines have always interested me. But also because performance art is difficult to collect because of its ephemerality, I appreciate creative ways of capturing it. Just as Stan Shellabarger’s walking book (see earlier post) was the product of its own creation, Newsome’s prints capture performance through digital tracking technology. I am not particularly interested in performance art through documentary photographs. Newsome’s tracked movements translated into a jumble of frenetic energy are more evocative of the performance than any photograph could ever be. I thought it would be a great fit for the collection. Truthfully, I can’t recall which straw man quashed the acquisition. While I got used to disappointments over the years, I can still conjure the feeling of frustration. I used to always say: “I should have been a collector.” Oh well, guess I’ll just keep writing about it. Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Five multi-color lithographs with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet (each): 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Catwalk (Star Revlon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Hands (Tornado Revlon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Duck Walking (Juston Monster Labeija), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Spin Dips (Davon Amazon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Floor Performance (Jamel Prodigy), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed