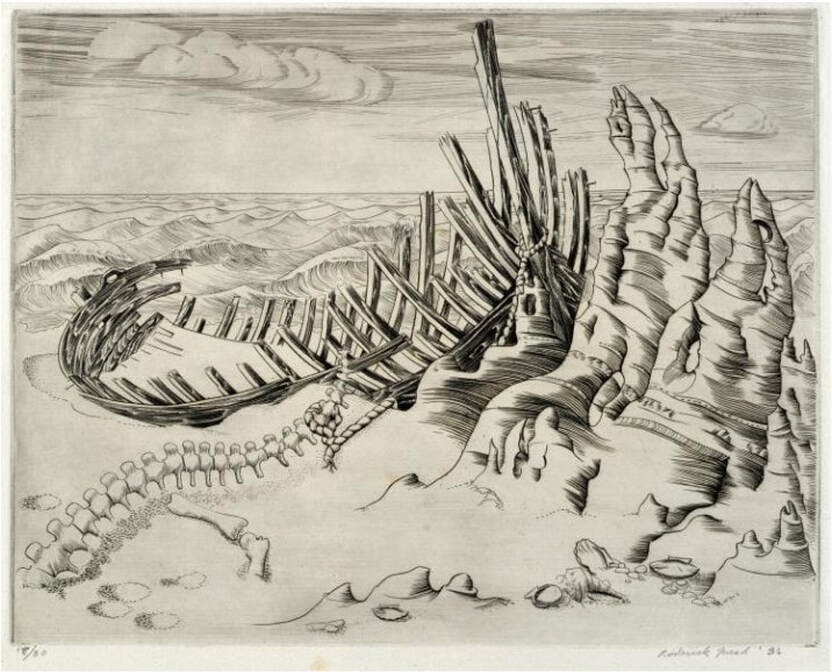

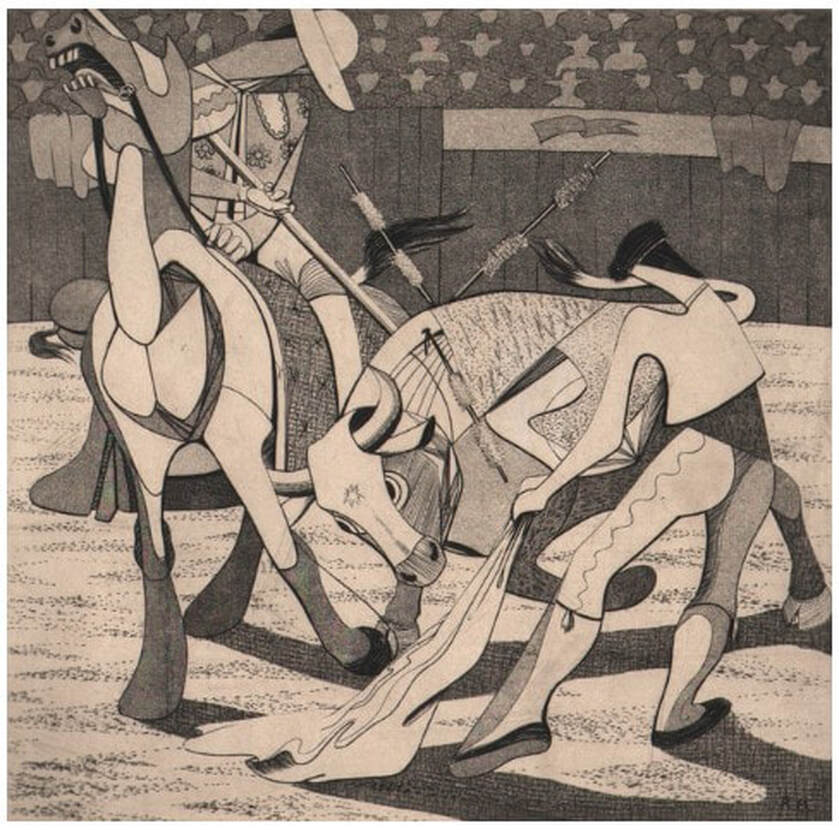

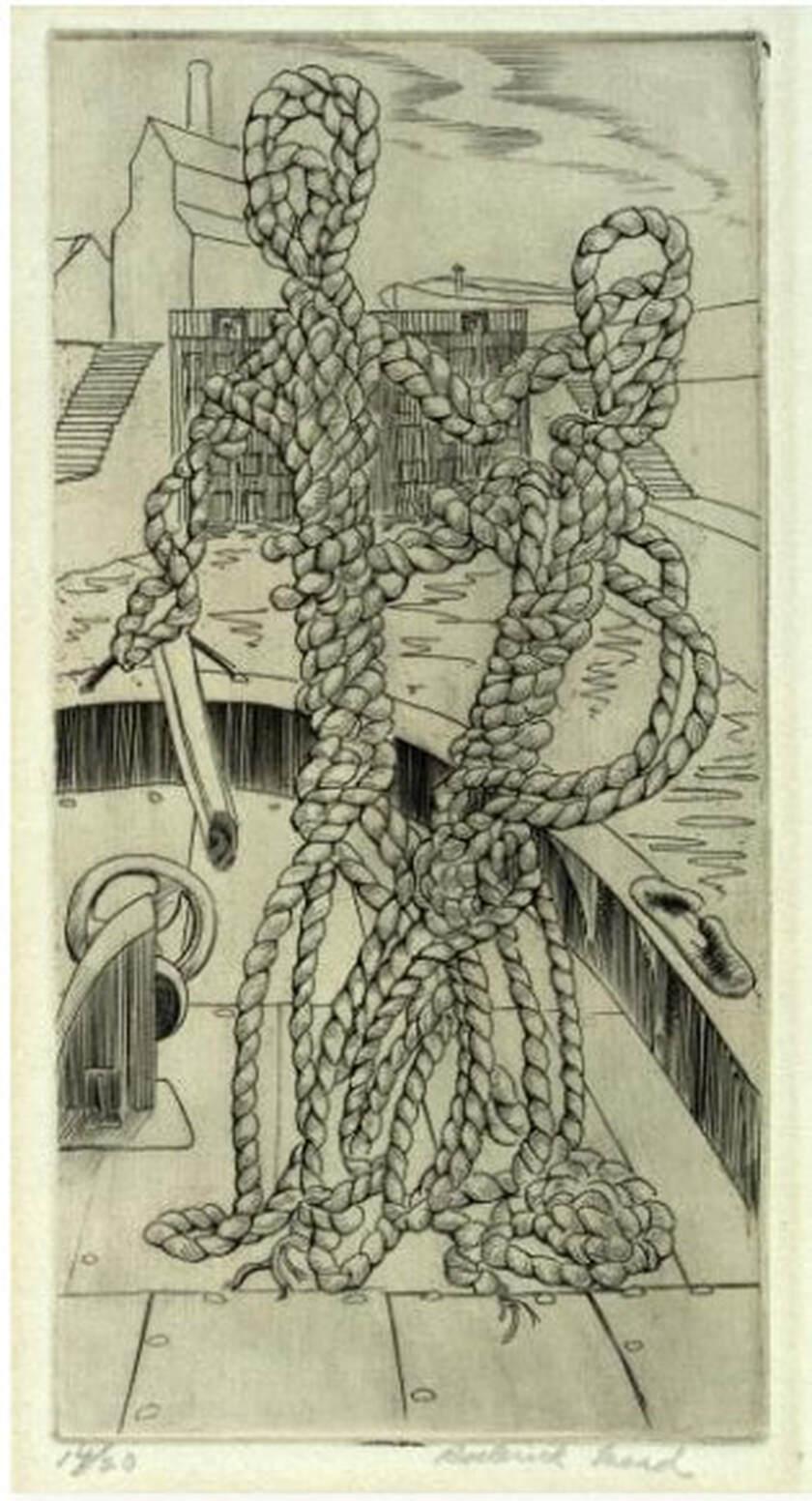

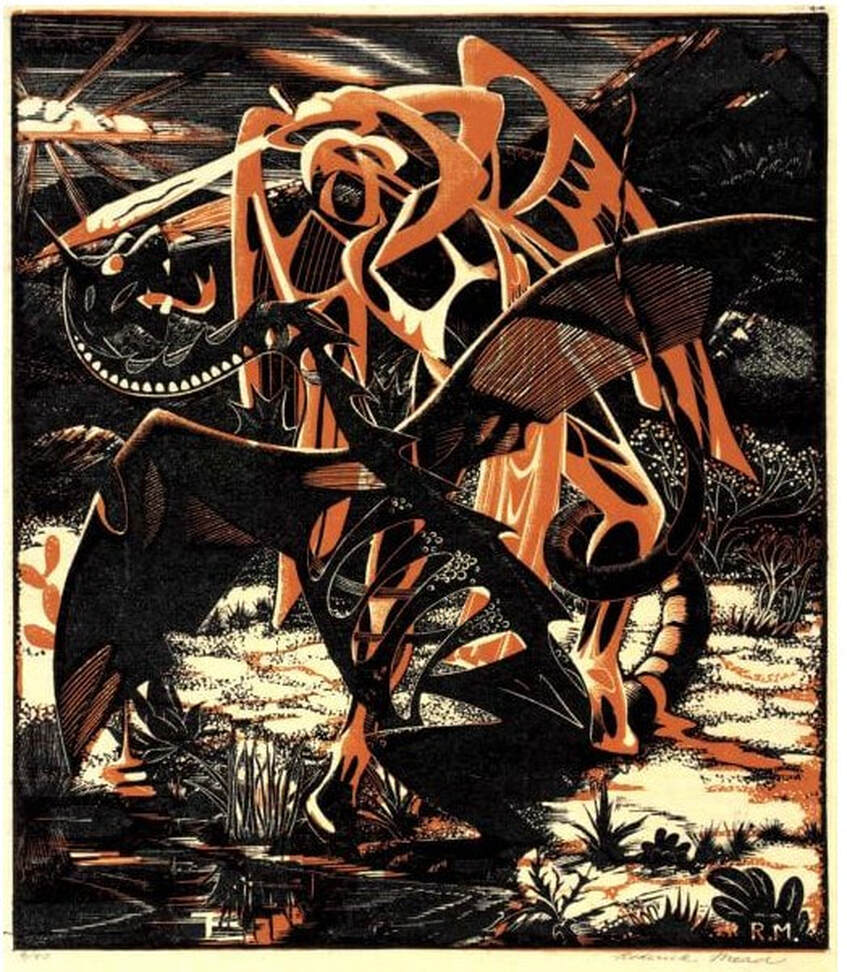

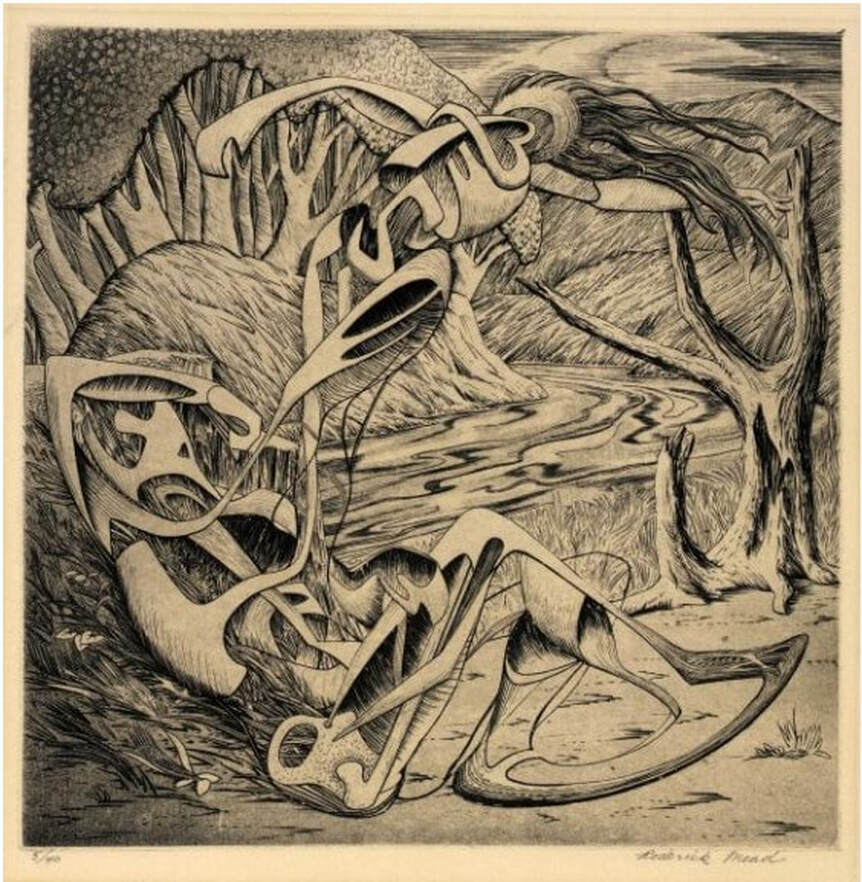

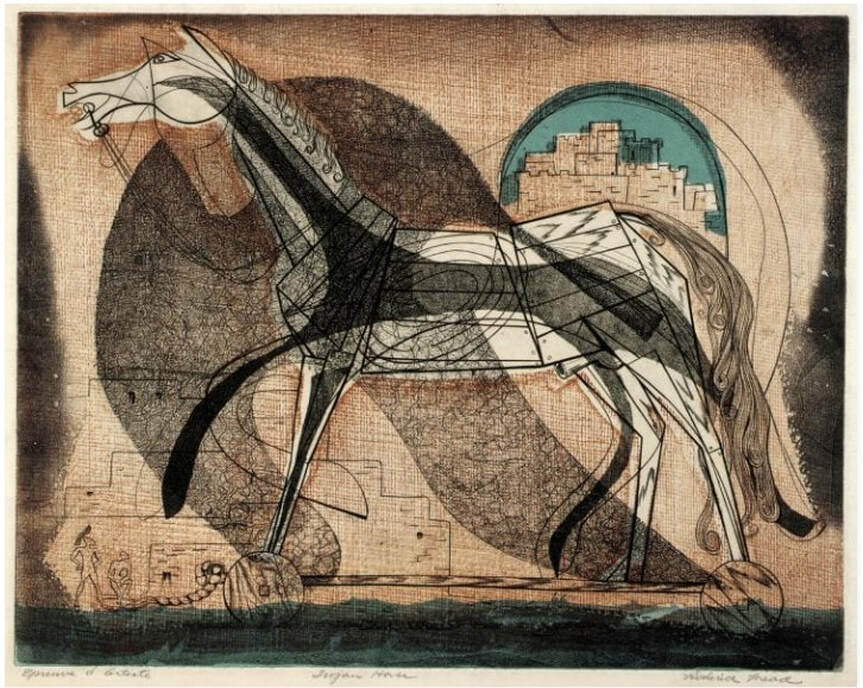

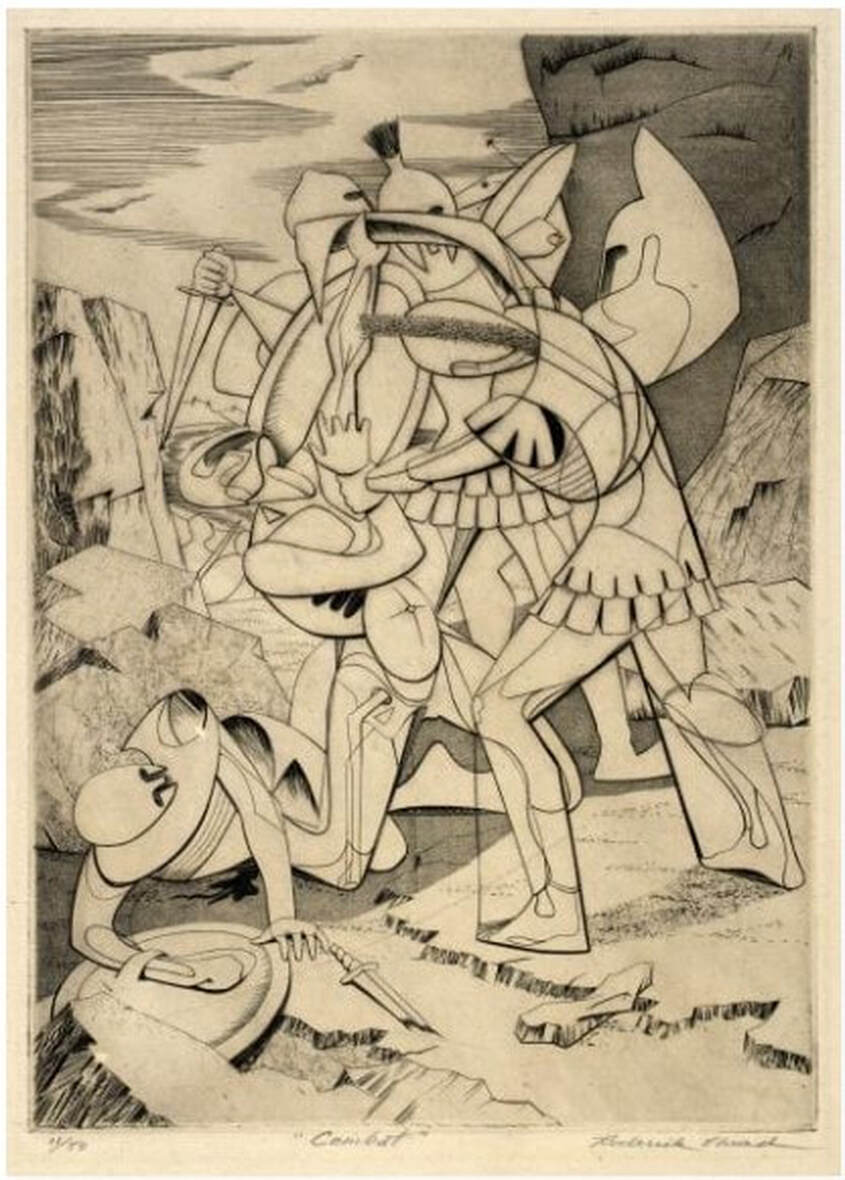

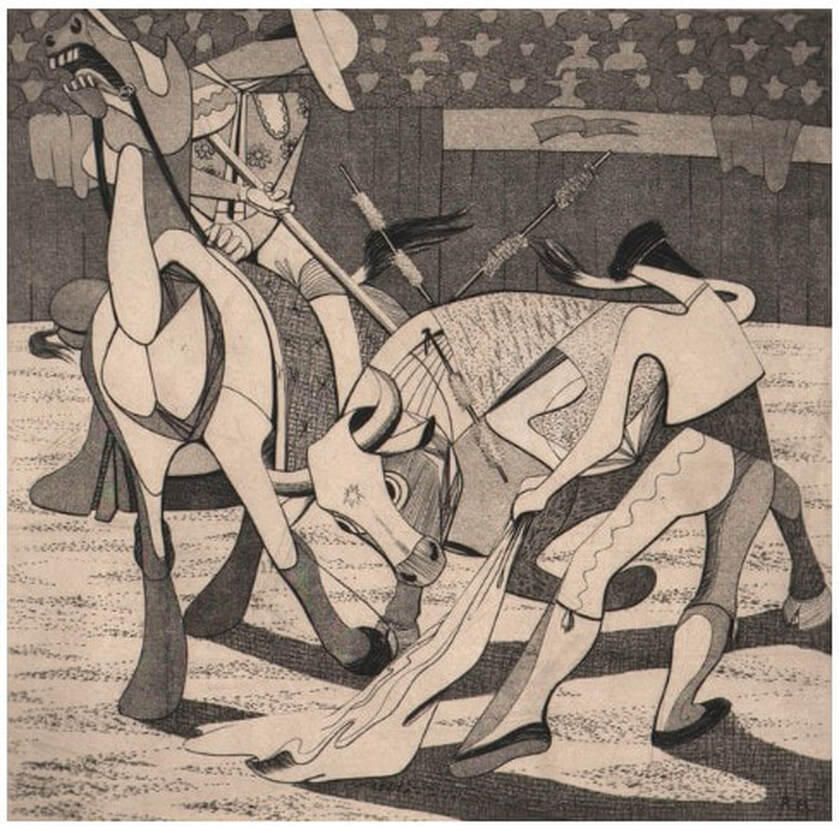

Ann ShaferLast week I posted a few images of praying mantes in prints. Fascinating creatures. By the terribly scientific polling apparatus available to me—number of likes, natch—I decided to post more images by the person whose praying mantis print was most admired, Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971). Mead grew up in New Jersey and attended Yale University, graduating in 1925. Following art school, he moved to New York where he studied at the Art Students’ League under George Luks (and later with him privately) for several years. He also studied watercolor painting with George Pearse Ennis at the Grand Central School of Art. In 1931, Mead moved to Majorca. Three years later he moved his studio to Paris and began studying printmaking at guess where? The experimental studio run by Stanley William Hayter known as Atelier 17. Actually, in 1931, the atelier was only a few years old and had yet to take up the name it would become known by. It wasn’t until 1933 that the studio moved to 17, rue Campagne Première, from which the 17 in its name derives. But you can be sure that Mead absorbed as much as he could there and as a result, the effect on his style is clear. At the Atelier on any given day one might be working at a table next to Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Jean Hélion, or Wassily Kandinsky. Like most of the artists there, Mead experimented with abstraction and surrealism, and one finds shared ideas, forms, and styles among the prints made there. Like most everyone else, Mead and his wife left Paris in 1939 ahead of the start of World War II and by 1941 was living in Carlsbad, New Mexico. There he was able to devote himself to creating art full time; he continued to paint and make prints until his death in 1971. For me, Mead would have been one in a long list of artists working with Hayter about whom I know not a great deal was it not for my friend Gregg Most, who grew up down the street from the Meads. Gregg and I worked together at the National Gallery in the 1990s, and he has researched and collected Mead for a long time. It is Gregg’s passion for Mead that caused me to pay closer attention. I love Mead’s prints because they are carefully crafted, readable yet totally surreal, and have a high sense of crispness and design that really attracts me. See if you agree. Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) The Wrecked Ship, 1936 Engraving Plate: 197 x 251 mm. (7 ¾ x 9 7/8 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.1 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) Untitled (Matador and Bull), c. 1936 Engraving and softground etching with aquatint Plate: 203 x 203 mm. (8 × 8 in.) Dolan/Maxwell Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) Rope Figures, c. 1935–45 Engraving Plate: 160 x 82 mm. (6 1⁄2 x 3 1⁄4 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1976.99.5 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) St. Michael and the Dragon, 1939 Color wood engraving Image: 232 x 203 mm. (9 1/8 x 8 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.6 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) Creation of Eve, c. 1942 Engraving and softground etching Plate: 200 x 199 mm. (7 7/8 x 7 13/16 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1976.99.1 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) Trojan Horse, c. 1945–50s Color engraving, aquatint, and softground etching Plate: 235 x 298 mm. (9 ¼ x 11 ¾ in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.2 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1971) Combat #1 (Incident), c. 1942–45 Engraving and softground etching 264 x 186 mm. (10 3/8 x 7 3/8 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.3 Roderick Mead, (American, 1900–1971) Tauromachia I, 1946 Engraving and aquatint Plate: 114 x 182 mm (4 ½ x 31/4 in.) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation, California State Library loan, L543.1966

1 Comment

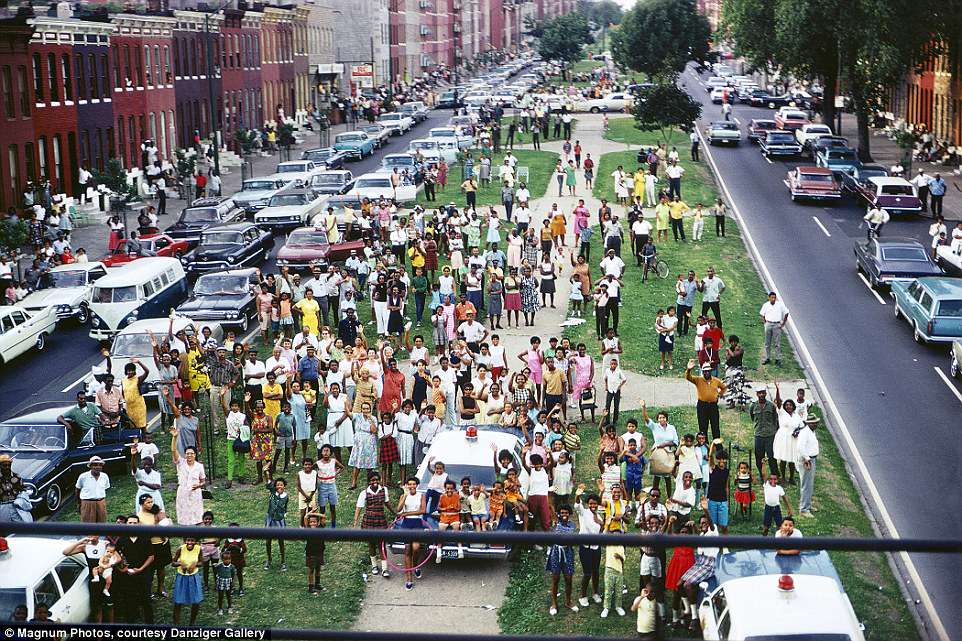

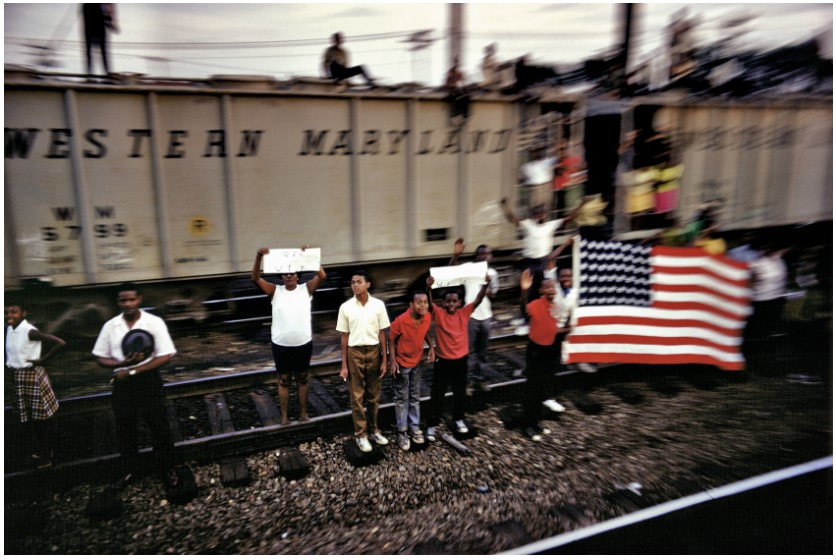

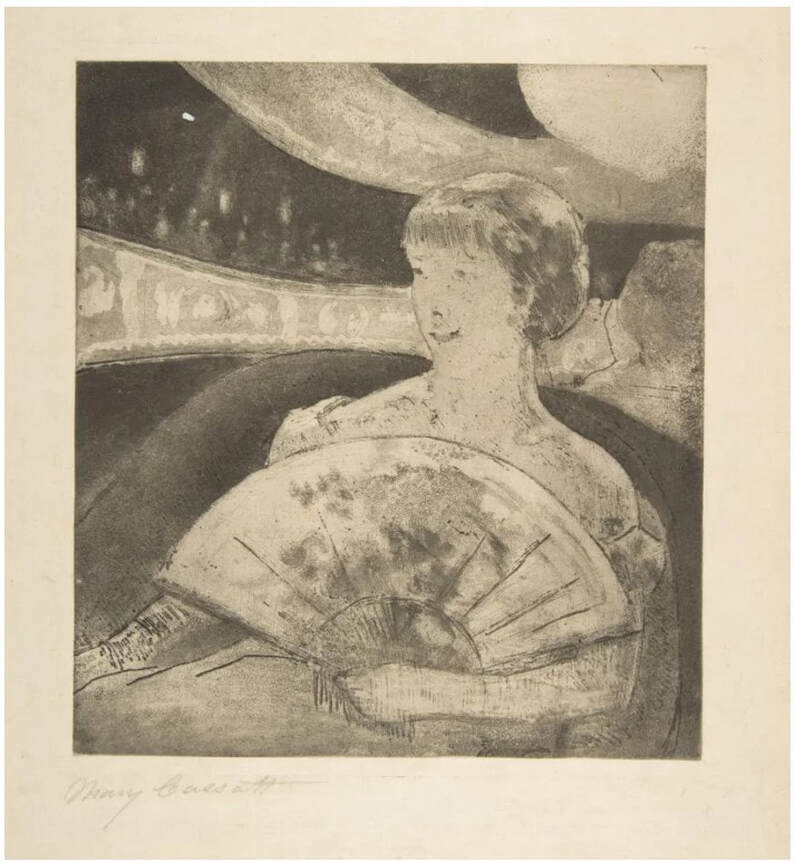

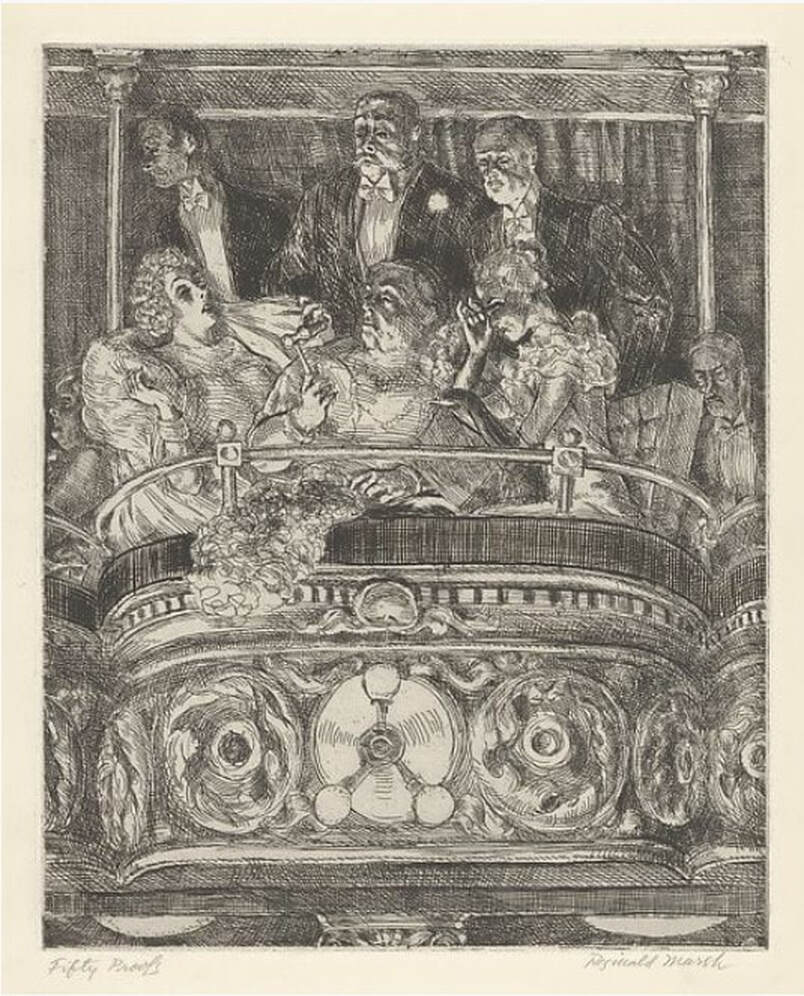

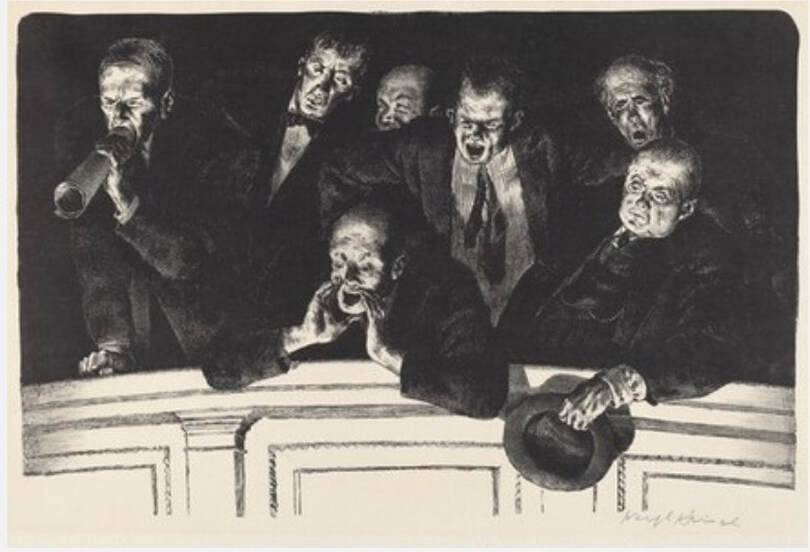

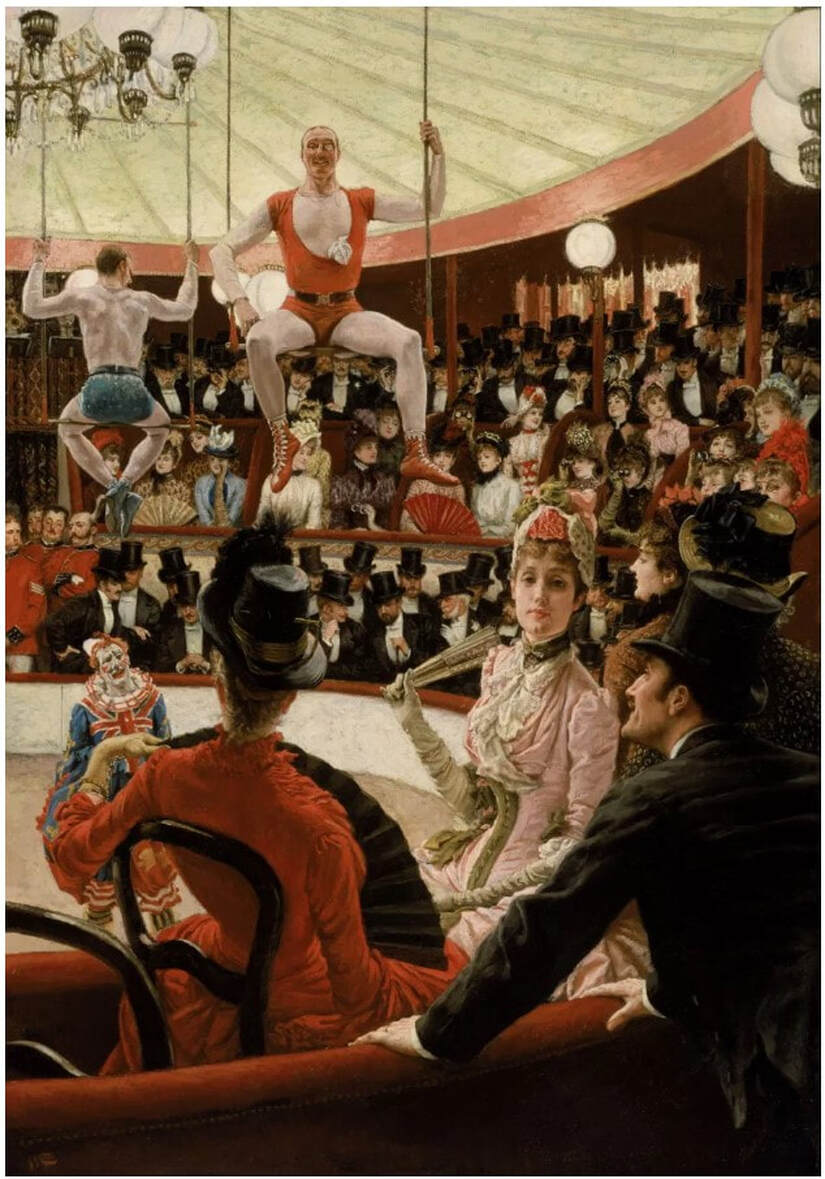

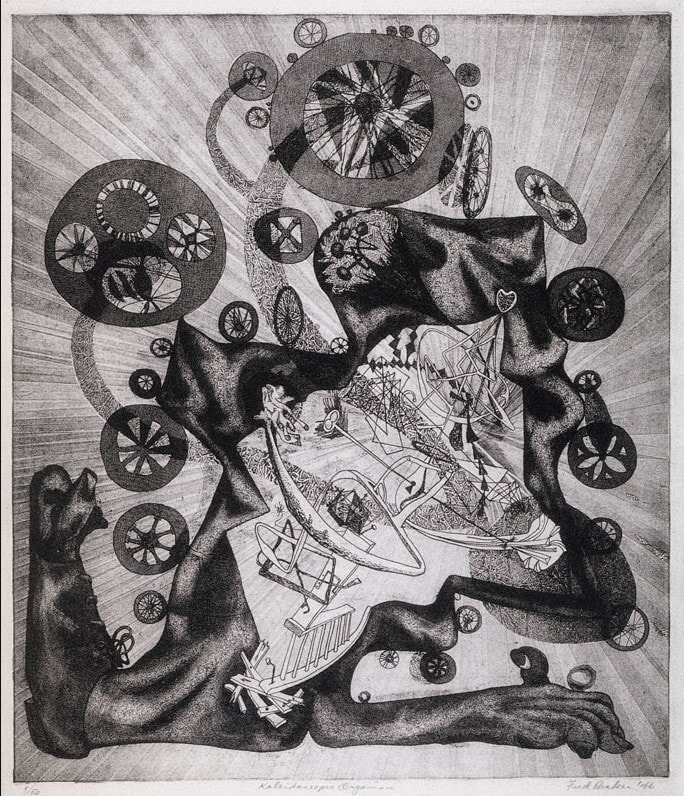

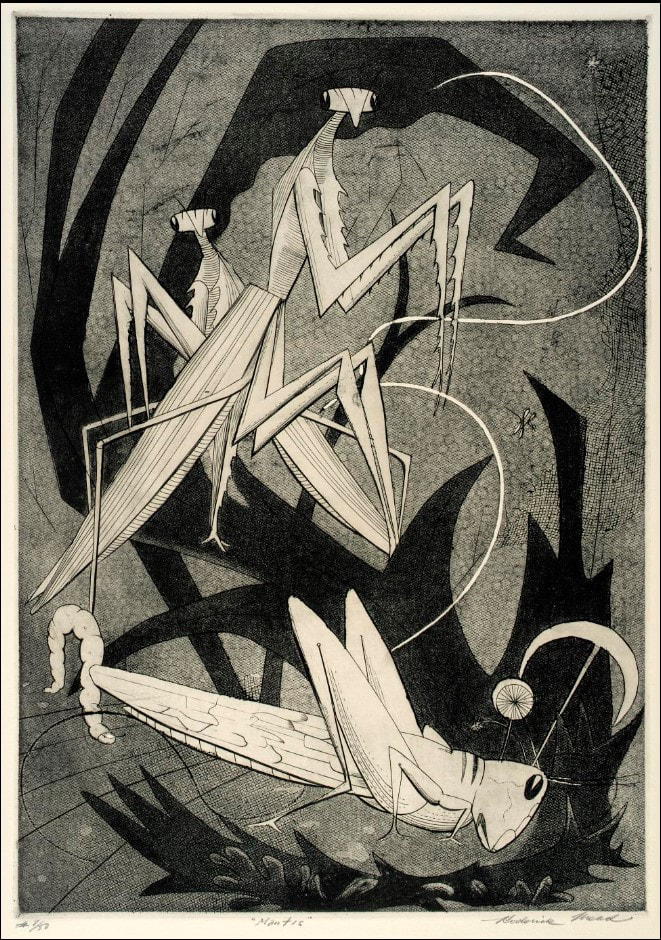

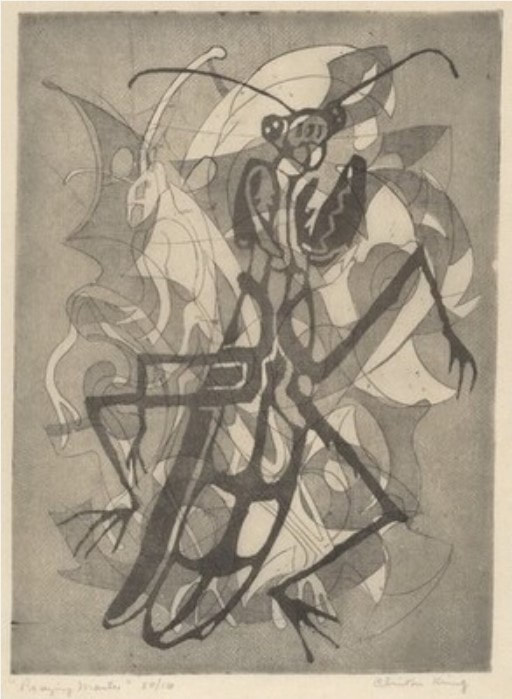

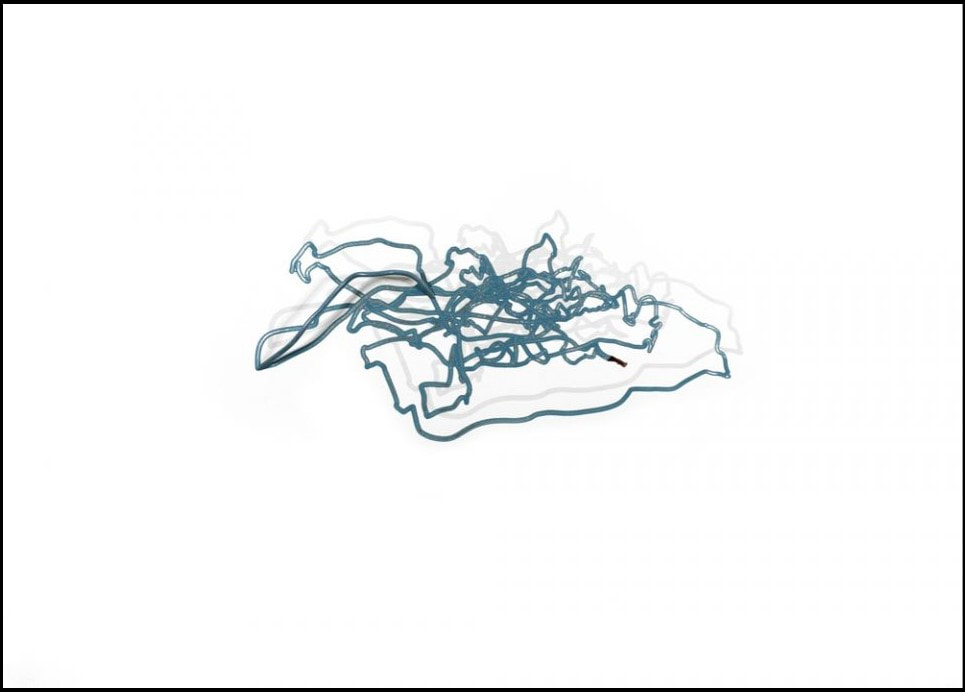

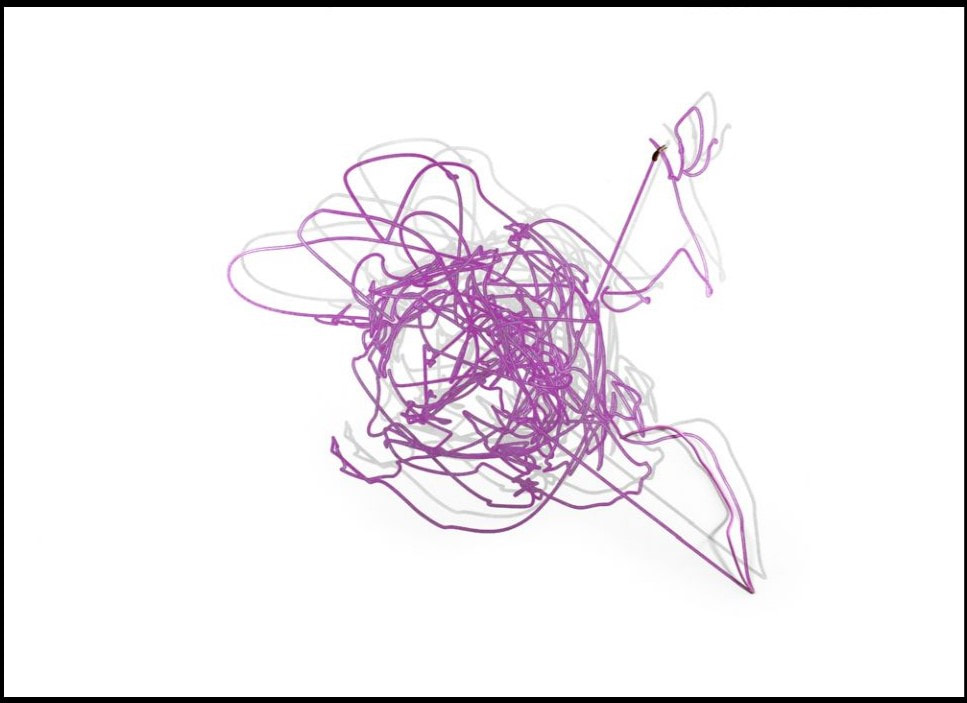

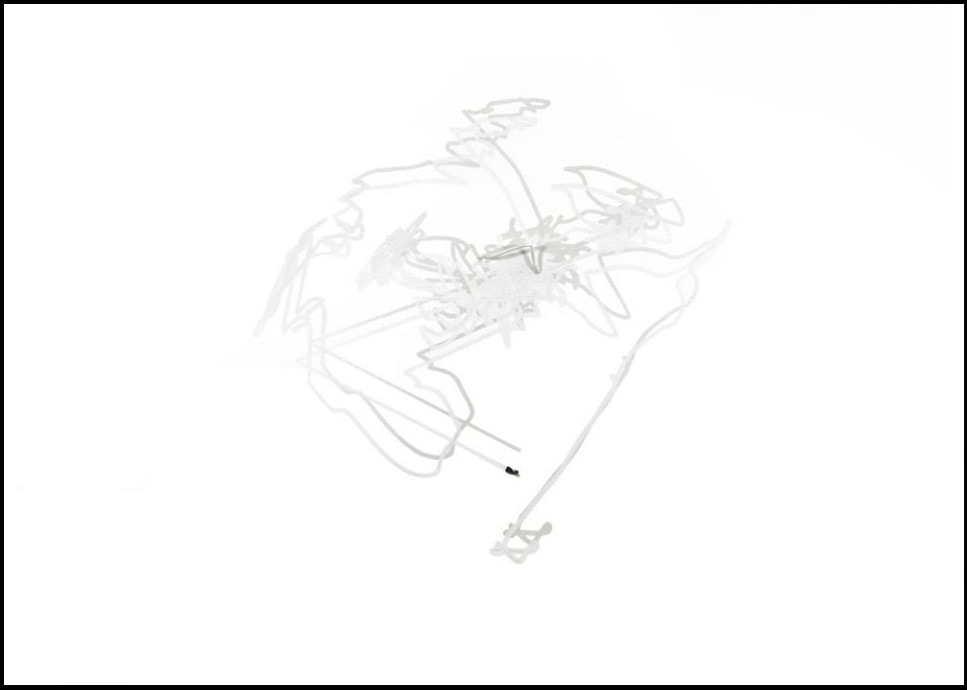

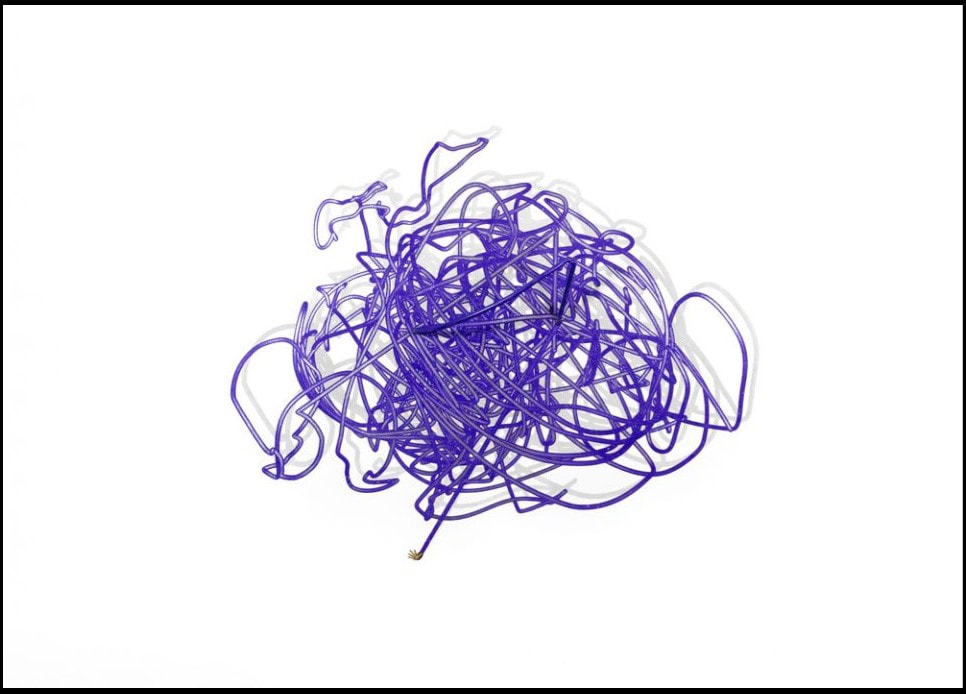

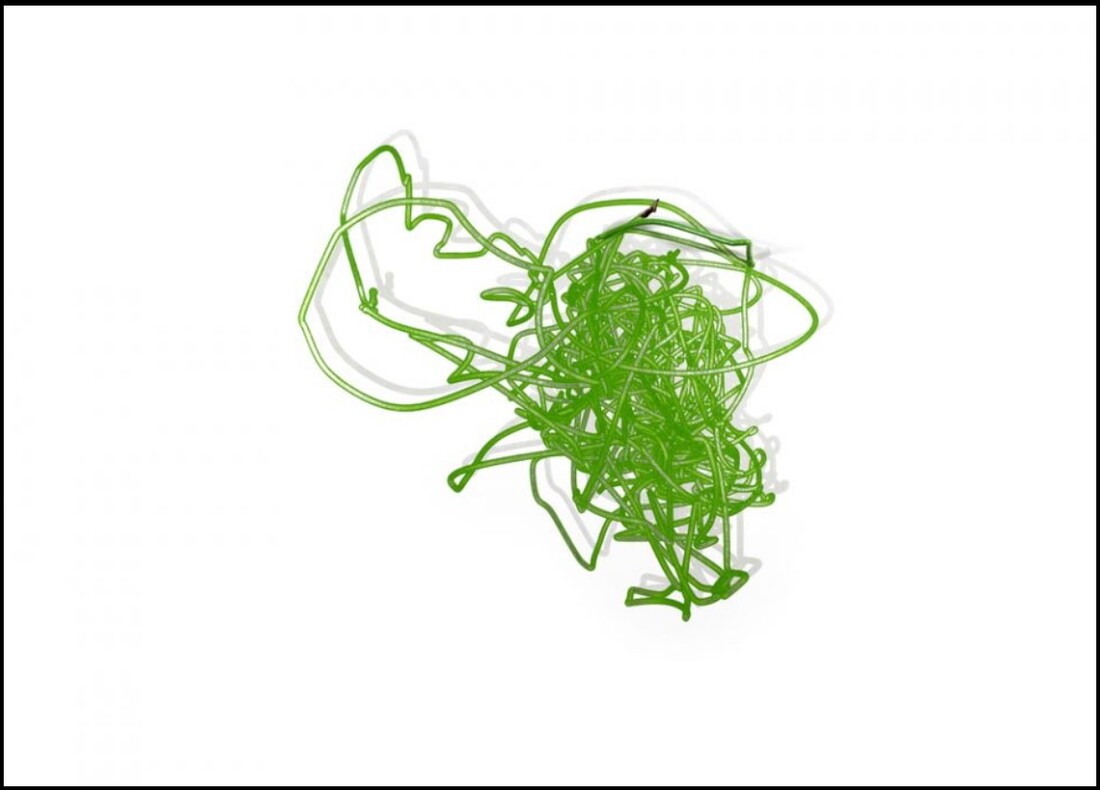

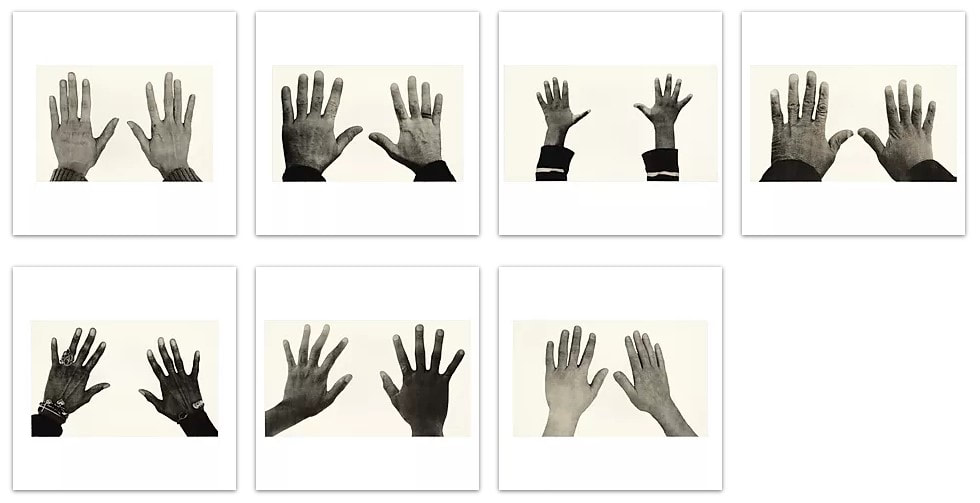

Ann ShaferI always wanted to do an exhibition about the audience. Portraying not the main attraction—the action on stage—but the people who are watching seems ripe for capturing a slice of life. The lookers being looked at flips convention. Voyeurism is a funny thing, alternately creepy and, what’s the opposite of creepy? Oh, pleasant. There are some great prints from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that would fit in this proposed exhibition nicely like Mary Cassatt’s In the Opera Box, 1879, Reginald Marsh’s Box at the Metropolitan, 1934, Joseph Hirsch’s Hecklers, 1943. Of course, there are plenty of paintings portraying audiences, too. My favorite is Tissot’s Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885. Though these images may seem quirky and quaint now, it is possible for an image of this type to cross over into social justice and to capture the zeitgeist. For me, one of the most searing group of images of an audience is Paul Fusco’s series taken in 1968 from the train carrying the body of Robert F. Kennedy from New York to Washington, D.C., for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The photographs capture an emotionally naked populace witnessing the end of optimism in the country. RFK’s assassination followed that of his brother, President Kennedy on November 22, 1963; Malcolm X on February 21, 1965; and Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968. RFK was shot just two months after Dr. King’s death, on June 5, 1968. By then, the country had seen more than its share of sorrow and senseless killing. The photographer, Paul Fusco, died last week, and it reminded me of how powerful the images are still. I marvel at how much emotion is conveyed across decades; they give me chills to this day. It may not surprise you to know that one of the photographs, a shot up North Broadway, just before the train dips underground on its approach into Penn Station in Baltimore, is one that got away. I pitched this photograph some years ago and got enough pushback to return it to the dealer. Part of the issue was that my colleagues weren’t convinced it was Baltimore in the photograph (of course it is), and the other had to do with vintage prints versus later reprints. Many curators seek and prefer to collect vintage prints, meaning the photographs were printed at the time they were shot. The photograph in question was a later printing, and thus was less desirable. I am certain Fusco wasn’t thinking in terms of museum collections in 1968. In fact, as a member of Magnum Photos, an international cooperative agency, he was on assignment for Look magazine, which published two of the photographs in black and white. The series was unknown until Aperture published it in 2008. Hence the later printings. In an earlier post I said I have never forgotten those that got away, and it’s true. To this day, when I see one of these works on the wall in some exhibition, I think “yes, I was right.” A few years after my failed pitch, I saw an exhibition of Fusco’s RFK train pictures at SFMoMA, and there was the North Broadway shot, front and center. Vindication. Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (North Broadway, Baltimore), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Family), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Paul Fusco (American, 1930–2020) Untitled (Western Maryland Railroad), from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed later Danziger Gallery Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926) In the Opera Box (No. 3), c. 1880 Etching, softground etching, and aquatint Sheet: 357 x 269 mm. (14 1/16 x 10 9/16 in.) Plate: 197 x 178 mm. (7 3/4 x 7 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Imrie de Vegh, 1949, 49.127.1 Reginald Marsh American (1898–1954) Box at the Metropolitan, 1934 Etching and engraving Sheet: 250 x 202 mm. (9 13/16 x 7 15/16 in.) Plate 322 x 252 mm. (12 11/16 x 9 15/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of The Honorable William Benton, 1959, 59.609.15 Joseph Hirsch (American, 1910–1981) The Hecklers, 1943–1944, published 1948 Lithograph Sheet 312 421 mm. (12 5/16 x 16 9/16 in.) Image: 251 x 388 mm. (9 7/8 x 15 ¼ in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2503 James Tissot (1836–1902) Women of Paris: The Circus Lover, 1885 Oil on canvas 147.3 x 101.6 cm. (58 x 40 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, 58.45 Ann ShaferCome with me down a rabbit hole to where the praying mantis lives. We will look at a 1946 print by Fred Becker, who was one of Hayter’s people. He worked as a shop tech and printer at Atelier 17 in the 1940s until he left to found the printmaking program at Washington University in St. Louis. I have been looking at and researching this American artist recently; I have been mulling over Kaleidoscopic Organism, 1946, for longer then I’d like to admit. It has befuddled me. I thought today I would lay out my thinking and take you along for the ride as I pick it apart and attempt to get inside the artist’s mind. Please know this is only my thinking—no guarantee that any of it is right! Kaleidoscopic Organism is an engraving and etching (both hard and softground) and is sizable at 17 5/8 x 14 3/4 (plate size). The image is wacky. An amoeba-like mass occupies the center around which swirl discs that hold open said amoeba to reveal its innards. In the background are radiating lines that create either a halo or a vortex. Within the mass’ interior we find (from the bottom moving upward): a balustrade or railing that is being built or repaired, a casement window handle, a keyhole holding the center of the being but there’s something going through it (a little Dr. Seussian figure, n’est ce pas?), and assorted architectural wire forms surmounted by what I see as a praying mantis. Praying mantis, hmmm. These majestic but aggressive insects were a shared subject among artists making surrealist prints at Atelier 17. I’ve included several prints of mantes by Atelier 17 artists for your viewing pleasure. With angular rear legs, triangular pivoting head, bulging eyes, and large, weirdly human forearms, mantis anatomy translates easily into line and action on the plate and offers interesting stand-ins for humans. But more to the point, the female mantis devours the male mantis after copulation (yikes!). They are also known to attack other insects (delightful). [For a good discussion about the Surrealists’ obsession with praying mantes, see William L. Pressly, “The Praying Mantis in Surrealist Art,” The Art Bulletin 60, no. 4 (December 1973): 600–615. And Ruth Markus. “Surrealism's Praying Mantis and Castrating Woman.” Woman's Art Journal 21, no. 1 (2000), 33–39. So, what about that praying mantis in Becker’s organism? I think we’ve got ourselves a vagina dentata, reflecting myths about fierce lady bits and male castration fears. Becker’s form is not toothed like Hayter’s Ceres, 1947–48 (image below), but its head that is just at the apex of the cavity cannot be overlooked. I will leave it there. Then, we must look at the bulk of the organism itself. At its bottom we find two feet, one with a shoe so worn that a big toe pops out of it. Until this moment, I could still believe we were dealing with a microscopic look at teeming life or a celestial big bang in process, but the feet snap us back to the immediate, visible world. What the heck? Ok, so here are my theories/questions about each element, which often have opposing possibilities. They are many and still swimming around in my brain. I welcome any thoughts that may clarify or further confuse the issues. 1. Is the background radiating to highlight the subject like a halo or is it a vortex we might fall into? 2. Are the discs holding the form open or running around its edges? Are they swirling like wheels or symbolizing something else? I see variously eyes, lemon slices, stained glass windows, military medals of honor, kaleidoscope parts. But could they be railway car wheels or shower heads—you see where I’m heading here, don’t you? 3. The interior elements are structural, manmade, and mechanistic (even the mantis). They are linked together like a Rube Goldbergian contraption. What’s up with the balustrade, the keyhole, and those wire apparatuses? I find it curious that the exterior discs read as organic while the interior elements read as mechanistic. There is something there just out of reach, but it will come to me. 4. The feet read as either comical (a hobo or circus clown), or as deadly serious (a wounded or dead soldier). 5. The title cannot be overlooked: Kaleidoscopic Organism (although I hate it when artists rely on titles to explicate the work—shouldn’t it hold up on its own?). The dictionary tells us that a kaleidoscope can symbolize one’s escape in times of difficulty and self-doubt; that it constantly generates changing symmetrical patterns from small pieces of colored glass and therefore symbolizes anything that changes constantly. Here is where I’ve ended up on meaning in Kaleidoscopic Organism. The title and the aforementioned definition of kaleidoscope bring me to World War II and its aftermath. At first glance, the print (made in 1946, the year after the war ended) looks comical: those gargantuan feet, the toe poking out of the shoe, the whirligigs and deeley boppers. What a smart way to pull us in. But then the praying mantis at its core turns it dark; the radiant, glowing halo turns into a vortex; the feet become those of a dead soldier; the organisms holding open the form reveal man’s mechanistic world symbolizing war, its machines, and their enabling of unbelievable cruelty and death. I suppose that contemporaneous viewers might read this work more quickly, but I believe it is imperative that we know and learn from history. It also serves to remind us that when looking at a work of art, it must be considered in context since artists can never be disassociated from the time in which they are working. Becker’s print is still stewing in my brain. If I come up with a better answer, I’ll let you know. Fred Becker (American, 1913–2004) Kaleidoscopic Organism, 1946 Etching, softground etching, and engraving Plate: 451 x 378 mm. (17 3/4 x 14 7/8 in.) Annex Galleries Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988) Cruelty of Insects, 1942 Engraving and softground etching Sheet: 230 x 288 mm. (9 1/16 x 11 5/16 in.); plate: 202 x 250 mm. (7 15/16 x 9 13/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Paul Mann, Towson, Maryland, BMA 1979.367 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1972) Praying Mantis, c. 1940s Engraving and softground etching Plate: 394 x 279 mm. (15 ½ x 11 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum: Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.4 Werner Drewes (American, born Germany, 1899–1985) Praying Mantis, 1944, printed 1975 Engraving and softground etching Plate: 200 x 302 mm. (7 7/8 x 11 7/8 in.) Annex Galleries Clinton Blair King (American 1901–1979) Praying Mantis, c. 1945 Etching and aquatint Plate: 277 x 200 mm (10 7/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2866 Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988) Ceres, 1947–48 Engraving, softground etching, and scorper Printed in black (intaglio), and yellow (screen, relief) 605 x 390 mm. (23 7/8 x 15 3/8 in.) Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires Ann ShaferHere’s another one that got away. And at my very last opportunity before leaving the museum, too. Rashaad Newsome’s 2016 set of lithographs were front and center in Tamarind’s booth at the 2017 Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. The five lithographs are part of a larger project that begins with a performance of five dancers voguing, which was captured by an Xbox Kinect the artist reprogrammed. Five classic voguing dance forms were performed. The energetic swirls of their movements were captured digitally and subsequently translated into both sculptures and prints. Check out this video of Tornado Revlon. In the performance, each dancer—all of whom are well known in the voguing world—performs a different move: a catwalk is performed by Star Revlon; rapid hand movements are performed by Tornado Revlon; duck walking is performed by Justin Monster Labeija; spin dips are performed by Davon Amazon; and floor work is performed by Jamel Prodigy. For the Tamarind lithographs, the digitally tracked movements are printed in different colors, and a tiny plastic body part that indicates which part was tracked is collaged onto each print. They are 29 ¾ x 42 inches each. I knew they would both have wall power and draw people in. Newsome’s work looks at agency and privilege, asking who gets it, when, and why. Vogue balls, events that became widely known through the 1990 film Paris is Burning, is currently the subject of an FX series called Pose, which is streaming on Netflix, Amazon Prime, and elsewhere. I imagine that people in the voguing world have mixed feelings about being put under a microscope and portrayed by actors, particularly since vogue balls have always been recognized as safe spaces for Black and queer people. But that moniker “safe space” implies outsiders aren’t welcome. What do you do when Hollywood comes calling? Newsome’s performance regains agency for the performers themselves (Newsome is a part of the community) and brings it to the fine art world. Just as balls are safe spaces, I would postulate that artmaking is a safe space, too. In their need to investigate themes, problems, and ideas deeply, artists must have their own safe spaces where ideas are put through the conceptual sausage grinder and are transformed into something that starts conversations and spurs thinking and feeling. I like the parallels. You may recall I love the idea of taking dance/movement to the walls of a gallery (see my post about Trisha Brown). Works that cross disciplines have always interested me. But also because performance art is difficult to collect because of its ephemerality, I appreciate creative ways of capturing it. Just as Stan Shellabarger’s walking book (see earlier post) was the product of its own creation, Newsome’s prints capture performance through digital tracking technology. I am not particularly interested in performance art through documentary photographs. Newsome’s tracked movements translated into a jumble of frenetic energy are more evocative of the performance than any photograph could ever be. I thought it would be a great fit for the collection. Truthfully, I can’t recall which straw man quashed the acquisition. While I got used to disappointments over the years, I can still conjure the feeling of frustration. I used to always say: “I should have been a collector.” Oh well, guess I’ll just keep writing about it. Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Five multi-color lithographs with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet (each): 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Catwalk (Star Revlon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Hands (Tornado Revlon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Duck Walking (Juston Monster Labeija), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Spin Dips (Davon Amazon), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Rashaad Newsome (American, born 1979) Published by Tamarind Institute Floor Performance (Jamel Prodigy), from the portfolio FIVE SFMOMA, 2016 Color lithograph with 3D-printed and collage elements; and silver-leaf or pearlescent dusting Sheet: 29 3/4 x 42 inches Ann ShaferRecently I was google-alerted to an ARTNews article about the Baltimore Museum of Art’s recent round of contemporary acquisitions, which, during its “year of the woman,” are all by women, mostly of color. Most of the artists are likely unfamiliar to you—they were to me. Let me be clear: I applaud the effort; it’s all good. But it made me think back to all the acquisitions meetings during which I proposed works of art only to be turned down because the artists were unknown to my colleagues. That reason to say no, “I’ve never heard of them,” made me mentally design a pie chart. There is a narrow slice of pie that represents contemporary artists my colleagues were interested in, and then there is the rest of the pie filled with artists making meaningful work. They just aren’t represented by Hauser & Wirth, Gagosian, or David Zwirner. I once was told: “There is a difference between contemporary art and art made today.” I always felt this was seriously shortsighted. This points to the beauty of prints and other works on paper since they are considerably more affordable than paintings, sculpture, installations, video art, and such. The price point of paintings, etc., is often a stretch for all but the best endowed museums, and the ability to acquire these kind of objects is limited. Whereas the curators in these areas must choose VERY carefully, curators of works on paper have it easier in collecting outside the sliver of pie that the contemporary curators are held to. The print curator is always thinking about the content and usefulness of a particular object rather than whether it’s by a superstar artist (at least I am). Over the years, there have been quite a few works I failed to get into the collection. I have never forgotten them. One of the ones that got away was close enough that we brought it into the museum for consideration. (Usually if it was a no, the no came long before we brought works in.) It was a portfolio of prints by Damon Davis called All Hands on Deck, 2015. Here’s the backstory. Davis is a native of East St. Louis. Following the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, and events that followed—peaceful protests that turned ugly—Davis took photographs of the hands of a variety of protesters up, in a turnabout of gesture. Rather than hands up as surrender, they are hands up in protest. The photographs were printed out on large sheets and wheat pasted onto the boarded-up storefronts along West Florissant Avenue (with the permission of the store owners), which had become ground zero of the protests. Subsequently, Davis worked with Wildwood Press’ Maryanne Simmons to create a fine art edition of seven pairs of hands. The moment I saw the announcement of its publication, I fired off an inquiry about the portfolio. It seemed like a no-brainer for the Baltimore Museum given the city’s unrest following the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015, less than a year after Michael Brown’s death. Talk about parallels. (Susan Tallman wrote an excellent article on Davis’ portfolio in Art in Print, which you can find here.) When the prints arrived, my colleagues took issue with the quality of the images. Davis had retained the pixilation and choppiness of the edges from the wheat paste posters. I explained that Davis had photoshopped the images quickly in an effort to get them up on storefronts and had decided to retain that same look in the fine art edition. I had absolutely no doubt that they would look fantastic on the wall—in curator parlance we would say they have wall power. Even better, they are both specific to Ferguson and universal. They stand as a monument to protests against police brutality across the country and they are as powerful today as they were in 2015. I regret my failure for the collection. And even worse: we had full funding for the portfolio from a donor. Damon Davis (American, born 1985) Published by Wildwood Press All Hands on Deck, 2015 Portfolio of seven lithographs Sheet (each): 813 x 1232 (32 x 48 ½ in.) |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed