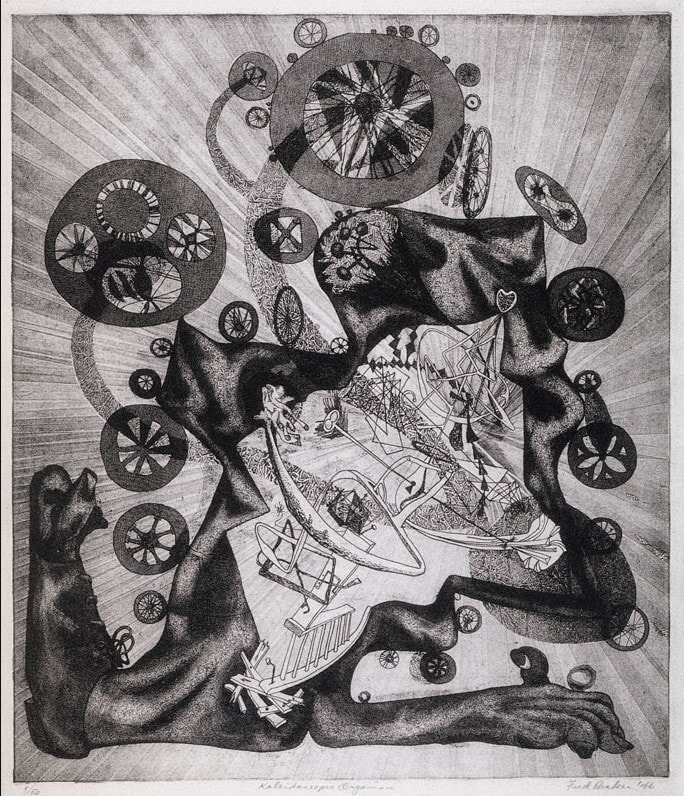

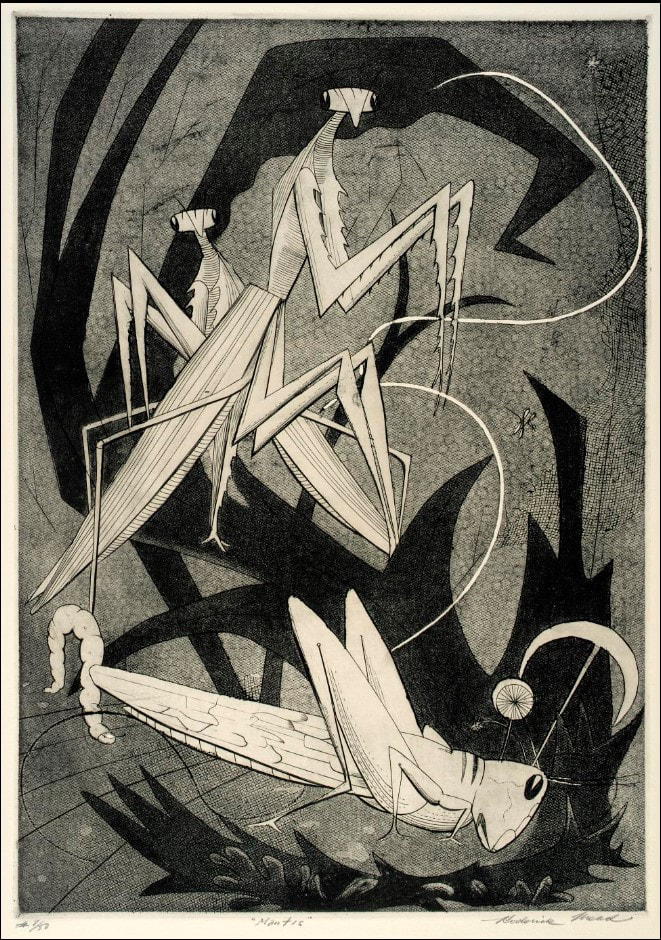

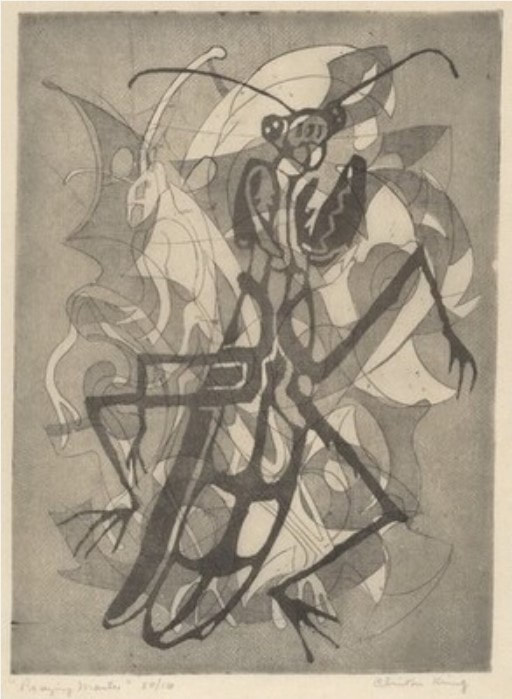

Ann ShaferCome with me down a rabbit hole to where the praying mantis lives. We will look at a 1946 print by Fred Becker, who was one of Hayter’s people. He worked as a shop tech and printer at Atelier 17 in the 1940s until he left to found the printmaking program at Washington University in St. Louis. I have been looking at and researching this American artist recently; I have been mulling over Kaleidoscopic Organism, 1946, for longer then I’d like to admit. It has befuddled me. I thought today I would lay out my thinking and take you along for the ride as I pick it apart and attempt to get inside the artist’s mind. Please know this is only my thinking—no guarantee that any of it is right! Kaleidoscopic Organism is an engraving and etching (both hard and softground) and is sizable at 17 5/8 x 14 3/4 (plate size). The image is wacky. An amoeba-like mass occupies the center around which swirl discs that hold open said amoeba to reveal its innards. In the background are radiating lines that create either a halo or a vortex. Within the mass’ interior we find (from the bottom moving upward): a balustrade or railing that is being built or repaired, a casement window handle, a keyhole holding the center of the being but there’s something going through it (a little Dr. Seussian figure, n’est ce pas?), and assorted architectural wire forms surmounted by what I see as a praying mantis. Praying mantis, hmmm. These majestic but aggressive insects were a shared subject among artists making surrealist prints at Atelier 17. I’ve included several prints of mantes by Atelier 17 artists for your viewing pleasure. With angular rear legs, triangular pivoting head, bulging eyes, and large, weirdly human forearms, mantis anatomy translates easily into line and action on the plate and offers interesting stand-ins for humans. But more to the point, the female mantis devours the male mantis after copulation (yikes!). They are also known to attack other insects (delightful). [For a good discussion about the Surrealists’ obsession with praying mantes, see William L. Pressly, “The Praying Mantis in Surrealist Art,” The Art Bulletin 60, no. 4 (December 1973): 600–615. And Ruth Markus. “Surrealism's Praying Mantis and Castrating Woman.” Woman's Art Journal 21, no. 1 (2000), 33–39. So, what about that praying mantis in Becker’s organism? I think we’ve got ourselves a vagina dentata, reflecting myths about fierce lady bits and male castration fears. Becker’s form is not toothed like Hayter’s Ceres, 1947–48 (image below), but its head that is just at the apex of the cavity cannot be overlooked. I will leave it there. Then, we must look at the bulk of the organism itself. At its bottom we find two feet, one with a shoe so worn that a big toe pops out of it. Until this moment, I could still believe we were dealing with a microscopic look at teeming life or a celestial big bang in process, but the feet snap us back to the immediate, visible world. What the heck? Ok, so here are my theories/questions about each element, which often have opposing possibilities. They are many and still swimming around in my brain. I welcome any thoughts that may clarify or further confuse the issues. 1. Is the background radiating to highlight the subject like a halo or is it a vortex we might fall into? 2. Are the discs holding the form open or running around its edges? Are they swirling like wheels or symbolizing something else? I see variously eyes, lemon slices, stained glass windows, military medals of honor, kaleidoscope parts. But could they be railway car wheels or shower heads—you see where I’m heading here, don’t you? 3. The interior elements are structural, manmade, and mechanistic (even the mantis). They are linked together like a Rube Goldbergian contraption. What’s up with the balustrade, the keyhole, and those wire apparatuses? I find it curious that the exterior discs read as organic while the interior elements read as mechanistic. There is something there just out of reach, but it will come to me. 4. The feet read as either comical (a hobo or circus clown), or as deadly serious (a wounded or dead soldier). 5. The title cannot be overlooked: Kaleidoscopic Organism (although I hate it when artists rely on titles to explicate the work—shouldn’t it hold up on its own?). The dictionary tells us that a kaleidoscope can symbolize one’s escape in times of difficulty and self-doubt; that it constantly generates changing symmetrical patterns from small pieces of colored glass and therefore symbolizes anything that changes constantly. Here is where I’ve ended up on meaning in Kaleidoscopic Organism. The title and the aforementioned definition of kaleidoscope bring me to World War II and its aftermath. At first glance, the print (made in 1946, the year after the war ended) looks comical: those gargantuan feet, the toe poking out of the shoe, the whirligigs and deeley boppers. What a smart way to pull us in. But then the praying mantis at its core turns it dark; the radiant, glowing halo turns into a vortex; the feet become those of a dead soldier; the organisms holding open the form reveal man’s mechanistic world symbolizing war, its machines, and their enabling of unbelievable cruelty and death. I suppose that contemporaneous viewers might read this work more quickly, but I believe it is imperative that we know and learn from history. It also serves to remind us that when looking at a work of art, it must be considered in context since artists can never be disassociated from the time in which they are working. Becker’s print is still stewing in my brain. If I come up with a better answer, I’ll let you know. Fred Becker (American, 1913–2004) Kaleidoscopic Organism, 1946 Etching, softground etching, and engraving Plate: 451 x 378 mm. (17 3/4 x 14 7/8 in.) Annex Galleries Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988) Cruelty of Insects, 1942 Engraving and softground etching Sheet: 230 x 288 mm. (9 1/16 x 11 5/16 in.); plate: 202 x 250 mm. (7 15/16 x 9 13/16 in.) Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Paul Mann, Towson, Maryland, BMA 1979.367 Roderick Mead (American, 1900–1972) Praying Mantis, c. 1940s Engraving and softground etching Plate: 394 x 279 mm. (15 ½ x 11 in.) Smithsonian American Art Museum: Gift of Mrs. Roderick Mead, 1974.122.4 Werner Drewes (American, born Germany, 1899–1985) Praying Mantis, 1944, printed 1975 Engraving and softground etching Plate: 200 x 302 mm. (7 7/8 x 11 7/8 in.) Annex Galleries Clinton Blair King (American 1901–1979) Praying Mantis, c. 1945 Etching and aquatint Plate: 277 x 200 mm (10 7/8 x 7 7/8 in.) National Gallery of Art: Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 2008.115.2866 Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988) Ceres, 1947–48 Engraving, softground etching, and scorper Printed in black (intaglio), and yellow (screen, relief) 605 x 390 mm. (23 7/8 x 15 3/8 in.) Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed