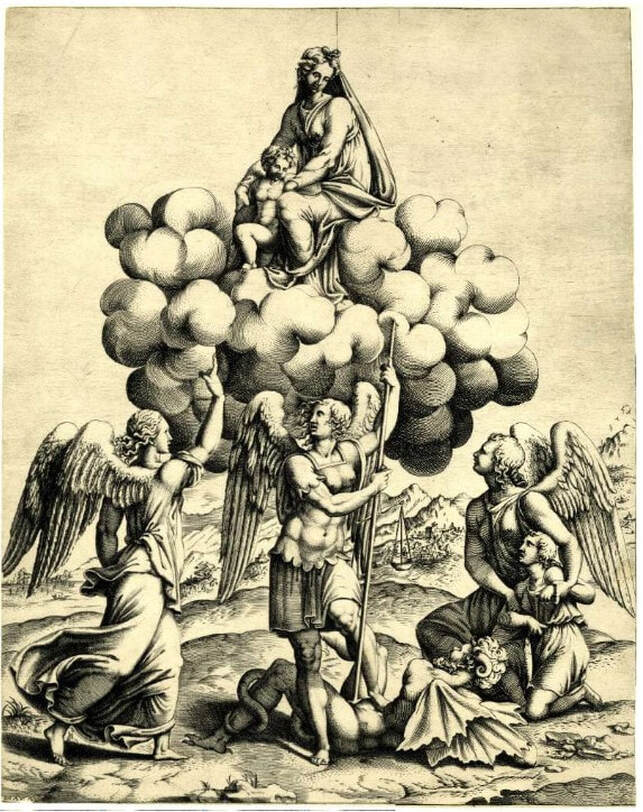

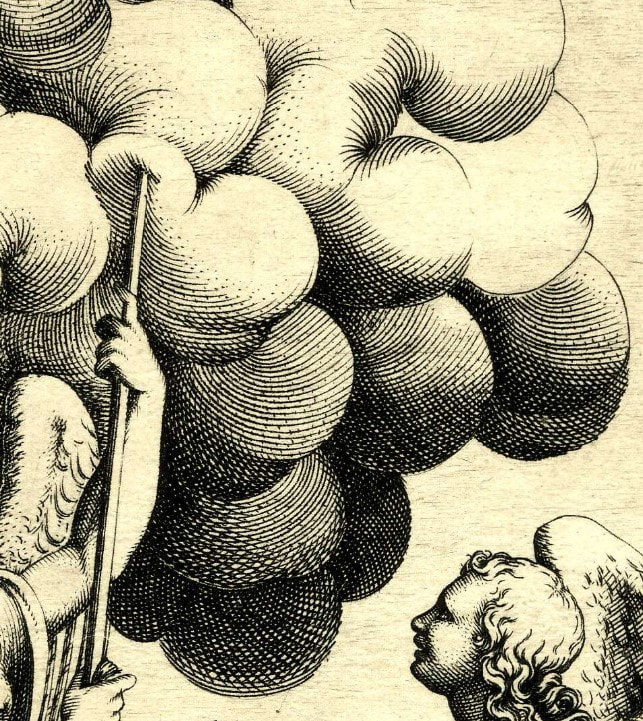

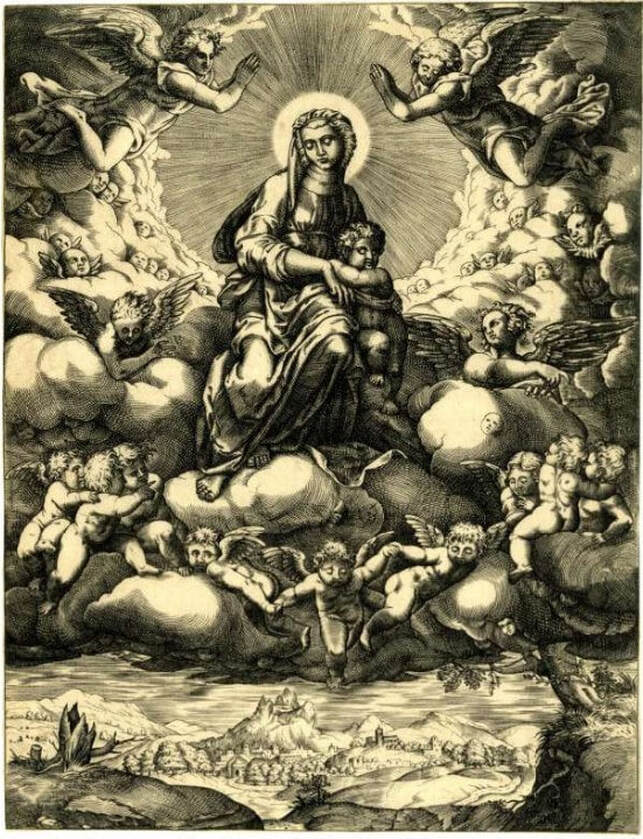

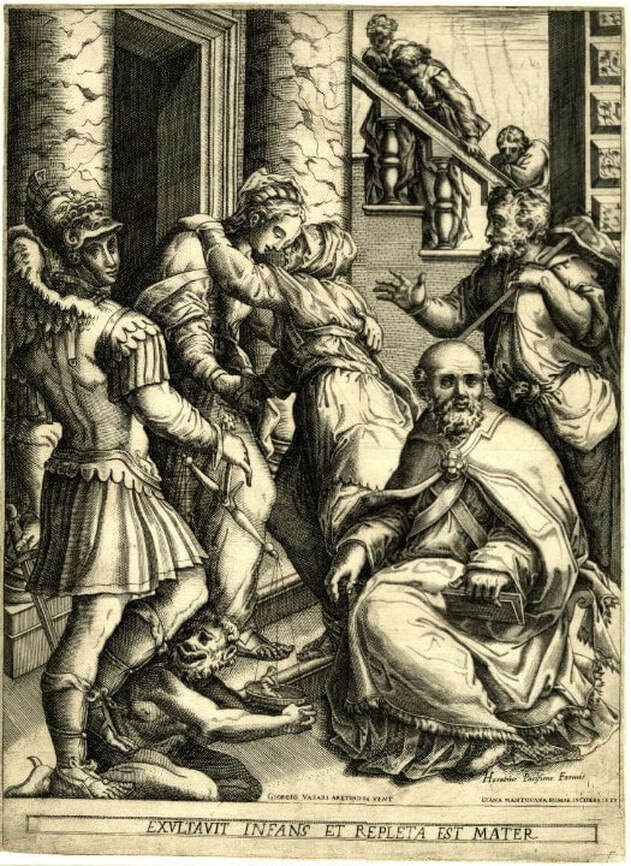

Ann Shafer In recognition of the one hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the nineteenth amendment granting women the right to vote, the BMA has just concluded its year of the woman during which it exhibited and acquired only work by female artists. I applaud the effort and am happy to see they have shown some terrific artists during 2020. It is pretty easy in contemporary art to find excellent female artists. Despite the fact that women still account for less than 50% of exhibitions across US museums, the problem is at least recognized. It is much harder to find huge numbers of women working in the early centuries of Western art—say, fourteenth through eighteenth centuries. In the early history of prints, when women artists are noted, most are members of a print and publishing family or are amateur artists. Remember, women were barred from art schools and institutions and there was a serious barrier to entry on multiple fronts. More research is emerging about these should-be-better-known artists. But it takes time and a lot of work. In the next few posts I want to introduce you to a few early female printmakers. Today, please meet Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588). Part of the reason we know about Scultori’s work at all is that she signed her prints, which she did from her earliest known composition, The Continence of Scipio, 1542, to her last. The existence of this first dated print has thrown into question her birth date, which is usually noted as 1536. A birth date in the late 1520s is more likely given the math--most of us would agree that accomplishing an engraving at age six is unlikely, no matter how good she was. Scultori was one of four children of Giovanni Battista Scultori, who lived and operated a print workshop in Mantua. She learned printmaking in her father’s studio and executed a number of prints reproducing the compositions of several artists including Giulio Romano, who was a friend and neighbor. Romano was a pupil of Raphael and was the official artist of Duke Federico Gonzaga of Mantua. Scultori's prints helped spread Romano's renown far and wide. Scultori received her first public recognition as an engraver in Giorgio Vasari's second edition of Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects) in 1568, an early codification of Italian art history. In it Vasari talks about meeting the artist and her father on a trip to Mantua: "To Giovanbattista Mantovano, an engraver of prints and an excellent sculptor, whom we have spoken of, in the Vita of Giulio Romano and that of Marcantonio Bolognese, two sons were born, who engrave prints on copper divinely; and what is more wondrous, a daughter named Diana, who also engraves very well, which is a wondrous thing: and I who saw her, a very young and gracious young girl, and her works which are very beautiful, was astounded." This is a huge deal. Scultori engraved some sixty-two prints (that we know of), mainly of religious and mythological subjects. With her architect husband, Francesco Capriani da Volterra, she moved to Rome in 1575, where she received a Papal Privilege to make and market her own work. From the middle of the sixteenth century print publishers applied for privileges for specific prints or for all of their publications, which gave a legal base for prosecution in case of breach of the privilege. It must have been remarkable for the Pope to give Scultori the privilege on all her prints, which she signed “Diana” or “Diana Mantuana” (indicating she hailed from Mantua). Later, she married another architect, Giulio Pelosi, after her first husband died in 1594. She herself died in 1612. I imagine we would know absolutely nothing about her if she had not insisted on signing her works. Did she understand that any unsigned work would be assumed to be by a man? I am guessing she did, and that that confidence was encouraged by her father and brothers in the family printshop. I would love to have been a fly on the wall in that workshop. Don’t miss how she articulate those clouds in the last detail: stylized and hilarious, in the best way.  Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588), after Giulio Romano (Italian, c. 1499–1546). The archangels Michael, Gabriel and Raphael adoring the Virgin and Child who occur above seated on a cloud, 1547–1612. Engraving. Sheet (trimmed to platemark): 340 x 270 mm. British Museum: Bequest of Sir Hans Sloane, 1799, V,8.12.  [DETAIL] Diana Scultori (Italian, 1536–1588), after Giulio Romano (Italian, c. 1499–1546). The archangels Michael, Gabriel and Raphael adoring the Virgin and Child who occur above seated on a cloud, 1547–1612. Engraving. Sheet (trimmed to platemark): 340 x 270 mm. British Museum: Bequest of Sir Hans Sloane, 1799, V,8.12.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed