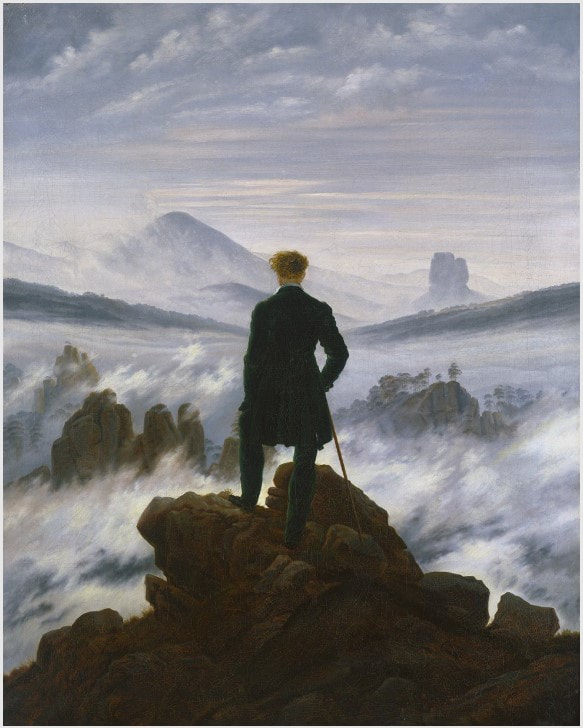

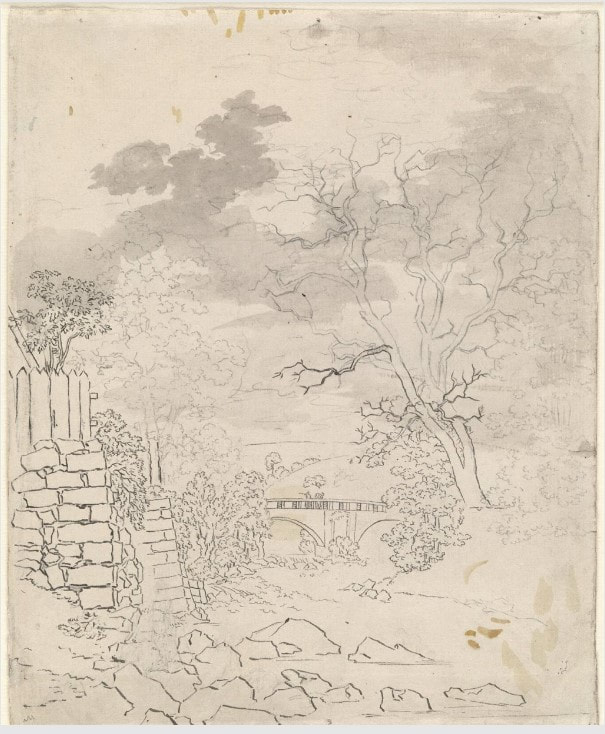

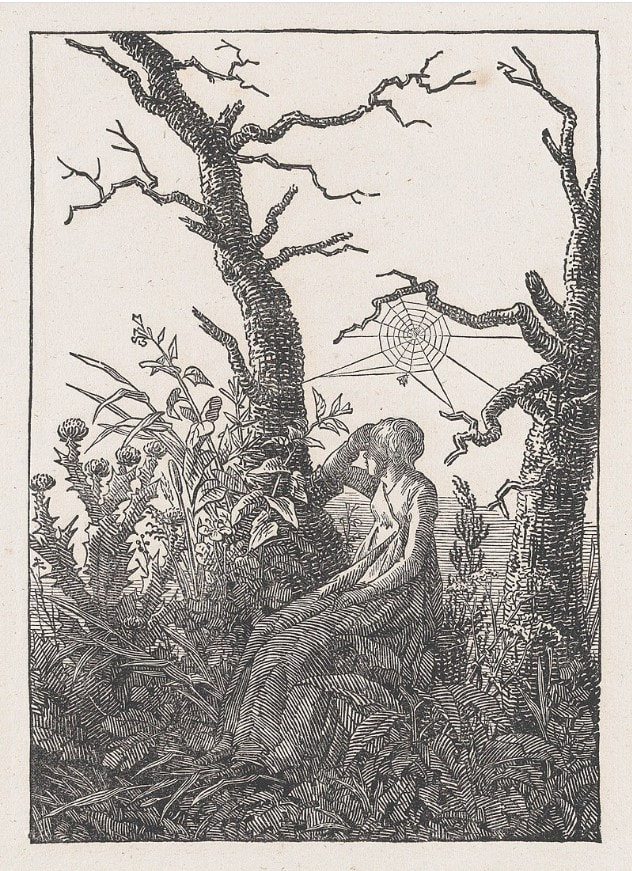

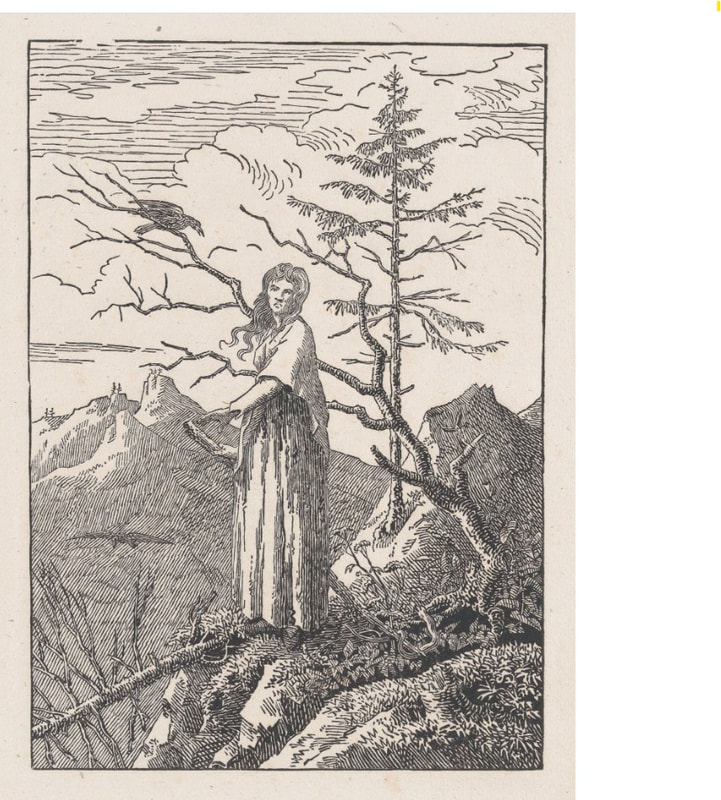

Ann ShaferOn a dreary, rainy Sunday amid a global health and economic crisis, showcasing a melancholic artist seems like just the thing. Caspar David Friedrich, a German artist working at the turn of the nineteenth century, is known for his stark, romantic visions of landscape. In a well-known painting, Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, painted around 1817, he captured the lone figure perched on a rocky outcropping above a vast, open landscape. The composition is constructed of various real elements by Friedrich, but nowhere can one stand on these rocks and see this specific view. But he has constructed the painting beautifully. The figure has his back to us as if he has led us to this spot and we have just arrived. The fog enhances the feeling of solitude. No tree is near him to help ground us and frame the picture. The middle ground mountains roll into the man’s chest bringing us to the heart of the matter (see what I did there?). The final set of mountains intersect with the man’s head, which barely rises above them. This is the sublime at its best. Humans are wired to feel expansive and hopeful at seeing a wide-open prospect such as this. (I’m taking a deep breath as I look at it.) With compositional elements converging in the man’s heart and head, this image speaks directly to the Romantic. For me, there is both a melancholic and hopeful feeling. And maybe that’s Friedrich’s magic: that his paintings can’t help but make us feel something. This painting has stuck with me since Art History 101, although I have never seen it in person. Field trip to Hamburg when this is over and we can travel again? I have always felt German Romanticism had a parallel movement in British landscapes in watercolor and in oil at this same time. I suspect the driving forces between the developments is similar but not identical. (I am no scholar of German Romanticism—please take this with a grain of salt.) But I love Friedrich’s ink wash drawings and watercolors. They are so reminiscent of those by British artists like John Ruskin, but they also can have a starkness and modernity to them that continues to intrigue me. Apparently, Friedrich’s output as an artist was little known during his lifetime and he was “discovered” only at the beginning of the twentieth century. One way an artist might try to enhance his stature was to create and publish prints that could be distributed widely. Friedrich made a pair of prints using his woodworker brother, Christian, as the formschneider (the block cutter). Woman with the Raven on the Abyss and Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, 1803, were entered in an 1804 exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden. I’m not sure about their reception, but it is pretty clear that Christian was not a great woodcutter. When asked by Christian if he would produce further works for transfer to woodcut, the artist declined, writing, "ask another artist." And yet, in Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, I still appreciate the composition: a lone woman sits between two bare trees (blasted tree, anyone?), while above her in the branches is a large spider web. What a creepy, potent, and weird image. It seems like just the kind of quirky print one would find in the Garrett Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art. But alas, it is not in that mammoth collection. For over a decade I kept my eyes open for an impression of the spider’s web print to come on the market (well, I didn’t hunt one down, but it was always in the back of my mind). Feeling certain the museum would never get a hold of a painting or drawing by Friedrich, having one of the prints seemed like a great way to get him into the collection. Plus, the print would have many friends, not the least of which is Dürer’s Melancholia I. Good company, indeed. Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer), c. 1817 Oil on canvas 94.8 cm × 74.8 cm. (37.3 × 29.4 in.) Hamburger Kunsthalle, HK-5161 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) An Owl on a Coffin (Eine Eule auf einem Sarg), 1835–38 Pen and gray ink, brown wash, and graphite 385 x 383 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41119 Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald 1774–1840 Dresden) Gate in the Garden Wall (Pforte in der Gartenmauer), c. 1828 Watercolor over graphite 122 x 185 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41123 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Sea with Rising Sun—Morning of Creation (Meer mit aufgehender Sonne—Schöpfungsmorgen), c. 1826 Brown wash over graphite 187 x 265 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41120 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Bridge over Brook (Bach mit Brücke), c. 1799 Pen and gray ink and gray wash over graphite 270 x 220 mm Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, 41091 Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Hill at Bruchacker near Dresden (Hügel mit Bruchacker bei Dresden), 1824/25 Oil on canvas 22.2 x 30.4 cm Hamburger Kunsthalle, HK-1055 Christian Friedrich (German, 1770–1843) after Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Woman with Spider’s Web Between Bare Trees, 1803 Woodcut Image: 170 x 120 mm (6 11/16 x 4 5/8 in.) Sheet: 260 x 193 mm (10 ¼ x 7 5/8 in.) Art Institute of Chicago: Alfred E. Hamill Collection, 1955.1031 Christian Friedrich (German, 1770–1843) after Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774–1840) Woman with a Raven, 1803 Woodcut Image: 170 x 119 mm. (6 11/16 x 4 11/16 in.) Sheet: 244 x 192 mm. (9 5/8 x 7 9/16 in.) Metropolitan Museum of Art: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund 1927, 27.11.3

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed