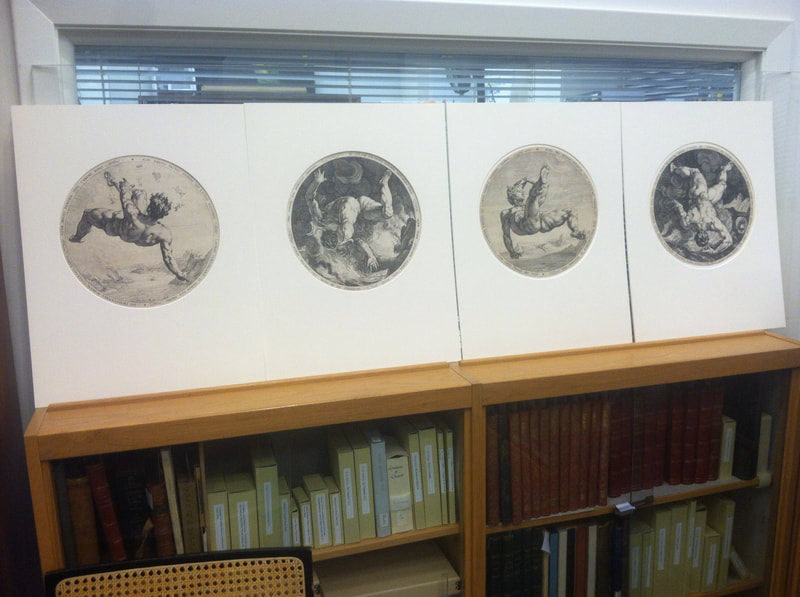

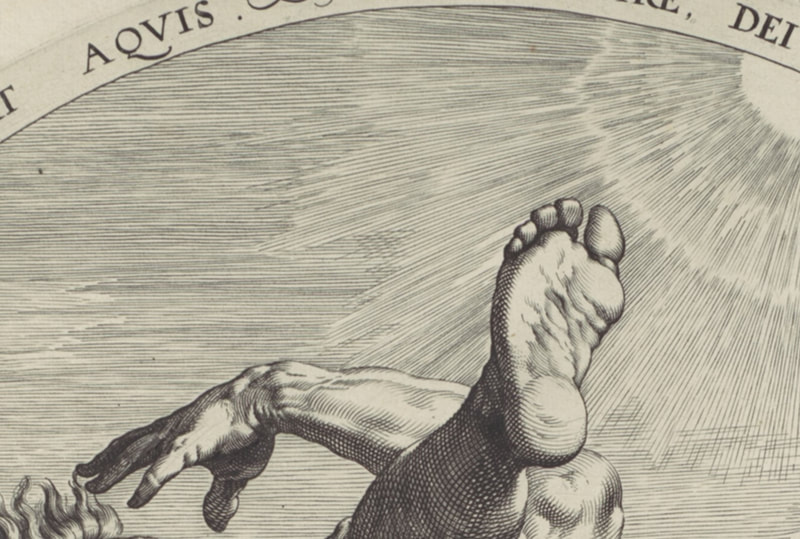

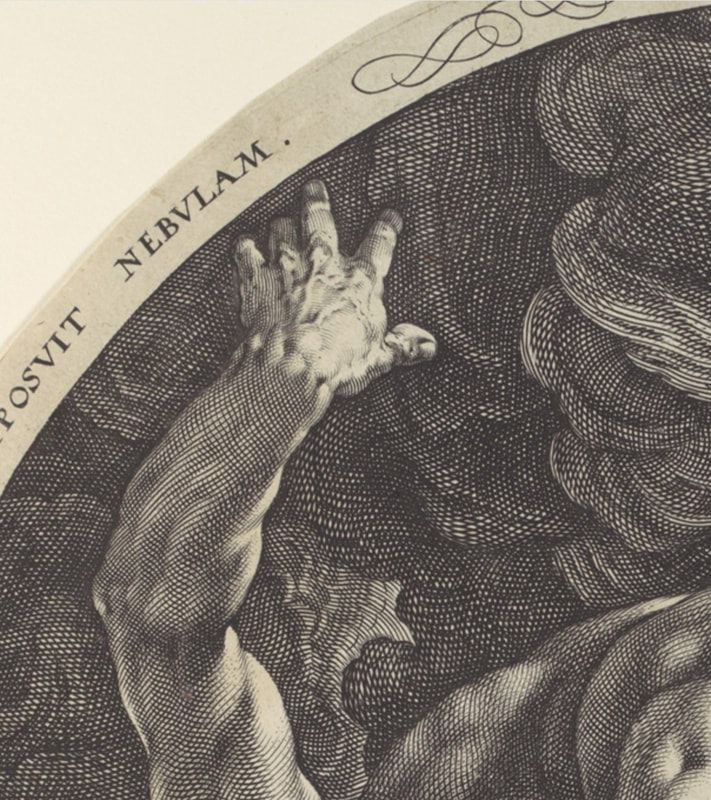

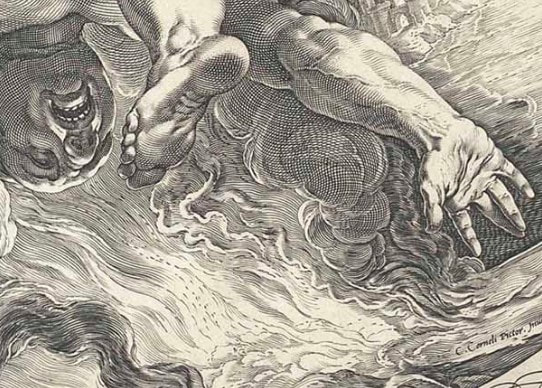

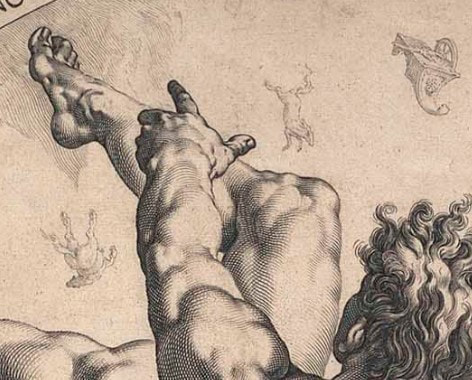

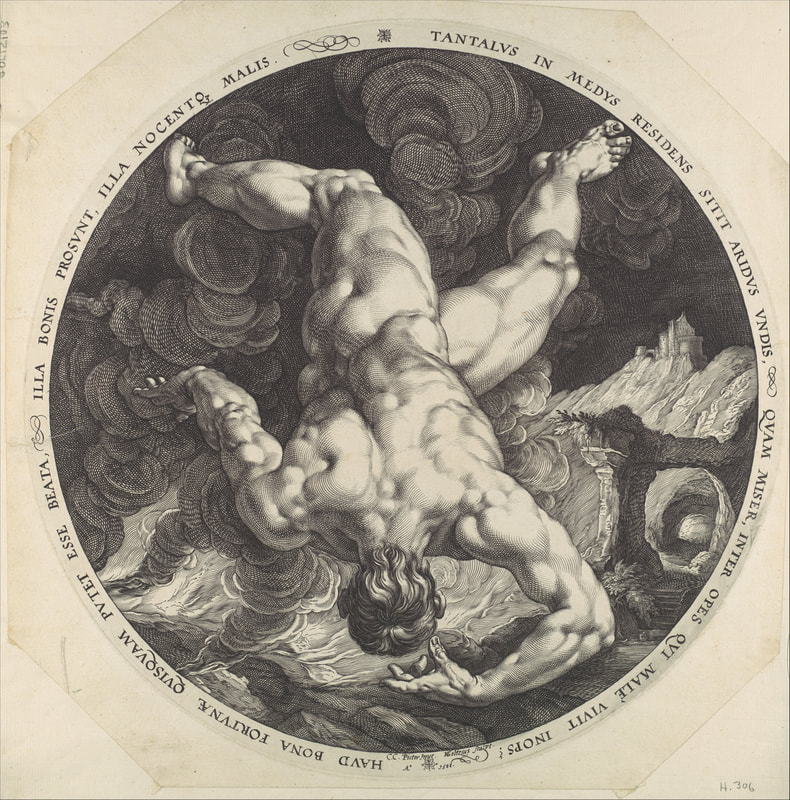

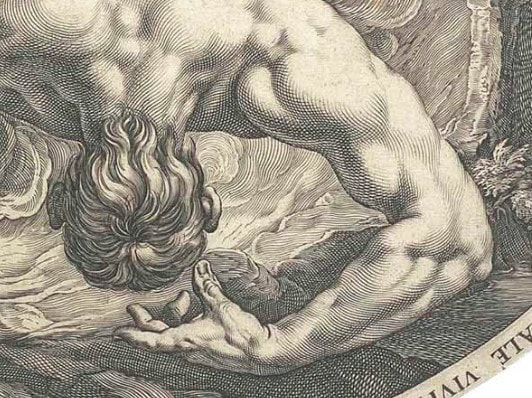

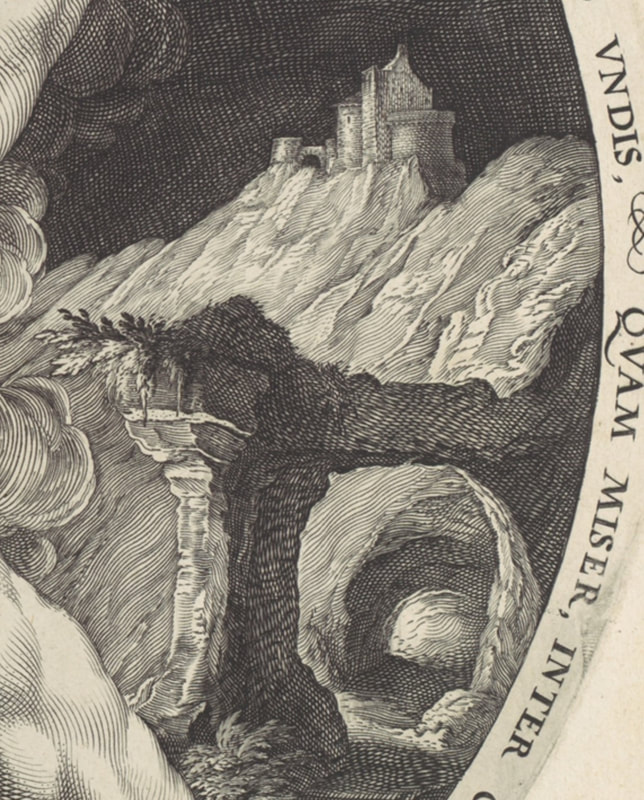

Ann Shafer While teaching young artists about prints, it’s easy to think they won’t respond to works made before 1960, but they can and do. There is a quartet of engravings from 1588 called The Disgracers that were always a highlight in Tru Ludwig’s History of Prints class. They are by Hendrick Goltzius and portray four male nude figures falling. Each engraving offers a muscular male in different views of nearly the identical pose. The four men are Icarus, Ixion, Phaethon, and Tantalus. Each of them had tried to enter the realm of the gods and were sentenced to eternal torture for their hubris. Kinda like the ancient Greek version of the fall of man.

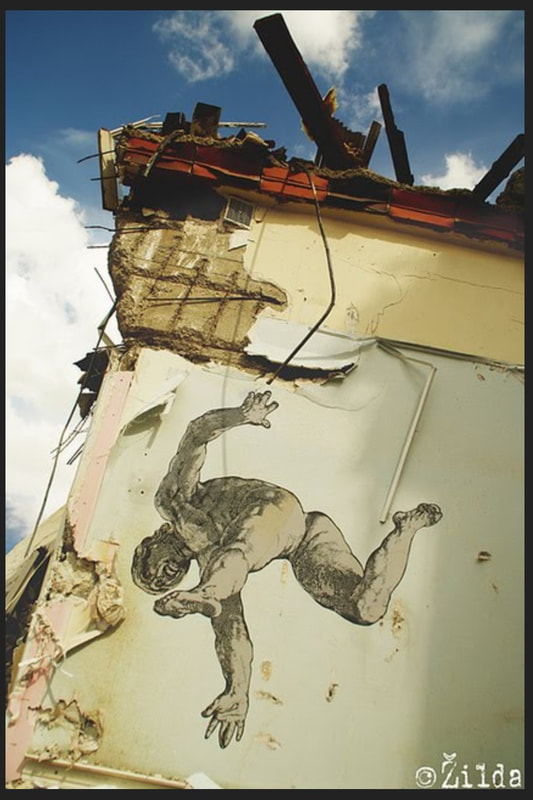

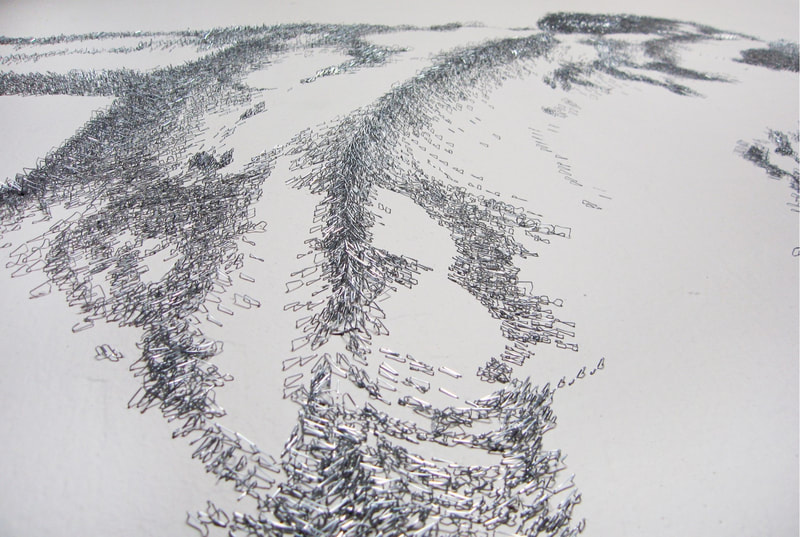

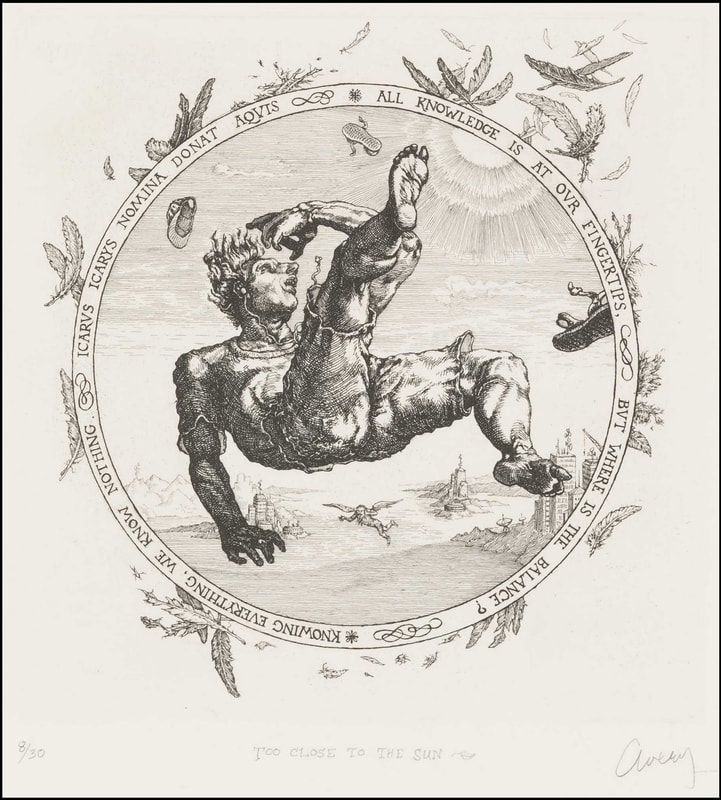

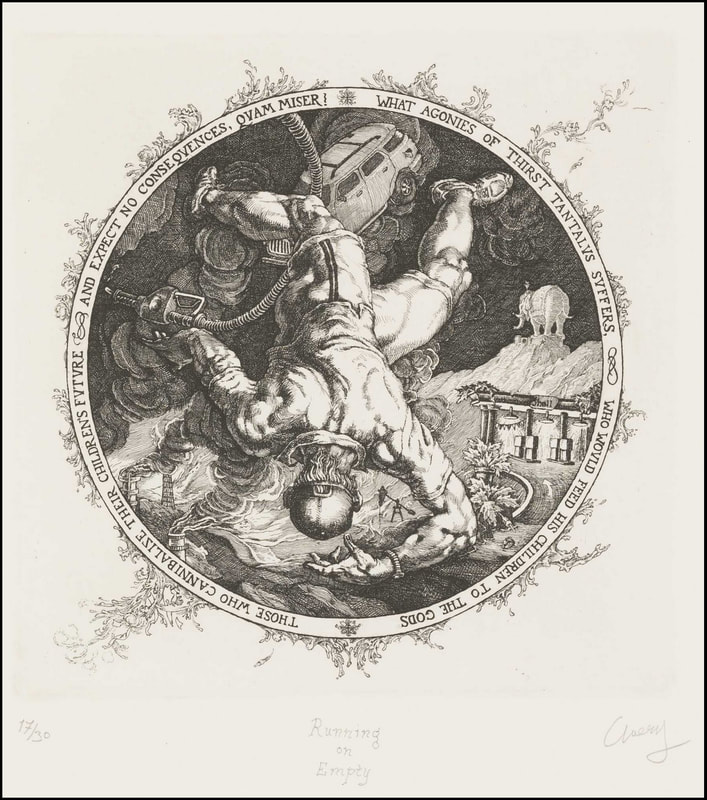

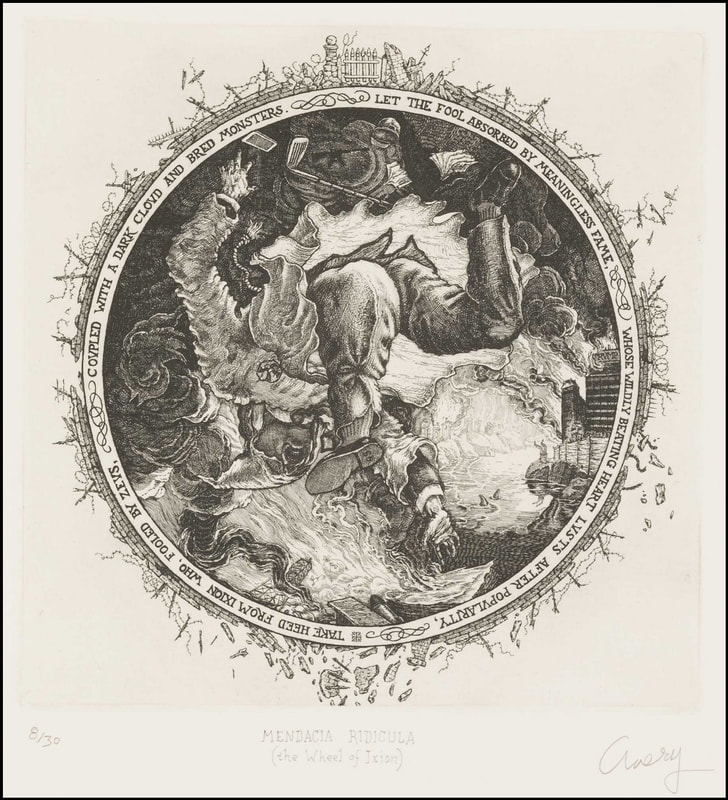

I’m guessing the students reacted to the same things I do in the prints: the artist’s audacity in portraying figures with such weird and difficult foreshortening; describing textures and patterns with surprisingly regimented engraved marks; giving a convincing sense of falling; portraying gentlemen-bits, as it were. (I can’t recall another example of such views of male nudes. Let me know if you can.) I also respond to them as a captured moment that tells the whole story of each flawed character without much context or narrative. I love the tondo shape (why aren’t they referred to simply as round?), and the text that runs around the circumference. It’s almost like we are looking through a telescope at them falling through the sky. The perspective and compositions are so startling after looking at standing figure after standing figure, they always elicited oohs and ahhs from the students. One might think the set of four would come to the museum together, having been originally collected as a group. But when I arrived at the museum there were only three of the four already in the collection and they all were, oddly, from different gifts. The missing print was Phaethon. I’m sure I wasn’t the only curator ever to work in the collection who kept an eye out to acquire the fourth print, but it took seven years to find one. It was like finding the long-lost last piece of the puzzle, and it still makes me expel a long sigh to think of them all together. There is just something wonderful about being able to show all four to students and visitors in the study room. The Disgracers are so well known to scholars of Western printmaking, you don’t even need to mention the artist’s name. Subsequent artists have been inspired by their compositions and messages and have borrowed from them to create their own take on them. For instance, there is a street artist in France named Žilda whose 2010 Liber Casus features wheat-pasted paintings of falling figures installed on buildings and bridges in Paris, Rennes, and Belgrade. And there is another artist, Baptiste Debombourg, who in 2012 created a mural based on Phaethon from The Disgracers using many thousands of staples. Yes, staples. Lawrence Goedde sums up their use of the falling figure well: “For both, the artifice of Goltzius’s series clearly provokes, intrigues, and challenges as they adapt his imagery to new purposes. Žilda sees the falling figures pasted high above passersby in urban settings as destabilizing the familiar world of the streets, provoking reflection on falling as a metaphor for the necessity of risk-taking amid the general indifference and banality of ordinary life. Debombourg finds in the heroic scale of Mannerist male nudes a metaphor for societal, and especially male, violence as seen in popular super-heroes, an aggression and familiarity that he sees as echoed in the way staples are driven into board and their utter ubiquity.” (https://apps.carleton.edu/kettering/goedde/) While Žilda and Debombourg’s Goltzius-inspired works are not prints, a third artist, David Avery, created a set of four etchings that stays closer to Goltzius’ scale and compositions in their inclusion of the text around the circumference of each. But Avery has changed the characters in order to comment about issues facing us today. Safe, Clean, Cheap: Phaeton in the 21st Century, 2011, highlights issues of the environment and its imminent destruction at our hands. Too Close to the Sun, 2013, points at human’s problematic fascination with phones and screens. Running on Empty, 2016, critiques America’s dependence on big oil. And the last in the set, Mendacia Ridicula, 2018 (Latin for ridiculous lying), satirizes politicians and the divisiveness that has come from all that lying. I appreciate it when artists look to historical examples. It reinforces the idea that they know upon whose shoulders they stand. Wouldn’t it be cool to pull together a group of contemporary works with Goltzius’ engravings for an exhibition about inspiration and artistic heroes? I’m sure there are more examples of artists looking at The Disgracers. Let me know who comes to mind. There is deep richness to be found in the history of prints. Lucky for us, there are plenty of places to see prints like these and many curators and scholars who are happy to talk about them.

1 Comment

Hugh Pawsey

9/14/2021 05:16:01 pm

The Russian icon of The Transfiguration (e.g. by Theophan Grec) shows three disciples downhill from the main event. The text implies they've lost their senses making silly suggestions, but in the composition they're *boulversé;* traditionally one is preaching, one praying, one repentant, and all three knocked sideways, in free fall.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed