Ann Shafer As a curator and self-described print evangelist, I’ve always found printmaking is a tough sell to non-print people. It requires such a steep learning curve in knowledge, but once people are over the peak, usually they are in. At the museum, I spent a lot of time explaining techniques, like the differences between how etched and engraved lines appear. I didn’t mind repeating my spiel (hence the print-evangelist moniker), but the truth is, it just takes a lot of looking. Easy to do when you can box surf in the vault, not so easy if you only look at prints occasionally.

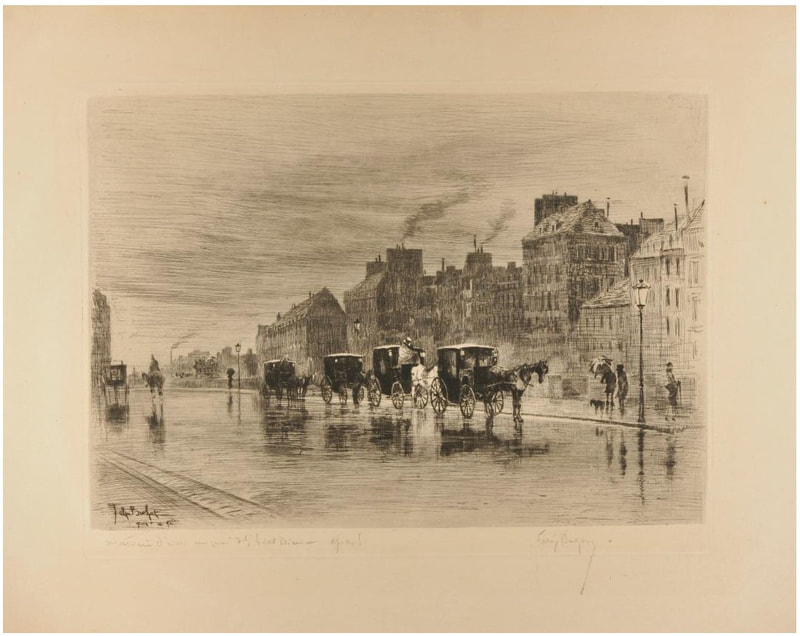

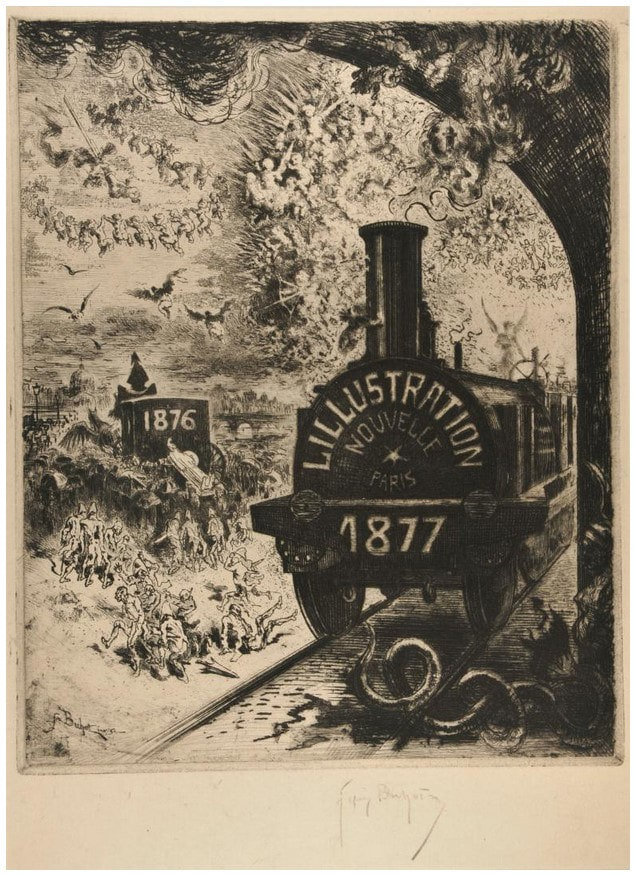

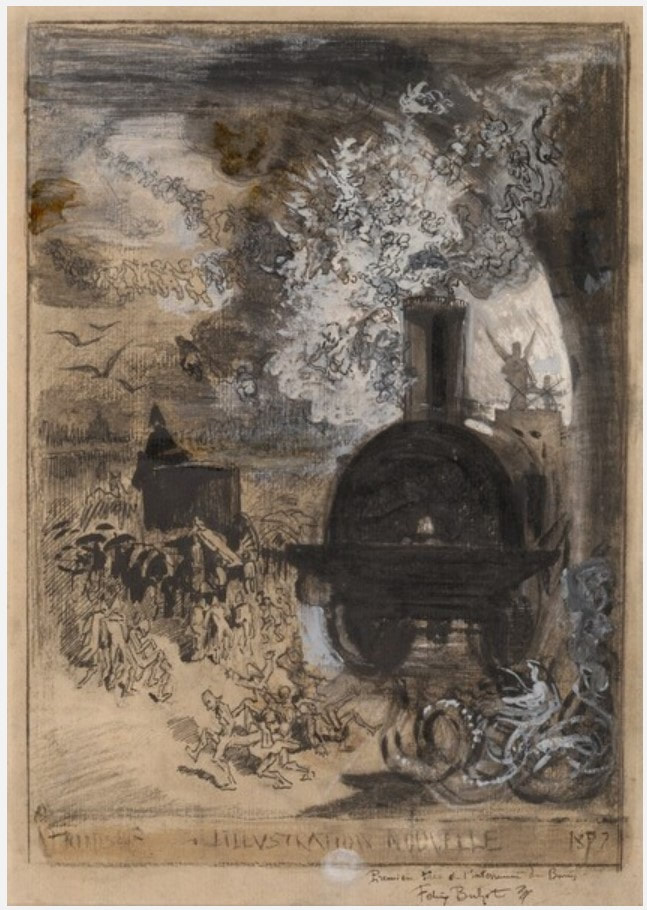

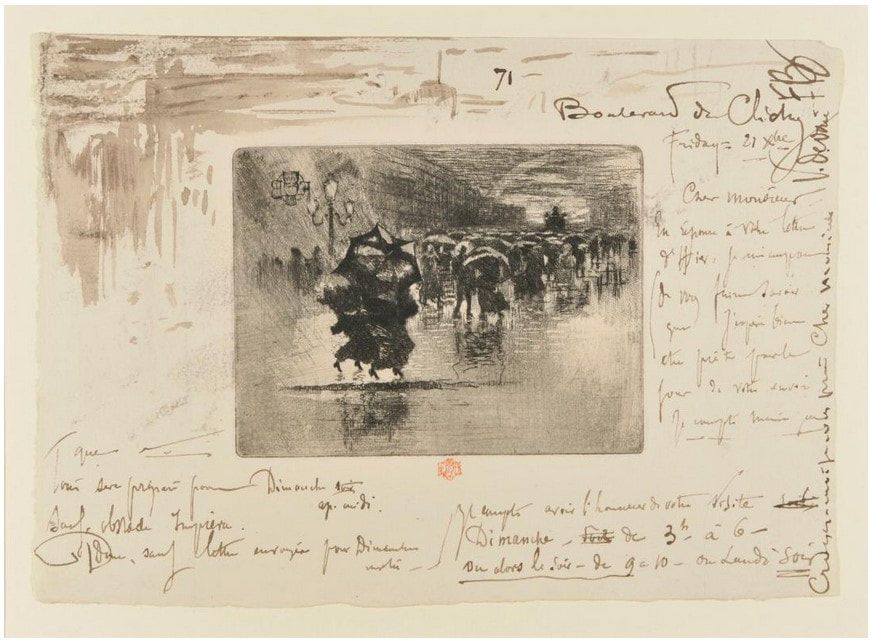

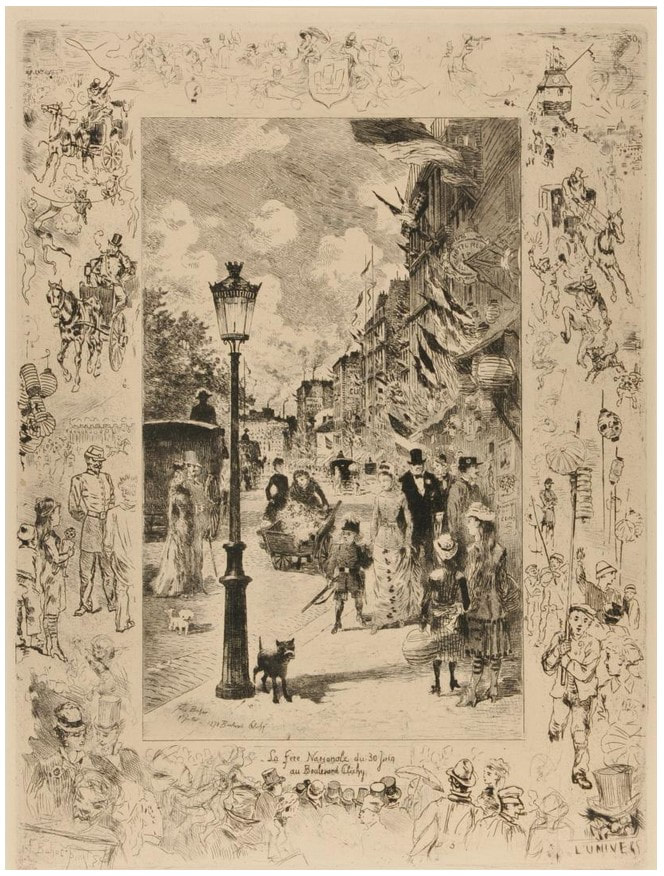

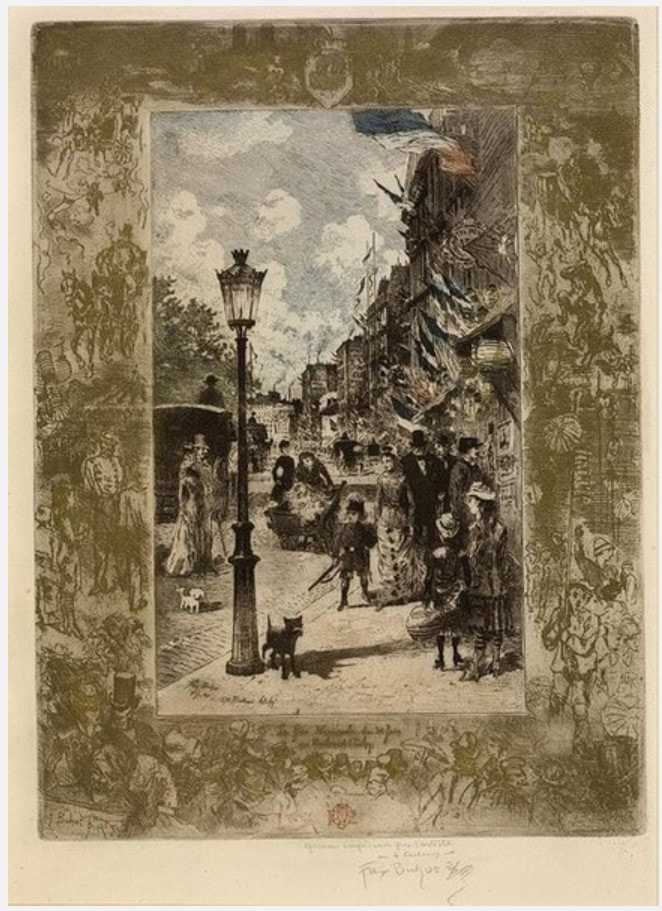

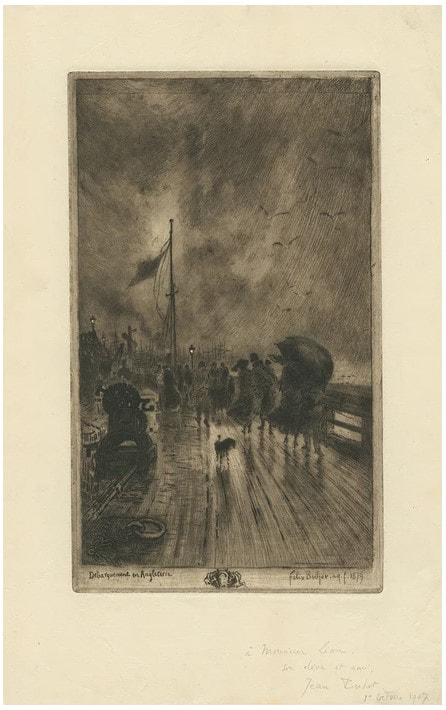

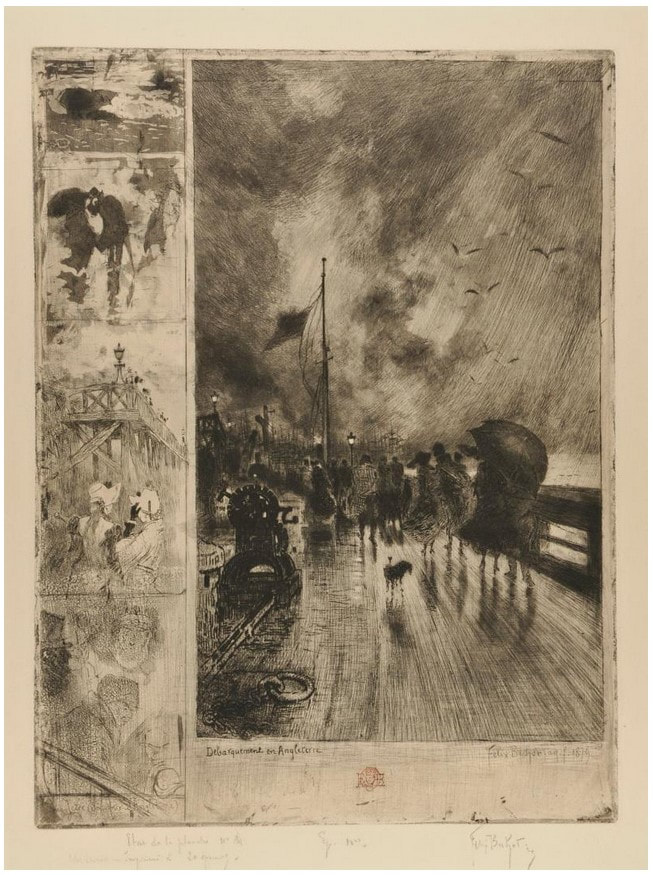

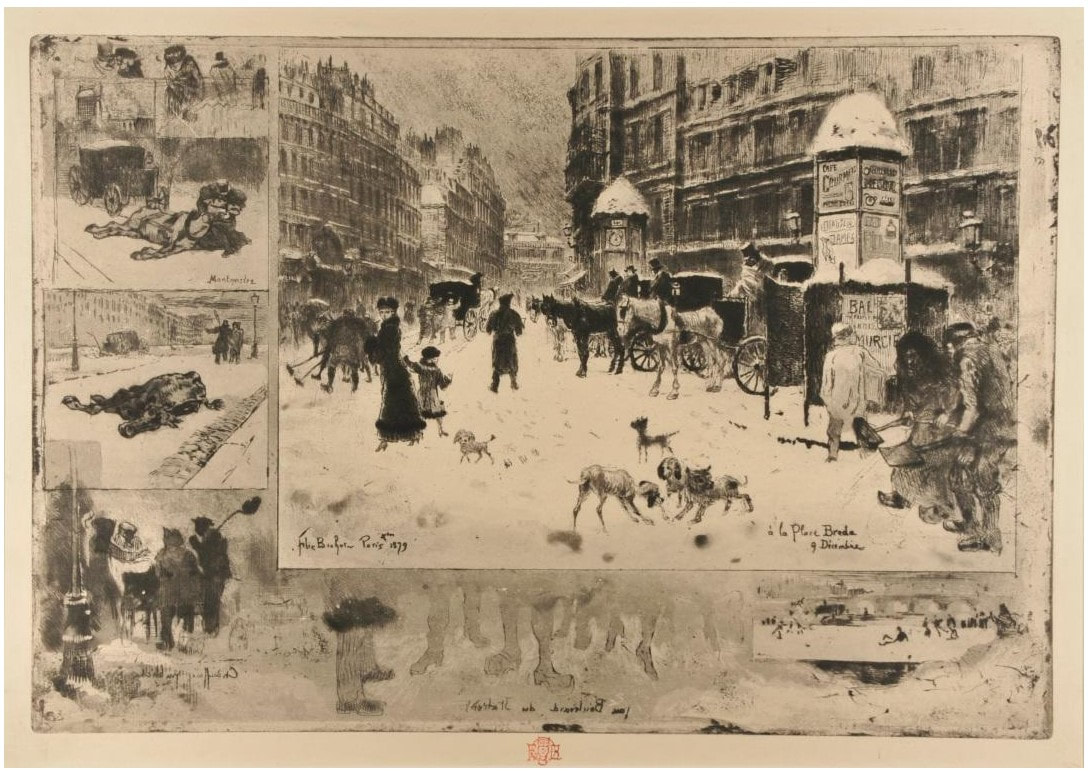

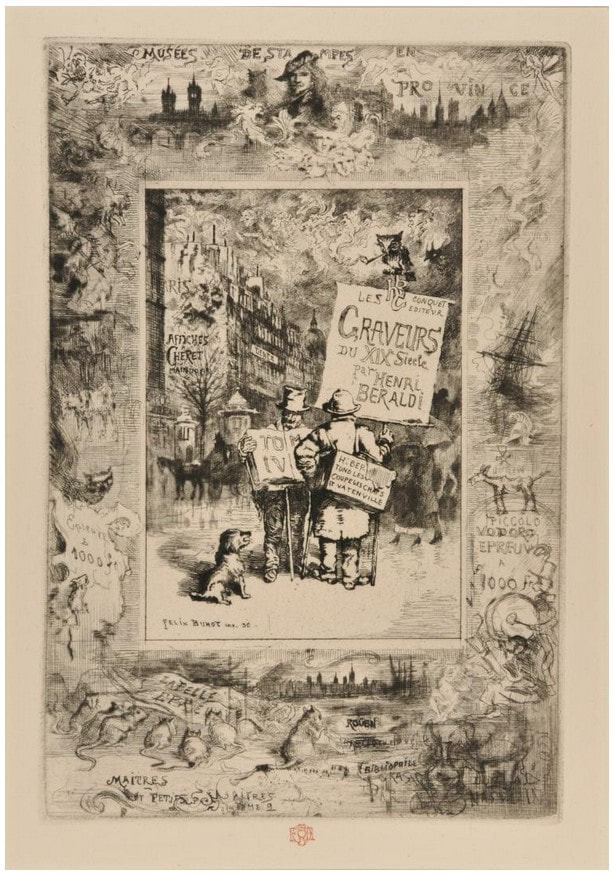

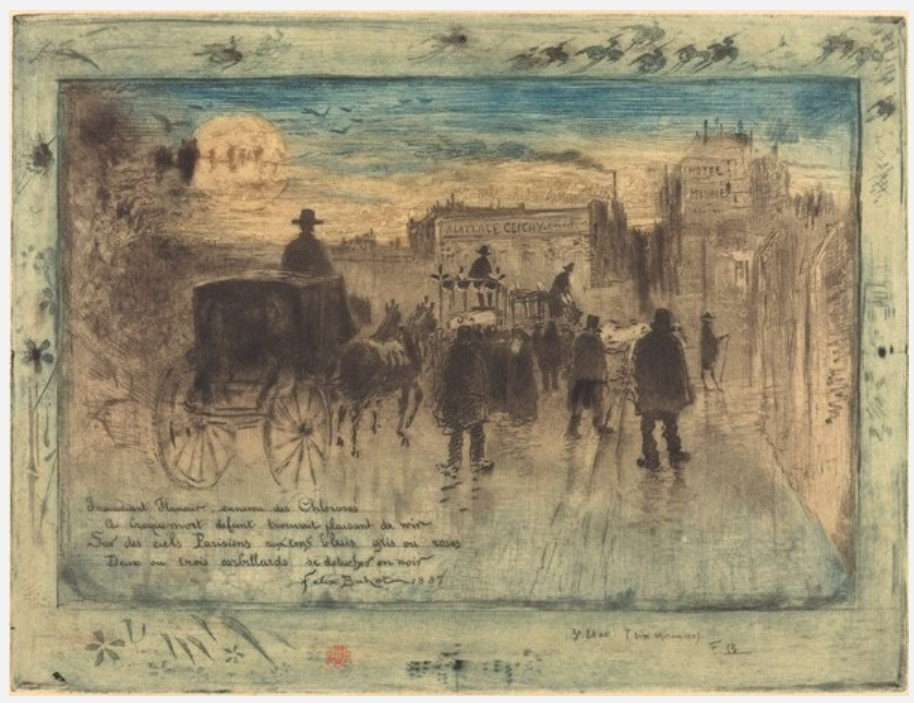

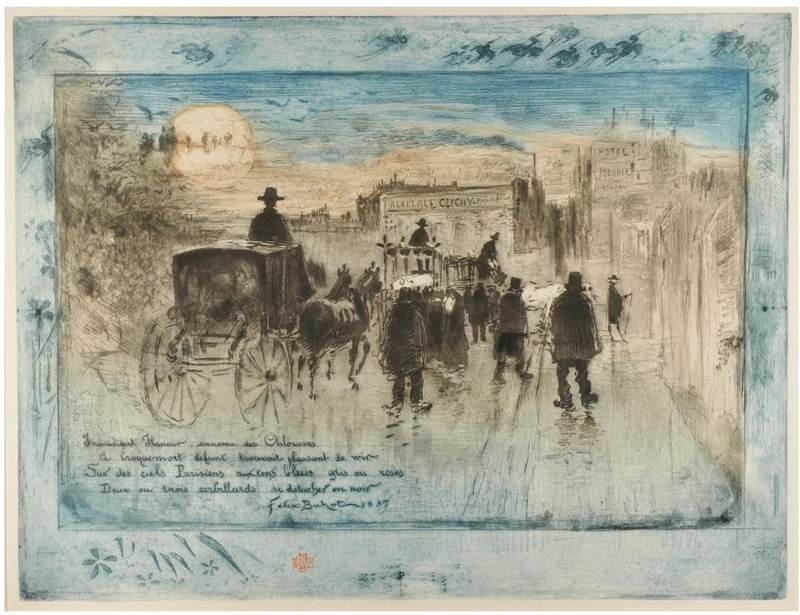

To help our audience really learn how to feel confident looking at prints, I always thought we should offer a printmaking 101 course—but such a thing would be impossible given time and resources. In my mind the solution was to mount exhibitions featuring each technique’s greatest hits as well as works by unsung heroes. Since I have a serious soft spot for intaglio techniques (etching, engraving, softground, aquatint, etc), I would start the exhibition series there. (Perhaps starting with relief makes more sense historically, but hey, these are my fantasy shows.) Stars of the intaglio exhibition would be Rembrandt, Callot, Goya, Canaletto, Piranesi, Whistler, Meryon, Braquemond, Cassatt, Arms, Picasso, Kollwitz, Milton, and today’s subject, Félix-Hilaire Buhot, who made incredible etchings from 1873 to 1892. Buhot (pronounced in French as Boo-oh; in English sometimes as Boo-Ho) was born in Normandy and was, sadly, orphaned at age seven. Somehow, he made his way to Paris and made a living as a commercial artist. He began making prints in 1873, and only a year later was singled out by Philippe Burty, a prominent critic who admired Buhot’s belles épreuves (beautiful proofs). The etching revival of the 1860s was already underway when Burty put forward the idea of special proofs to denote rare, superbly inked impressions printed by the artist himself. Burty created a market for prints by promoting the idea of the limited edition (in which an artist sets a certain number of prints to be editioned, and no more), special proofs on colored papers, special stamps, and marginalia. Not coincidentally, central to the etching revival was the concept of the peintre-graveur (painter-etcher), as etching provided a means for a more autographic mark and an involvement with inking and printing, as opposed to the commercial lithography and reproductive engraving trades popular at the time. Buhot distinguished himself from other artists with his use of marges symphoniques (symphonic margins), also called marginalia or remarques. Margins outside of the main image area are filled with quirky doodles, sort of like notes in a sketchbook, which often offer a different take on the main subject. Buhot also experimented with inking and papers—some of my favorites include his use of an amazing blue ink. In fact, his experimentation meant that almost no etchings of the same image are like any of the other impressions. Hence the term painter-etcher. Buhot portrayed both ends of the daily life spectrum, from celebrations of national holidays in National Holiday on the Boulevard de Clichy, 1879, to the disastrous effects of winter later that same year in Winter in Paris. The beauty of the latter belies the action. In December 1879, Paris was in a deep freeze and suffering greatly. In his print, it takes us a minute to notice the dogs fighting over scraps in the foreground of the main image, as well as the frozen bodies of horses found along the left side. Buhot enjoyed popularity in his lifetime in France and in America. His prints were collected by two major American print collectors: Samuel P. Avery, whose collection is at the New York Public Library, and George A. Lucas, whose collection is at the Baltimore Museum of Art. In subsequent years, the National Gallery of Art has also assembled a substantial collection, including many drawings. I love Buhot’s compositions, use of aquatint, spontaneous-looking doodles in the margins, and painterly application of inks that enhance the portrayal of various weather effects. In the study room we would have called them scrumpy. No surprise, his prints were favorites with visiting students. I’m in. Are you?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed