Ann ShaferPutting on my print evangelist hat for a moment to tell you about a remarkable set of six state proofs and the final engraving by the incomparable James Siena, which I acquired for the museum back in 2012 during the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. The print fair was run by the print department and directed by one of its curators going back to 1990 (with deep support from the friends group, the Print, Drawing, and Photograph Society). It was held annually until 2000. When I took it on in 2012, it took place biennially and I ran it in 2012, 2015, and 2017 (that curious break between 2012 and 2015 was due to renovations in the museum’s galleries). The 2017 fair turned out to be the museum’s last for a variety of reasons. But please mark you calendars for a new print fair coming to Baltimore April 29-May, 2022. Yes, I am involved. Yes, it is a great joy to be doing it again. Yes, I’m over the moon. More details soon. For now, details are at www.baltimoreprintfair.com.

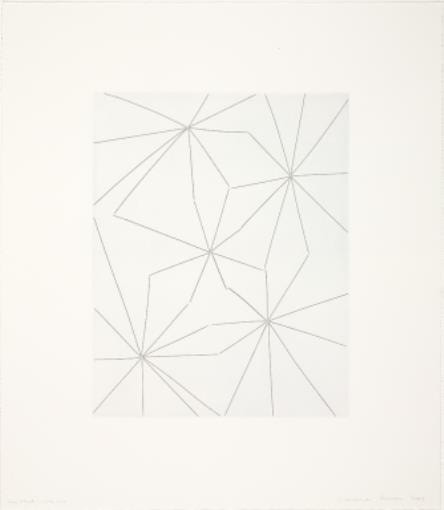

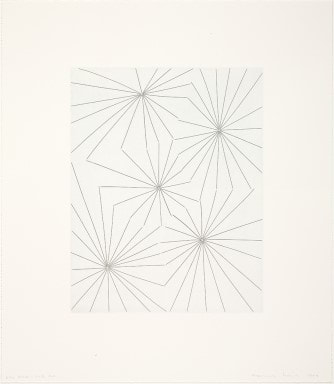

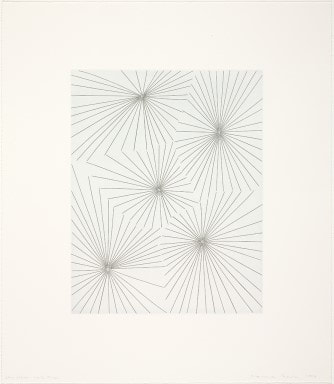

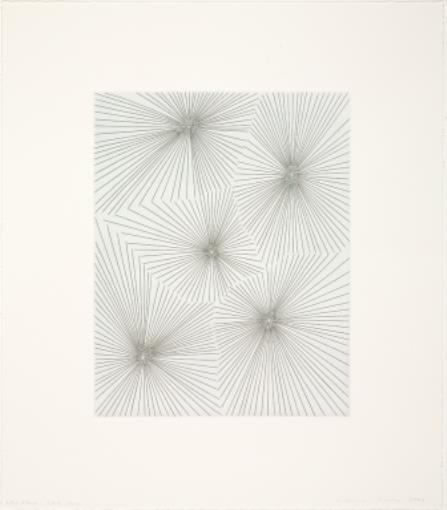

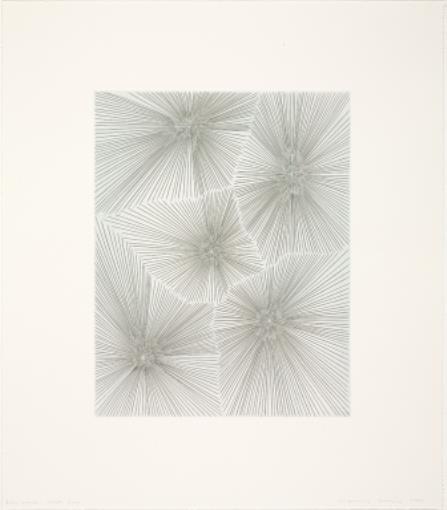

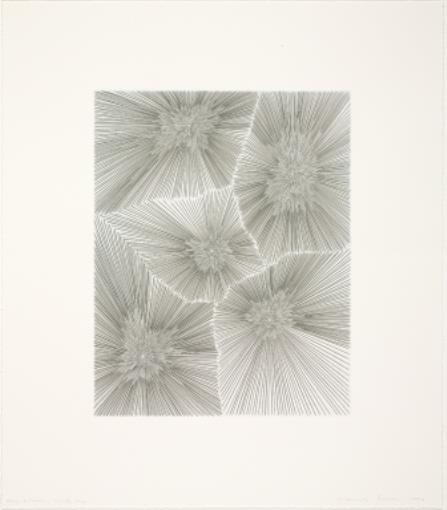

At the BMA’s fair, it was normal practice for the museum to acquire at least one print for the collection (the proceeds from the fair went directly into an acquisition fund). While there were fairs where nothing was acquired, in 2012, a set of seven engravings by James Siena caught the eye of the whole curatorial team. Printed by master prints Felix Harlan and Carol Weaver, all seven prints are of the same composition, but six of them are state proofs leading to the final print. It was a no-brainer. Who could resist these beauties all framed up and on the wall together? Not I. The opportunity to bring into the collection a progressive set of impressions was too delicious. State proofs are impressions taken from a plate in progress. When an artist begins to make marks, at a certain point—it’s random, usually when the artist feels compelled to see how the image is coming along—they will stop working on the plate, ink it up, and put it through the press. When they reach another good break point, they will print another impression to check progress. An artist can pull any number of progress proofs; there is no rule about how many should be printed. You can imagine that print curators love this kind of object because of its ability to show very clearly how the image was constructed. No Man’s Land was super helpful in the print room because we were always teaching visitors and classes about the ins and outs of printmaking. What better way to talk about the steps in printmaking than to show them physically? James Siena works mainly with abstraction, often with a set of parameters that are to be either followed or consciously ignored. Often the image fills the entire canvas or piece of paper, pushing all the way to the edges. Our eyes are drawn all the way to the edges where one finds a tension between the marks and that edge. It’s almost like the image wants to push outward past the confines of itself. In No Man’s Land, the five bursts of radiating lines push against the edges and each other, as well as explode inwardly. Although completely abstract, one can see what the title helps us understand. That this is an abstraction of an aerial view of a World War I battlefield. This allusion to reality is at odds with the elegance and precision of the engraved lines, their crisp coolness, their strength, and confident straightness. Zoom in and one notices that virtually none of the lines touch or cross each other. This increases the tension and the potential energy—they appear to be suspended in time, ready to collide at any moment. I love going all the way back to the first state when each burst consists of between eight and eleven lines and tracing the steps to finality. The central burst has eight lines radiating outward, and then in a clockwise pattern, they each have nine, ten, ten, and eleven lines respectively, following a sort of Fibonacci sequence in its pattern. At this point I see spiders more than anything else. In the second state, lines are doubled, and I start seeing spiders’ webs. Weird things happen when the density of the lines increases and decreases. Spiders’ webs become celestial beings along the way. And finally, the bomb blasts come into view. They are not just bursts with more and more lines. They are more complicated, and, for me, the journey is the reward. My experience of the image is so much richer having come through from state one to the final iteration. As we said often in the print room, these reward scrutiny.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed