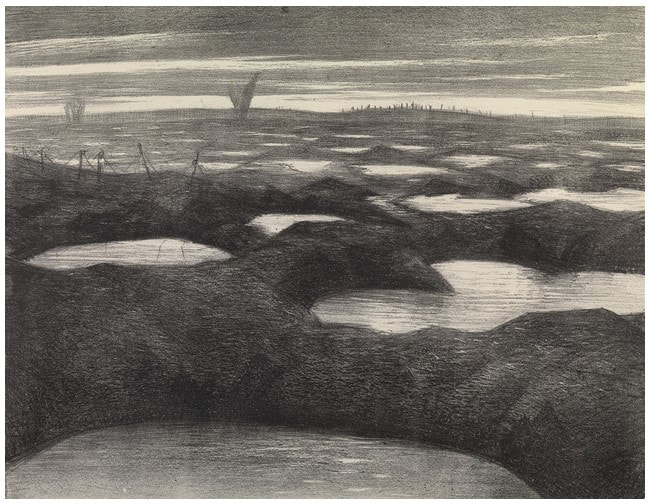

Ann Shafer November 11, 2020, is the 102nd anniversary of the end of World War I. It is known as Armistice Day in the US—generically now called Veterans’ Day—and in the UK it is called Remembrance Day. (Brits wear those red poppies pins to mark the day.) I believe remembering and knowing our shared history is critical. Ignorance too easily leads to repeating actions that could/should be avoided. World War I was a tremendously deadly conflict, and its devastation should never be forgotten. Exact numbers of the dead are not known—even though the war was the first in which soldiers were issued identification tags—but estimates range from 9 million to 22 million deaths, including both military and civilian. Marking days like this reminds us of how much we had to lose and how much we gained. And how fragile it all is.

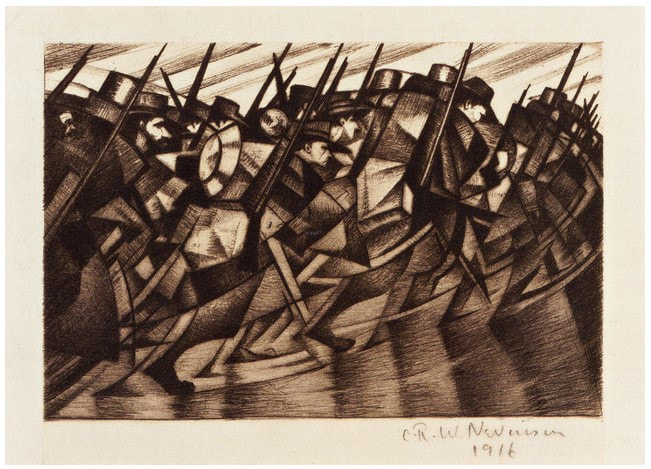

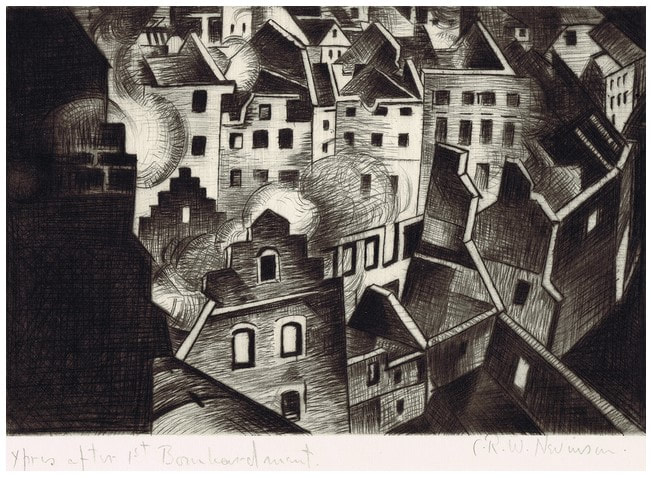

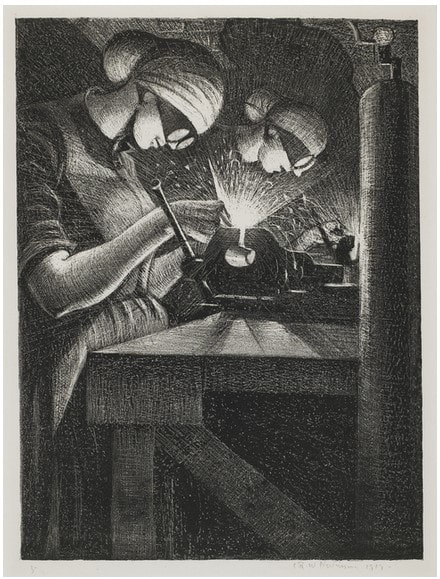

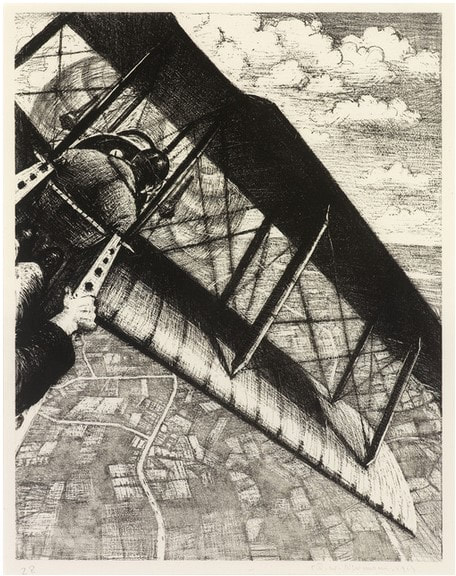

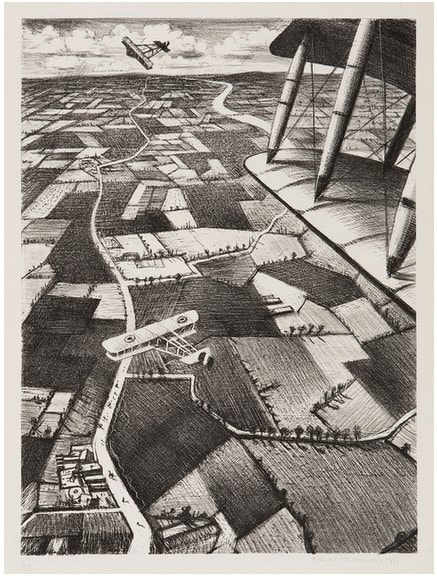

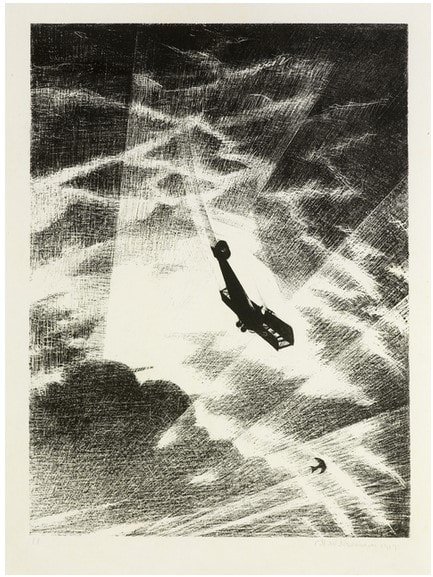

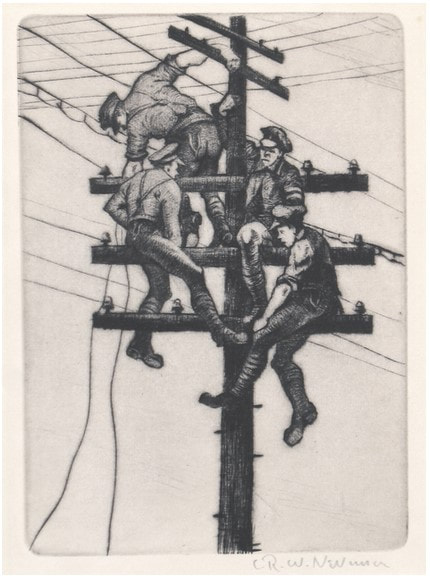

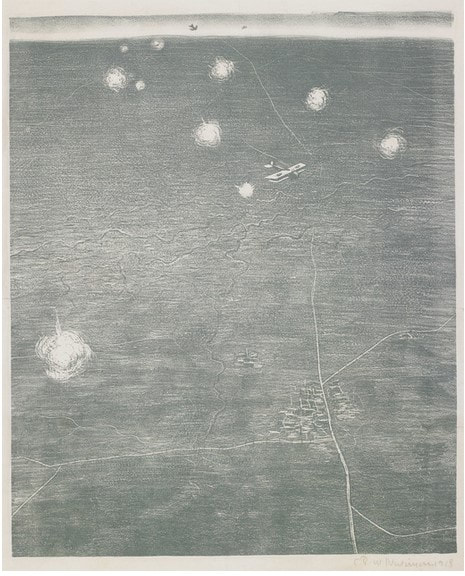

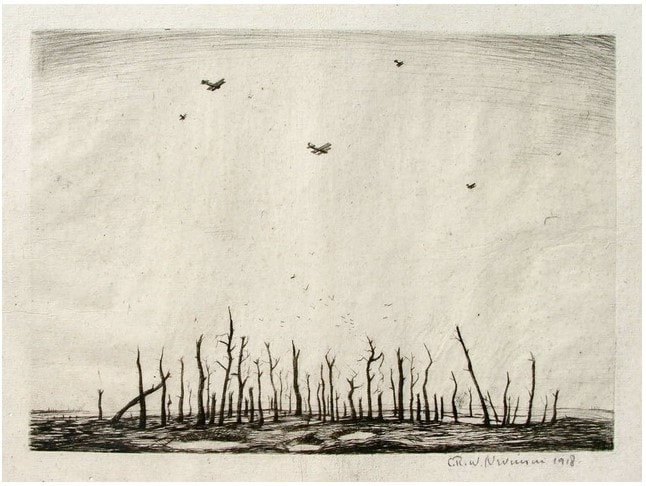

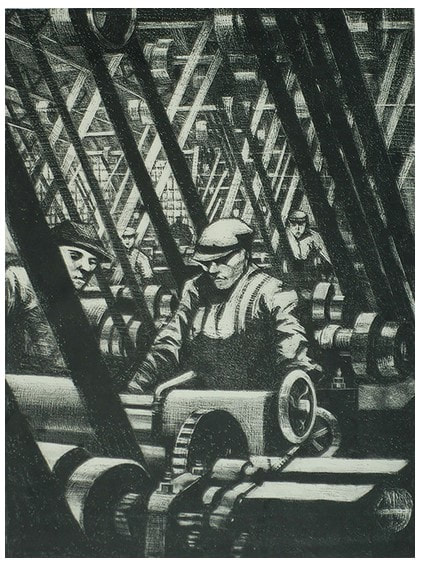

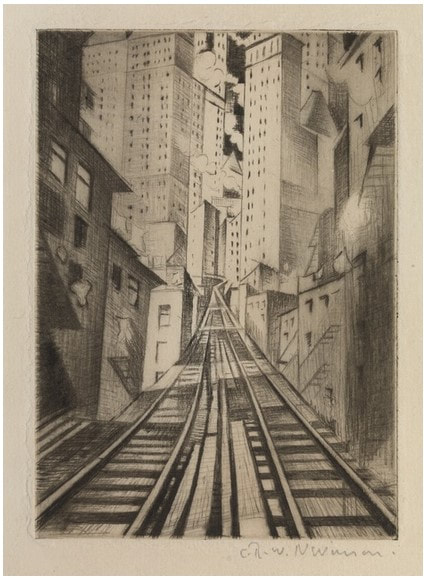

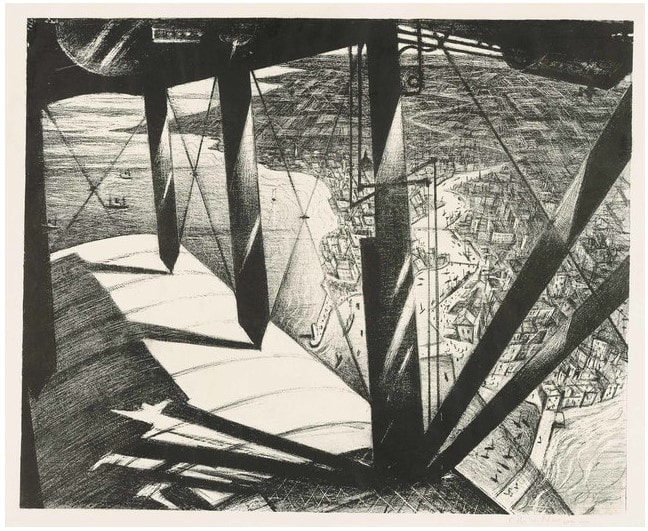

There are many artists on both sides who created work in response to the war, but I want to introduce you to British artist and World War I veteran, Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946), whose prints I always wanted to acquire for the museum. When you work in a vast collection of prints, one gets lulled into a sense of “we must have something by X artist.” It always surprised me to find the collection lacked anything or anyone. But the BMA’s collection has no prints by Nevinson, whose works from the war period I find to be stunning. Timing and inflated prices often prevent curators from filling gaps—it’s super frustrating. In my time at the museum several artists’ prints that were on our wish list had prohibitively high prices: Provincetown white-line woodcuts by Blanche Lazell, early American modernist etchings by Edward Hopper, color linoleum cuts by the Grosvenor School, color prints by Mary Cassatt, etchings by master-of-urban-scenes Martin Lewis. The same is true about prints by Nevinson; his prices were out of range for our acquisition budget. Ah well. Let me show you why his prints are on my list. Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson, sometimes recorded as C.R.W. Nevinson and called Richard, was an artist who made his mark with scenes of World War I, a conflict in which he took part. He spent the beginning of the war in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit tending wounded French and English soldiers. He was appointed an official war artist in 1917. In addition to prints, he also created paintings. Artistically, Nevinson’s early friendship with the founder of Italian Futurism, Filippo Tomasso Emilio Marinetti, had an immense influence on the former’s style, particularly in its machine-age aesthetic. He also befriended, and then had a falling out with, radical writer and artist Wyndham Lewis who formed the Vorticists group. Nevinson, whose sensibility was a natural fit for the Vorticists, was banned from the group. No matter. After making some remarkably modernist, powerful, and beautiful prints, eventually Nevinson decided that mode of image making wasn’t adequate to convey the horrors of war and he began to create imagery in a more realist manner. It’s always curious when an artist’s stylistic trajectory seems to travel backward but take a look at these prints from the ’teens and judge for yourself.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ann's art blogA small corner of the interwebs to share thoughts on objects I acquired for the Baltimore Museum of Art's collection, research I've done on Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17, experiments in intaglio printmaking, and the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed