|

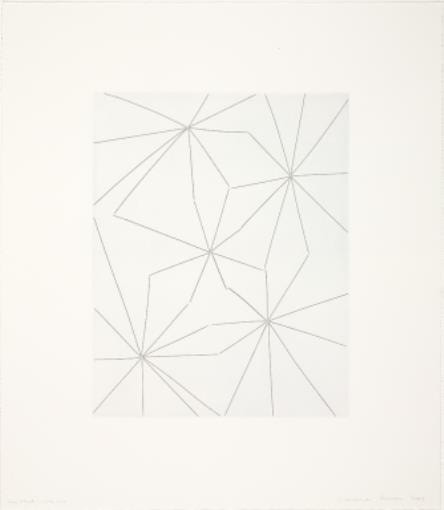

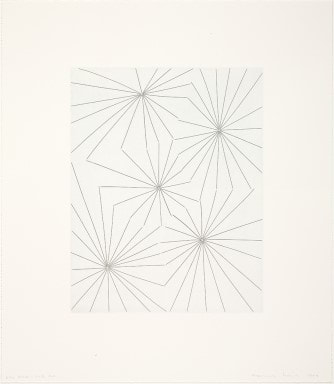

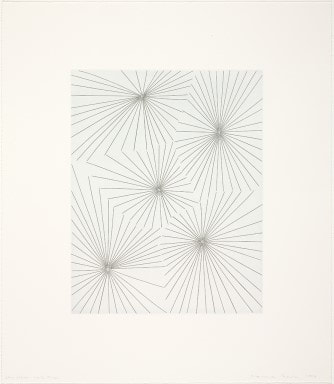

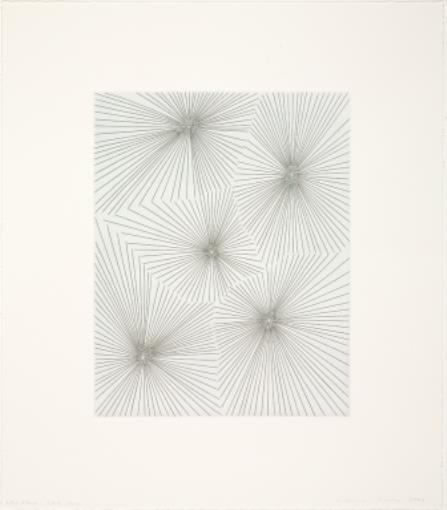

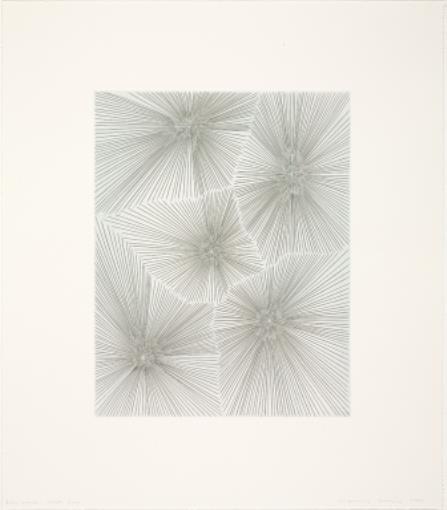

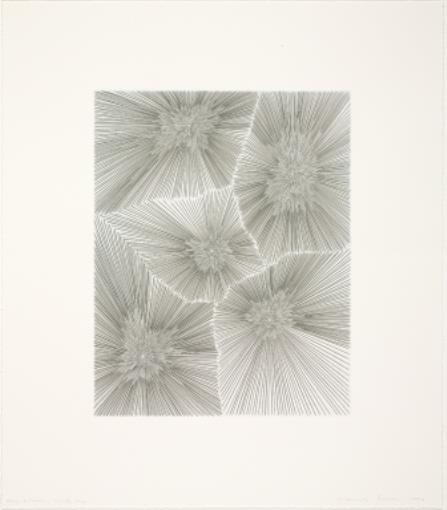

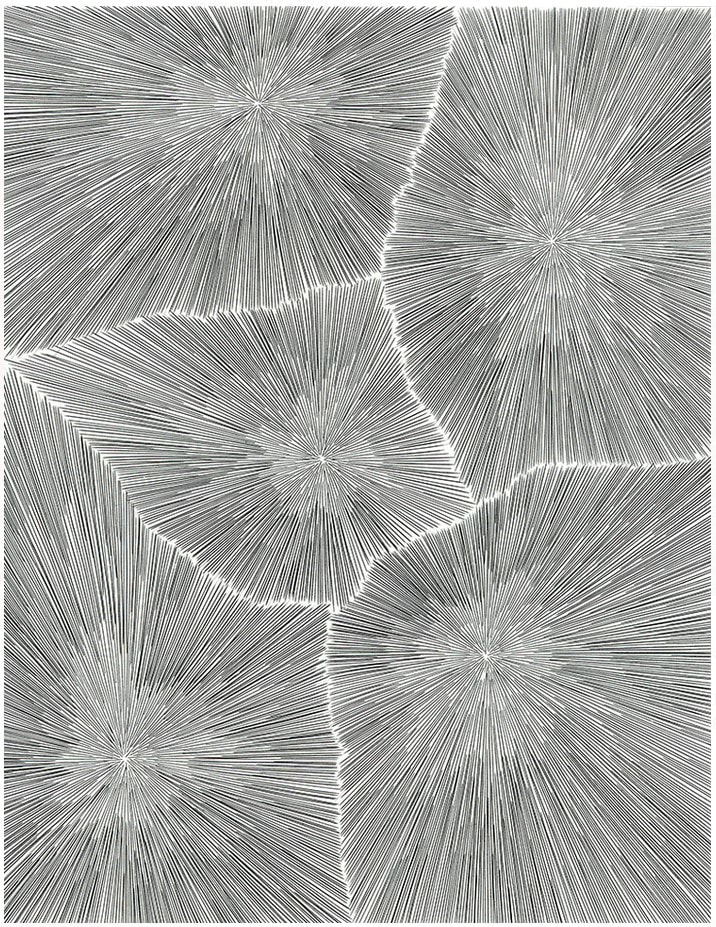

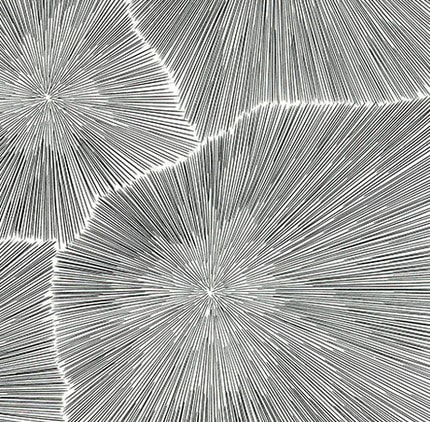

Curator Ann Shafer revisits the set of six progress proofs and the final engraving of No Man's Land, 2004, by James Siena. You can imagine that print curators love this kind of object because of its ability to show very clearly how the image was constructed.

Also, there is a video of an interview I conducted with James Siena available here. Images: each image's credit appears in the photo caption Music: Michael Diamond

0 Comments

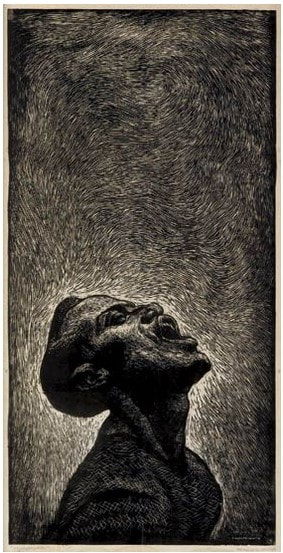

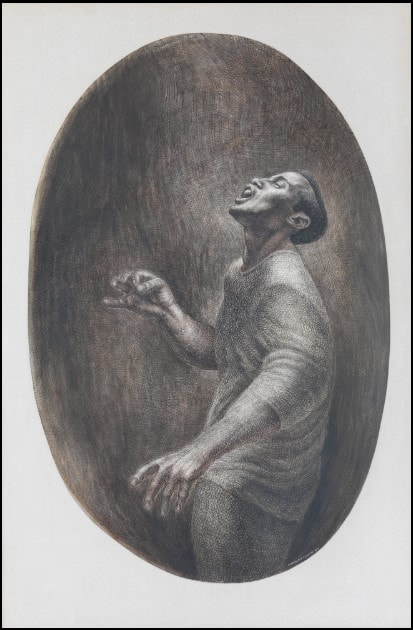

In episode 6, I revisit the linoleum cut Voice of Jericho by Charles White (there is a blog entry about it elsewhere on the blog page). I wanted to look at it again because it remains on my top-5 list of objects from the BMA's collection that I would love to have for my own collection.

The video version of the episode is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7OHtCCYM4oU A link to Harry Belafonte's television special is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otw0FtXjOKc&t=507s. Bald Headed Woman is the first song Belafonte performs, but doesn’t begin until the 4:40 mark. Images: each image's credit appears in the photo caption Music: Michael Diamond

I'm one lucky person. I love what I do—the curatorial part. But I also have a love for the doing of art. I loved art class in school, loved teaching third and forth graders about artists and doing a related project at my sons’ school, I loved and still love doing stuff with my hands. These days that is mostly writing. But listeners of Platemark will already know that there was a fateful moment in college when I decided between studio art and art history. Really it came down to the fact that while I love doing and being around creatives, I do not have that drive to create something every day. And that was the watermark for me. Dabbling in graphic design has fulfilled that low-level need to create in adulthood. But I have long wanted to start a print shop and print publishing studio. Need to win the lottery to enact that plan, so it is on the way back burner.

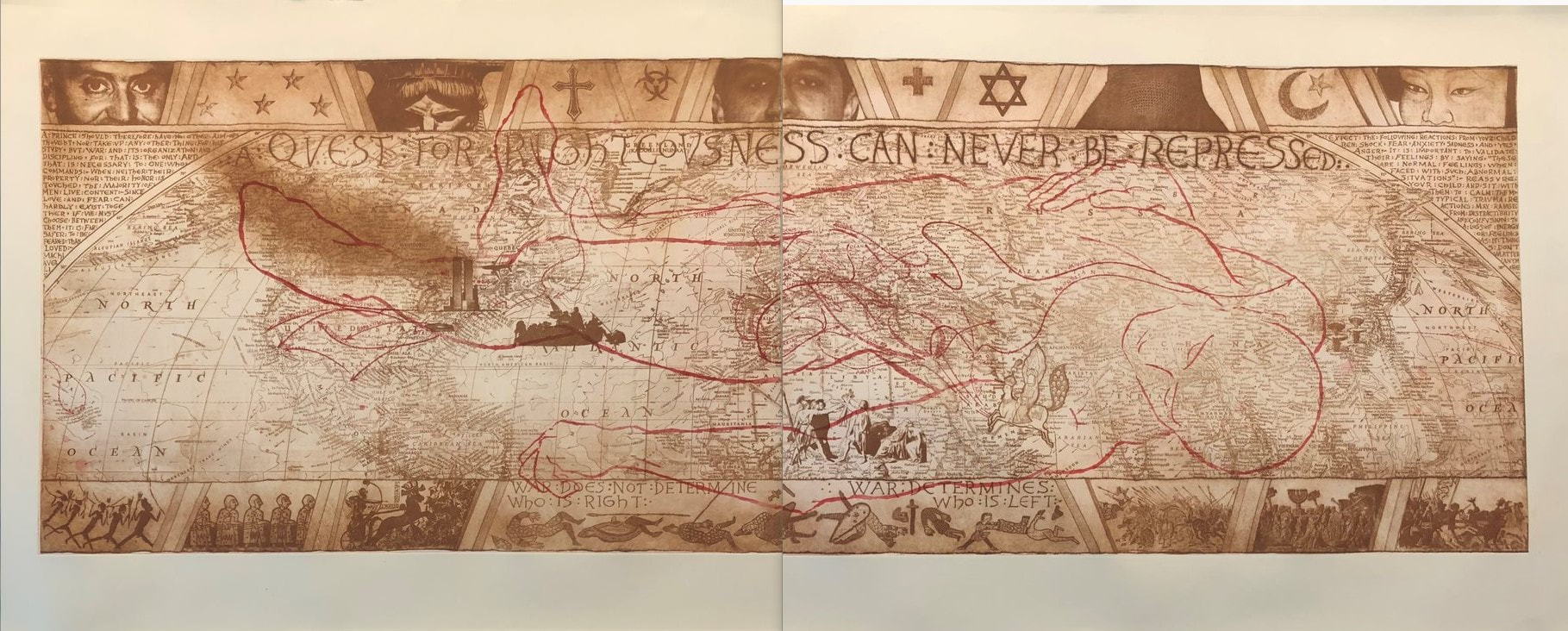

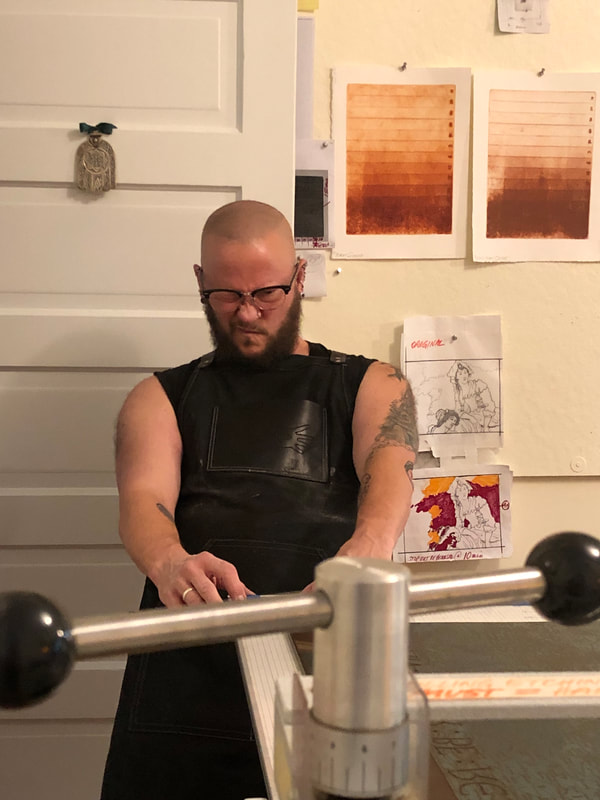

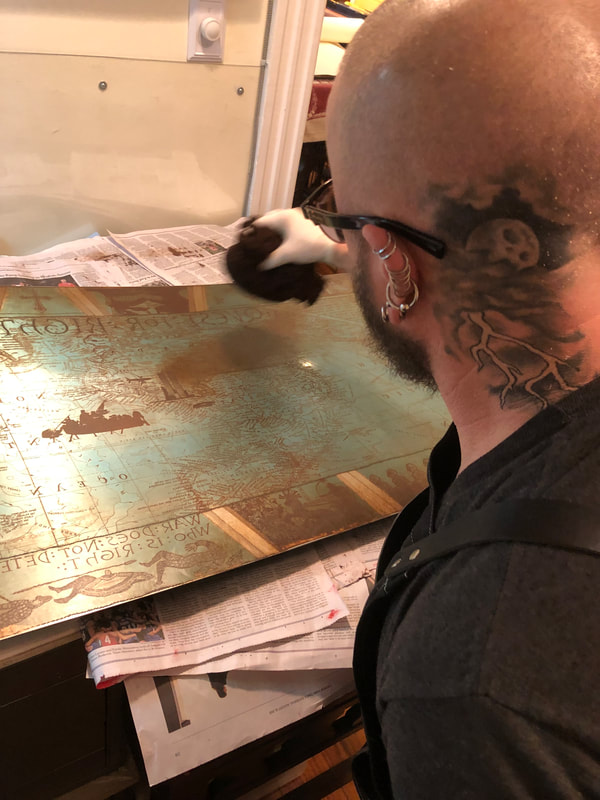

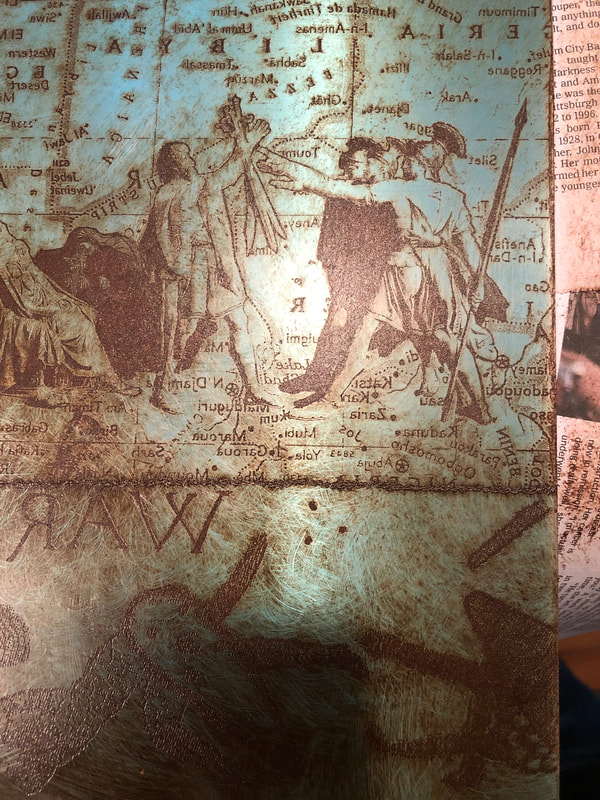

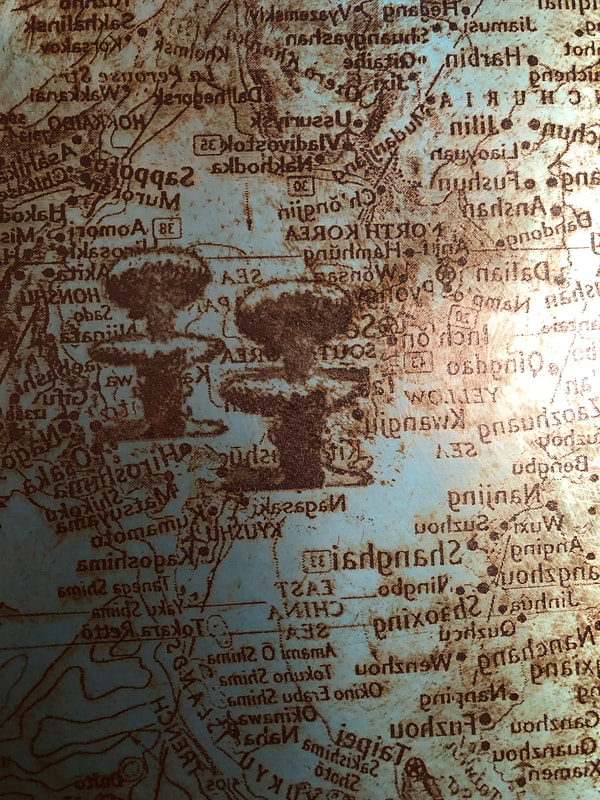

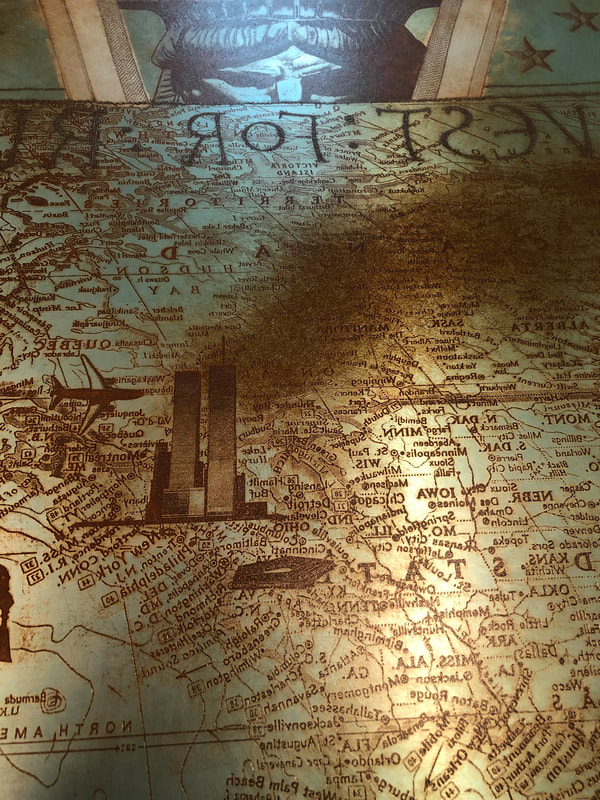

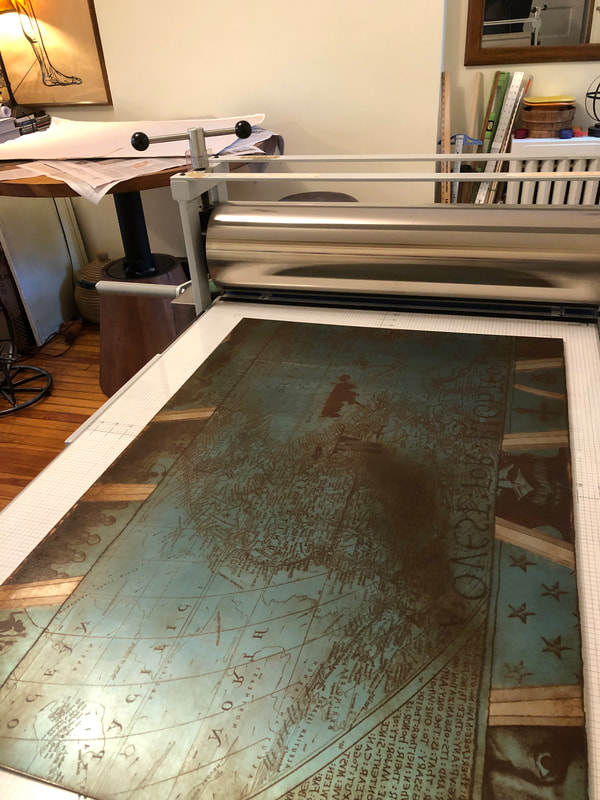

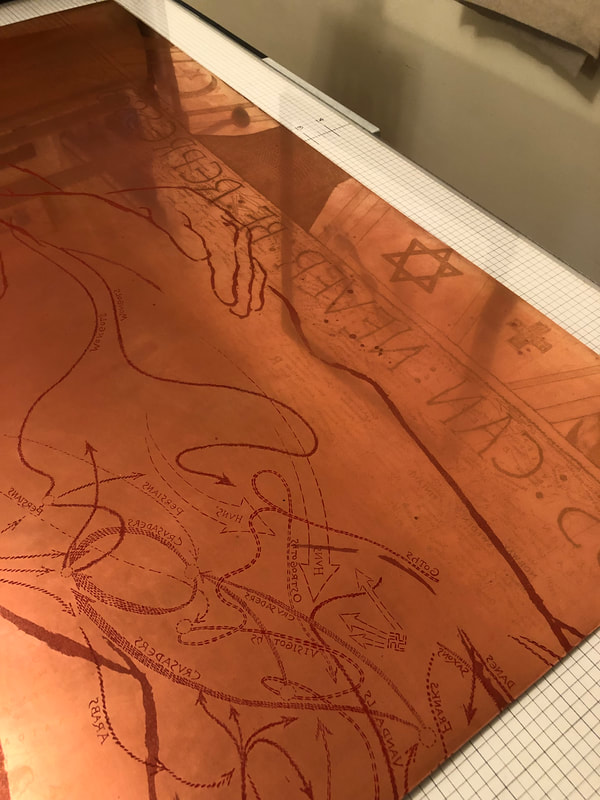

When I started in the print department at the BMA, I was the person who hosted classes. There are many wonderful professors who I have met this way, and it was always a joy to see students’ eyes light up in front of a Rembrandt etching or a Hayter engraving. I never expected to become close friends with any of them, until I met Tru Ludwig, who is one of the rare art historians who is also an artist. That combination is special because those people can not only tell you about the background history of the artist and the subject matter, but also how it was done with such a depth of knowledge it is breathtaking. Back in 2005, Tru was teaching History of Prints at the Maryland Institute College of Art, the renowned art school in Baltimore, MD. Tru brought these art students to the BMA to teach the history of prints from the objects themselves. At first, they came for just a few sessions, but by the time we were in full swing, they came to the BMA’s print room six times and looked at hundreds of prints from Durer to yesterday. It was a lot of work, pulling and putting away that many prints, but it was always worth it. Tru is a gifted orator who infuses his speech with sound effects and colloquialisms. Just enough to keep any sleepy college art student engaged. There were always moments in the frantic shuffling of prints and interleaving that I just stopped to listen to Tru go on about Rembrandt's Three Crosses, Max Klinger’s Die Handschuh, Kathe Kollwitz’s Battlefield, Leonard Baskin’s Hydrogen Man, and Peter Milton’s Hotel Paradise Café. Every time through the class, some 18 times, Tru would get me with goosebumps or tears welling at the tale he wove about how art is central to our existence. Since I am no longer at the BMA, and Tru is no longer teaching History of Prints, I convinced him to join me in creating a podcast of the history of prints class. Platemark series two is underway—we have just gotten through Durer. It may seem counterintuitive to talk about visual art in an audio format, but the images are available in each episode’s show notes. I encourage you to check it out. Meanwhile, I have been apprenticing at Tru’s print studio, The Purple Crayon Press. Earlier this year I helped wipe and print two large etchings, Ask Not and Dumb Luck, for the first time. I mean I have watched the process many times, but this time I was aproned up and had gloves on and got dirty. What you may not know if that if you are a curator of prints, you do not ever have had to make any. It is not a requirement. But I can say, it certainly helps to understand just how finicky the process can be. Recently I spent two days helping Tru pull a magnificent etching, one whose edition had never been completed. I can surely see why. We accomplished printing three impressions over two days. It is a large print called TapHistory, 2005, and consists of two large sheets that are joined in the center. Each half is two plates. One in brown and one in red. So, that basically means we printed six two-plate etchings, or the equivalent of twelve one-plate prints. It’s a lot. And so rewarding when it all comes together, and you get the quality of impression that you are after. TapHistory is a play on the format of the Bayeux Tapestry, a really important embroidered length of fabric that tells the tale of the lead-up to and the Battle of Hastings in 1066, when William, Duke of Normandy defeated the British upstart Harold, Earl of Wessex, following the death of King Edward the Confessor. It is thought that the outcome changed England, its language, architecture, and way of life for the future in massive ways. The tapestry was created only a handful of years after the battle and offers vignettes that tell us about military strategy, armor, cooking conventions, fashion, and all sorts of stuff. It is some 230 feet long and 20 feet tall. The main action takes place along the center, while a top and bottom border carries other figures and stories, which sometimes are fables or cautionary snippets that forecast the future. Tru’s print mimics that format. There is central action and a top and bottom border carrying other supporting information. In the central section is a map of the world, the kind you might find from National Geographic. Noted in tiny red stitches (mimicking the tapestry) forming arrows are paths of conquest by various peoples across time: Goths, Visigoths, Vikings, Mongols, etc. It is also includes art historical quotations. That is Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii in the lower center, which depicts three sons and their father issuing an oath that will result in only one son surviving an upcoming land-dispute battle. In the left center is Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (in reverse). Over in Japan, two mushroom clouds rise about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And just above Washington are the Twin Towers—one is streaming smoke and the other is about to be hit with an airplane. Remember, Tru made this shortly after 9/11. To the right of the Oath of the Horatii is Muhammad Borne Aloft by the Buraq, from a Turkish version of The Progress of the Prophet, 16 century. The text running across the top of the central panel is “a quest for righteousness can never be repressed,” which is a quotation from Nelson Mandela, 2001. In that triangular space at the left edge are quotations from Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince, 1532. Opposite, in the right-hand triangular space are excerpts from Baltimore County Public Schools letter sent to families following September 11, 2001 (Tru’s son was in a Baltimore County school at that point). Overlaying the brown map in the central panel is the red outline (a chalk outline if you will) of the dead toreador figure from Edouard Manet’s painting at the National Gallery of Art. Across the top are partial faces of note: from left to right: Brian Sweeney, one of the pilots who died on Flight 175, which crashed into the south tower on 9/11; the angry eyes of the Statue of Liberty; Mohammed Atta, the alleged pilot of Flight 11, which crashed into the north tower on 9/11; Sharbat Gula in a full burka—she was the young woman with starkly green eyes who was photographed by Stephen McCurry in 1984 and on the cover of National Geographic the following year; Ogedei Khan, son of Mongol warlord Genghis Khan. Along the bottom are small packs of warriors heading into battle from various periods of history, along with the Chinese proverb “War does not determine who is right. War determines who is left.” I have often suggested to artists to reduce the number of elements in a work, thinking that if one thing says it well, you do not need five things. When I look at Tru’s print, I see cacophony, but also a deeply felt commitment to making the point: why are we doing this and why do we keep repeating history? The number of elements that all point at that point is many. But then that is the point, isn’t it? There are so many examples of conquest, war, and tragic deaths that have and continue to occur. It is maddening. I continue to be deeply impressed by Tru and his work. Well, more than impressed. Astonished. Listen to the episode by clicking the player below. Or, head over to YouTube to watch the video version. Images © Ann Shafer and Tru Ludwig Music: Michael Diamond

Some process shots from our printing sessions, October 18-19, 2021, Purple Crayon Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

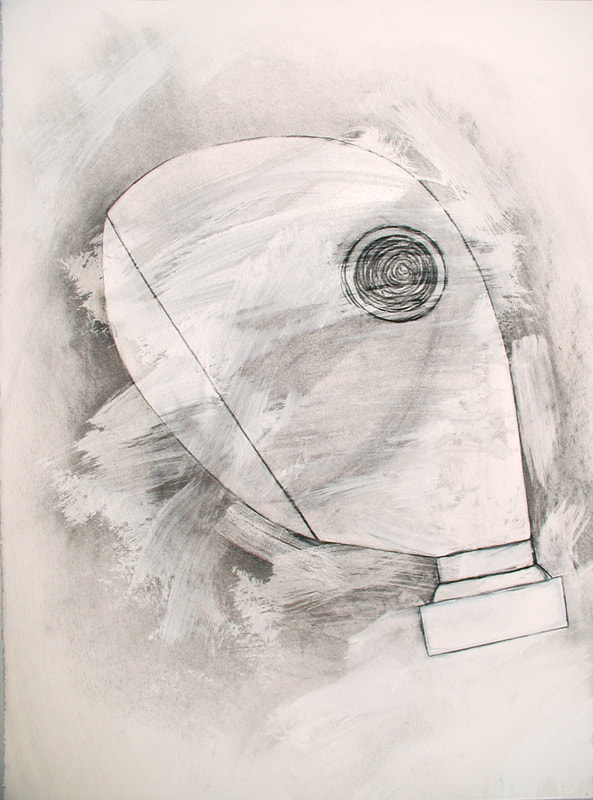

Episode 4 focuses on three drawings by William Dutterer, which she brought into the collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2015.

For some reason, the anniversary of 9/11 struck harder than other years. The idea of an anniversary is an artificial construct. I mean, twenty years, some 7305 days, there’s nothing concrete about it. So why did the twentieth strike so hard? Over the years, I acquired works of art for the museum’s collection that were pointed in tone, tackling either political, social, or some other tough topic. I kind of became known for my interest in difficult art. I believe that art can present ideas that cause people to think harder about stuff, and that artists are society’s court jester, the character at a royal court who was part comic part critic, and was just about the only person who could tell the king or queen what was what. Artists hold a unique position in society. High stakes, culturally influential, etc. In 2015, I secured a gift from the estate of the artist William Dutterer. The three drawings were part of a group of works featuring simplified cartoon-like heads that were wrapped, blind folded, or gagged. Dutterer was already working in this mode when he watched the second tower fall from the roof of his SoHo loft on 9/9/2001. They take on even more urgency seen through that lens, and twenty years later their significance is still potent. Dutterer’s oeuvre includes other themes, but the heads are my favorite. Well, I do love the Joe Diver paintings. I tell people a lot that works swim around in my head, and these are no different. During the last year I have been working with Catalyst Contemporary, a gallery in Baltimore. When the gallery’s curator, Liz Faust, and I were brainstorming about upcoming shows, Dutterer popped into my head. Gallery owner Brian Miller reached out to Jamie Johnson, who was married to Dutterer until his death in 2007, and who manages his estate, and plans were formed to exhibit Dutterer’s work at Catalyst Contemporary. That exhibition, A Lie Not a Wish, opened appropriately on 9/11. It is open until October 9, 2021. The exhibition is focused on the heads and axes, which are related to the works Johnson donated to the BMA. It all comes full circle. Images: copyright The William S. Dutterer Trust Music: Michael Diamond

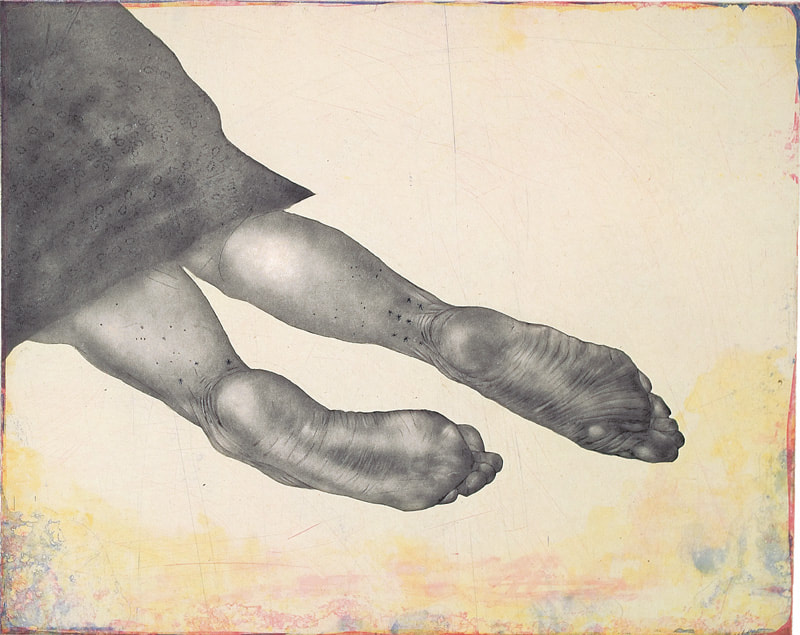

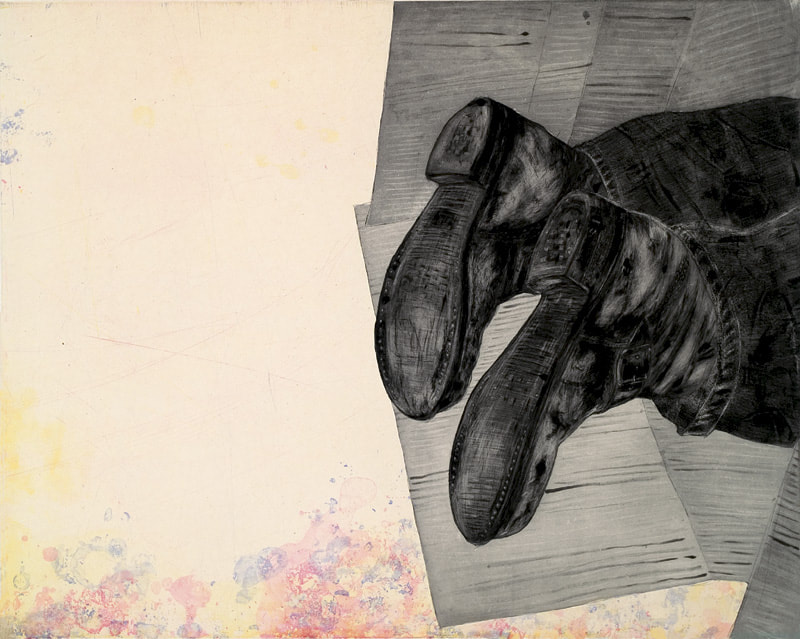

Episode 3 has Ann looking at a set of two four-plate etchings by the Kiki Smith, which she made at Crown Point Press in San Francisco. Home and Still, 2006, are haunting images of feet. It becomes clear quickly that these are the feet of homeless people lying on a sidewalk. Still features the lower legs of a bare-legged woman, lying on a concrete sidewalk. She has tiny star tattoos on the back of her ankles. These are the artist’s legs, by the way. Home shows the lower legs of a man in boots, who appears to be partially sheltered in a cardboard box. Smith came up with these evocative images while wandering around San Francisco, which has more than its share of homeless people. They are stark and powerful images that remain embedded in Ann's mind.

The audio link is below. You can also find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, etc. The video version of this episode is on YouTube. Publisher: Crown Point Press Collaborative printer: Emily York Images: ©Kiki Smith and Crown Point Press Image credit: Crown Point Press Music: Michael Diamond

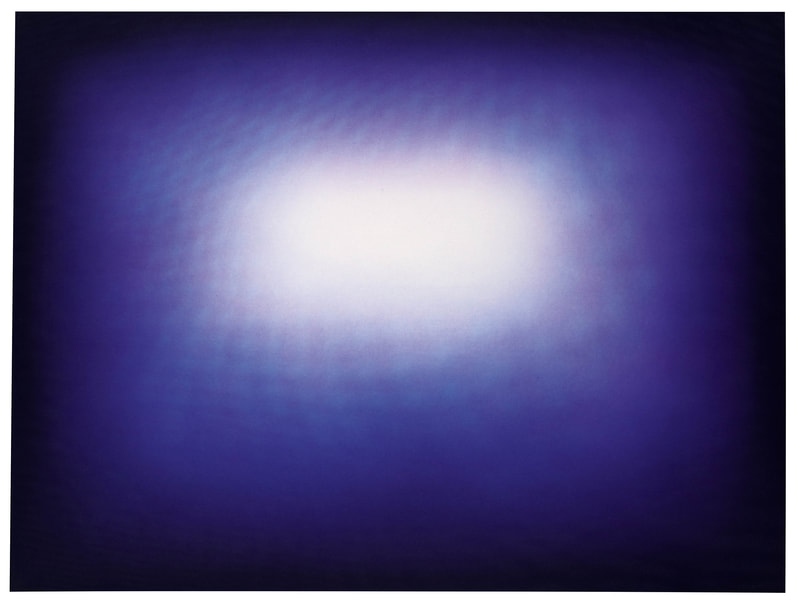

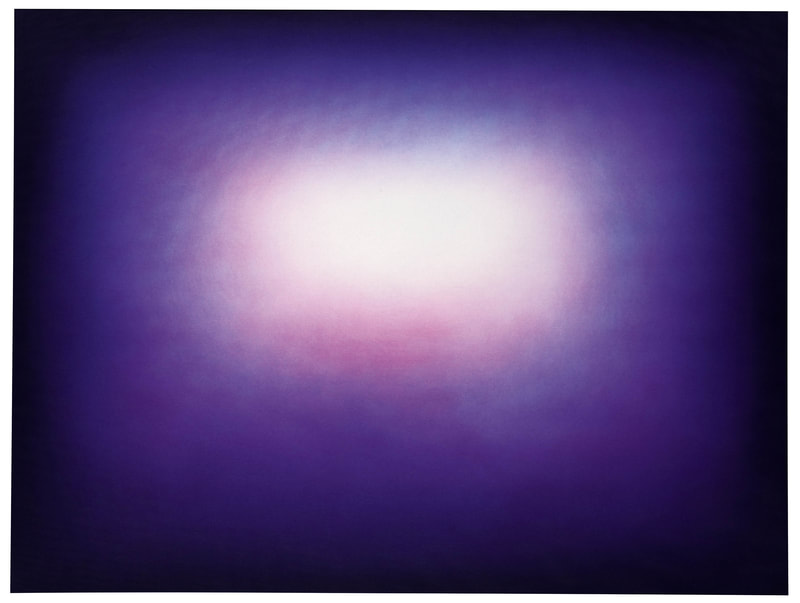

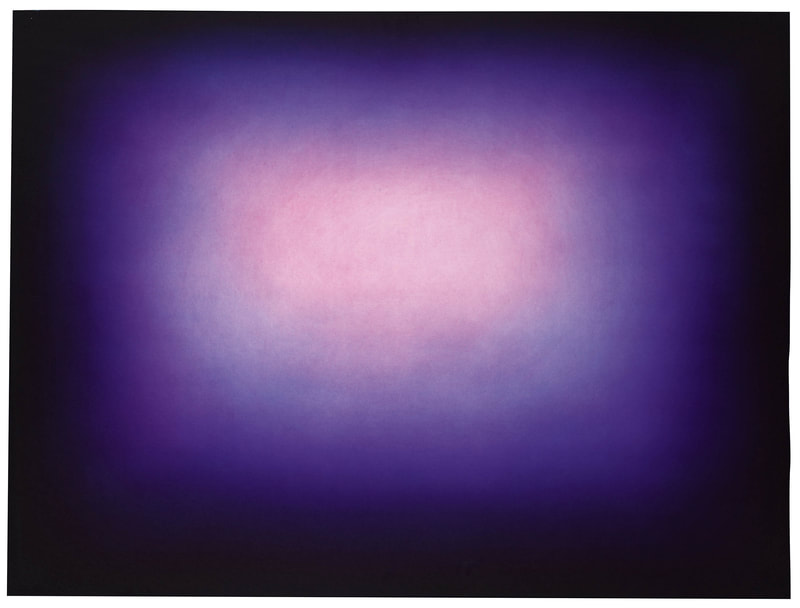

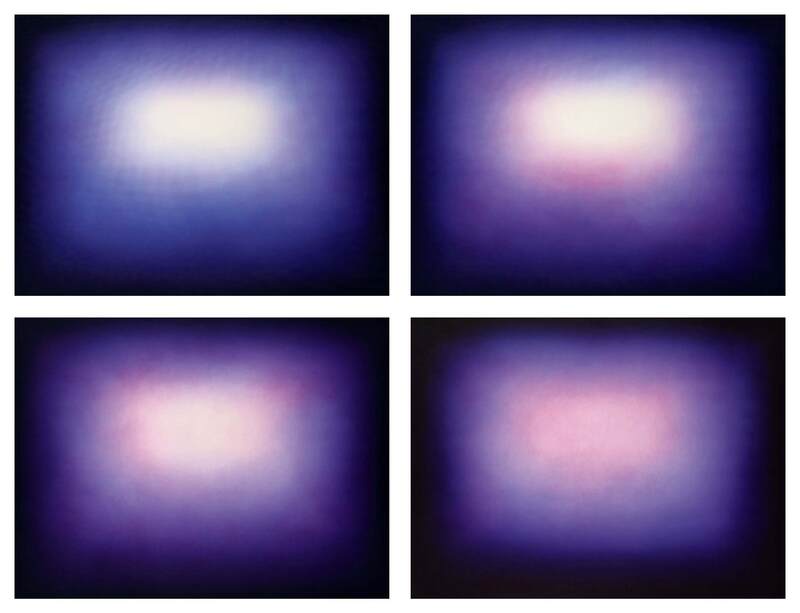

Episode 2 has Ann looking at a set of four polymer gravures by the sculptor Anish Kapoor, which he made at Thumbprint Press for the publisher Paragon Press, London. These are completely abstract images of pure color and are two plates with two colors for each print. The glow from within and ask questions about 2D versus 3D space, voids, and moiré patterns.

The audio link is below. You can also find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, etc. The video version of this episode is on YouTube. Publisher: The Paragon Press Printer: Thumbprint Press Images: copyright Anish Kapoor and Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd. Image credit: Stephen White & Co. Music: Michael Diamond

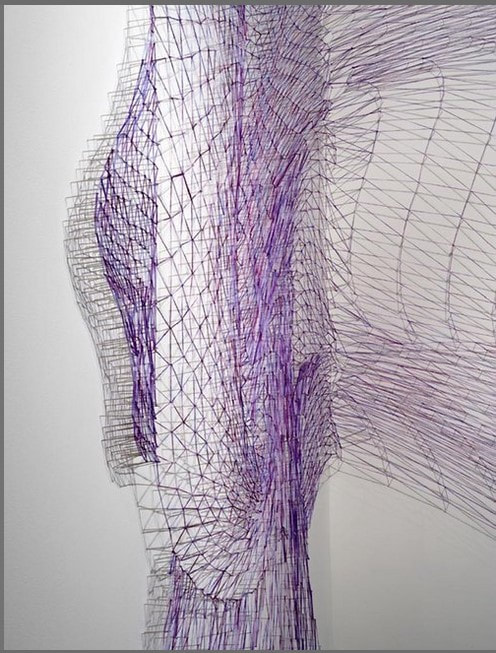

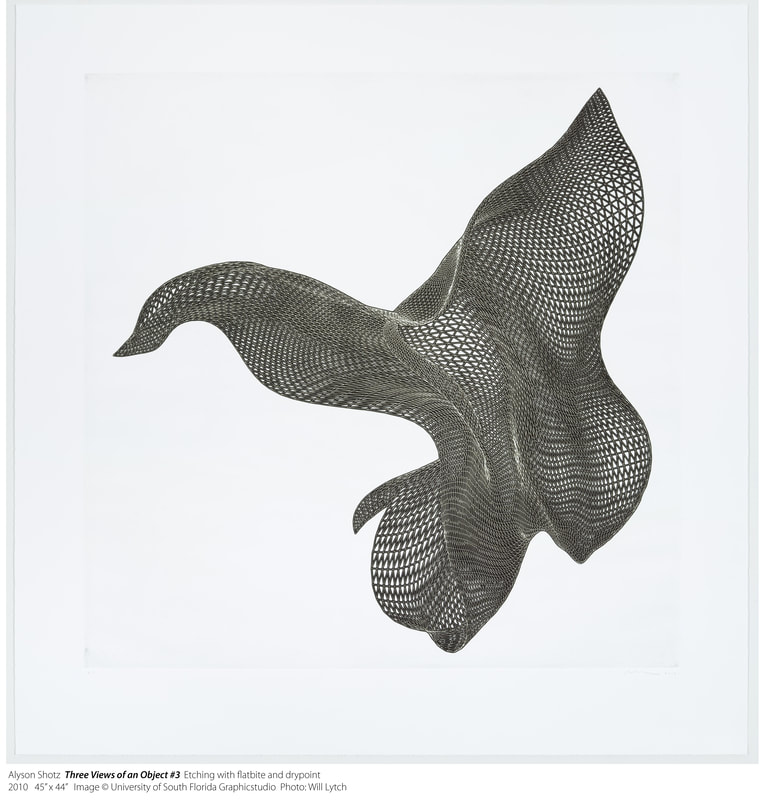

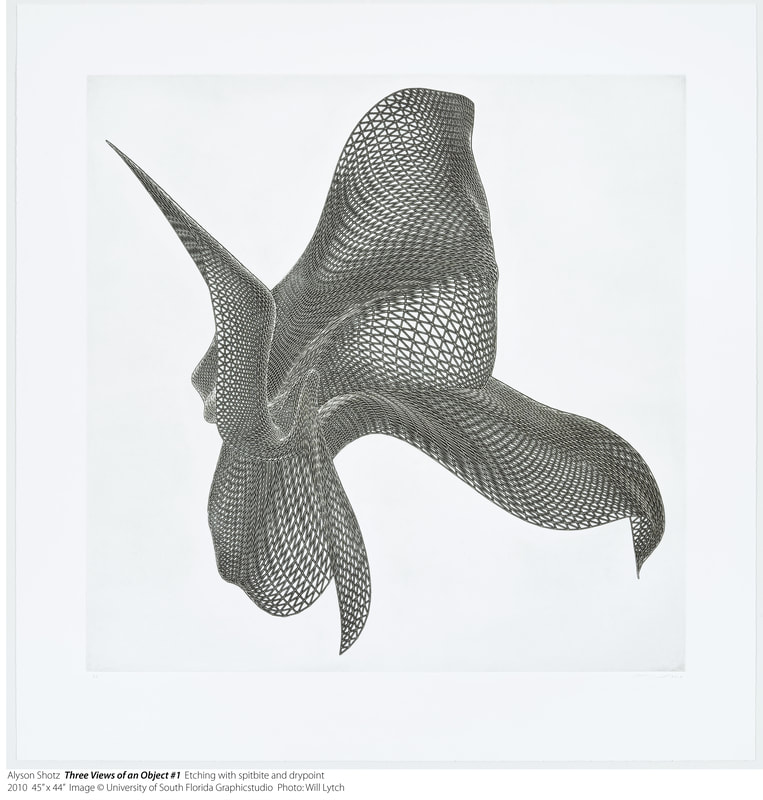

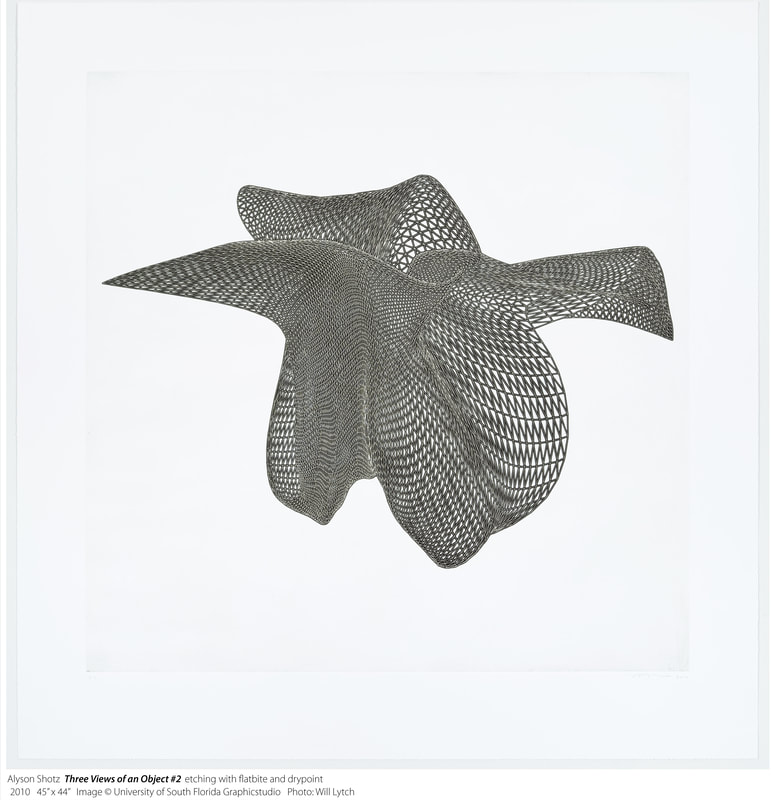

Episode 1 has Ann looking at a set of three photoetchings by the sculptor Alyson Shotz, which she made at Graphicstudio, University of South Florida, Tampa. Ann talks about tripping over them on a gallery walk around Chelsea in 2011, and how they grabbed her immediately. Hear how their digital birth transforms into a very hand-ed etching--a veritable digital analog bridge. But one must look closely. As Ann has often said: these print reward scrutiny.

Introducing The Curator's Choice tagline: Keep looking closely and ye shall be rewarded. There is a video version of the episode available on YouTube

Press purple Play button to listen to audio-only version. ↓

Click Play to watch a video version on YouTube. ↓

|

Ann ShaferHost and resident curator Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed